Thursday, July 9, 2020

Enlighten Radio:Talkin Socialism Friday morning -- Ruthie Foster, Bonnie, and Rhiannon Giddens till then

Blog: Enlighten Radio

Post: Talkin Socialism Friday morning -- Ruthie Foster, Bonnie, and Rhiannon Giddens till then

Link: https://www.enlightenradio.org/2020/07/talkin-socialism-friday-morning-ruthie.html

--

Powered by Blogger

https://www.blogger.com/

Teleworking is Not Working for the Poor, the Young, and the Women [feedly]

https://blogs.imf.org/2020/07/07/teleworking-is-not-working-for-the-poor-the-young-and-the-women/

The COVID-19 pandemic is devastating labor markets across the world. Tens of millions of workers lost their jobs, millions more out of the labor force altogether, and many occupations face an uncertain future. Social distancing measures threaten jobs requiring physical presence at the workplace or face-to-face interactions. Those unable to work remotely, unless deemed essential, face a significantly higher risk of reductions in hours or pay, temporary furloughs, or permanent layoffs. What types of jobs and workers are most at risk? Not surprisingly, the costs have fallen most heavily on those who are least able to bear them: the poor and the young in the lowest-paid jobs.

In a new paper, we investigate the feasibility to work from home in a large sample of advanced and emerging market economies. We estimate that nearly 100 million workers in 35 advanced and emerging countries (out of 189 IMF members) could be at high risk because they are unable to do their jobs remotely. This is equivalent to 15 percent of their workforce, on average. But there are important differences across countries and workers.

The nature of jobs in each country

Most studies measuring the feasibility of working from home follow job definitions used in the United States. But the same occupations in other countries may differ in the face-to-face interactions required, the technology intensity of the production process, or even access to digital infrastructure. To reflect that, the work-from-home feasibility index that we built uses the tasks actually performed within each country, according to surveys compiled by the OECD for 35 countries.

We found significant differences across countries even for the same occupations. It is much easier to telework in Norway and Singapore than in Turkey, Chile, Mexico, Ecuador, and Peru, simply because more than half the households in most emerging and developing countries don't even have a computer at home.

Who is most vulnerable?

Overall, workers in food and accommodation, and wholesale and retail trade, are the hardest hit for having the least "teleworkable" jobs at all. That means more than 20 million people in our sample who work in these sectors are at the highest risk of losing their jobs. Yet some are more vulnerable than others:

Young workers and those without university education are significantly less likely to work remotely. This higher risk is consistent with the age profiles of workers in the sectors hardest hit by lockdowns and social distancing policies. Worryingly, this suggests that the crisis could amplify intergenerational inequality.

Women could be particularly hit hard, threatening to undo some of the gains in gender equality made in recent decades. This is because women are disproportionately concentrated in the hardest-hit sectors like food service and accommodation. In addition, women carry a heavier burden of child care and domestic chores, while market provision of these services has been disrupted.

Part-time workers and employees of small and medium-sized firms face greater risk of job loss. Workers in part-time work are often the first to be let go when economic conditions deteriorate, and the last to be hired when conditions improve. They are also less likely to have access to health care and the formal insurance channels that can help them weather the crisis. In developing economies, in particular, part-time workers and those in informal work face a dramatically higher risk of falling into poverty.

The impact on low-income and precariously-employed workers could be particularly severe, amplifying long-standing inequities in societies. Our finding—that workers at the bottom of the earnings distribution are least able to work remotely—is corroborated by recent unemployment data from the United States and other countries. The COVID-19 crisis will exacerbate income inequality.

To compound the effect, workers at the bottom of the income distribution are already disproportionately concentrated in the hardest-hit sectors like food and accommodation services, which are among those sectors least amenable to teleworking. Low-income workers are also more likely to live hand-to-mouth and have little financial buffers like savings and access to credit.

How to protect the most vulnerable?

The pandemic is likely to change how work is done in many sectors. Consumers may rely more on e-commerce, to the detriment of retail jobs; and may order more takeout, reducing the labor market for restaurant workers.

What can governments do? They can focus on assisting the affected workers and their families by broadening social insurance and safety nets to cushion against income and employment loss. Wage subsidies and public-works programs can help them regain their livelihoods during the recovery.

