https://www.bradford-delong.com/2019/10/jos%C3%A9-azar-emiliano-huet-vaughn-ioana-marinescu-bledi-taska-and-till-von-wachter-_minimum-wage-employment-effects-a.html

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Cambridge - The rise of populist nationalism throughout the West has been fueled partly by a clash between the objectives of equity in rich countries and higher living standards in poor countries. Yet advanced-economy policies that emphasize domestic equity need not be harmful to the global poor, even in international trade.

At the beginning of classes every autumn, I tease my students with the following question: Is it better to be poor in a rich country or rich in a poor country? The question typically invites considerable and inconclusive debate. But we can devise a more structured and limited version of the question, for which there is a definitive answer.

Let's narrow the focus to incomes and assume that people care only about their own consumption levels (disregarding inequality and other social conditions). "Rich" and "poor" are those in the top and bottom 5% of the income distribution, respectively. In a typical rich country, the poorest 5% of the population receive around 1% of national income. Data are a lot sparser for poor countries, but it would not be too much off the mark to assume that the richest 5% there receive 25% of national income.

Similarly, let's assume that rich and poor countries are those in the top and bottom 5% of all countries, ranked by per capita income. In a typical poor country (such as Liberia or Niger), that is around $1,000, compared to $65,000 in a typical rich country (say, Switzerland or Norway). (These incomes are adjusted for cost-of-living, or purchasing-power, differentials so that they can be directly compared.)

Now, we can calculate that a rich person in a poor country has an income of $5,000 ($1,000 x 0.25 x 20) while a poor person in a rich country earns $13,000 ($65,000 x 0.01 x 20). Measured by material living standards, a poor person in a rich country is more than twice as well off as a rich person in a poor country.

This result surprises my students; most of them expect the reverse to be true. When they think of wealthy individuals in poor countries, they imagine tycoons living in mansions with a retinue of servants and a fleet of expensive cars. But while such individuals certainly exist, a representative of the top 5% in very poor countries is likely to be a mid-level government bureaucrat.

The larger point of this comparison is to underscore the importance of income differences across countries, relative to inequalities within countries. At the dawn of modern economic growth, before the Industrial Revolution, global inequality derived almost exclusively from inequality within countries. Income gaps between Europe and poorer parts of the world were small. But as the West developed in the nineteenth century, the world economy underwent a "great divergence" between the industrial core and the primary-goods-producing periphery. During much of the postwar period, income gaps between rich and poor countries accounted for the greater part of global inequality.

From the late 1980s on, two trends began to alter this picture. First, led by China, many parts of the lagging regions began to experience substantially faster economic growth than the world's rich countries. For the first time in history, the typical developing-country resident was getting richer at a faster pace than his or her counterparts in Europe and North America.

Second, inequalities began to increase in many advanced economies, especially those with less-regulated labor markets and weak social protections. The rise in inequality in the United States has been so sharp that it is no longer clear that the standard of living of the American "poor" is higher than that of the "rich" in the poorest countries (with rich and poor defined as above).

These two trends went in offsetting directions in terms of overall global inequality – one decreased it while the other increased it. But they have both raised the share of within-country inequality in the total, reversing an uninterrupted trend observed since the nineteenth century.

Given patchy data, we cannot be certain about the respective shares of within- and between-country inequality in today's world economy. But in an unpublished paper based on data from the World Inequality Database, Lucas Chancel of the Paris School of Economics estimates that as much as three-quarters of current global inequality may be due to within-country inequality. Historical estimates by two other French economists, François Bourguignon and Christian Morrison, suggest that within-country inequality has not loomed so large since the late nineteenth century.

These estimates, if correct, suggest that the world economy has crossed an important threshold, requiring us to revisit policy priorities. For a long time, economists like me have been telling the world that the most effective way to reduce global income disparities would be to accelerate economic growth in low-income countries. Cosmopolitans in rich countries – typically the wealthy and skilled professionals – could claim to hold the high moral ground when they downplayed the concerns of those complaining about domestic inequality.

But the rise of populist nationalism throughout the West has been fueled partly by the tension between the objectives of equity in rich countries and higher living standards in poor countries. Advanced economies' increased trade with low-income countries has contributed to domestic wage inequality. And probably the single best way to raise incomes in the rest of the world would be to allow a massive influx of workers from poor countries into rich countries' labor markets. That would not be good news for less educated, lower-paid rich-country workers.

Yet advanced-economy policies that emphasize domestic equity need not be harmful to the global poor, even in international trade. Economic policies that lift incomes at the bottom of the labor market and diminish economic insecurity are good both for domestic equity and for the maintenance of a healthy world economy that provides poor economies a chance to develop.

Dani Rodrik is Global Policy's General Editor and Professor of International Political Economy at Harvard's John F. Kennedy School of Government. he is also the author of Straight Talk on Trade: Ideas for a Sane World Economy.

