https://www.epi.org/blog/black-and-brown-workers-saw-the-weakest-wage-gains-over-40-year-period/

Key takeaways:

- Wage growth for typical Black and Hispanic workers fell far short of growth for white workers over the past 40 years.

- Increasing income inequality overall and racial discrimination in the labor market both play a role in limiting wage gains for Black and Hispanic workers.

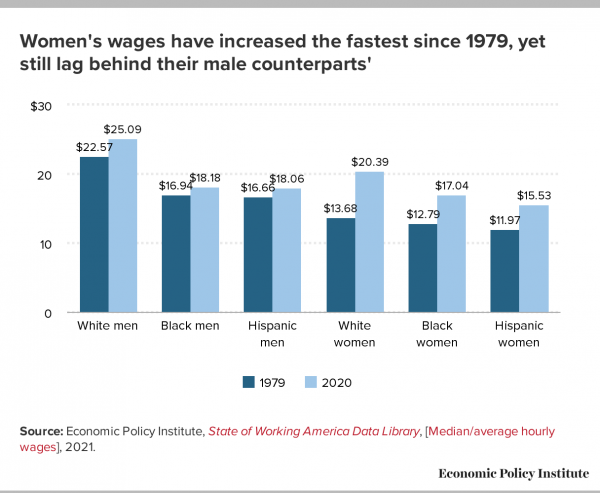

- Women's median wages have increased since 1979 but still lag those of men. Gains among women have not been equally shared, with white women seeing the largest wage increases.

Policy recommendations:

- Create "high-pressure" labor markets by running the economy hot through expansionary macroeconomic policies; prioritizing low unemployment will help spur job growth as well as wage growth, especially for Black workers.

- Prioritize anti-discrimination enforcement.

- Pass the Raise the Wage Act and the Richard L. Trumka PRO Act. These would have a range of positive benefits for workers across the board, and especially for women, Black, and Hispanic workers.

Increasing income inequality has been at the forefront of economic policy conversations in the United States since at least the 2008 financial crisis. The roots of that inequality stretch back much further, though. Growing employer opposition to unions and the shift from manufacturing toward finance as a major growth industry over many decades has resulted in a separation between worker pay and productivity that has persisted to this day.

There has been growing concern about the wage stagnation faced by the typical American worker, and increasing attention paid to the need to rectify this—to ensure that workers reap the gains associated with their increased productivity.

By the numbers

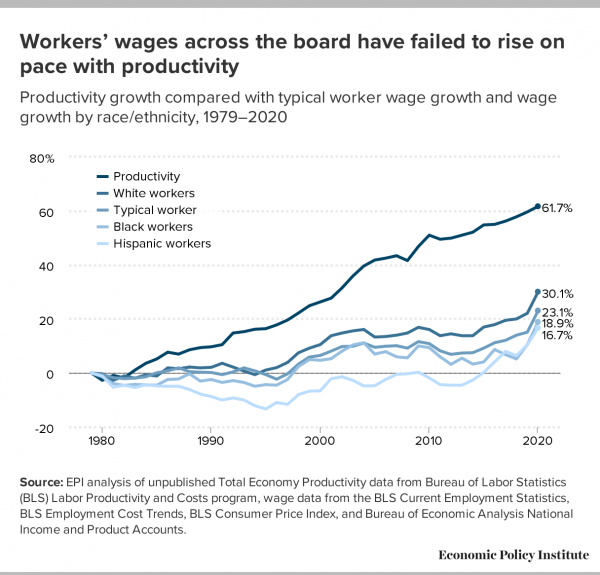

Wage growth by race/ethnicity, 1979–2020

- White workers: 30.1 %

- Black workers: 18.9%

- Hispanic workers: 16.7%

The productivity–pay gap

- Productivity growth, 1979–2020: 61.7%

- Typical worker wage growth, 1979–2020: 23.1%

However, there has not been as much attention paid to the distinct divisions that exist even among the generally undercompensated working class. While the typical worker has not seen their fair share of wage increases relative to the increase in productivity over the past 40 years, Black and Hispanic workers saw even smaller wage gains relative to their white counterparts.