To reduce inequality and give people better prospects, governments need to strengthen education and training to better prepare workers for the jobs of the future. Lifelong learning also means bolstering access to schooling and skills training to help workers displaced by economic shocks like COVID-19.

This crisis has clearly shown that being able to get online was a crucial determinant to people's ability to continue engaging in the workplace. Investing in digital infrastructure and closing the digital divide will allow disadvantaged groups to participate meaningfully in the future economy.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Tim Taylor: The Subway Map View of US Mortality and Health [feedly]

https://conversableeconomist.blogspot.com/2020/07/the-subway-map-view-of-mortality-and.html

Except for a few clinical preventive services, most hospitals and physician offices are repair shops, trying to correct the damage of causes collectively denoted "social determinants of health." Marmot has summarized these in 6 categories: conditions of birth and early childhood, education, work, the social circumstances of elders, a collection of elements of community resilience (such as transportation, housing, security, and a sense of community self-efficacy), and, cross-cutting all, what he calls "fairness," which generally amounts to a sufficient redistribution of wealth and income to ensure social and economic security and basic equity. ...

The power of these societal factors is enormous compared with the power of health care to counteract them. One common metaphor for social and health disparities is the "subway map" view of life expectancy, showing the expected life span of people who reside in the neighborhood of a train or subway stop. From midtown Manhattan to the South Bronx in New York City, life expectancy declines by 10 years: 6 months for every minute on the subway. Between the Chicago Loop and west side of the city, the difference in life expectancy is 16 years. At a population level, no existing or conceivable medical intervention comes within an order of magnitude of the effect of place on health. ...

How do humans invest in their own vitality and longevity? The answer seems illogical. In wealthy nations, science points to social causes, but most economic investments are nowhere near those causes. Vast, expensive repair shops (such as medical centers and emergency services) are hard at work, but minimal facilities are available to prevent the damage. In the US at the moment, 40 million people are hungry, almost 600 000 are homeless, 2.3 million are in prisons and jails with minimal health services (70% of whom experience mental illness or substance abuse), 40 million live in poverty, 40% of elders live in loneliness, and public transport in cities is decaying. ...

Decades of research on the true causes of ill health, a long series of pedigreed reports, and voices of public health advocacy have not changed this underinvestment in actual human well-being. Two possible sources of funds seem logically possible: either (a) raise taxes to allow governments to improve social determinants, or (b) shift some substantial fraction of health expenditures from an overbuilt, high-priced, wasteful, and frankly confiscatory system of hospitals and specialty care toward addressing social determinants instead. Either is logically possible, but neither is politically possible, at least not so far.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Census: Household Pulse Survey shows 34.9% of Households Expect Loss in Income; 25.9% Concerned about Housing [feedly]

http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/CalculatedRisk/~3/aVWHtjMUGsk/census-household-pulse-survey-shows-349.html

First, from @ernietedeschi

The @uscensusbureau Household Pulse Survey, which performed admirably in anticipating the June jobs report, now shows employment has fallen by about 1.3 million cumulatively over the last 2 weeks.This graph is from Ernie Tedeschi (former US Treasury economist).

Some of this may be seasonality or survey error, but it merits pause nonetheless.

Note: The question on lost income is always since March 13, 2020 - so this percentage will not decline.

From the Census Bureau: Measuring Household Experiences during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic

The U.S. Census Bureau, in collaboration with five federal agencies, is in a unique position to produce data on the social and economic effects of COVID-19 on American households. The Household Pulse Survey is designed to deploy quickly and efficiently, collecting data to measure household experiences during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Data will be disseminated in near real-time to inform federal and state response and recovery planning.This will be updated weekly, and the Census Bureau released the recent survey results last Wednesday. This survey asks about Loss in Employment Income, Expected Loss in Employment Income, Food Scarcity, Delayed Medical Care, Housing Insecurity and K-12 Educational Changes.

…

Data collection for the Household Pulse Survey began on April 23, 2020. The Census Bureau will collect data for 90 days, and release data on a weekly basis.

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.The data was collected between June 25 and June 30, 2020.

Definitions:

Loss in employment income: "Percentage of adults in households where someone had a loss in employment income since March 13, 2020."

