Wednesday, March 15, 2017

EPIC Radio Podcasts:Are You Crazy? Dr John Aldis and Dr McGill discuss setbacks in fighting the opioid epidemic

Blog: EPIC Radio Podcasts

Post: Are You Crazy? Dr John Aldis and Dr McGill discuss setbacks in fighting the opioid epidemic

Link: http://podcasts.enlightenradio.org/2017/03/are-you-crazy-dr-john-aldis-and-dr.html

--

Powered by Blogger

https://www.blogger.com/

Tuesday, March 14, 2017

Re: [CCDS Members] Chart of the Week: The Productivity Puzzle [feedly]

https://blog-imfdirect.imf.org/2017/03/13/chart-of-the-week-the-productivity-puzzle/

By iMFdirect

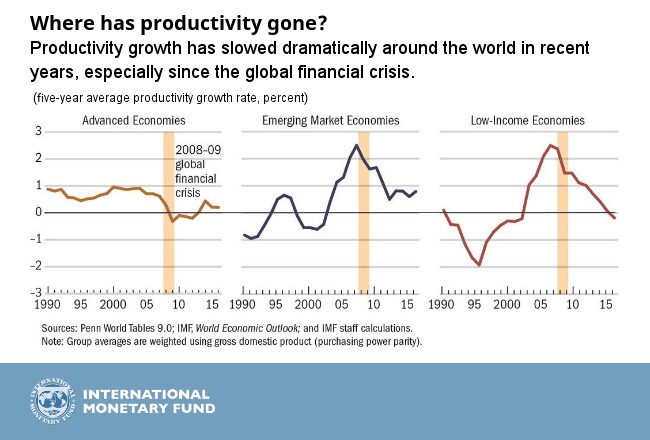

Technological change seems to be happening faster than ever. The prospect of driverless cars, robot lawyers, and 3D-printed human organs becoming commonplace suggests a new wave of technological progress.

These advances should raise our standard of living by producing more goods and services with less capital and fewer hours of work—that is, by being more productive. But, to paraphrase Nobel laureate Robert Solow, we can see it everywhere but in the productivity statistics.

The vexing truth is that output per worker and total factor productivity—which measures the overall productivity of both labor and capital, and reflects such elements as technology—have slowed sharply over the past decade.

What is going on? Some believe that aging populations in advanced economies has gradually become a drag on productivity. Others blame a fading information and communications technology boom. And the global financial crisis has played a decisive role, say the authors of Gone with the Headwinds: Global Productivity, an IMF paper due out on April 3.

Read more about why productivity is falling and what can be done about it in the March issue of Finance and Development:

Stuck in a Rut by Gustavo Adler and Romain Duval

Also watch this space for the April release of their IMF Staff Discussion Note.

*****

-- via my feedly newsfeed

_______________________________________________

CCDS Members mailing list

CCDS website: http://www.cc-ds.org

CCDS welcomes and encourages the full participation of our members in

this list serve. It is intended for discussion of issues of concern to

our organization and its members, for building our community, for

respectfully expressing our different points of view, all in keeping

with our commitment to building a democratic and socialist society. To

those ends, free and honest discussion of issues and ideas is

encouraged. However, personal attacks on named individuals, carrying on

old vendettas, excessive posts and, especially, statements that are

racist, sexist, homophobic, anti-semitic and/or anti-working class are not

appropriate.

Repeated failure to respect those principles of discussion

may result in exclusion from the list.

Please respect each other and our organization.

Any member of the list who objects to a posting on the list or the

behavior of a particular member should send email describing his or her

concerns to members-owner@lists.cc-ds.org

Post: Members@lists.cc-ds.org

List info and archives: https://lists.mayfirst.org/mailman/listinfo/members

To Unsubscribe, send email to:

Members-unsubscribe@lists.cc-ds.org

To Unsubscribe, change your email address, your password or your preferences:

visit: https://lists.mayfirst.org/mailman/options/members/phantom%40hevanet.com

You are subscribed as: phantom@hevanet.com

Re: [socialist-econ] Populism and the Politics of Health [feedly]

