Before war ravaged Yemen, Walid Al-Ahdal did not worry about feeding his children. At his hometown near the Red Sea, his family grew corn, raised goats and relied on their own cow for milk.

But for the last four years, after fighting forced them to flee, their home has been a tent at a camp with 9,000 other families outside the capital city of Sana. Mr. Al-Ahdal has struggled to buy adequate food with his wages as a janitor at a hospital.

Now another war — this one more than 2,000 miles away — has upended their lives again. Food prices are soaring. Since Russia invaded Ukraine, the cost of wheat has more than doubled, while milk has climbed by two-thirds.

On many nights, Mr. Al-Ahdal, 25, has nothing to feed his 2-year-old daughter and his three boys, ages 3, 5 and 6. He consoles them with tea and sends them to bed.

“My heart hurts every time my child looks for food that is not there,” Mr. Al-Ahdal said. “But what can I do?”

The hunger gnawing at families in war-torn countries like Yemen highlights a broader crisis confronting billions of people in the world’s less-affluent economies as the consequences of Russia’s assault on Ukraine are compounded by other challenges — the continuing pandemic, a global tightening of credit and a slowdown in China, the second-largest economy after the United States.

Image

Walid Al-Ahdal with his children in their home at a camp in Marib, Yemen. “My heart hurts every time my child looks for food that is not there,” he said.Credit...Owis Alhamdani/UNICEF

Walid Al-Ahdal with his children in their home at a camp in Marib, Yemen. “My heart hurts every time my child looks for food that is not there,” he said.Credit...Owis Alhamdani/UNICEF

“It’s like wildfires in all directions,” said Jayati Ghosh, an economist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. “This is much bigger than after the global financial crisis. Everything is stacked against the low- and middle-income countries.”

The most direct repercussions are seen in the rising prices of cooking fuel, fertilizer and staple foods like wheat, disrupting agriculture and threatening nutrition in much of the world.

Sanctions imposed on Russia, a major oil and gas exporter, have constrained the supply of energy, sending prices skyward and limiting economic growth, especially in countries heavily dependent on imports.

High energy prices are at the center of diminished expectations for global economic growth, now estimated at 3.6 percent this year compared with 6.1 percent last year, according to a forecast from the International Monetary Fund.

More than 14 million people are now on the brink of starvation in the Horn of Africa, according to the International Rescue Committee — the result of a terrible drought combined with the pandemic and shortfalls of grains from Russia and Ukraine. The two countries are collectively the source for one-fourth of the world’s exports of wheat.

Last week, as India banned exports of most of its wheat, concerns deepened. India is the world’s second-largest wheat producer and holds abundant reserves.

The war in Ukraine threatens to impede the humanitarian response, lifting by as much as 16 percent the prices of components like peanuts that are blended into a therapeutic paste used to treat children facing life-threatening levels of malnutrition, UNICEF warned on Monday.

This catastrophe is unfolding as the pandemic continues to assail health systems, depleting government resources, and as the Federal Reserve and other central banks raise interest rates to choke off inflation. That is prompting investors to abandon lower-income countries while moving funds into less risky assets in wealthy economies.

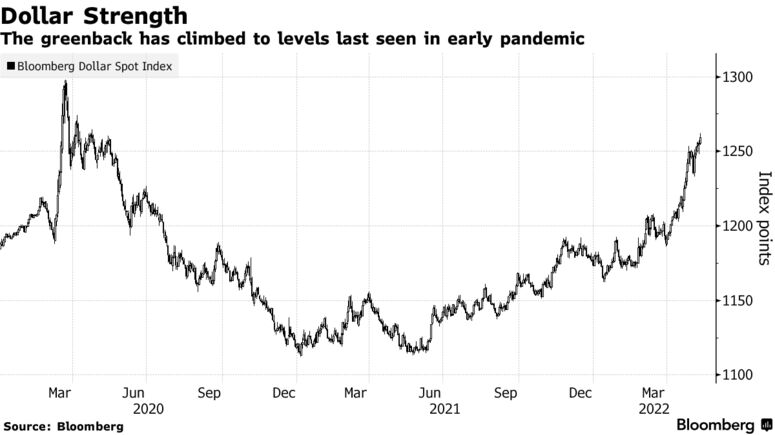

This tidal shift in the flow of money has lifted the U.S. dollar while pushing down the value of currencies from India to South Africa to Brazil, making their imports more expensive. Tighter credit is also increasing borrowing costs for heavily indebted governments.