This number is since March 13, and has increased slightly.

Expected Loss in Employment Income: "Percentage of adults who expect someone in their household to have a loss in employment income in the next 4 weeks."

34.9% of households expect a loss in income over the next 4 weeks. This is down from 38.8% in late April, but up from 32% the previous (the previous week was the reference week for the BLS employment report). This might suggest the job gains stalled after the data was collected for the June employment report.

Food Scarcity: Percentage of adults in households where there was either sometimes or often not enough to eat in the last 7 days.

About 10% of households report food scarcity.

Delayed Medical Care: "Percentage of adults who delayed getting medical care because of the COVID-19 pandemic in the last 4 weeks."

41.5% of households report they delayed medical care over the last 4 weeks. This has not declined.

Housing Insecurity: "Percentage of adults who missed last month's rent or mortgage payment, or who have slight or no confidence that their household can pay next month's rent or mortgage on time."

25.9% of households reported they missed last month's rent or mortgage payment (or little confidence in making this month's payment). This has increased from a low of 22.1% in the survey of June 4th - June 9th.

Without an extension of the extra unemployment benefits (expires at the end of July), we will likely see a significant increase in housing stress.

K-12 Educational Changes: "Percentage of adults in households with children in public or private school, where classes were taught in a distance learning format, or changed in some other way."

Essentially all households with children are reporting were not being taught in a normal format.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

NMHC: Rent Payment Tracker Finds Decline in People Paying Rent in July [feedly]

http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/CalculatedRisk/~3/1ZhrhQESMt8/nmhc-rent-payment-tracker-finds-decline.html

From the NMHC: NMHC Rent Payment Tracker Finds 77.4 Percent of Apartment Households Paid Rent as of July 6

The National Multifamily Housing Council (NMHC)'s Rent Payment Tracker found 77.4 percent of apartment households made a full or partial rent payment by July 6 in its survey of 11.4 million units of professionally managed apartment units across the country.CR Note: It appears fewer people are paying their rent compared to last year (down 2.3 percentage points from a year ago). In the previous surveys, over the last few months, people were paying their rents at about the same pace as last year. The disaster relief has been key to helping people pay their bills, especially the extra unemployment benefits and the PPP.

This is a 2.3-percentage point decrease from the share who paid rent through July 6, 2019 and compares to 80.8 percent that had paid by June 6, 2020. These data encompass a wide variety of market-rate rental properties across the United States, which can vary by size, type and average rental price.

"It is clear that state and federal unemployment assistance benefits have served as a lifeline for renters, making it possible for them to pay their rent," said Doug Bibby, NMHC President. "Unfortunately, there is a looming July 31 deadline when that aid ends. Without an extension or a direct renter assistance program, that NMHC has been calling for since the start of the pandemic, the U.S. could be headed toward historic dislocations of renters and business failures among apartment firms, exacerbating both unemployment and homelessness."

emphasis added

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Almost four months in, joblessness remains at historic levels: Congress must extend the extra $600 in UI benefits, which expires in a little more than two weeks [feedly]

https://www.epi.org/blog/almost-four-months-in-joblessness-remains-at-historic-levels-congress-must-extend-the-extra-600-in-ui-benefits-which-expires-in-a-little-more-than-two-weeks/

Last week, 2.4 million workers applied for unemployment insurance (UI) benefits. This is the 16th week in a row that unemployment claims have been more than twice the worst week of the Great Recession. Of the 2.4 million workers who applied for UI, 1.4 million applied for regular state unemployment insurance (not seasonally adjusted), and 1.0 million applied for Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA). PUA is the federal program for workers who are not eligible for regular unemployment insurance (UI), like gig workers. It took some time, but all states except New Hampshire and West Virginia are now reporting PUA claims.

It's important to note that some initial claims from last week are likely from people who got laid off prior to last week but either waited until last week to file a claim, or applied earlier and their application had been caught in an agency backlog. Why do I think that's likely? In May, there were more than 8 million initial claims in regular state UI programs, but last week's Job Opening and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) data show there were only 1.8 million layoffs, which is back to pre-virus levels. This suggests many May UI claims were from earlier layoffs, and that dynamic is likely still in play.

