Sunday, March 31, 2019

Highly recommended: Kim Clausing's is the best defense of globalization and openness I have read in years. And former Obama CEA Chair Jason...

Saturday, March 30, 2019

Teacher strikes blanket the nation as a labor of love meets economic hardships [feedly]

https://www.epi.org/blog/teacher-strikes-blanket-the-nation-as-a-labor-of-love-meets-economic-hardships/

School districts around the country, faced with a historic shortage of teachers, should be scrambling to offer those educators higher pay and better working conditions. That's what the economics of supply and demand would dictate.

Instead, we are seeing a spread of teachers' strikes and protests, with Denver and Oakland among the latest in a series of protest waves spreading from West Virginia to Los Angeles.

The gap between the estimated number of additional teachers needed in U.S. public school classrooms and the number that are available to be hired grew from zero to over 110,000 in just the last few years.

What gives? The lack of reaction from policymakers shaping the education landscape is emblematic of a broader disrespect for teachers as professionals over time. Teachers face a curious social situation—clearly and deeply needed but demonstrably undercompensated and poorly supported at work. The spate of recent strikes suggests conditions have reached a breaking point as teachers are forced to take on second and third jobs to make ends meet, and to spend money out of their own pockets to supply classrooms.

Our new analyses for EPI suggest that breaking point is here. This week, we released the first in a series of reports on the growing teacher shortage and the working conditions and other factors behind it. Our research shows that, when we account for the shrinking share of teachers who hold credentials associated with more effective teaching, especially in high-poverty schools, the teacher shortage is worse than estimated. The reports of the series will also show that low relative pay, tough working conditions, and a lack of supports for teachers aren't isolated problems in a handful of districts but challenges being reported by teachers nationwide. The depth and breadth of the crisis shows that the education industry—i.e., the nation's state and local departments and boards of education—urgently need to rethink how they cultivate, train, recruit, and support teachers.

While teaching has long-required forgoing the additional income that teachers could earn if they pursued other careers with similar educational requirements, that income loss has grown substantially in recent years. As our colleagues Larry Mishel and Sylvia Allegretto have shown, in 1994, the pay gap between public school teachers and their comparably educated peers was negligible: teachers earned only 1.8 percent less in wages. In 2017, the teacher pay gap was 10 times that, 18.7 percent. Even accounting for teacher pensions and other benefits, which are often cited as substantially boosting educators' real compensation, the compensation gap is still large, 11.1 percent in 2017. It should come as little surprise, then, that fewer people are choosing teaching as a career and more teachers are leaving.

That kind of situation is never good news. But at a time when the number of students who need teachers is growing, and when those students are more ethnically, racially, and linguistically diverse than ever before, but also more disadvantaged in terms of poverty, it is extremely bad news. We should all be alarmed at the failure of our school systems and our country as a whole to support educators on the front lines who make it possible for students to thrive.

Teachers who successfully struck in Los Angeles earlier in the year illustrate both the scope and scale of the problem and point to first steps toward alleviating it. In L.A., the teachers rejected the district's initial offer of a raise and held out for smaller class sizes and more counselors, nurses, and librarians—resources that should not be considered "extras," but guaranteed. Their emphasis on conditions in schools as well as pay is a sign both of the sorry state in which teachers try to do hard jobs well, and of the low pay they receive to work in those circumstances. But their victory offers hope.

And more change is coming. The L.A. strike kicked off protests in Denver, Kentucky, Virginia, West Virginia (again), and Oakland. Denver teachers, long unhappy that their salaries are contingent on student test scores, are now speaking up and walking off the job. Kentucky teachers protested a pension bill that would remove teachers from the nominating process for the pension board. In Oakland, soaring housing costs and resources lost due to the spread of charters, motivated teachers' walkouts. These protests build on the momentum of the wave of strikes that started in West Virginia just about a year ago and rapidly spread to Oklahoma, North Carolina, or Arizona. Those strikes shined a much-needed spotlight on some of the lowest wages and toughest working conditions for teachers in the country. But as we learn from teachers in districts in states that are relatively "high-paying" states, like California, even relatively "high-paying" states are far from providing what teachers need.