Sent from my iPhone

--Moderator: Krugman too! its all "white identity". Run away from Sanders in WV! Ignore labor! Shut up about austerity and CLASS inequalities! No more "universal benefits"! Except it might be GOOD to take away white Trump voters benefits, and punish them for not holding up the heaven of the Clinton and Obama eras which, for the median worker, yielded what in income? NOTHING.Obamacare was the only benefit and the Rs saw to it that that program's weaknesses were structured to provide an anti political base (for the "middle class" that did not get sufficient subsidies and for whom it was still a financial burden in an era off no raises). How stupid of them to be sucked into Trump!!K's solution: Let them get the screwing they deserve! Until their "white identity" is erased, presumably.Think this kind of thinking will put the fascist dog to sleep, friends????????I think not.Populism and the Politics of Health

http://economistsview.typepad.com/economistsview/2017/03/populism-and-the-politics-of-health.htmlPaul Krugman:

Populism and the Politics of Health: What's next on health care? Truly, I have no idea. The AHCA is a real stinker... But ... starting off the Trump legislative era with the crashing and burning of Obamacare repeal would deeply damage Trump... So they will pull out all the stops.But why are Republicans having so much trouble? Health reform is hard... But there's a more fundamental issue: who is being served?Obamacare helped a large number of people at the expense of a small, affluent minority: basically, taxes on 2% of the population to cover a lot of people and assure coverage to many more. Trumpcare would reverse that, hurting a lot of people (many of whom voted Trump) so as to cut taxes for a handful of wealthy people. That's a difference that goes beyond political strategy. ...And yet, and yet: Trump did in fact win over white working-class voters, who thought they were voting for a populist...This ties in with an important recent piece by Zack Beauchamp on the striking degree to which left-wing economics fails, in practice, to counter right-wing populism... Why?The answer, presumably, is that what we call populism is really in large degree white identity politics, which can't be addressed by promising universal benefits. Among other things, these "populist" voters now live in a media bubble, getting their news from sources that play to their identity-politics desires, which means that even if you offer them a better deal, they won't hear about it or believe it if told. For sure many if not most of those who gained health coverage thanks to Obamacare have no idea that's what happened.That said, taking the benefits away would probably get their attention, and maybe even open their eyes to the extent to which they are suffering to provide tax cuts to the rich. ...... Trumpism is faux populism that appeals to white identity but actually serves plutocrats. That fundamental contradiction is now out in the open.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "Socialist Economics" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to socialist-economics+unsubscribe@googlegroups.com.

To post to this group, send email to socialist-economics@googlegroups.com.

Visit this group at https://groups.google.com/group/socialist-economics.

To view this discussion on the web visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/socialist-economics/CADH2id%2BTx-DTmdEYkriFkiieE%3DE-mg_pYzCzx%3Dv2gqRB0eOkWQ%40mail.gmail.com.

For more options, visit https://groups.google.com/d/optout.

The Wrongest Profession [feedly]

http://cepr.net/publications/op-eds-columns/the-wrongest-profession

The Wrongest Profession

Dean Baker

The Baffler, Spring 2017

Over the past two decades, the economics profession has compiled an impressive track record of getting almost all the big calls wrong. In the mid-1990s, all the great minds in the field agreed that the unemployment rate could not fall much below 6 percent without triggering spiraling inflation. It turns out that the unemployment rate could fall to 4 percent as a year-round average in 2000, with no visible uptick in the inflation rate. As the stock bubble that drove the late 1990s boom was already collapsing, leading lights in Washington were debating whether we risked paying off the national debt too quickly. The recession following the collapse of the stock bubble took care of this problem, as the gigantic projected surpluses quickly turned to deficits. The labor market pain from the collapse of this bubble was both unpredicted and largely overlooked, even in retrospect. While the recession officially ended in November 2001, we didn't start creating jobs again until the fall of 2003. And we didn't get back the jobs we lost in the downturn until January 2005. At the time, it was the longest period without net job creation since the Great Depression.

When the labor market did finally begin to recover, it was on the back of the housing bubble. Even though the evidence of a bubble in the housing sector was plainly visible, as were the junk loans that fueled it, folks like me who warned of an impending housing collapse were laughed at for not appreciating the wonders of modern finance. After the bubble burst and the financial crisis shook the banking system to its foundations, the great minds of the profession were near unanimous in predicting a robust recovery. Stimulus was at best an accelerant for the impatient, most mainstream economists agreed — not an essential ingredient of a lasting recovery.