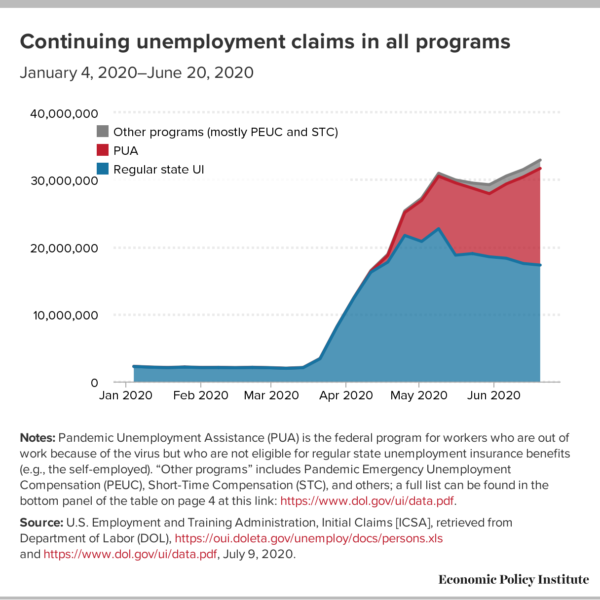

Figure A shows continuing claims in all programs over time (the latest data are for June 20). Continuing claims are more than 31 million above where they were a year ago. The latest figure in "other programs" in Figure A is 1.2 million claims. Most of this (0.9 million) is Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC). PEUC is the additional 13 weeks of benefits provided by the CARES Act for people who have exhausted regular state benefits. The number of people on PEUC can be expected to grow dramatically as the crisis drags on and more and more of the nearly 17 million people currently on regular state benefits exhaust their regular benefits and move on to PEUC.

"Other programs" in Figure A also includes Short-Time Compensation (STC). STC is a great alternative to layoffs where employers reduce work hours rather than lay off workers, and workers get partial UI. But DOL reports that just 360,000 workers are receiving STC.

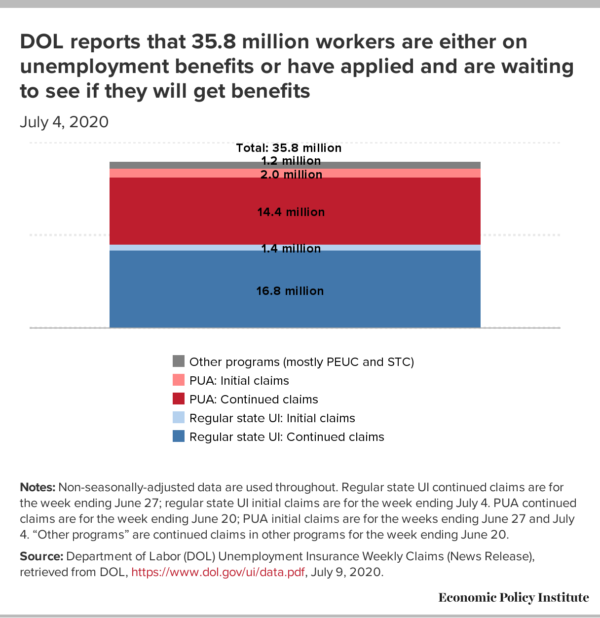

Figure A only covers continuing claims through June 20, but Figure B combines the most recent data on both continuing claims and initial claims to get a measure of the total number of people "on" unemployment benefits as of July 4th. DOL numbers indicate that right now, 35.8 million workers are either on unemployment benefits, have been approved and are waiting for benefits, or have applied recently and are waiting to get approved. That is more than one in five workers. But a note of caution: while regular state UI and PUA claims should be completely non-overlapping—that is how DOL has directed state agencies to report them—some states may be misreporting claims, so there may be some double counting. Further, some states may be including some back weeks in their continuing claims.

Note that of the 35.8 million workers DOL's numbers indicate are "on" unemployment benefits, close to half (45.8%) are on PUA. This is a stark reminder of the huge gaps are in our regular state UI programs and how important it is that Congress established PUA, and continue to fund it.