Not least, China, long the engine of growth for many countries, has become a significant source of drag. As the Chinese government extends lockdowns to enforce its zero-Covid policy, the result is weaker demand for raw materials, parts and finished goods shipped to China from around the globe.

“I look at a perfect storm developing in places like Yemen, and many other places around the world,” said Philippe Duamelle, the UNICEF representative for Yemen. “Families have terrible choices to make.”

Image

Michael Moki, a motorcycle taxi driver in Douala, Cameroon, says the price of bread has risen while the portions have become smaller.Credit...Tom Saater for The New York Times

Not Enough Bread

On a fiercely hot morning in Cameroon’s largest city, Douala, Michael Moki, a motorcycle taxi driver, pulled up to a glass case containing a scattering of bread rolls.

A jovial man with a ready laugh, Mr. Moki, 34, ordered 500 Central African francs’ (about 80 cents) worth of rolls — breakfast for his family of five. When the vendor handed him the bag, the smile fell from his face.

“Your bread gets smaller every day, and the price increases,” he complained to the young man behind the counter. “Do you think I can eat all of this and get full?”

“The price of flour has gone up,” the vendor replied.

This kind of exchange has become commonplace in markets across Africa and parts of Asia.

The fighting in Ukraine has prompted farmers in Ukraine to flee their land, while Russia has blockaded Ukrainian ports on the Black Sea — vital conduits for exports. Last week, the World Food Program warned that the shutdowns of the ports threatened to worsen severe food insecurity in Ethiopia, South Sudan, Syria, Yemen and Afghanistan.

Russia and Ukraine supply all the wheat imported by Somalia and Benin, and at least two-thirds of the supply reaching Tanzania, Senegal, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan and Egypt, according to research from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

Globally, export prices for wheat and corn soared more than one-fifth in the month after Russia invaded Ukraine, according to the World Food Program.

Some economists accuse multinational agribusiness of exploiting the chaos caused by the pandemic and the war to lift prices beyond any connection to supply and demand. Ms. Ghosh, the economist, cited evidence that financial speculation is driving food prices higher.

In April, speculators were responsible for 72 percent of the buying activity on the Paris wheat market, up from 25 percent before the pandemic, according to data analyzed by Lighthouse Reports, a European journalism collaborative.

