https://www.globalpolicyjournal.com/blog/22/10/2019/struggle-work-dignity-through-broad-campaigns-and-social-alliances

Improving the lot of global supply chain workers involves not only organising local and migrant workers to pressure suppliers, brands and retailers, but leveraging the financial sector and state institutions.

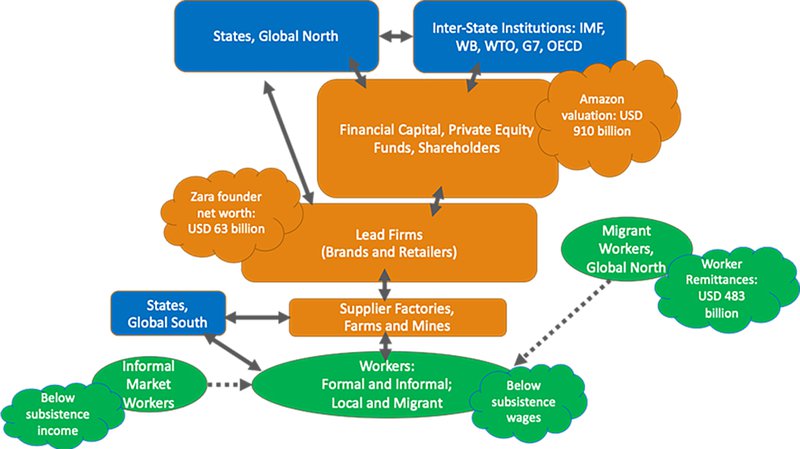

Power imbalances in global supply chains are used by multinational corporations to squeeze suppliers, and by suppliers to squeeze workers. Yet, supply chains involve far more than buyers, suppliers, and factory workers. Above buyers sit a range of financial sector actors demanding ever increasing returns on their investments, and above them are powerful states and inter-state institutions setting the rules of the game. In the past several decades, those rules have encouraged the proliferation of global supply chains through trade liberalisation and other policies.

At the same time, local factory workers are not the only ones squeezed at the bottom. So are informal sector workers, particularly women, and internal and external migrant workers. Many workers rely on family remittances to survive. They also purchase their goods from workers in the informal sector, whose under-valued labour helps to subsidise the dramatic profits and income of those at the top.

Tackling the challenges facing labour in global supply chains thus involves issues of factory work, the informal sector, and migrant labour. Efforts to achieve sustained improvements will require broad, strategic alliances that bring together labour unions, advocacy organisations for workers in the formal and informal sectors, migrant workers' rights groups, and the philanthropic groups who support these efforts. This broad social coalition will furthermore need to leverage all aspects of the supply chain structure, including suppliers, brands, retailers, the financial sector, states, and international institutions, to achieve positive and lasting change.

Wealth and power at the top of global supply chains

We now live in a world in which the CEO of Amazon, Jeff Bezos, earns $3,181 per second, which is more than the majority of supply chain workers in the global south earn in an entire year. Amancio Ortega, founder of clothing retailer Zara, has an estimated net worth of $62.7 billion. That is more than the total annual value of Bangladesh's apparel exports ($32 billion) and Vietnam's mobile phone and related components exports ($49 billion). The finance sector – whether it is via shareholders, private equity firms, or other financial instruments – wields enormous power and influence. It has been vital to this dramatic concentration at the top. Amazon's market valuation of $910 billion is more than that of the its next seven major competitors, including Walmart.

The top of the global supply chain does not end with the finance sector. One step higher are those who make the rules of the game that allow for this massive concentration of wealth and power. States in the Global North made the decisions to deregulate financial markets, especially in the United States. And inter-state institutions, such as the World Trade Organization in the 1990s, made the decisions that liberalised trade in sectors such as apparel, contributing to the further global dispersion of production.

The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank also have used their power and influence to deregulate labour markets and weaken freedom of association rights, which further facilitated the growth of supply chains by increasing downward pressure on wages and workers' rights. Hence, addressing worker rights problems in global supply chains also necessarily entails leveraging powerful state and inter-state actors to change the rules of the game.