Today's data highlight the deep recession we are now in. It's important to remember that this recession is exacerbating existing racial inequalities by causing greater job loss in Black households than white households. Policymakers must do much more. For starters, they need to extend the across-the-board $600 increase in weekly unemployment benefits, which was probably the most effective part of the CARES Act. The extra $600 expires in a little more than two weeks (the CARES Act says the $600 applies to weeks "ending on or before July 31," which is a Friday. Since, in the UI world, weeks typically end on Saturday, the last payment will be for the week ending July 25).

Letting the extra $600 expire would be a disaster for UI recipients, who would have to drastically cut their spending, and for the economy, which is being held afloat by this spending. Letting the $600 expire would cost more than 5 million jobs over the next year. Federal lawmakers also need to provide massive aid to state and local governments. Without it, 5.3 million workers in the public and private sector will lose their jobs by the end of 2021.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Wednesday, July 8, 2020

New research finds enhanced U.S. social insurance will be necessary until the coronavirus recession recedes [feedly]

https://equitablegrowth.org/new-research-finds-enhanced-u-s-social-insurance-will-be-necessary-until-the-coronavirus-recession-recedes/

A new working paper released by Harvard University economist and former Equitable Growth Steering Committee member Raj Chetty and his Opportunity Insights colleagues finds that U.S. consumer spending fell dramatically over the past few months, driven by public health and safety concerns due to the novel coronavirus and COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus. These concerns are keeping people, especially those in high-income households, away from purchasing in-person services, indicating that until people feel safe engaging again in in-person services such as dining out or getting haircuts, consumer spending on services—which accounts for 66 percent of all consumer spending—will not meaningfully rebound.

In short, if policymakers want to fix the U.S. economy, then they must first fix the U.S. public health crisis. Merely announcing that the economy is "reopened" will not make it so. In the meantime, Chetty and his co-authors find that investing in social insurance programs—such as the expanded unemployment benefits enacted by Congress in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act—is the best way to mitigate economic suffering during the recession, rather than stimulus measures targeted toward businesses or the rich.

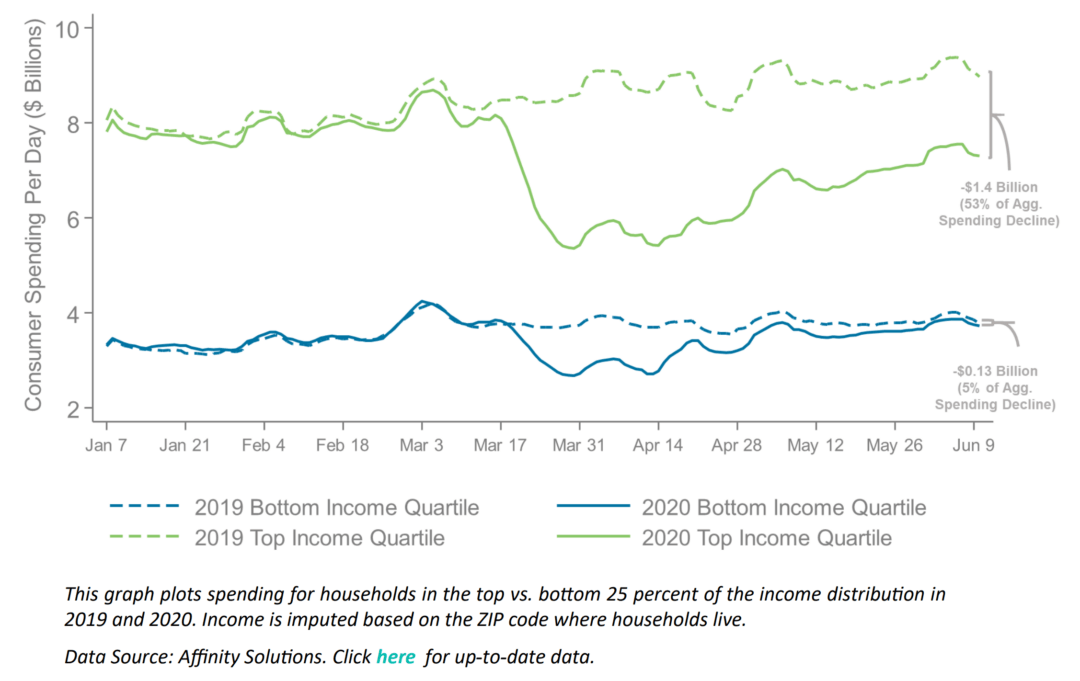

One of the key findings underlying the conclusions in this latest research is that the fall-off in consumer spending is being driven by high-income households, particularly in areas with high rates of COVID-19. The authors find that as of May 31, two-thirds of the total reduction in credit card spending since January was from households in the top 25 percent of the income distribution, whereas spending by households in the bottom quartile had returned to normal levels. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