We hope that the series of papers we will publish in the coming months will boost that spotlight and accelerate the development of solutions. As we grapple as a society with rapidly growing income and wealth disparities, those on the front lines, teachers prominent among them, deserve a central place at the table where policy solutions are discussed.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Wednesday, March 27, 2019

Enlighten Radio:Recovery Radio: The Wake Up Everybody Show

Blog: Enlighten Radio

Post: Recovery Radio: The Wake Up Everybody Show

Link: http://www.enlightenradio.org/2019/03/recovery-radio-wake-up-everybody-show.html

--

Powered by Blogger

https://www.blogger.com/

Monday, March 25, 2019

Gerald Epstein: Is MMT “America First” Economics? [feedly]

https://urpe.wordpress.com/2019/03/20/is-mmt-america-first-economics/

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Tim Taylor: What Did Gutenberg's Printing Press Actually Change? [feedly]

http://conversableeconomist.blogspot.com/2019/03/what-did-gutenbergs-printing-press.html

In a similar spirit, I of course know that the introduction of a printing press with moveable type by to Europe in 1439 by Johannes Gutenberg is often called one of the most important inventions in world history. However, I'm grateful that Jeremiah Dittmar and Skipper Seabold have been checking it out. They have written "Gutenberg's moving type propelled Europe towards the scientific revolution," for the LSE Business Review (March 19, 2019). It's a nice accessible version of the main findings from their research paper, "New Media and Competition: Printing and Europe'sTransformation after Gutenberg" (Centre for Economic Perfomance Discussion Paper No 1600 January 2019). They write:

"Printing was not only a new technology: it also introduced new forms of competition into European society. Most directly, printing was one of the first industries in which production was organised by for-profit capitalist firms. These firms incurred large fixed costs and competed in highly concentrated local markets. Equally fundamentally – and reflecting this industrial organisation – printing transformed competition in the 'market for ideas'. Famously, printing was at the heart of the Protestant Reformation, which breached the religious monopoly of the Catholic Church. But printing's influence on competition among ideas and producers of ideas also propelled Europe towards the scientific revolution.While Gutenberg's press is widely believed to be one of the most important technologies in history, there is very little evidence on how printing influenced the price of books, labour markets and the production of knowledge – and no research has considered how the economics of printing influenced the use of the technology."

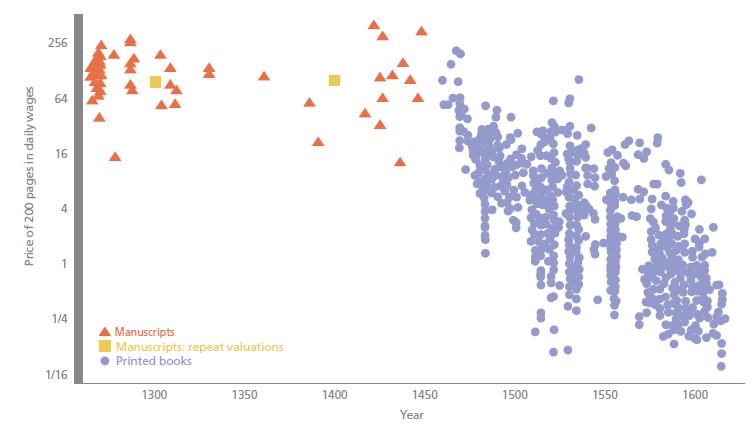

Dittmar and Seabold aim to provide some of this evidence. For example, here's their data on how the price of 200 pages changed over time, measured in terms of daily wages. (Notice that the left-hand axis is a logarithmic graph.) The price of a book went from weeks of daily wages to much less than one day of daily wages.

They write: "Following the introduction of printing, book prices fell steadily. The raw price of books fell by 2.4 per cent a year for over a hundred years after Gutenberg. Taking account of differences in content and the physical characteristics of books, such as formatting, illustrations and the use of multiple ink colours, prices fell by 1.7 per cent a year. ... [I]n places where there was an increase in competition among printers, prices fell swiftly and dramatically. We find that when an additional printing firm entered a given city market, book prices there fell by 25%. The price declines associated with shifting from monopoly to having multiple firms in a market was even larger. Price competition drove printers to compete on non-price dimensions, notably on product differentiation. This had implications for the spread of ideas."

Another part of this change was that books were produced for ordinary people in the language they spoke, not just in Latin. Another part was that wages for professors at universities rose relative to the average worker, and the curriculum of universities shifted toward the scientific subjects of the time like "anatomy, astronomy, medicine and natural philosophy," rather than theology and law.

The ability to print books affected religious debates as well, like the spread of Protestant ideas after Martin Luther circulated his 95 theses criticizing the Catholic Church in 1517.

Printing also affected the spread of technology and business.

Previous economic research has studied the extensive margin of technology diffusion, comparing the development of cities that did and did not have printing in the late 1400s ... Printing provided a new channel for the diffusion of knowledge about business practices. The first mathematics texts printed in Europe were 'commercial arithmetics', which provided instruction for merchants. With printing, a business education literature emerged that lowered the costs of knowledge for merchants. The key innovations involved applied mathematics, accounting techniques and cashless payments systems.It is impossible to avoid wondering if economic historians in 50 or 100 years will be looking back on the spread of internet technology, and how it affected patterns of technology diffusion, human capital, and social beliefs--and how differing levels of competition in the market may affect these outcomes.

