https://www.epi.org/blog/the-carceral-state-and-the-labor-market/

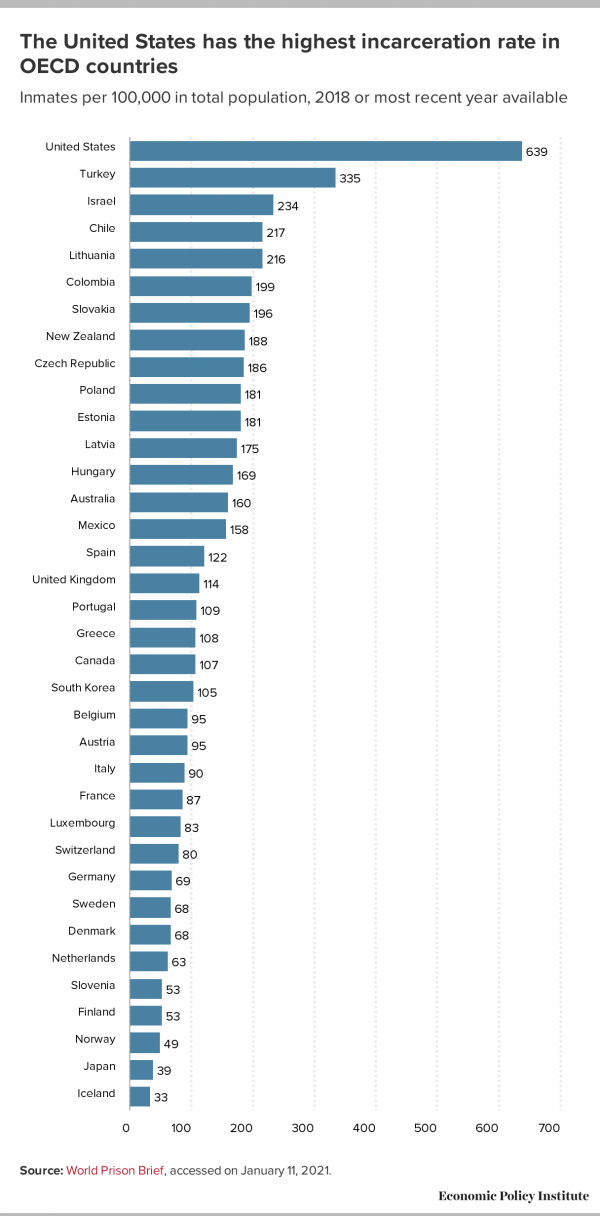

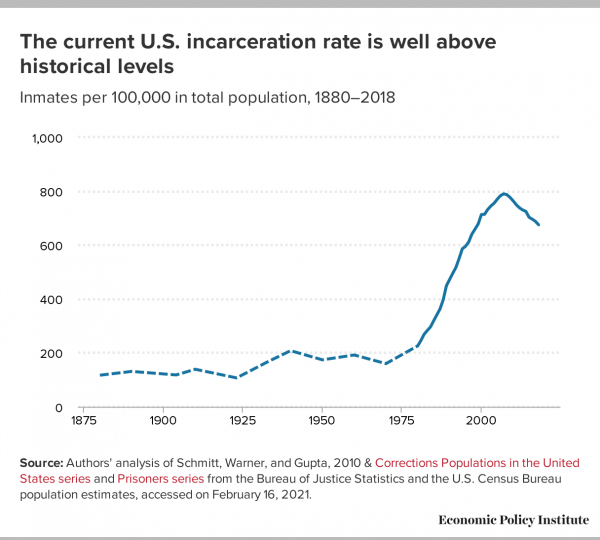

Mass incarceration is a core feature of contemporary society in the United States. According to the most recent available data, more than 2.1 million people are housed in America's local jails and state and federal prisons (BJS 2020b; BJS 2020c). Expressed as a share of the population, 639 of every 100,000 people in the country are in prison or jail, the highest incarceration rate, by a substantial margin, among the world's rich democracies (Figure A) and three times higher than the rate that prevailed in this country prior to the 1980s (Figure B).

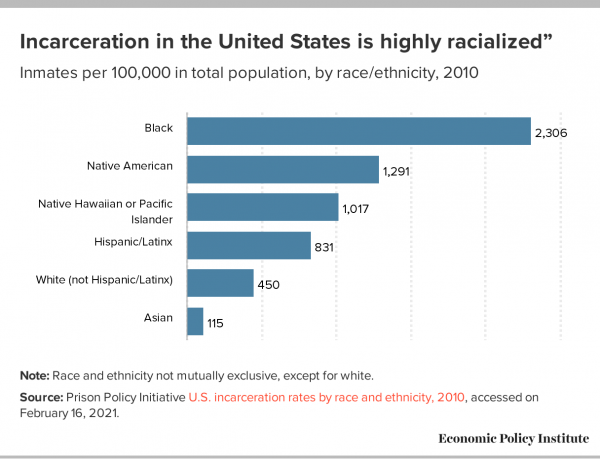

Incarceration is not just massive–it is also highly racialized. Relative to whites, the incarceration rate is almost twice as high for the Latinx population, almost three times as high for Native Americans, and more than four times higher for African Americans (Figure C).1