While the banks got all manner of subsidies in the form of loans and guarantees at below-market interest rates, all in the name of avoiding a second Great Depression, underwater homeowners were treated no better than the workers waiting for a labor market recovery. The Obama administration felt it was important for homeowners, unlike the bankers, to suffer the consequences of their actions. In fact, white-collar criminals got a holiday in honor of the financial crisis; on the watch of the Obama Justice Department, only a piddling number of bankers would face prosecution for criminal actions connected with the bubble.

There was a similar story outside the United States, as the International Monetary Fund, along with the European Central Bank and the European Union, imposed austerity when stimulus was clearly needed. As a result, southern Europe is still far from recovery. Even after another decade on their current course, many southern European countries will fall short of their 2007 levels of income. The situation looks even worse for the bottom half of the income distribution in Greece, Spain, and Portugal.

Even the great progress for the world's poor touted in the famous "elephant graph" turns out to be largely illusory. If China is removed from the sample, the performance of the rest of the developing world since 1988 looks rather mediocre. While the pain of working people in wealthy countries is acute, they are not alone. Outside of China, people in the developing world have little to show for the economic growth of the last three and a half decades. As for China itself, the gains of its huge population are real, but the country certainly did not follow Washington's model of deficit-slashing, bubble-driven policies for developing countries.

In this economic climate, it's not surprising that a racist, xenophobic, misogynist demagogue like Donald Trump could succeed in politics, as right-wing populists have throughout the wealthy world. While his platform may be incoherent, Trump at least promised the return of good-paying jobs. Insofar as Clinton and other Democrats offered an agenda for economic progress for American workers, hardly anyone heard it. And to those who did, it sounded like more of the same.

The Call of the Hawks

To get a clearer fix on how deeply our economics establishment is entrenched within its own counter-empirical worldview, let's home in on what is undoubtedly the most consequential article of faith in its catechism: the gospel of the deficit hawk.

Here's one handy way to break down the real-world costs of deficit hawkery. The cries for fiscal prudence that come from folks like Timothy Geithner and Paul Ryan, which are echoed in the media by the Washington Post and other major outlets, are costing us almost $2 trillion a year in annual output. This amount comes to more than $6,000 per person per year or $24,000 for an average family of four. These deficit hawks are ensuring that our children and grandchildren will live in poverty.

Yes, I'm inverting the traditional alarms raised by deficit hawks about the calamities of intergenerational indebtedness and throwing them in their faces, precisely so we can catalog the ways in which they've been spreading nonsense to push bad economic policies for decades. These bad policies have steep and lasting costs, especially following the collapse of the housing bubble and the Great Recession. The constant fear-mongering of the deficit hawks prevented the government from spending the money required to push the economy back to full employment. There was nothing to replace the construction and consumption spending that had been driven by the bubble.

As a result, the economy has operated well below its potential level of output since the recession began almost ten years ago. Not only has this meant needless unemployment, causing hardships for families with one or more unemployed worker; it has also produced long-term damage to the economy. Millions of workers have dropped out of the labor force. Some will never work again. In addition, when companies see weak demand, they invest less than they would have otherwise. The drop in investment slows the rate of productivity growth.

The combined impact of fewer workers and lower productivity is enormous. In 2008, before the true extent of the recession was known, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that by 2017 the economy's potential would be 29 percent larger than it had been in 2007. In its most recent report, the CBO puts the economy's potential for 2017 at just 16 percent more than its 2007 level. This difference of 13 percentage points translates into more than $2 trillion a year in today's economy.

It's also well worth noting that this lost output is income that disproportionately would have gone to those at the middle and bottom of the income ladder. The people who don't get employed in a weak economy are overwhelmingly African Americans, Hispanics, and workers with less education. Furthermore, in a weak labor market, workers at the middle and bottom of the wage ladder aren't well positioned to get wage increases. The weakness of the labor market in the Great Recession and the anemic recovery that followed were both associated with a large shift in national income from wages to profits. In short, this was a hard punch to the belly for large segments of the working population.

Is it fair to blame the severity of the recession and the weakness of the recovery on the deficit hawks? Yes. Suppose that the government had been free to spend without constraint in the years after the collapse of the housing bubble. There's no reason to believe that with a large enough stimulus, say two or three times the actual one, we would not have quickly moved the economy back to something close to full employment. This is the story of the massive spending associated with World War II that finally got the economy out of the Great Depression.