The evidence on printing suggests that, indeed, these ideas were associated with significant differences in local economic dynamism and reflected the industrial structure of printing itself. Where competition in the specialist business education press increased, these books became suddenly more widely available and in the historical record, we observe more people making notable achievements in broadly bourgeois careers.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Shaun Ferguson (Triple Crisis): Greening the New Deal [feedly]

http://triplecrisis.com/greening-the-new-deal/

The Green New Deal is desperately needed, and arguing about a price tag is like Henry Ford wondering if the country will be able to afford his brand new automobile. With the introduction of a House Resolution by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-New York) and Sen. Edward Markey (D-Massachusetts), a debate has surged across the country on the affordability of the Green New Deal. The sheer distraction of the affordability discussion is enough to ensure that very few people will pay attention to what is really at stake. For when the bigger fish eat up this little fish we will need to remember how we got here and what matters most. As the bright young critics have quickly observed, the Green New Deal could hardly be too green. Time is wearing thin and we need to make haste.

But there can be no greening that abstracts from political economy realities and while the tug of war taking place in the media at the moment is all about the so-called economy-of-it-all, there is next to no analysis on the political constraints of sustainably embarking on another New Deal when the first one withered away long ago. After World War II, the ambition of a nationwide spending program was quickly replicated on an international scale as the country rightly observed that in a vacuum the United States would be hard pressed to expand its economy and that what it needed to make large projects like the Tennessee Valley Authority which introduced unprecedented stimulus, sustainable in the long run was the integration of the United States capital stock's capacity to produce output with a global trend of expanding markets. Unless the United States comes to terms with the global characteristics of its (not to mention everyone else's) economy, we will all the rest of us more than likely pay the brunt of another American adventure. How does America exact these payments? By imposing continued low growth trajectories, low wage growth, contractionary balance of payments adjustments, and what Keynes called "forced exports", which is basically what we call today narrow and specialized development: all opposed to diversification.

If the truth be told, the heavy handed unilateral approach of the United States renders the rest of the global economy akin to something that can be thrown off the back of a train to pay for America's projects. By America's choice, the world has pursued a most exclusionary development path with low growth trajectories being imposed on much of the world's population, even Europe's, to ensure the political dominance of one country, which itself is willing to sacrifice the high growth it could enjoy itself along with the rest of the world through inclusive multilateralism. The decision for this can be traced back to 1951, two years after what has sometimes been referred to as 'the Kaldor Report' was discussed at ECOSOC. This would be the last serious consideration for institutionalizing Full Employment at the international level, which is to say that it was the last serious effort to institutionalize multilateral trading in support of an expansive global economy.

It is this author's opinion that this would have required the mediatory institutions sought by John Maynard Keynes. As he confided to his compatriots, "the difficulties are thoroughly shirked" (Keynes, 1980: 325), "The two Institutions have become different from what we were expecting." (Ibid: 232) These statements commence a long line of lament by those working in the official institutions of international development. Contrary to the less than exhaustive investigations by the most powerful parties involved in the post-War framing, certain extensive and earnest treatments of the rationale for full employment have been attempted. The tensions that constituted the political sequence which framed the post-War economic institutions were all but resolved. They can fruitfully be resubmitted to thought.

The ability of the USA to pay for the Green New Deal is inherently connected to its relation to the global economy, at the broadest level. It can flounder on uninviting seas and when needed release its fury spanking the waves after Xerxes, or it can take stock of what Keynes called the "high ways of the real world", and awake to the rough realities it has imposed around the globe. To the extent that America's low growth trajectory displaces demand in the global economy— or to the extent that its low wage growth policy is the only way it manages to insert itself into the global economy, its longstanding policy of aggressive bilateralism will continue. The world's economies are intimately interlinked and what is needed is not an American scheme but a global one — which picks up the multilateralism that once wanted to be born.

Shaun Ferguson has worked in development economics at various United Nations agencies including UNCTAD, ESCWA and UNSCO since 2002. He has a doctoral degree in Economics at the New School for Social Research.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Raising the Curtain: Trade and Empire [feedly]

My take: Trade and imperialism -- is not their ultimate legacy a global society? and thus, internationalism shall finally, and inevitably rise as the true humanism. The goods and bads are intertwined.

https://www.bradford-delong.com/2019/03/raising-the-curtain-the-long-twentieth-centurytrade-and-empire-yet-another-outtake-from-slouching-towards-utopia-an-e.html

Raising the Curtain: The Long Twentieth Century—Trade and Empire

The extent to which the navies and trading fleets of the great European sea-borne empires of the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries shaped the industrial development of western Europe has always been one of the most fiercely-debated and unsettled topics in economic history. That European expansion in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries were catastrophes for the regions of west Africa that were the sources of the slave trade; for the Amerindians of the Caribbean; for the Aztecs, Incas, the mound-builders of the Mississippi valley; and for the princes of Bengal and others who found themselves competing with the British East India Company in the succession wars over the spoils of India's Moghul Empire—that is not in dispute.