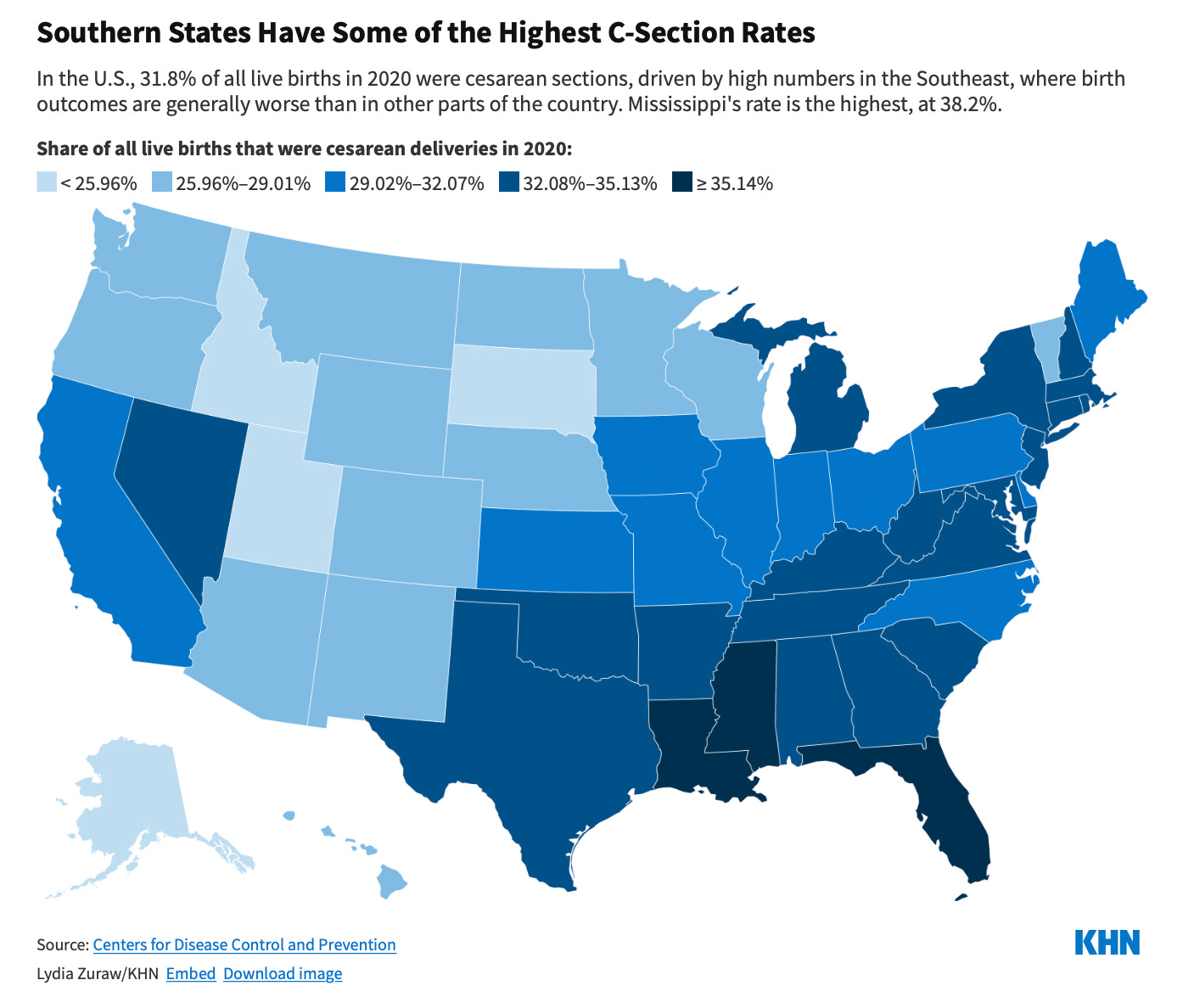

Many poor countries now confront an uncomfortable choice — increasing spending to aid their populations while adding to their debts, or imposing budget austerity and courting social conflict. Last week, public rage over rapid inflation amid a spiraling debt crisis in Sri Lanka triggered the downfall of the government. The risks of upheaval look dire in Tunisia, Ghana, South Africa and Morocco, Oxford Economics warned in a recent report.

For Mr. Moki, the motorcycle taxi driver, the source of strife was immediate. Returning to his two-room apartment, he faced disappointment from his wife over his meager breakfast haul.

Their landlord is increasing their rent from a barely affordable 50,000 francs ($80) a month to 75,000 francs ($120), citing his own higher costs.

“Things are becoming very difficult for us,” Mr. Moki said.

Culling the Herd

Sencer Solakoglu, a dairy farmer in Turkey, is getting squeezed by forces beyond his control.