This post first appeared on Project Syndicate and was reposted with permission.

Image: W H via Flickr (CC BY-ND 2.0)

The Trump Administration has invited states to set up so-called wellness programs, with individual-market insurers creating plans with higher premiums and out-of-pocket costs for people who don't meet certain health targets. Such programs would gut protections for people with pre-existing health conditions.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) barred individual-market insurers from charging higher premiums to people based on their health status, but the Administration is inviting states to undo that protection. Under its recent bulletin, up to ten states can establish a wellness program under which insurers, for example, charge premiums up to 30 percent higher to people who don't hit a weight-loss target or to reduce their cholesterol by a certain amount. (If the wellness program varies premiums based on tobacco use, insurers could raise premiums by up to 50 percent overall.)

A 30 percent premium differential could mean a significant financial hit of hundreds or thousands of dollars a year for those who don't achieve the targets. And such treatment would begin to look a lot like the discrimination that people with health conditions faced before the ACA.

States that want to establish a "health-contingent" wellness program would have to submit an application to the federal government, including an analysis showing that the state doesn't expect the wellness program to increase federal costs or reduce overall health coverage levels. But the federal government apparently wouldn't reject programs that are expected to drive sicker people out of the insurance market as long as more healthy people enroll to make up the difference.

Seema Verma, Administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which would decide whether to approve a state wellness program, said that this initiative would give states "the opportunity to not only improve the health of their residents but also to help reduce healthcare spending." But extensive research on wellness programs that employers have set up has failed to show that they do either. For example, a large randomized trial of an employer wellness program found that it had no effect on health outcomes or health behaviors, but it did reduce costs for people who were already healthier. That makes wellness programs a potential tool for employers looking to recruit or retain healthy over sick employees, the authors of that study note.

Individual-market wellness programs would have to meet the standards that apply to similar programs that employers offer, such as being made available to all individuals and providing a "reasonable alternative standard" for individuals to meet if they don't meet the initial health target. But as the research on employer programs shows, these standards don't prevent cost shifts from healthy to sick people.

And the consequences of such cost shifts would likely be worse in the individual market, where consumers may be paying all or most of their premium amount, and those who don't get the wellness discounts are more likely to find their premiums unaffordable and end up uninsured. Plus, if one individual-market insurer launches a wellness program that affects people's costs, the state's other insurers would have to follow suit or risk losing out to competitors that use the new program to attract healthier enrollees or discourage sicker customers from picking their plan. This sort of race to the bottom, where insurers compete on the health status of their customers instead of the price and quality of their plans, could leave people who have health issues with fewer affordable options in the individual market.

The wellness bulletin is just the latest example of how the Trump Administration is encouraging states to take steps that undermine the ACA. But, so far, no state has responded to the Administration's guidance encouraging states to use 1332 waivers to gut pre-existing condition protections, nor has any state weakened essential health benefits in response to the federal loosening of those rules. And more than a dozen states have stepped in to protect consumers against the spread of short-term health plans that don't cover pre-existing conditions, rather than letting federal rule changes expanding the availability of these plans carry the day.

The ACA's pre-existing condition protections are among the law's more popular and important elements. They help make the individual market accessible for people who had health issues in the past or may have them in the future. As they've previously done when the federal government has offered them the chance to undermine protections for people with pre-existing conditions, states should reject the invitation to set up discriminatory wellness programs.

Improving the lot of global supply chain workers involves not only organising local and migrant workers to pressure suppliers, brands and retailers, but leveraging the financial sector and state institutions.

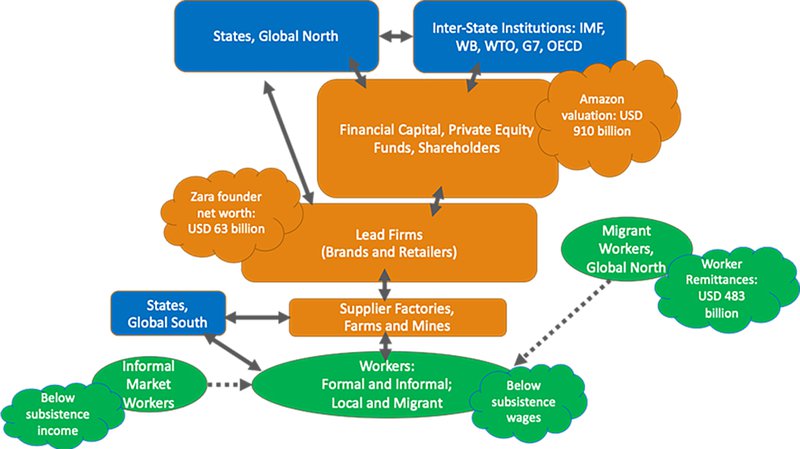

Power imbalances in global supply chains are used by multinational corporations to squeeze suppliers, and by suppliers to squeeze workers. Yet, supply chains involve far more than buyers, suppliers, and factory workers. Above buyers sit a range of financial sector actors demanding ever increasing returns on their investments, and above them are powerful states and inter-state institutions setting the rules of the game. In the past several decades, those rules have encouraged the proliferation of global supply chains through trade liberalisation and other policies.