But how much did pre-industrial trade and plunder affect European development? That is not so clear.

It is clear is that even at the end of the eighteenth and the first half of the nineteenth century trade not in luxuries but in staples had begun to profoundly shape history. For the first time transoceanic trade mattered not just for a ruling elite but for an economy as a whole. The export of cotton from the American South and had mattered. Without the appetite of British and New England factories for cotton and the power to ship ginned cotton to them cheaply, the slaves of the American South in 1860 would have been what they were for George Washington in the 1790s: a quarter of your wealth that you were willing to free, at least upon your death, because it was the right thing to do. By contrast, for Jefferson Davis it wasn't his land but rather his slaves that were three-quarters of his wealth—and so the U.S. Civil War of 1861-5 came.

Early-nineteenth century cotton showed what late-eighteenth century sugar had prefigured. The export of sugar from the Caribbean islands and Latin America (and also tobacco, tea, coffee, chocolate, and so forth) meant that European agriculture did not have to grow nearly as much flax or raise as much wool or produce as many calories. It provided an extra edge to the British economy: as if there was perhaps one additional ghost worker who did not have to be fed or paid alongside every ten.

That, from the perspective of 1870, was what the expanded intercontinental division of labor and the higher productivity that resulted from it had done up to that point.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Friday, March 22, 2019

Reentry from Out of the Labor Market [feedly]

https://conversableeconomist.blogspot.com/2019/03/reentry-from-out-of-labor-market.html

Here, I'll focus on some pieces of the 2019 Economic Report of the President that focus more on underlying economic patterns, rather than on policy advocacy. For example, some interesting patterns have emerged in what it means to be "out of the labor market."

Economists have an ongoing problem when looking at unemployment. Some people don't have a job and are actively looking for one. They are counted as "unemployed." Some people don't have a job and aren't looking for one. They are not included in the officially "unemployed," but instead are "out of the labor force." In some cases, those who are not looking for a job are really not looking--like someone who has firmly entered retirement. But in other cases, some of those not looking for a job might still take one, if a job was on offer.

This issue came up a lot in the years after the Great Recession. The official unemployment rate topped out in October 2009 at 10%. But as the unemployment rate gradually declined, the "labor force participation" rate also fell--which means that the share of Americans who were out of the labor force and not looking for a job was rising.You can see this pattern in the blue line below.

There were some natural reasons for the labor force participation rate to start declining after about 2010. In particular, the leading edge of the "baby boom" generation, which started in 1945, turned 65 in 2010, so it had long been expected that labor force participation rates would start falling with their retirements.

Notice that the fall in labor force participation rates levelled off late in 2013. Lower unemployment rates since that time cannot be due to declining labor force participation. Or an alternative way to look at the labor market is to focus on employment-to-population--that is, just ignore the issue of whether those who lack jobs are looking for work (and thus "in the labor force") or not looking for work (and thus "out of the labor force"). At about the same time in 2013 when the drop in the labor force participation rate leveled out, the red line shows that the employment-to-population ratio started rising.

What especially interesting is that many of those taking jobs in the last few years were not being counted as among the "unemployed." Instead, they were in that category of "out of the labor force"--that is, without a job but not looking for work. However, as jobs became more available, they have proved willing to take jobs. Here's a graph showing the share of adults starting work who were previously "out of the labor force" rather than officially "unemployed."

A couple of things are striking about this figure.

1) Going back more than 25 years, it's consistently true that more than half of those starting work were not counted as "unemployed," but instead were "out of the labor force." In other words, the number of officially "unemployed" is not a great measure of the number of people actually willing to work, if a suitable job is available.

2) The ratio is at its highest level since the start of this data in 1990. Presumably this is because when the official unemployment rate is so low (4% or less since March 2018), firms that want to hire are needing to go after those who the official labor market statistics treated as "not in the labor force."