Of course, there is enormous uncertainty about how the economy would have responded following an event as traumatic as the collapse of the housing bubble. But even if just half the lost potential can be laid at the doorstep of the deficit hawks, the impact is still enormous. The $1 trillion in lost annual output is considerably larger than the amount raised each year through Social Security taxes. Even cutting the loss in potential GDP in half, the cost to the population is equivalent to an increase in the Social Security payroll tax of 14 percentage points.

Keep this 14 percentage point hike in the payroll tax in mind. The deficit hawks would scream bloody murder over a proposal to phase in a Social Security tax increase of 2 percentage points over two decades. The deficit hawks are not much concerned about consistency.

The Big-Numbers Cudgel

They have even less interest in clarity. Some of us stubbornly continue to think that those engaged in policy debates bear a minimum responsibility to inform Americans. But the deficit hawks seem to believe their greatest civic obligation is to scare people. We continually hear, from political demagogues and their policy enablers alike, about the $20 trillion national debt that we are passing on to our children. As House Speaker Paul Ryan recently put it, the need to "tackle the nearly $20 trillion national debt" is at the top of the country's priority list.

This line surely scores big in focus groups, where politicians test the best ways to alarm their audiences. However, it would fail if the point were to convey information. Few Americans have any idea how big the federal budget or the economy is. That means they have no way of assessing the meaning of a $20 trillion national debt. Sure, it's huge. But the debt would also be huge if it were $2 trillion or $200 trillion. Presenting a huge number like the $20 trillion national debt, without any context, tells audiences nothing.

This sort of game-playing happens with budget numbers all the time. If I wanted to convince readers that we were spending a huge amount trying to help the poor, I could say that we are spending more than $17 billion a year on Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), the program created by the 1996 welfare reform law. I might convince readers of our generosity to the world's poor by noting that we spend $31 billion a year on foreign aid. But people would probably be far less impressed if they were told that TANF spending was just over 0.4 percent of the total budget and foreign aid was equal to 0.8 percent of federal spending.

The practice of expressing budget numbers in dollar terms that virtually no one understands is inexcusable. I have harangued reporters on this point for decades. No journalist has ever tried to tell me that most of their readers understand numbers expressed in billions or trillions. Yet they refuse to make any effort to put these huge numbers in a context that could make them intelligible to readers, even when they acknowledge the need to do so. When she was the public editor of the New York Times, Margaret Sullivan urged the paper to address this problem, with strong agreement from David Leonhardt, then the Washington Bureau chief. Unfortunately, not much has changed in the Times' budget reporting or anyone else's.

That leaves us with a standard format for budget reporting that almost everyone agrees is deceptive, or at least uninformative. In this context, the path is clear for demagogic politicians to scare the public with misleading claims about the budget and the deficit. This is why we can count on endless tirades about the huge budget deficit and debt: it sells.

Threat Mis-Assessment

We can count on politicians and the groups funded by private-equity billionaire Peter Peterson to yell about large deficits and debt. The political fallout from deficits and debt is clear enough, but the more salient policy question is one you never see blaring across your news feeds and cable chyrons: What are the actual economic problems that we should expect to see from large deficits?

The standard story is that high budget deficits lead to high interest rates. Borrowing by the government increases the overall demand for borrowing in the economy. With more demand, interest rates rise. Higher interest rates will then discourage people from buying homes or cars, both of which are typically bought on credit. They will also discourage companies from investing in new plants and equipment. And to round out this supposedly vicious circle, higher interest rates will lead more foreign investors to buy financial assets in the United States. This pushes up the value of the dollar and leads to a larger trade deficit.

The budget deficit is bad news, we're told, because it means that we are investing less today than would otherwise be the case. Less investment translates into slower productivity growth, which means we will be poorer in future years. In addition, because we are borrowing from abroad, a larger share of what we do produce in the future will go to foreigners rather than domestic use. This is the basic story of why high deficits today are supposed to make things worse for our children and grandchildren.

High interest rates are at the center of this story, which then raises an obvious problem for the deficit hawks: interest rates are very low. While the key interest rate on 10-year Treasury bonds has risen since Donald Trump won the election, presumably on the expectation of larger budget deficits, it is still very low by historical standards, even at the early January level of 2.5 percent. In the low-deficit years at the end of the 1990s, the 10-year Treasury rate was generally in a range between 5 and 6 percent.