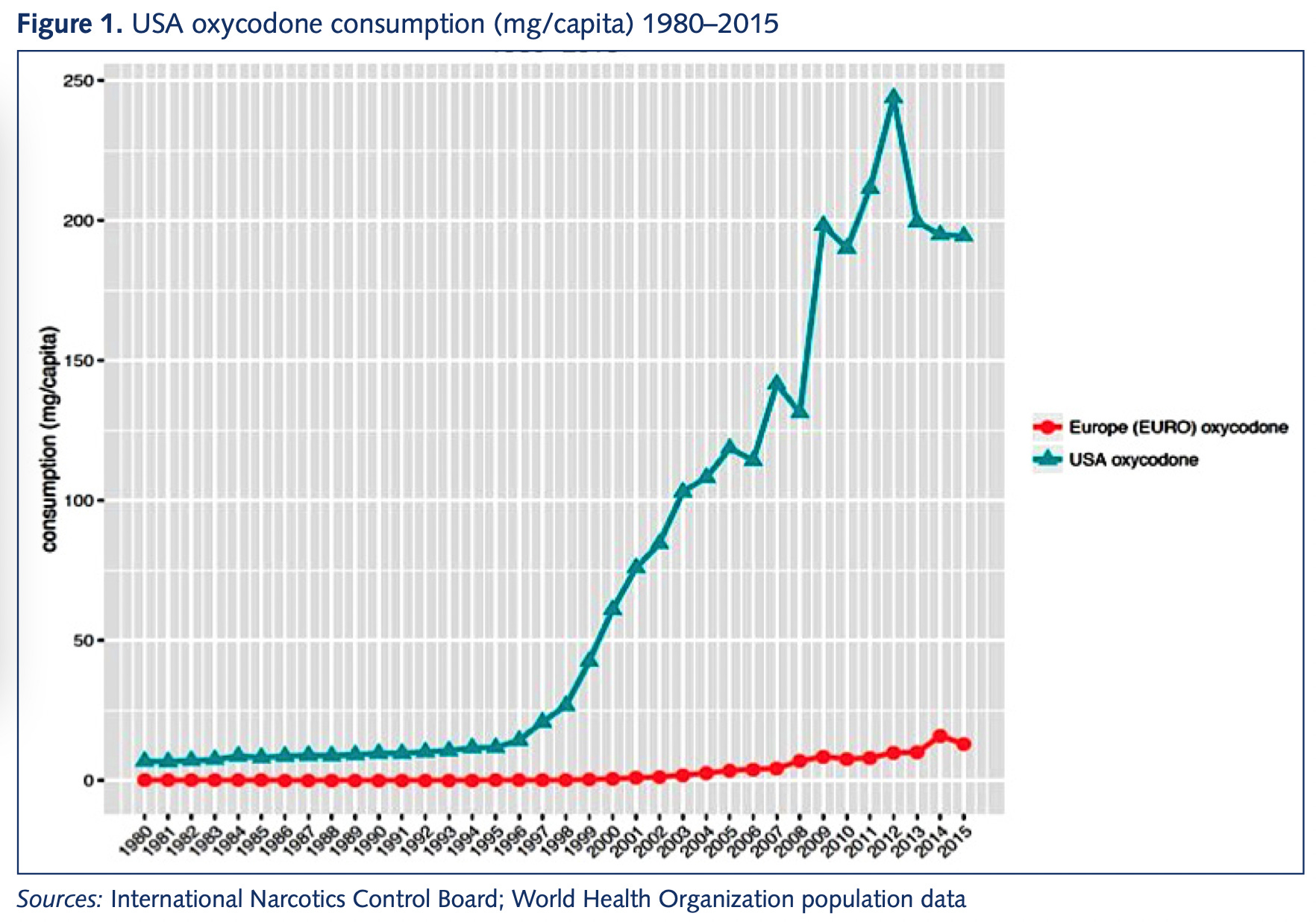

The prices of animal feed like hay, corn and alfalfa — much of it imported from Russia and Ukraine — have doubled and tripled in recent months. Yet the government, fearing public anger over inflation, has pressured farmers to forgo price increases, limiting Mr. Solakoglu’s ability to recoup his costs.

Turkish households, battered by a long-running economic crisis, have cut back on milk, slashing his sales by roughly half.

This is how Mr. Solakoglu, whose farm sits outside the Turkish city of Bursa, found himself culling his dairy herd by 200 in recent months.

“We slaughtered every cow that produced less than 30 kilograms (66 pounds) of milk per day,” he said.

These sorts of grim calculations have become routine in Turkey, a country that has gained intimate familiarity with economic distress.

Image

A produce market in Istanbul last month. Inflation in Turkey has soared, deepening a cost-of-living crisis for many households.Credit...Francisco Seco/Associated Press

Image

Preparing bread dough at a bakery in Istanbul.Credit...Burak Kara/Getty Images

After the global financial crisis of 2008, central banks in major economies like the United States and Europe dropped interest rates to near zero to spur growth. As international investors sought better returns, they piled into so-called emerging markets, accepting higher risks in exchange for greater rewards.

Turkey’s strongman president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, urged his cronies to avail themselves of international borrowing to finance enormous construction projects that kept the economy growing.

The Russia-Ukraine War and the Global Economy

Card 1 of 7

A far-reaching conflict. Russia’s invasion on Ukraine has had a ripple effect across the globe, adding to the stock market’s woes. The conflict has caused dizzying spikes in gas prices and product shortages, and is pushing Europe to reconsider its reliance on Russian energy sources.

Global growth slows. The fallout from the war has hobbled efforts by major economies to recover from the pandemic, injecting new uncertainty and undermining economic confidence around the world. In the United States, gross domestic product, adjusted for inflation, fell 0.4 percent in the first quarter of 2022.

Energy prices rise. Oil and gas prices, already up as a result of the pandemic, have continued to increase since the beginning of the conflict. The sharpening of the confrontation has also forced countries in Europe and elsewhere to rethink their reliance on Russian energy and seek alternative sources.

Russia’s economy faces slowdown. Though pro-Ukraine countries continue to adopt sanctions against the Kremlin in response to its aggression, the Russian economy has avoided a crippling collapse for now thanks to capital controls and interest rate increases. But Russia’s central bank chief warned that the country is likely to face a steep economic downturn as its inventory of imported goods and parts runs low.