-- via my feedly newsfeed

For ACA’s 9th Anniversary, CBPP Examines Options to Further Expand Coverage [feedly]

https://www.cbpp.org/blog/for-acas-9th-anniversary-cbpp-examines-options-to-further-expand-coverage

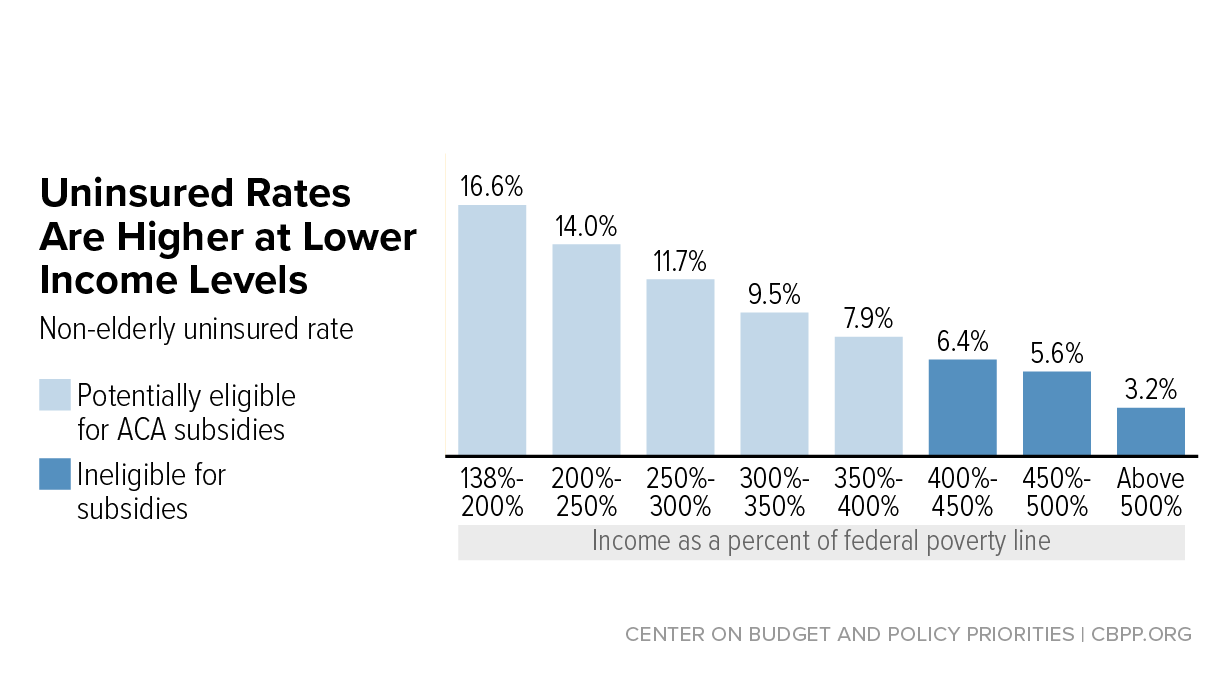

Nine years after President Obama signed the Affordable Care Act (ACA) on March 23, 2010, the uninsured rate remains at a historic low and more than 20 million people have gained coverage — but about 30 million non-elderly people are still uninsured. Several new CBPP analyses examine the uninsured and identify policies to continue expanding coverage and making coverage and health care more affordable.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Thursday, March 21, 2019

Tim Taylor: Wealth, Consumption, and Income: Patterns Since 1950 [feedly]

http://conversableeconomist.blogspot.com/2019/03/wealth-consumption-and-income-patterns.html\\ Many of us who watch the economy are slaves to what's changing in the relatively short-term, but it can be useful to anchor oneself in patterns over longer periods. Here's a graph from the 2019 Economic Report of the Presidentwhich relates wealth and consumption to levels of disposable income over time.

The red line shows that total wealth has typically equal to about six years of total personal income in the US economy: a little lower in the 1970s, and a little higher in recent years at the peak of the dot-com boom in the late 1990s, the housing boom around 2006, and the present.

The blue line shows that total consumption is typically equal to about .9 of total personal income, although it was up to about .95 before the Great Recession, and still looks a shade higher than was typical from the 1950s through the 1980s.

Total stock market wealth and total housing wealth were each typically roughly equal to disposable income from the 1950s up through the mid-1990s, although stock market wealth was higher in the 1960s and housing wealth was higher in the 1980s. Housing wealth is now at about that same long-run average, roughly equal to disposable income. However, stock market wealth has been nudging up toward being twice as high as total disposable income in the late 1990s, round 2007, and at present .

A figure like this one runs some danger of exaggerating the stability of the economy. Even small movements in these lines over a year or a few years represent big changes for many households.

What jumps out at me is the rise in long-term stock market wealth relative to income since the late 1990s. That's what is driving total wealth above its long-run average. And it's probably part of what what is causing consumption levels relative to income to be higher as well. That relatively higher level of stock market wealth is propping up a lot of retirement accounts for both current and future retirees--including my own.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Dean Baker: Paying for a Green New Deal with Modern Monetary Theory [feedly]

http://cepr.net/publications/op-eds-columns/paying-for-a-green-new-deal-with-modern-monetary-theory

Dean Baker

The Hankyoreh, March 17, 2019

Much of the Democratic Party, including almost the entire pack of contenders for the Democratic presidential nomination, has embraced the concept of a Green New Deal (GND). This is an ambitious plan for slashing greenhouse gas emissions, while at the same time creating good-paying jobs, improving education, and reducing inequality.