Local, migrant, and informal workers in supply chains

While the role of buyers, the financial sector, and powerful states force us to look more closely at the top of supply chains, diverse worker experiences require us to examine how local labour, informality, and migrant workers all contribute to profit generation in supply chains. In the Dominican Republic, Haitian workers have been used for decades on sugar plantations to keep wages low and unions weak. In India, informal workers – many of them children facing horrifically unsafe conditions – mine the mica that goes into the makeup sold at considerable profit by multinational beauty products corporations. In Bangalore, India, internal migrant workers from northeast India increasingly make up the army of underpaid apparel export workers.

Informal markets for informal workers also help to subsidise those at the top of supply chains. Underpaid supply chain workers do not buy their goods in supermarkets. They shop in the informal sector, where the low income of market vendors reduces the cost of food and other basic goods. How often do we hear factory owners, brands, and retailers justifying the low wages paid to workers as acceptable because living expenses are relatively 'cheap' in producer countries? It's a common but deceptive argument. What is really happening is that underpaid supply chain workers are buying underpriced goods from underpaid informal sector workers. That is, underpaid informal sector work artificially deflates the costs of living, which permits suppliers to pay workers lower salaries, buyers to pay suppliers less for the products they make, and investors to enjoy better returns. The bottom of supply chains once again subsidises the top.

Worker remittances: subsidising supply chains

Completing this picture is the role of remittances. In 2018 migrant workers sent $482 billion back home to low- and middle-income countries. In El Salvador, remittances are approximately ten times the value of apparel exports. In Bangladesh, while four million garment workers receive less than $5 billion in annual wages, the country takes in over $15 billion in worker remittances. In Mexico, where workers labour in apparel, electronics and auto-parts supply chains, firms deliberately seek out communities with high levels of remittances in order to more easily pay less than a living wage. Migrant workers through their remittances (just like informal sector vendors) are thus partially subsidising the firms that sit at the top of global supply chains. Despite corporations' claims of the long-term development benefits of global supply chains, poverty reduction in many developing countries is far more likely to be the result of workers receiving remittances from poor workers abroad than it is a result of work in many global supply chains.

The structure of global supply and the role of factory, informal, and migrant workers. | Provided by author.

The way forward?

The problems facing workers in global supply chains are enormous. They include below subsistence wages, sexual harassment, verbal and physical abuse, inhumane production targets, unsafe buildings, and systematic and often violent efforts to deny workers their rights to organise, collectively bargain, and strike. Yet, the figure above provides some indication of what a comprehensive strategy for change might entail. To start, it requires continued and constant pressure on supplier factories, farms, and mines, and on brands and retailers to ensure respect of workers' rights in supply chains.

The figure also suggests that change entails targeting and leveraging the financial sector. This may include leveraging pension funds as part of campaigns or pushing for effective social investment standards. And it certainly entails targeting state and inter-state institutions that set the rules of the game for supply chains. This requires greater regulation of the financial sector, trade rules for sustainable development, immigration reform, comprehensive mandatory due diligence legislation, and binding treaties.

Private governance, such as the binding accords in Bangladesh and Lesotho, are also powerful and necessary instruments for change. The analysis above also points to myriad ways in which a full range of workers – local and migrant, formal and informal – contribute to the considerable wealth generated by supply chains. This highlights the crucial need to achieve full respect for freedom of association rights and organise all these workers through better labour laws and more effective enforcement so that they are empowered and engaged in collective responses to the enormous challenges they face.

The author thanks Catherine Bowman and Cathy Feingold for helpful feedback on earlier versions of this article.

Mark Anner is Associate Professor of Labour and Employment Relations and Political Science at Penn State University, and Director of the Center for Global Workers' Rights. He is also chair of the Program on Labour and Global Workers' Rights, which is part of the Global Labour University network. Mark spent 11 years working with labour unions and labour research centres in Central America and Brazil, and was a union organiser in Boston. He represented worker delegations at ILC 2016.

This first appeared on:

-- via my feedly newsfeed

No comments:

Post a Comment