Even if interest rates were cooperating with the large budget deficit story, we would still be hard pressed to make the case that the deficit is poised to bankrupt our kids. Investment is actually not very responsive to interest rates. Using standard economic analyses, even large movements in budget deficits have relatively little impact on GDP.

For example, the CBO has projected that reductions in annual deficits even on the order of 3 percent of our GDP (approximately $570 billion in the 2017 economy, or more than $6.5 trillion over the next decade) would boost our GDP by less than a percentage point. Note that this is not a change in growth rates, but rather a cumulative change in output. In other words, if we were to trim annual spending by $570 billion next year, and maintain the lower level of spending for a decade, we would be rewarded in 2027 with a GDP just 1 percent larger than it would have been had we continued to maintain our current deficits.

The Never-Ending Backup Story

This is not the sort of projection that is likely to motivate people to slash government spending, so instead we get a far less honest and infinitely more alarmist account of the problem of deficits. We're told that because of interest payments on the debt and commitments to Social Security and Medicare, programs that primarily benefit the elderly, we will have little money to spend in other areas in five or ten years. In this story, we are screwing our children. We won't have the money to pay for education, infrastructure, research and development, and all sorts of other good things because all available cash will be devoted to retirees and to servicing the debt stoked by past entitlement spending.

There is so much in this scare story that is obviously wrong that it's hard to know where to begin. First, the scenario of an abrupt rise in interest payments posits that interest rates will rise to pre-recession levels, thereby causing interest payments to jump. This is possible, but it is a prediction that has consistently been proven wrong over the last six years. Perhaps if tax cuts and spending increases in the Trump administration goose demand, we'll begin to see the higher interest rates currently projected by the CBO. But that's an unlikely outcome if we go by the recent past.

Those who want to cut Social Security and Medicare, which certainly seems to be the core agenda of most deficit hawks, push forward without answering the obvious question of what alternative mechanism might secure retirement income and health care for seniors. The fact is, these public systems are immensely more efficient than their private-sector counterparts. Relying on the private sector will almost certainly lead to more waste in the economy — and, perhaps not coincidentally, more money for the financial industry.

We're also told that the well-off elderly don't need these benefits. There are two problems with this argument. The first is that the well-off elderly paid for these benefits just like everyone else. The richest elderly don't need the interest they get on government bonds, but no one would think of taking that away from them. The other problem is that there are not enough of them to make much of a difference. Just as Ronald Reagan promoted the urban legend of the system-gaming "welfare queen" in order to delegitimize income supports for poor mothers and children, the image of the heedless elderly millionaire feathering his or her nest with monthly Social Security payments is largely a self-interested social myth. Peter Peterson is fond of telling audiences that he doesn't need his Social Security. While that is surely true, there are not very many Peter Petersons among the over-sixty-five set. Even though we can get lots of money from taxing this small group of rich people, we couldn't get very much from taking away their benefits, primarily because Peter Peterson's Social Security check is not much larger than anyone else's. If we hope to save serious money by taking away benefits, we would have to be cutting benefits for retirees with incomes around $40,000 a year — not an income level ordinarily thought to make someone rich.

Getting Dovish with Deficits

If we don't follow the deficit hawks' advice and eviscerate Social Security and Medicare, how do we deal with the likelihood that spending on these programs will rise as a share of the federal budget? First, we need a clear and detailed picture of when the deficit poses a limit. Again, the classic deficit-hawk story is that the deficit is a problem when it pushes up interest rates. Since interest rates are still at extraordinarily low levels, the status quo should support a good deal of optimism about additional deficit spending.

Of course, we should take some mitigating factors into account. The current low level of interest rates stems at least in part from the Federal Reserve Board's decision to buy a vast number of government bonds. Analysts sometimes exaggerate the impact of this decision, but there's little doubt that it has reduced long-term rates by between 0.5 to 1.0 percentage points. In fact, since the rate on government debt is low, and since much of the interest is paid to the Fed and then refunded to the Treasury, the interest burden of the debt is actually near a post-war low when measured as a share of GDP. For some reason, the deficit hawks forget to mention this fact.