At this point, the specific policies entailed by these ambitious goals are largely up for grabs, as is the question of how to pay for this agenda. One way of paying for it, borrowing from the economic doctrine know as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), is that we don't have to.

Modern Monetary Theory argues that a government that prints its own currency is not constrained in its spending by its tax revenue. Some on the left have argued that we can just print whatever money we need to finance a GND. This claim does not make sense.

The logic of MMT's claim is that, since the US government prints its own currency, it is not constrained by revenue from taxes, or what it borrows in credit markets. It can always just print the money it needs to cover its spending.

If the government wants to spend another billion dollars paying workers to build roads or paying contractors for steel, who is going to turn down its money? They will just be happy to get the money, end of story.

The limiting factor is that, at some point, this process can lead to inflation. If an economy has a substantial amount of excess capacity, meaning that there are a large number of unemployed workers and idle factories and other facilities, the additional spending due to printing money will just put some workers and factories to use. There should still be plenty of competitive pressure to limit wage and price increases.

This was quite effectively demonstrated in the recovery from the Great Recession, in which the United States, the eurozone, and Japan have all struggled to increase their rates of inflation. In all three cases, the large-scale printing of money had a modest impact, at best, in raising the rate of inflation. The predictions of runaway inflation made by conservative economists were shown to be completely wrong.

While it's true that countries could print money to boost their economies to recover from the Great Recession, that doesn't mean that the United States could now spend a large amount of money on GND projects, without tax increases and/or offsetting spending cuts. The reason is that we have largely recovered from the Great Recession.

The unemployment rate is now under 4.0 percent, lower than it was before the Great Recession started. While there is some evidence of slack in the labor market by various measures, it has tightened to the point that workers are now seeing pay increases that exceed the rate of inflation.

The average hourly wage increased by 3.2 percent over the last year. That compares to a 2.8 percent rate of increase in the prior year, and a 2.4 percent increase from 2016 to 2017. This tightening of the labor market is great news because it means that millions more workers have jobs and that most workers are now sharing in the gains from growth.

However, it means that we are pretty much at the end of the "just print money" option. If we were to spend an additional $200 billion a year (1.0 percent of GDP) on installing solar panels and windmills, retrofitting buildings, and building electric cars and buses, it would further increase demand in the labor market and almost certainly lead to considerably more rapid wage growth.

While slightly faster wage growth would be fine, this sort of boost to demand is likely to quickly push the rate of wage growth to well over 4.0 percent or even 5.0 percent. Higher wages could come partly out of profits (there was an enormous shift from wages to profits in the Great Recession, which could be reversed), but pretty soon, substantially more rapid wage growth would be passed on in prices.

We would then be getting the story that the conservative economists had always warned about, with printing money leading to inflation. How high inflation goes would depend on how far we go down the just print money route.

All of our models show that inflation is a gradual process, with more rapid price increases leading workers to demand higher wages, which are then passed on in another round of price increases.

It's hard to say with any certainty how fast this inflation would accelerate since we haven't really had much of a problem with inflation since the 1970s, almost 40 years ago. The world is a very different place today, with the US having a much more open economy and unions being far less powerful.

Still, there is little reason to question that the standard economic logic will still apply. If we have a very tight labor market where employers are competing for workers by bidding up wages, this will lead to upward pressure on prices, which will cause workers to demand higher wages to maintain their standard of living.

MMT does not give us a way around this picture. While it was important to point out that we didn't have to worry about deficits in the downturn, telling us that we can just print money as the economy nears full employment does not make sense. If we want to have a big GND, we will have to find some ways to pay for it.

We should perhaps not blame politicians who advocate a GND without telling us how they plan to pay for it. After all, Republican politicians have been getting elected for 40 years by promising big tax cuts without saying how they would pay for them. It is understandable that Democrats might think that they should also be able to promise now and pay later.

But, if they tell us that we don't have to pay for it, they are wrong. The printing press will not do the trick.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Tuesday, March 19, 2019

Yanos V: Stagnant Capitalism [feedly]

https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/capitalism-natural-tendency-toward-stagnation-by-yanis-varoufakis-2019-03

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Today, a long decade after the 2008 global financial crisis, this touching faith once again lies in tatters as capitalism's natural tendency toward stagnation reasserts itself. The rise of the racist right, the fragmentation of the political center, and mounting geopolitical tensions are mere symptoms of capitalism's miasma.