These racial disparities in pay add another dimension to conversations about gaps between pay and productivity, and about income inequality in general. While policies designed to link the typical worker's pay more closely with productivity are necessary to reduce income inequality overall, the persistence of disparities even within the working class shows us that targeted policies will be required in addition if we want to achieve the goal of true equity across the board.

Closing wage gaps for the vast majority of undercompensated workers is not a zero-sum game. The right combination of progressive class-based policies targeting income and wage inequality, alongside anti-discrimination policies targeting race-specific gaps, can have powerful effects on raising all workers' pay.

Key takeaways of this post include:

- The typical worker's wages rose only 23.1% from 1979 to 2020, while productivity increased 61.7%. For Black and Hispanic workers, wage growth was even more dismal, at 18.9% and 16.7%, respectively.

- Skyrocketing income inequality as a whole has mechanically increased measured racial gaps, and clamping down on concentrated redistribution at the top levels of the income bracket will play a large role in raising all workers' pay.

- Given that Black workers face a "double penalty" due to a combination of wage inequality and employer discrimination, policies targeting racial gaps need to be combined with progressive class-based policies.

- Women's median wages have increased since 1979 but still lag behind those of men. Gains among women have not been equally shared, with white women seeing the largest wage increases.

- A powerful multiracial coalition that draws attention to the positive-sum solidarity behind closing the pay–productivity gap can put pressure on policymakers to achieve this long overdue pay raise for the vast majority of U.S. workers.