High-income U.S. households have cut back sharply on spending

Consumer spending changes during the coronavirus recession, by income group, January 2020–June 2020

This fall-off in spending by the highest-income households is not driven by a decrease in their incomes, but rather because of the decline in in-person services they're buying, such as dining out, traveling, or haircuts. The authors find that spending on other services and luxury goods that do not require in-person contact—such as the installation of home swimming pools or landscaping services—actually increased slightly since the onset of coronavirus pandemic. This strongly suggests that public health concerns about contracting the novel coronavirus are driving the changes in spending patterns among the highest-income households, which also are more likely to have the luxury of working from home and maintaining self-isolation.

The findings by Chetty and his co-authors should come as no surprise because of what we already know about the differences in spending and savings patterns among low- and high-income households. Research by Harvard University economist and Equitable Growth Steering Committee member Karen Dynan and her co-authors finds that while Americans, on average, save about 20 cents of every dollar they earn and spend the rest, those in the top 5 percent save 37 cents, and those in the top 1 percent save 51 cents. Meanwhile, those in the bottom 20 percent save only one cent of every dollar. That's because higher-income households earn enough money to actually be able to put some of it aside in savings.

In contrast, because of rising inequality, stagnant wages, and deteriorating public institutions, low-income households have to spend all their income just meeting their basic needs—paying rent, putting food on the table, and securing childcare. Additionally, we know that lower-wage workers' accumulated savings don't amount to much of a cushion. Research from the Federal Reserve shows that 40 percent of U.S. adults would have a hard time handling an unexpected bill of $400. The Opportunity Insights research builds on this scholarship by demonstrating that there was less of a coronavirus-related fall-off in low-income households' spending because there were no fancy restaurant dinners out or Broadway theater tickets to eliminate from their budgets in the first place.

The trend in low-income households' spending, falling during the second half of March and then gradually returning to close to its original level, is also evidence of the success in government efforts to help replace low-income households' lost income from coronavirus-related job layoffs. Chetty and his co-authors find that in the week after April 15, when the $1,200 checks enacted by Congress in the CARES Act hit most Americans' bank accounts, spending by the bottom quartile of households increased by nearly 20 percentage points. Spending by the top quartile increased too, but by not even half as much, consistent with the different spending needs of high- and low-income households, as well as the much higher levels of savings among high-income families discussed above.

Chetty and his co-authors also examine two other recent government policies to prop up consumer spending and employment: state governments' declarations that they were reopening their economies and the Paycheck Protection Program, a $670 billion effort to provide loans to small businesses that convert to grants if employees are rehired. The researchers find that both of these efforts have had limited effects because they do not address the underlying cause of the fall-off in consumer spending—the public health concerns that are keeping people home, notwithstanding announcements about reopenings.