A balanced capitalist economy requires a magic number, in the form of the prevailing real (inflation-adjusted) interest rate. It is magic because it must kill two very different birds, flying in two very different skies, with a single stone. First, it must balance employers' demand for waged labor with the available labor supply. Second, it must equalize savings and investment. If the prevailing real interest rate fails to balance the labor market, we end up with unemployment, precariousness, wasted human potential, and poverty. If it fails to bring investment up to the level of savings, deflation sets in and feeds back into even lower investment.

It takes a heroic disposition to assume that this magic number exists or that, even if it does, our collective endeavors will result in an actual real interest rate close to it. How do free marketeers convince themselves that there exists a single real interest rate (say, 2%) that would inspire investors to funnel all existing savings into productive investments and spur employers to hire everyone who wishes to work at the prevailing wage?

Faith in capitalism's capacity to generate this magic number stems from a truism. Milton Friedman liked to say that if a commodity is not scarce, then it has no value and its price must be zero. Thus, if its price is not zero, it must be scarce and, therefore, there must be a price at which no units of that commodity will be left unsold. Similarly, if the prevailing wage is not zero, all those who want to work for that wage will find a job.

Applying the same logic to savings, to the extent that money can fund the production of machines that will produce valuable gadgets, there must be a low enough interest rate at which someone will borrow all available savings profitably to build these machines. By definition, concluded Friedman, the real interest rate settles down, quite automatically, to the magic level that eliminates both unemployment and excess savings.

If that were true, capitalism would never stagnate – unless a meddling government or self-seeking trade union damaged its dazzling machinery. Of course, it is not true, for three reasons. First, the magic number does not exist. Second, even if it did, there is no mechanism that would help the real interest rate converge toward it. And, third, capitalism has a natural tendency to usurp markets via the strengthening of what John Kenneth Galbraith called the cartel-like managerial "technostructure."

Europe's current situation demonstrates amply the non-existence of the magical real interest rate. The EU's financial system is holding up to €3 trillion ($3.4 trillion) of savings that refuse to be invested productively, even though the European Central Bank's deposit interest rate is -0.4%. Meanwhile, the European Union's current-account surplus in 2018 amounted to a gargantuan $450 billion. For the euro's exchange rate to weaken enough to eliminate the current-account surplus, while also clearing the savings glut, the ECB's interest rate must fall to at least -5%, a number that would destroy Europe's banks and pension funds in the blink of an eye.

Setting aside the magical interest rate's non-existence, capitalism's natural tendency to stagnation also reflects the failure of money markets to adjust. Free marketeers assume that all prices magically adjust until they reflect commodities' relative scarcity. In reality, they do not. When investors learn that the Federal Reserve or the ECB is thinking of reversing its earlier intention to increase interest rates, they worry that the decision reflects a gloomy outlook regarding overall demand. So, rather than boosting investment, they reduce it.

Instead of investing, they embark on more mergers and acquisitions, which strengthen the technostucture's capacity to fix prices, lower wages, and spend their cash buying up their companies' own shares to boost their bonuses. Consequently, excess savings increase further and prices fail to reflect relative scarcity or, to be more precise, the only scarcity that prices, wages, and interest rates end up reflecting is the scarcity of aggregate demand for goods, labor, and savings.

What is remarkable is how unaffected free marketeers are by the facts. When their dogmas crash on the shoals of reality, they weaponize the epithet "natural." In the 1970s, they predicted that unemployment would disappear if inflation were subdued. When, in the 1980s, unemployment remained stubbornly high despite low inflation, they proclaimed that whatever unemployment rate prevailed must have been "natural."

Similarly, today's free marketeers attribute the failure of inflation to rise, despite wage growth and low unemployment, to a new normal – a new "natural" inflation rate. With their Panglossian blinders, whatever they observe is assumed to be the most natural outcome in the most natural of all possible economic systems.

But capitalism has only one natural tendency: stagnation. Like all tendencies, it is possible to overcome by means of stimuli. One is exuberant financialization, which produces tremendous medium-term growth at the expense of long-term heartache. The other is the more sustainable tonic injected and managed by a surplus-recycling political mechanism, such as during the WWII-era economy or its postwar extension, the Bretton Woods system. But at a time when politics is as broken as financialization, the world has never needed a post-capitalist vision more. Perhaps the greatest contribution of the automation that currently adds to our stagnation woes will be to inspire such a vision.

The Dangerous Absurdity of America’s Trade Wars [feedly]

https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/trump-dangerous-absurd-trade-wars-by-jeffrey-d-sachs-2019-03

EW YORK – Don Quixote fought windmills. US President Donald Trump fights trade deficits. Both battles are absurd, but at least Quixote's was tinged with idealism. Trump's is drenched in enraged ignorance.

RENEWING EUROPE

Mar 4, 2019 EMMANUEL MACRONcalls on EU citizens to focus on three goals ahead of the critical European Parliament election in May.