Trade barriers go up. The invasion of Ukraine has also unleashed a wave of protectionism as governments, desperate to secure goods for their citizens amid shortages and rising prices, erect new barriers to stop exports. But the restrictions are making the products more expensive and even harder to come by.

Food supplies come under pressure. The war has driven up the cost of food in East Africa, a region that depends greatly on exports of wheat, soybeans and barley from Russia and Ukraine and is already dealing with a severe drought. Amid dwindling supplies, supermarkets around the world have begun asking customers to limit their purchases of sunflower oil, of which Ukraine is a top exporter.

Prices of essential metals soar. The price of palladium, used in automotive exhaust systems and mobile phones, has been soaring amid fears that Russia, the world’s largest exporter of the metal, could be cut off from global markets. The price of nickel, another key Russian export, has also been rising.

By 2017, investors fretted that the staggering debts held by Turkish companies posed the risk of defaults. They dumped the Turkish lira, pushing its value down roughly three-fourths by the end of last year.

That was the story before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and before central banks around the globe began raising interest rates.

By April, the lira was falling anew, and Turkey’s inflation rate was running at nearly 70 percent — its worst mark in two decades.

Even in countries facing less dire circumstances, farmers are grappling with malevolent arithmetic, as prices rise for animal feed, fertilizers and pesticides.

Indonesia has in recent years imported growing stocks of fertilizer from Russia. With fertilizer costs doubling in recent months, farmers have limited their application, diminishing their harvests.

“The current situation is the worst that we have ever seen,” said Ajat Sudrajat, a farmer in the Cipanas district of West Java, an agricultural area that serves Jakarta, Indonesia’s teeming capital.

Image

Food being distributed in Islamabad, Pakistan. The economy is drowning in debt and the country’s people are suffering from an unsustainable cost of living.Credit...Saiyna Bashir for The New York Times

Food being distributed in Islamabad, Pakistan. The economy is drowning in debt and the country’s people are suffering from an unsustainable cost of living.Credit...Saiyna Bashir for The New York Times

Impossible Debts

Two years ago, when Rubab Zafar and her husband, Muhammad Ali, left their village in rural Pakistan for new lives in Islamabad, they were full of optimism.

“There were no jobs in the village,” said Ms. Zafar, 31. “Islamabad is a big city, and we thought there would be some opportunity for us here.”

Instead, they have suffered the grind of a country grappling with impossible debts and downward mobility.

Ms. Zafar recently lost her babysitting job, while securing occasional part-time stints. Her husband works for a ride-hailing app. Collectively, they earn about 25,000 rupees a month (about $133), which barely covers the rent for their single room in a working-class neighborhood.

They are behind on their electrical bill, placing them in the same position as the Pakistani government, now in talks with the International Monetary Fund for an extension on a $6 billion package of loans.

Since 2016, Pakistan’s external debt payments have swelled to 38 percent of government revenue from about 9 percent, according to data tabulated by Debt Justice, an advocacy organization in England.

Debt payments have absorbed money that might otherwise support people like Ms. Zafar. Several times, she has applied for a cash grant, only to be turned away without explanation.

Downward Mobility

Brazil, a major exporter, is often portrayed as a beneficiary of rising commodity prices.

But in the shantytowns of Brazil’s major cities, where poverty frames daily life, people are focused on the exploding cost of liquefied petroleum gas, the cooking fuel used in 96 percent of homes.

Since February, the price of a canister of L.P. gas has increased nearly 10 percent, reaching its highest level in two decades, according to government data.

“It is the only thing we talk about,” said Vanderley de Melo Pereira, 55, a father of two in Rocinha, a teeming slum in Rio de Janeiro. “Since the war in Ukraine started, things have gotten worse.”

Across Latin America, the unfolding crisis threatens to erase decades of progress in boosting living standards.

“There are no prospects for growth,” said Liliana Rojas-Suarez, a regional expert and senior fellow at the Center for Global Development in Washington. “I think we’re going to have another lost decade.”

Ruth Maclean reported from Dakar, Senegal; Salman Masood from Islamabad, Pakistan; Elif Ince from Istanbul; Flávia Milhorance from Rio de Janeiro; Muktita Suhartono from West Java, Indonesia; and Brenda Kiven from Douala, Cameroon. Renato Dias in Rio de Janeiro contributed to this report.