Suppose that in five or ten years we were to see the deficit start to rise due to the higher Social Security and Medicare spending associated with an aging population. As a first answer, we could simply run larger budget deficits. And suppose, in turn, that this increase started to send interest rates soaring as the deficit hawks always warn. We could have the Federal Reserve Board buy up the bonds to keep interest rates low — just as it did in the wake of the 2008 meltdown.

Having the Fed buy bonds is a perfectly reasonable policy as long as the economy is below its potential level of output. However, if it is actually hitting that level, putting more money into the economy to buy bonds would set up a classic case of turning too much money loose to chase too few goods and services. In other words, we would have serious problems with inflation. That's a real possibility, but it's worth remembering that we have been faced with the opposite problem of an inflation rate that is too low for almost a decade.

Suppose inflation does start to accelerate. Well, one thing we could do is raise taxes. We could raise taxes on the wealthy, but historically Social Security and Medicare have been financed through a payroll tax. The good news for any tax-raising scenario is that polls have indicated a strong willingness to pay higher taxes to support these hugely popular programs.

At this point, the deficit hawks typically start raising apocalyptic fears about higher taxes impoverishing our children. I have three responses to this claim.

The first is that we are all paying much higher Social Security and Medicare taxes than our parents and grandparents did. Are we therefore the victims of generational inequity? What's more, the main reason Social Security costs are rising is that our kids will live longer lives than we will. In other words, the dire specter of a generously subsidized cohort of older Americans is actually a sign of widespread social progress. (High Medicare costs are due to an incredibly inefficient health care system, but that's another story — one that deficit hawks are also in the midst of monkey-wrenching in order to delegitimize any state-supported solution.)

My second reply is that we should be worried about after-tax income, not the tax rate. Recall that austerity policies favored by deficit hawks may have already cost us the equivalent of an increase in the payroll tax of 14 percentage points. We're supposed to get hysterical over the prospect that our kids may pay 2 to 3 more percentage points in payroll taxes, but be unconcerned about this huge and needless loss of before-tax income?

More generally, if we manage to reverse the wage stagnation of the past thirty-plus years and see ordinary workers once more take a share of the gains of economic growth, their before-tax pay will be 40 to 50 percent higher in three decades than it is today. If they have to give back some of these gains in higher payroll taxes in order to support a longer retirement, it's hard to see just what the problem would be. (The bigger question, of course, is whether we can succeed in creating a political economy in which ordinary workers will once again share in generalized economic growth.) And taxes are just one way in which the government imposes costs on citizens. Donald Trump wants to have a massive infrastructure program financed by the creation of toll roads. These tolls will be paid to private companies and will not count as taxes. Feel better?

On a much larger scale, the government grants patent and copyright monopolies as an incentive for research and creative work. In the case of prescription drugs alone, these patent monopolies cost close to $350 billion a year (approximately 1.9 percent of GDP) over what the price of drugs would be in a truly free market. Even as deficit hawks try to convince us that the government can't afford to borrow another $50 billion a year to finance the research done by the pharmaceutical industry, they tell us not to worry about the extra $350 billion we pay for drugs because of government-granted patent monopolies. This monomaniacal obsession with tax burdens, to the exclusion of any reckoning with the burden of patent monopolies, shows yet again that the deficit hawks' oft-professed concern for our children's well-being is purely rhetorical, and in no way serious.

We should remember that we will pass down a whole society to our kids — including the natural environment that underwrites the quality of life of future generations. If the cost of ensuring that large numbers of children do not grow up in poverty and that the planet is not destroyed by global warming is a somewhat higher current or future tax burden, that hardly seems like a bad deal — especially if the burden is apportioned fairly. Now suppose, by contrast, that we hand our kids a country in which large segments of the population are unhealthy and uneducated and the environment has been devastated by global warming, but we have managed to pay off the national debt. That is, after all, the future that many in the mainstream of the economics profession are prescribing for the country. Somehow, I don't see future generations thanking us

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Trump Plans Big Federal Workforce Cuts, But Workforce Already at Record Lows, Undermining Basic Services [feedly]

http://www.cbpp.org/blog/trump-plans-big-federal-workforce-cuts-but-workforce-already-at-record-lows-undermining-basic

President Trump plans to propose large cuts in the number of federal employees, newsreports suggest, even though federal employment already equals its lowest level ever recorded (both as a