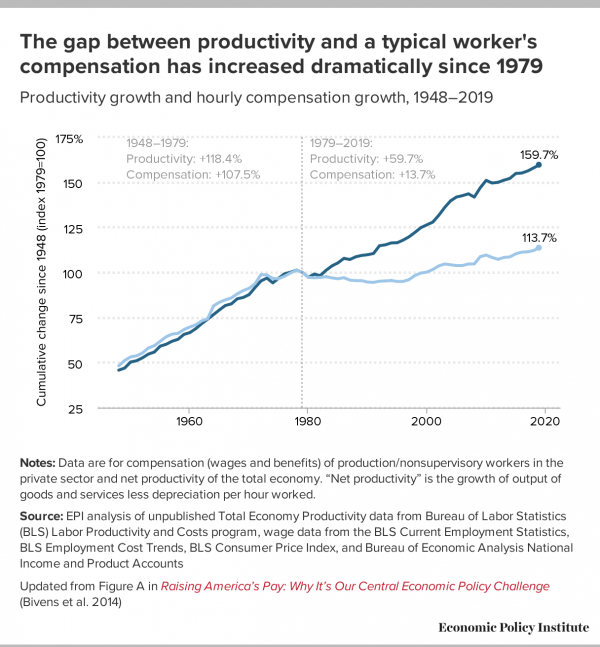

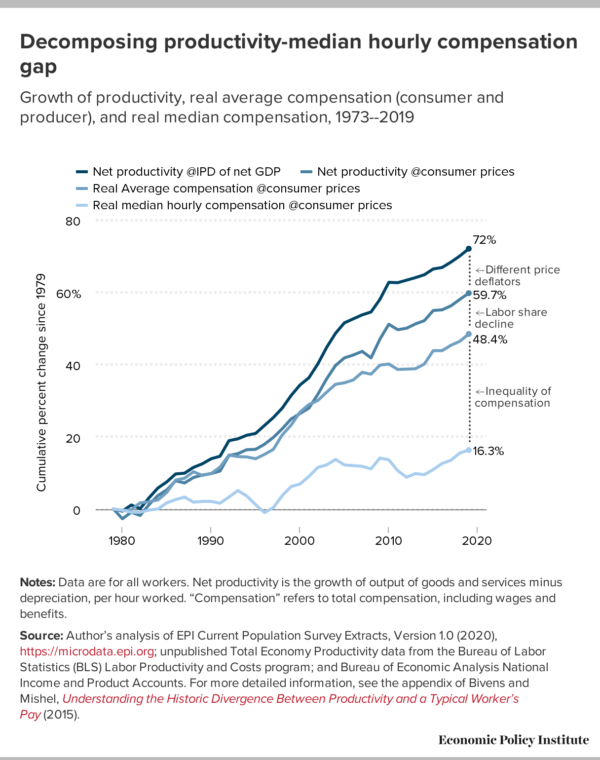

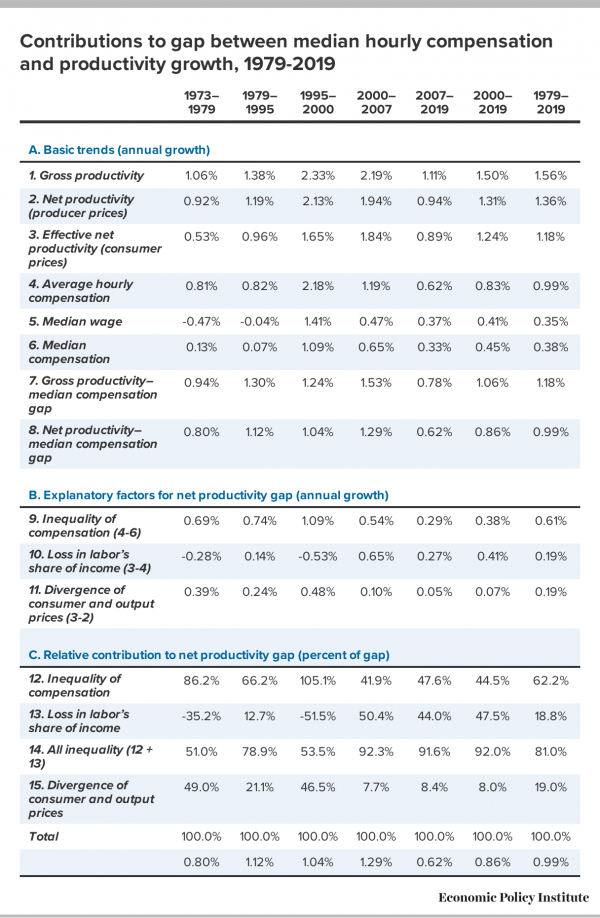

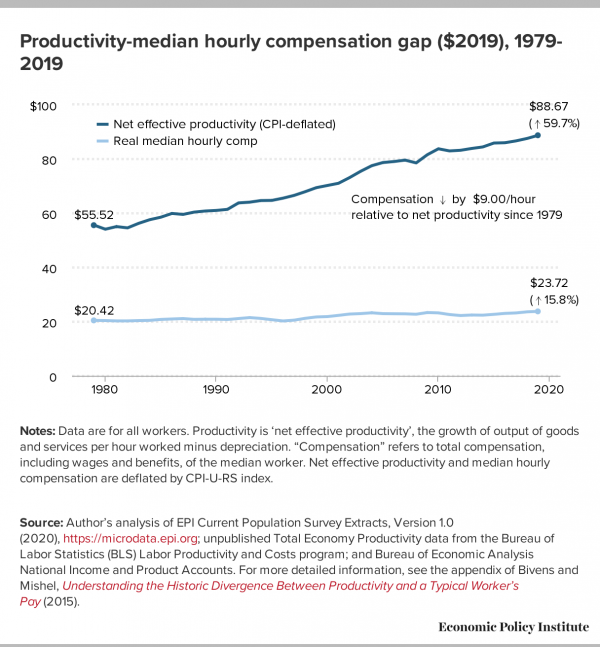

Trends in pay/productivity over the past 40 years

Over the past 40 years, declining union density across the country has coincided with a separation between growth in wages and growth in productivity. This represents a concrete shift in the balance of power between employers and management versus the typical worker. While productivity gains created the potential for pay increases, most wage gains since the 1980s have gone to the highest-paid employees. While worker productivity grew by 61.7% between 1979 and 2020, workers' median wages grew by only 23.1% (Figure A). Meanwhile, CEO pay has skyrocketed compared with the pay received by the typical worker; the ratio of CEO-to-typical-worker compensation was 351-to-1 in 2020, and realized compensation for CEOs grew by 1,322% between 1978 and 2020.

This delinking of pay from productivity has led to an explosion of growth-limiting inequality in the United States; that is, not only has the economic "pie" become less evenly distributed, but it has also grown at a slower pace than it could have grown under a more equal distribution.