At the same time, local factory workers are not the only ones squeezed at the bottom. So are informal sector workers, particularly women, and internal and external migrant workers. Many workers rely on family remittances to survive. They also purchase their goods from workers in the informal sector, whose under-valued labour helps to subsidise the dramatic profits and income of those at the top.

Tackling the challenges facing labour in global supply chains thus involves issues of factory work, the informal sector, and migrant labour. Efforts to achieve sustained improvements will require broad, strategic alliances that bring together labour unions, advocacy organisations for workers in the formal and informal sectors, migrant workers' rights groups, and the philanthropic groups who support these efforts. This broad social coalition will furthermore need to leverage all aspects of the supply chain structure, including suppliers, brands, retailers, the financial sector, states, and international institutions, to achieve positive and lasting change.

Wealth and power at the top of global supply chains

We now live in a world in which the CEO of Amazon, Jeff Bezos, earns $3,181 per second, which is more than the majority of supply chain workers in the global south earn in an entire year. Amancio Ortega, founder of clothing retailer Zara, has an estimated net worth of $62.7 billion. That is more than the total annual value of Bangladesh's apparel exports ($32 billion) and Vietnam's mobile phone and related components exports ($49 billion). The finance sector – whether it is via shareholders, private equity firms, or other financial instruments – wields enormous power and influence. It has been vital to this dramatic concentration at the top. Amazon's market valuation of $910 billion is more than that of the its next seven major competitors, including Walmart.

The top of the global supply chain does not end with the finance sector. One step higher are those who make the rules of the game that allow for this massive concentration of wealth and power. States in the Global North made the decisions to deregulate financial markets, especially in the United States. And inter-state institutions, such as the World Trade Organization in the 1990s, made the decisions that liberalised trade in sectors such as apparel, contributing to the further global dispersion of production.

The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank also have used their power and influence to deregulate labour markets and weaken freedom of association rights, which further facilitated the growth of supply chains by increasing downward pressure on wages and workers' rights. Hence, addressing worker rights problems in global supply chains also necessarily entails leveraging powerful state and inter-state actors to change the rules of the game.

Local, migrant, and informal workers in supply chains

While the role of buyers, the financial sector, and powerful states force us to look more closely at the top of supply chains, diverse worker experiences require us to examine how local labour, informality, and migrant workers all contribute to profit generation in supply chains. In the Dominican Republic, Haitian workers have been used for decades on sugar plantations to keep wages low and unions weak. In India, informal workers – many of them children facing horrifically unsafe conditions – mine the mica that goes into the makeup sold at considerable profit by multinational beauty products corporations. In Bangalore, India, internal migrant workers from northeast India increasingly make up the army of underpaid apparel export workers.

Informal markets for informal workers also help to subsidise those at the top of supply chains. Underpaid supply chain workers do not buy their goods in supermarkets. They shop in the informal sector, where the low income of market vendors reduces the cost of food and other basic goods. How often do we hear factory owners, brands, and retailers justifying the low wages paid to workers as acceptable because living expenses are relatively 'cheap' in producer countries? It's a common but deceptive argument. What is really happening is that underpaid supply chain workers are buying underpriced goods from underpaid informal sector workers. That is, underpaid informal sector work artificially deflates the costs of living, which permits suppliers to pay workers lower salaries, buyers to pay suppliers less for the products they make, and investors to enjoy better returns. The bottom of supply chains once again subsidises the top.

Worker remittances: subsidising supply chains

Completing this picture is the role of remittances. In 2018 migrant workers sent $482 billion back home to low- and middle-income countries. In El Salvador, remittances are approximately ten times the value of apparel exports. In Bangladesh, while four million garment workers receive less than $5 billion in annual wages, the country takes in over $15 billion in worker remittances. In Mexico, where workers labour in apparel, electronics and auto-parts supply chains, firms deliberately seek out communities with high levels of remittances in order to more easily pay less than a living wage. Migrant workers through their remittances (just like informal sector vendors) are thus partially subsidising the firms that sit at the top of global supply chains. Despite corporations' claims of the long-term development benefits of global supply chains, poverty reduction in many developing countries is far more likely to be the result of workers receiving remittances from poor workers abroad than it is a result of work in many global supply chains.

The structure of global supply and the role of factory, informal, and migrant workers. | Provided by author.

The way forward?