92Add to BookmarksLast week, it was announced that the US international deficit on goods and services had widened to $621 billion, despite Trump's promise that tough trade policies vis-à-vis Canada and Mexico, Europe, and China would slash the deficit. Trump believes the US trade deficit reflects unfair practices by America's counterparts. He has vowed to end those unfair practices and negotiate fairer trade agreements with those countries.

Yet America's trade deficit is not an indicator of unfair practices by others, and Trump's negotiations will not reverse its growth. The deficit is, instead, a measure of macroeconomic imbalance, one that Trump's own policies – especially the 2017 tax cut – have exacerbated. Its persistence – indeed, its widening – was wholly predictable by anyone who has gotten to the second week of an undergraduate course on international macroeconomics.

Consider an individual who earns income X and spends Y. If we consider the individual's earnings her "exports" of goods and services, and the spending her "imports" of goods and services, it is immediately clear that she runs a surplus of exports over imports if her income is greater than her spending. A deficit means that she spends more than she earns.

The same is true when one adds incomes and spending across an economy, including both the private and public sectors. An economy runs a surplus on its current account (the broadest measure of its international balance) when gross national income (GNI) exceeds domestic spending, and a deficit when domestic spending exceeds GNI. Economists use the term "domestic absorption" for total spending, summing both domestic consumption and domestic investment spending. The current account may then be defined as the balance of GNI and domestic absorption.

It is important to note that the excess of income over consumption is the same as domestic saving. Therefore, the excess of income over absorption may be stated equivalently as the excess of domestic saving over domestic investment. When an economy saves more than it invests, it runs a current-account surplus; when it saves less than it invests, it runs a current-account deficit.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

For a limited time only, get unlimited access to On Point, The Big Picture, and the PS Archive, plus our annual magazine, for less than $2 a week.

SUBSCRIBE

Notice that trade policy is missing from the entire equation. A deficit on the current account is purely a macroeconomic measure: the shortfall of saving relative to investment. The US external deficit is not in any way, shape, or form an indicator of unfair trade practices by Canada and Mexico, the European Union, or China.

Trump thinks it is because he is ignorant. And his ignorance holds center stage in US public discourse mainly because of the pusillanimity of Trump's advisers (who, admittedly, lose their jobs when they cross him), the Republican Party, and American CEOs (who refuse to reject Trump's nonsense).

The US moved from current-account surpluses to chronic deficits beginning in the 1980s, mainly as the result of a series of tax cuts under Presidents Ronald Reagan, George W. Bush, and Trump. Cuts in taxes not matched by cuts in government consumption reduce government saving. A fall in government saving may be partly offset by a rise in private saving – for example, when businesses and households regard the tax cuts as temporary. Yet such an offset will generally be incomplete. Tax cuts therefore tend to reduce domestic saving, which in turn pushes the current account deeper into deficit.

Data from the Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis show that in the 1970s, US government saving averaged -0.1% of GNI, while private saving averaged 22.2% of GNI. Domestic saving was therefore 22.1% of GNI. In the first three quarters of 2018, US government saving was -3.1% of GNI, while private saving was 21.8% of GNI, so that domestic saving was 18.7% of GNI. In turn, the US current-account balance went from a small surplus of 0.2% of GNI in the 1970s to a deficit of 2.4% of GNI in the first three quarters of 2018.

As a result of the 2017 US tax cuts, government saving is likely to fall by around 1% of GNI. Private saving may rise by perhaps half of that, in anticipation of tax increases ahead, with a marginal increase in business investment and declining housing investment producing a modest overall effect. The net result is therefore likely be a rise in the current-account deficit, perhaps of around 0.5% of GNI.

Trump's own signature tax policy is therefore the main explanation of the modest rise in the international imbalance. Again, trade policy is largely irrelevant to the outcome.

Yet trade policy is certainly not irrelevant to the global economy. Far from it. As Trump chases a chimera, the world economy has become more unstable, and relations between the US and most of the rest of the world have palpably worsened. Trump himself is held in disdain in most places, and respect for US leadership has plummeted worldwide.

Of course, Trump's trade policies not only seek to improve America's external balance, but also represent a misguided attempt to contain China and even to weaken Europe. This objective reflects a neoconservative worldview in which national security reflects a zero-sum struggle among nation-states. The economic successes of America's competitors are deemed to be threats to American global primacy, and thus to American security.

These views reflect the strands of belligerence and paranoia that have long been a feature of American politics. They are an invitation to unending international conflict, and Trump and his enablers are giving them free rein. Seen in this context, Trump's misconceived trade wars are nearly as predictable as the macroeconomic imbalances they have so spectacularly failed to address.

-- via my feedly newsfeed