This means that a thoughtfully selected set of policy decisions has the potential to both produce faster economic growth and reduce inequality.

Trends in racial wage gaps over the past 40 years

Racial wage disparities are a long-standing feature of the U.S. economy; little progress has been made in reducing gaps since the 1980s, when political opinion turned against affirmative action and other race-specific policy levers. The primary avenue through which discrimination affects racial wage gaps is through occupational segregation; employers tend to sort Black, Hispanic, and white workers into different occupations with differing levels of compensation and potentials for advancement.

Wilson and Rodgers (2016) conclude that, since the 1980s, racial discrimination has played the largest role in widening the gap between Black and white pay. Quillian et al. (2017) find no reduction in the level of racial discrimination in hiring against Black job seekers since 1989. These should not be surprising results, as the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), the federal institution tasked with investigating violations of and enforcing antidiscrimination law, has been severely underfunded for decades. Recent work by Kline et al. (2021) shows that a few large firms in the U.S. economy are prolific discriminators at a systemic level. This suggests that targeted anti-discrimination enforcement may be an effective tool to help reverse this trend.

The rise in income inequality more generally, as well as the separation between the typical worker's pay and productivity, has also influenced racial wage gaps. We know that pay increases have been concentrated at higher income levels over the last 40 years, while lower-income workers have seen much lower wage growth. Since Black and Hispanic workers are disproportionately concentrated in lower-income occupations, this unequal wage growth has fallen more heavily on those workers than on their white counterparts.

As the recovery from the 2008 financial crisis stretched into the longest period without a recession in U.S. history in the late 2010s, the slowly tightening labor market began to produce wage gains for those at the bottom of the income distribution. This is consistent with economic history: Tight labor markets (supported by expansionary monetary policy) have historically been necessary to bring about wage increases for low-income workers and have been crucial in reducing racial gaps in labor market outcomes.

Anomalous wage 'growth' in 2020: The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on wage data

The onset of the coronavirus pandemic and its ensuant recession cut the long expansion abruptly short. In the year after the recession, the effect on the typical worker's wages was counterintuitive, however. Median wages increased across the board during 2020, to a greater degree than in any single year since 1998. In fact, most of the wage gains relative to 1979 for Black and Hispanic workers came in 2020—but not for the reasons one might hope. The wage "growth" on the surface masks the bad news we already knew: Millions of people lost their jobs in 2020, including large numbers of low-wage workers.

Wage growth in the late 1990s and late 2010s was driven by a historically tight labor markets and low interest rates, but job losses drove the spike in 2020. There was a dramatic shift in the composition of jobs being measured, as low-income jobs disappeared to such a degree that the wages left to be measured were mechanically higher.

The service-sector workers hit the hardest by the pandemic and recession were not only those with some of the lowest wages and fewest labor protections, but they were also among those at highest risk for contagion. Given that risk, combined with closures of schools and child care centers, it is not surprising that many workers did not or could not return to their prior jobs when the economy began to reopen.

Meanwhile, those in middle- and high-income occupations were able to convert some or all of their work to remote work much more easily than those in low-income occupations, due both to the inherent nature of the work and the flexibility of work arrangements that comes with having a higher-status job. Therefore the median wage skewed upward toward these middle- and high-income workers.

Real wage raises continue to be long overdue for most workers, which is cause for deep concern. We have yet to see a sustainable increase in bargaining power on behalf of American workers as a result of the pandemic. And without lasting and direct policy changes, any rises in wages workers may have experienced in 2020 are likely to be transitory rather than concrete, permanent increases.

Women's pay and productivity pre- and post-2020

While women have seen more significant wage gains than men, percentage-wise, over the past 40 years, their wages have neither caught up to men's wages (Figure B) nor have they kept pace with the overall increase in economywide productivity. Among white, Black, and Hispanic men and women, Black and Hispanic women had the lowest median wages in both 1979 and 2020.

Moreover, women did not experience wage gains equally over the last 40 years. Among women in all racial/ethnic groups, white women received the largest wage increases across all periods. In fact, the gap between white women's wages and Black and Hispanic women's wages has widened dramatically between 1979 and 2020: In 1979, white women were paid around 6.9% and 14.3% more, respectively, than Black and Hispanic women. By 2020, these gaps had widened to 19.7% and 31.3%.