The problems facing workers in global supply chains are enormous. They include below subsistence wages, sexual harassment, verbal and physical abuse, inhumane production targets, unsafe buildings, and systematic and often violent efforts to deny workers their rights to organise, collectively bargain, and strike. Yet, the figure above provides some indication of what a comprehensive strategy for change might entail. To start, it requires continued and constant pressure on supplier factories, farms, and mines, and on brands and retailers to ensure respect of workers' rights in supply chains.

The figure also suggests that change entails targeting and leveraging the financial sector. This may include leveraging pension funds as part of campaigns or pushing for effective social investment standards. And it certainly entails targeting state and inter-state institutions that set the rules of the game for supply chains. This requires greater regulation of the financial sector, trade rules for sustainable development, immigration reform, comprehensive mandatory due diligence legislation, and binding treaties.

Private governance, such as the binding accords in Bangladesh and Lesotho, are also powerful and necessary instruments for change. The analysis above also points to myriad ways in which a full range of workers – local and migrant, formal and informal – contribute to the considerable wealth generated by supply chains. This highlights the crucial need to achieve full respect for freedom of association rights and organise all these workers through better labour laws and more effective enforcement so that they are empowered and engaged in collective responses to the enormous challenges they face.

The author thanks Catherine Bowman and Cathy Feingold for helpful feedback on earlier versions of this article.

Mark Anner is Associate Professor of Labour and Employment Relations and Political Science at Penn State University, and Director of the Center for Global Workers' Rights. He is also chair of the Program on Labour and Global Workers' Rights, which is part of the Global Labour University network. Mark spent 11 years working with labour unions and labour research centres in Central America and Brazil, and was a union organiser in Boston. He represented worker delegations at ILC 2016.

This first appeared on:

Services now seem to be transforming international trade in similar ways. Although they still only account for one fifth of cross-border trade, they are the fastest growing sector. While the value of goods exports has increased at a modest 1 per cent annually since 2011, the value of commercial services exports has expanded at three times that rate, 3 per cent. The services share of world trade has grown from just 9 per cent in 1970 to over 20 per cent today – and this report forecasts that services could account for up to one-third of world trade by 2040. This would represent a 50 per cent increase in the share of services in global trade in just two decades.

There is a common perception that globalization is slowing down. But if the growing wave of services trade is factored in – and not just the modest increases in merchandise trade – then globalization may be poised to speed up again.Of course, high-income countries around the world already have most of their GDP in the form of services. But it's not as widely recognized that emerging market economies already have a majority of their output in services, too, or very close.

Services already accounted for 76 per cent of GDP in advanced economies in 2015 – up from 61 per cent in 1980 – and this share seems likely to rise. In Japan, for example, services represent 68 per cent of GDP; in New Zealand, 72 per cent; and in the US, almost 80 per cent.

Emerging economies, too, are becoming more services-based – in some cases, at an even faster pace than advanced ones. Despite emerging as the "world's factory" in recent decades, China's economy is shifting dramatically into services. Services now account for over 52 per cent of GDP – a higher share than manufacturing – up from 41 per cent in 2005. In India, services now make up almost 50 per cent of GDP, up from just 30 per cent in 1970. In Brazil, the share of services in GDP is even higher, at 63 per cent. Between 1980 and 2015, the average share of services in GDP across all developing countries grew from 42 to 55 per cent.

Just because the services sector is playing a bigger role in national economies, this does not mean that the manufacturing sector is shrinking or declining. Many advanced economies are "post-industrial" only in the sense that a shrinking share of the workforce is engaged in manufacturing. Even in the world's most deindustrialized, services-dominated economies, manufacturing output continues to expand thanks to mechanization and automation, made possible in no small part by advanced services. For example, US manufacturing output tripled between 1970 and 2014 even though its share of employment fell from over 25 per cent to less than 10 per cent. The same pattern of rising industrial output and shrinking employment can be found in Germany, Japan and many other advanced economies. ...

This line between manufacturing and services activities, which is already difficult to distinguish clearly, is becoming even more blurred across many industries. Automakers, for example, are now also service providers, routinely offering financing, product customization, and post-sales care. Likewise, on-line retailers are now also manufacturers, producing not only the computer hardware required to access their services, but many of the goods they sell on-line. Meanwhile, new processes, like 3D printing, result in products that are difficult to classify as either goods or services and are instead a hybrid of the two. This creative intertwining of services and manufacturing is one key reason why productivity continues to grow.There are lots of issues here. For example, will the gains from trade in services end up benefiting mainly big companies, or mainly large urban areas, or will it allow small- and medium-sized firms in smaller cities or rural areas to have greater access to global markets? Many trade agreements about services are going to involve negotiating fairly specific underlying standards: for example, if a foreign insurance company or bank wants to do business in other countries, the solvency and business practices of that company will be a fair topic of investigation.

A survey of West Virginia GDP by industrial sectors for 2022, with commentary This is content on the main page.