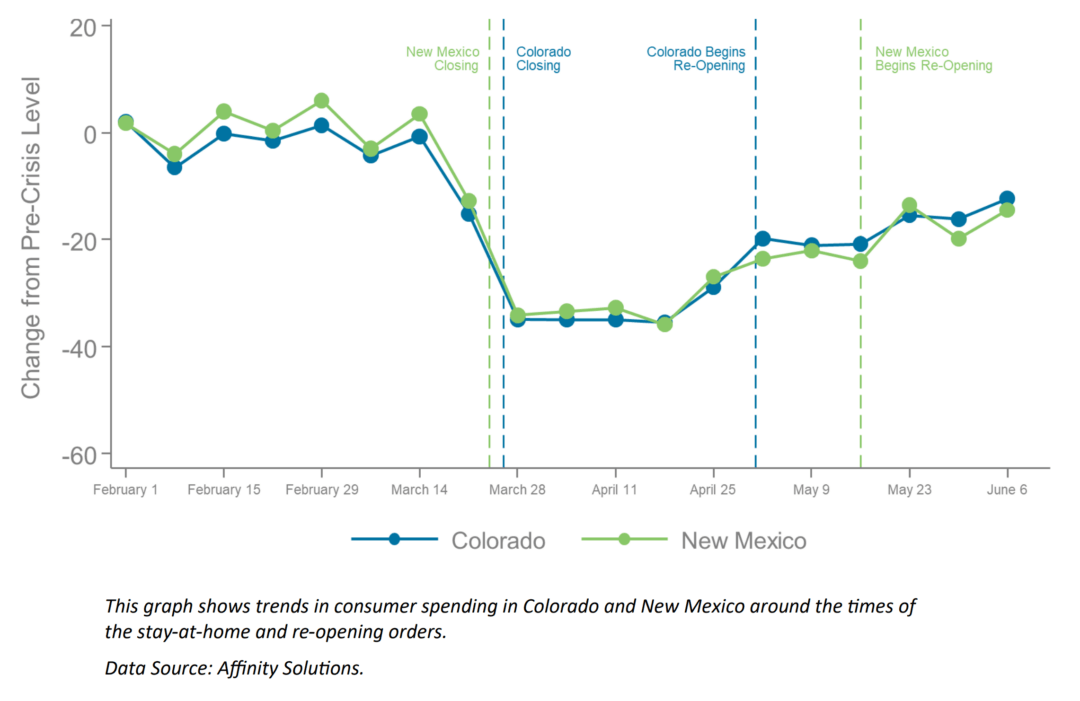

The authors offer a case study of Colorado and New Mexico. These two states issued stay-at-home orders within days of one another in late March, and then Colorado partially reopened its economy May 1 while New Mexico didn't do so until May 16. Despite this difference in reopening dates, there's no discernible difference in spending between the two during early May. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Different economic reopening dates did not make a difference in consumer spending

Effects of reopening on consumer spending in Colorado and New Mexico, February 2020–June 2020

Similarly, the authors' analysis of the Paycheck Protection Program find it had negligible effects on employment—total payroll at businesses fell by about 40 percent for both small firms eligible under the program and larger firms that weren't eligible. Instead, the researchers' analysis found that PPP loans were most likely to go to industries and the areas that were the least likely to experience job losses during the pandemic.

Professional, scientific, and technical services, for example, received a greater share of loans than did accommodation and food-service businesses. This is consistent with research recently highlighted by Equitable Growth from University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill economist T. William Lester, which showed that small, independent restaurants are suffering particularly acutely during the coronavirus recession, with current programs ill-suited to their needs.

The coronavirus and the economic recession it triggered have caused widespread physical and economic suffering. This latest research clearly illustrates that until the public health crisis is addressed, economic activity will not return to anything close to "normal," regardless of whether state officials declare their economies reopened. Therefore, government efforts to address the public health crisis must be improved.

In the meantime, policymakers should concentrate their efforts not on stimulus measures for the rich or for businesses, but on supporting the incomes of the tens of millions of workers who have lost their jobs, who are far more likely to have been low-income to begin with and have little savings to draw on. Most importantly, this includes extending the additional $600 in Unemployment Insurance benefits contained in the CARES Act, which are set to expire at the end of July.

This extra $600 is the easiest way to ensure that most workers and their families are able to get close to full wage replacement and continue to support themselves during what is increasingly looking like a prolonged economic recession. Other policies, such as providing stimulus for the rich, re-employment bonuses, or credit to businesses, will do little to reduce economic hardship when it is increasingly clear that economic activity simply will not come back while the threat of contagion continues.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

West Virginia GDP -- a Streamlit Version

A survey of West Virginia GDP by industrial sectors for 2022, with commentary This is content on the main page.

-

John Case has sent you a link to a blog: Blog: Eastern Panhandle Independent Community (EPIC) Radio Post: Are You Crazy? Reall...

-

---- Mylan's EpiPen profit was 60% higher than what the CEO told Congress // L.A. Times - Business Lawmakers were skeptical last...

-

via Bloomberg -- excerpted from "Balance of Power" email from David Westin. Welcome to Balance of Power, bringing you the late...