The 2020 pandemic and recession only exacerbated these disparities, impacting women especially severely. Black, Hispanic, and Asian American/Pacific Islander (AAPI) women have long been overrepresented and underpaid in service and care industries (as are women in general), and these industries were among the hardest hit during the pandemic. Women are also more likely to work in state and local public sectors—including a large number working as educators; these public-sector occupations also faced huge levels of unemployment due to public health closures.

With schools and child care centers closed for in-person services, millions of women also left the workforce to care for their children. The lack of safe and affordable child care made the situation especially untenable for low-income households. Even before the unprecedented 2020 shock, women's wages were lagging their productivity as well as lagging behind men's wages, with Black and Hispanic women facing a triple penalty of rising income inequality alongside racial/ethnic and gender discrimination. Women's pay–productivity gap, and the racial and gender disparities within that gap, will only persist—and may widen—without targeted and deliberate policy interventions.

Inequality restricts the economy's potential for growth, but equity can have benefits across groups

Even in the wake of 40 years of increasing income inequality, in general and with respect to race, we can choose to design economic policy that promotes both equity and economic growth. We can grow a healthier economy by curbing the exorbitant growth of compensation at the top of the earnings ladder and giving workers at lower- and middle-income levels more direct control over their working conditions and pay. When paired with well-enforced anti-discrimination laws and material consequences for those who violate those laws, the potential exists for growth that is equitable across class and racial lines.

There may still be conflict when pursuing a growth path that is racially fair and class conscious. Pursuing equity implies a change in relative position for white workers with respect to Black and Hispanic workers, as well as for men with respect to women workers. There will also be resistance from the most highly paid strata of employees toward a more even distribution across workplaces. The fact remains, however, that our pace of productivity growth provides the means for workers across groups to benefit and for those who have been barred from receiving their fair share to finally do so.

Addressing inequality and racial disparities beyond the pandemic

Moving forward, policymakers cannot settle for a pre-pandemic economic status quo. As we've seen, prior to 2020, the gap between productivity and compensation has been widening dramatically since 1979, with especially strong racial and gender disparities. Without sustained investment in raising wages, compensation, and benefits; improving working conditions; and eliminating labor market discrimination, all workers will continue to see their pay dwindle even as their vital labor boosts the economy. There are several short- and long-term policies and economic strategies to close the pay–productivity disparities:

- Tight labor markets: Running the economy hot with "high-pressure" labor markets through expansionary macroeconomic policies and a prioritization of low unemployment can help spur job growth as well as wage growth, especially for Black workers. Concerns over inflation and overheating should not get in the way of strengthening the economic recovery and making sure all workers are seeing the gains.

- Anti-discrimination enforcement: Persistent labor market discrimination and occupational segregation plays an outsize role in how Black and Hispanic workers experience the labor market and employment. Despite educational attainment or job experience, many Black and Hispanic workers are less likely to be hired for certain jobs than less qualified white peers; this is also true for women workers relative to their male counterparts. Pursuing only race-blind or universal economic policies will miss addressing this insidious and engrained phenomenon. Therefore, anti-discrimination enforcement, such as by the EEOC, is crucial.

- Pro-worker legislation: Immediately passing the Raise the Wage Act and the Richard L. Trumka PRO Act will have a range of positive benefits for the workers who have seen their pay stagnate over decades. Higher wages and stronger access to unionization and collective bargaining can help level the playing field and give working people negotiating power with their employers.

Most workers have seen their wages stagnate even as their productivity has risen. Black workers face a double penalty as the forces of growing inequality and racial discrimination reinforce each other.

Recognizing and rectifying the pay–productivity gap is crucial as we strive toward racial and economic justice for Black and brown workers. Economic recovery in the short term, and equity in the long run, will only be achieved when direct policies target income and wage inequality and are paired with anti-discrimination and other measures to close race-based gaps. Through this class- and race-conscious approach, all workers will receive the benefits of the economic strength and prosperity they have built.

-- via my feedly newsfeed