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Re: Thomas Piketty: Public Capital, Private Capital [feedly]

Public Capital, Private Capital

http://economistsview.typepad.com/economistsview/2017/03/ public-capital-private- capital.html

The present economic debate is over-determined by two realities which, moreover, are connected as we sometimes tend to forget. On one hand we have the steady rise in public debt and, on the other, the prosperity of privately owned wealth. The figures for the level of public debt are well known; almost everywhere the level approaches or exceeds 100% of national income (the equivalent of almost one year of gross domestic product) as compared with barely 30% in the 1970s. Far be it from me to minimise the extent of the problem: it is the highest level of public debt since World War Two and historical experience demonstrates that it is difficult to reduce this level of debt by ordinary means. This is precisely why, to get a clear idea of the issues at stake and the alternatives, it is essential to put this reality into perspective by relating it to developments in the structure of the property as a whole.

Briefly: the totality of what is owned in a country can be broken down into public capital, which is the difference between public assets (these include buildings, land, infrastructures, financial portfolios, shares in companies, etc. held by public authorities in different forms: State, municipalities, etc.) and public debt on one hand; and private capital, that is the difference between household assets and debts, on the other.

During the post-war boom (the Trente Glorieuses) public assets were very considerable (approximately 100-150% of national income, as a result of a very large public sector, a consequence of post-war nationalisations), and significantly higher than public debt (which was historically low at less than 30% of national income – after inflation, the cancellation of debts and the one-off levies on private capital in the years 1945-1955).

In total, public capital – net of debt – was largely positive, in the range of 100% of national income, despite the rising prices in real estate and on the stock market. At the same time, the public debt was approaching 100% of national income, with the result that net public capital became almost zero. On the eve of the crisis in 2008, it was already negative in Italy. The most recent data available for 2015-2016 shows that net public capital has become negative in the United States, Japan and the United Kingdom. In all these countries, the sale of the total public assets would not be sufficient to repay the debt. In France and in Germany net public capital is only just positive.

But this does not mean that rich countries have become poor: it is their governments which have become poor, which is very different. In fact, at the same time, private wealth – net of debt – has risen spectacularly. In the 1970s, private wealth represented 300% of national income in the 1970s, whereas in 2015 it had risen to, or exceeded, 600% in all the rich countries. This prosperity in private wealth is due to multiple causes: the rise in property prices (conglomeration effects in larger metropolitan areas), the aging of the population and decline in its growth (which automatically increases savings accumulated in the past in relation to current income and contributes to inflating the prices of assets) and also, of course, the privatisation of public assets and the rise in debt (which is held in one form or another by private owners, via the banks). One might add the very high returns obtained by the highest financial assets (which structurally grow faster than the size of the world economy) and an evolution in the legal system globally very favourable to private property owners (both in real estate and in intellectual property). The fact remains that private capital grew much faster than the decline in public capital, and that rich countries themselves hold and even a little more (in total, rich countries hold more financial assets in the rest of the world than the contrary).

Why be so pessimistic in the face of such prosperity? Simply because the ideological and political balance of power is such that public authorities are not able to make the main beneficiaries of globalisation contribute their fair share. The perception of this impossibility of a fair tax sustains the flight towards the debt. This feeling of disempowerment is reinforced by the unprecedented extent of economic and financial interdependence; each country is owned by its neighbours, particularly in Europe where there is a profound impression of loss of control.

Historically, major changes in the structure of property ownership often come together with profound political changes. We see this with the French Revolution, the American Civil War, the Euro-World Wars in the 20th century and the Libération in France. The nationalist forces at work today could lead to a return to national currencies and inflation, which would promote a chaotic redistribution of resources, at the expense of severe social stress and an ethnicisation of political conflicts. In the face of this fatal risk to which the present status quo could lead, there is only one solution. We must chart a democratic pathway out of the impasse and organise the necessary redistribution of resources within the framework of the rule of law.

(the figure on the share of public capital in national capital, also referred to in my last chronicle « On inequality in China« , is extracted from the following article: F. Alvaredo, L. Chancel, T. Piketty, E. Saez, G. Zucman, « Global Inequality Dynamics: New Findings from WID.world« ; data series in xlsx format are available here; all series can also be accessed on WID.world)

Partager cet article

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Harpers Ferry, WV

Thomas Piketty: Public Capital, Private Capital [feedly]

http://economistsview.typepad.com/economistsview/2017/03/public-capital-private-capital.html

The present economic debate is over-determined by two realities which, moreover, are connected as we sometimes tend to forget. On one hand we have the steady rise in public debt and, on the other, the prosperity of privately owned wealth. The figures for the level of public debt are well known; almost everywhere the level approaches or exceeds 100% of national income (the equivalent of almost one year of gross domestic product) as compared with barely 30% in the 1970s. Far be it from me to minimise the extent of the problem: it is the highest level of public debt since World War Two and historical experience demonstrates that it is difficult to reduce this level of debt by ordinary means. This is precisely why, to get a clear idea of the issues at stake and the alternatives, it is essential to put this reality into perspective by relating it to developments in the structure of the property as a whole.

Briefly: the totality of what is owned in a country can be broken down into public capital, which is the difference between public assets (these include buildings, land, infrastructures, financial portfolios, shares in companies, etc. held by public authorities in different forms: State, municipalities, etc.) and public debt on one hand; and private capital, that is the difference between household assets and debts, on the other.

During the post-war boom (the Trente Glorieuses) public assets were very considerable (approximately 100-150% of national income, as a result of a very large public sector, a consequence of post-war nationalisations), and significantly higher than public debt (which was historically low at less than 30% of national income – after inflation, the cancellation of debts and the one-off levies on private capital in the years 1945-1955).

In total, public capital – net of debt – was largely positive, in the range of 100% of national income, despite the rising prices in real estate and on the stock market. At the same time, the public debt was approaching 100% of national income, with the result that net public capital became almost zero. On the eve of the crisis in 2008, it was already negative in Italy. The most recent data available for 2015-2016 shows that net public capital has become negative in the United States, Japan and the United Kingdom. In all these countries, the sale of the total public assets would not be sufficient to repay the debt. In France and in Germany net public capital is only just positive.

But this does not mean that rich countries have become poor: it is their governments which have become poor, which is very different. In fact, at the same time, private wealth – net of debt – has risen spectacularly. In the 1970s, private wealth represented 300% of national income in the 1970s, whereas in 2015 it had risen to, or exceeded, 600% in all the rich countries. This prosperity in private wealth is due to multiple causes: the rise in property prices (conglomeration effects in larger metropolitan areas), the aging of the population and decline in its growth (which automatically increases savings accumulated in the past in relation to current income and contributes to inflating the prices of assets) and also, of course, the privatisation of public assets and the rise in debt (which is held in one form or another by private owners, via the banks). One might add the very high returns obtained by the highest financial assets (which structurally grow faster than the size of the world economy) and an evolution in the legal system globally very favourable to private property owners (both in real estate and in intellectual property). The fact remains that private capital grew much faster than the decline in public capital, and that rich countries themselves hold and even a little more (in total, rich countries hold more financial assets in the rest of the world than the contrary).

Why be so pessimistic in the face of such prosperity? Simply because the ideological and political balance of power is such that public authorities are not able to make the main beneficiaries of globalisation contribute their fair share. The perception of this impossibility of a fair tax sustains the flight towards the debt. This feeling of disempowerment is reinforced by the unprecedented extent of economic and financial interdependence; each country is owned by its neighbours, particularly in Europe where there is a profound impression of loss of control.

Historically, major changes in the structure of property ownership often come together with profound political changes. We see this with the French Revolution, the American Civil War, the Euro-World Wars in the 20th century and the Libération in France. The nationalist forces at work today could lead to a return to national currencies and inflation, which would promote a chaotic redistribution of resources, at the expense of severe social stress and an ethnicisation of political conflicts. In the face of this fatal risk to which the present status quo could lead, there is only one solution. We must chart a democratic pathway out of the impasse and organise the necessary redistribution of resources within the framework of the rule of law.

(the figure on the share of public capital in national capital, also referred to in my last chronicle « On inequality in China« , is extracted from the following article: F. Alvaredo, L. Chancel, T. Piketty, E. Saez, G. Zucman, « Global Inequality Dynamics: New Findings from WID.world« ; data series in xlsx format are available here; all series can also be accessed on WID.world)

Partager cet article

-- via my feedly newsfeed