In many important respects, however, mass incarceration is only the tip of the iceberg. According to the most recent data available, in addition to the 2.1 million people in prison and jail about 10.1 million people were arrested; 3.5 million were on probation; 0.9 million were on parole; and anywhere from 14.0 million to 15.8 million had a history of incarceration or a felony conviction or both. As with the incarcerated, the population that has a history of incarceration or a felony conviction or both is disproportionately Black, Latinx, and Native American. (OJJDP 2020; BJS 2020a; Bucknor and Barber 2016)

The more than 15 million adults, disproportionately of color, with histories of felony conviction has profound implications for the functioning of the U.S. labor market (Bucknor and Barber 2016; Petach and Alves Pena 2020; Larson et al. 2020). The employment effects operate through multiple, often mutually reinforcing, channels.

Incapacitation

The most direct way in which the criminal justice system affects the labor market is by removing more than two million people, overwhelmingly of working-age, each year from the labor market. In discussions of criminal justice, the term "incapacitation" usually refers to removing convicted criminals from society to prevent them from committing further crime during the period that they are incarcerated. Incapacitation, however, also removes those same individuals from the ability to participate in the national labor market.

Many state and federal prisoners do work while serving their sentences, but they do not participate in any meaningful way in a labor "market" while in prison. Federal inmates are required to work if they are medically able, but the jobs they perform (food service, orderlies, groundskeeping, and other jobs) currently pay between 12 and 40 cents per hour.2 Pay in state prisons varies but is consistently very low. According to an analysis by the Prison Policy Institute, pay rates for most jobs in state prisons in 2017 were as low as 0 cents per hour (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas) and only $1.00–$2.00 per hour for some jobs in some states (Alaska, Connecticut, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, Pennsylvania, and Wyoming) (Prison Policy Initiative 2021).

Meanwhile, the main government survey of the labor market, the Current Population Survey, which provides official monthly estimates of the unemployment rate and the employment-to-population rate, does not gather data from residents of prisons and jails. As a result, government labor market statistics systematically exclude the incarcerated population.

Post-incarceration supply effects

The impact of incarceration on the labor market is not limited to the immediate incapacitation effects. The time spent in prison and jail can reduce the ability of inmates to succeed in the labor market long after they return to their communities.

Most obviously, inmates miss the opportunity to gain on-the-job work experience, which economists have identified as important for acquiring the skills that lead to higher wages, especially early in an individual's work life. Some jobs also come with general or job-specific training that can further increase the financial returns to work experience (Becker 1962; Mincer 1974; Altonji and Williams 1998).

The incarcerated population has on average, a much lower level of educational attainment than the rest of the U.S. population. While data on the educational data for the incarcerated are scarce, according to the most recent data compiled by the Prison Policy Initiative, about one fourth (25%) of the formerly incarcerated lack a high school degree, compared to about 13% in the country as a whole. Only 4% have a four-year college degree or more, compared to 29% nationally (Couloute 2018). In principle, prisons and jails can provide inmates with opportunities for education and training that could assist them after their release. In practice, these opportunities are poorly funded, limited in scope, and of inconsistent quality. As a result, inmates generally acquire little or no additional educational or vocational training while incarcerated (Bender 2018; Council of State Governments 2020; Sawyer 2019; Hobby, Walsh, and Delaney 2019).

A job can also build networks of coworkers that can help in job search with a current employer or in the labor market more broadly (Berg and Huebner 2011; Smith and Broege 2019). Inmates not only miss out on these expanded job networks, but their time in prison and jail may potentially serve to build thicker networks with people engaged in criminal activities.

The negative "labor supply" effects of incarceration are not limited to the impact on job skills and job networks. For many inmates, incarceration can have serious, long-term consequences for physical and mental health. Incarceration can reduce health after release directly through exposure to infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, hepatitis, and HIV, or more indirectly through exposure to acute and chronic stress (Massoglia and Pridemore 2015). The health effects for Black men may be particularly severe (Schnittker, Massoglia, and Uggen 2011).

Legal restrictions on individuals with felony convictions

Individuals with a criminal history, especially a felony conviction (even those who have never been incarcerated because of that conviction) face a host of legal barriers to employment. In a recent comprehensive analysis of the "collateral consequences" of a criminal history, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights calculated that more than 19,000 local, state, and federal laws directly limit employment prospects for individuals with criminal convictions. (U.S. Commission on Civil Rights 2019, Figure 1). Other collateral consequences of a criminal history that may indirectly reduce employment prospects include barriers to "obtaining housing, receiving public assistance, getting a driver's license, qualifying for financial aid and college admission, [and] qualifying for military service." (U.S. Commission on Civil Rights 2019, pp. 1-2) The Commission cites legal scholar Michael Pinard to summarize the impact: "the United States has a uniquely extensive and debilitating web of collateral consequences that continue to punish and stigmatize individuals with criminal records long after the completion of their sentences." (U.S. Commission on Civil Rights 2019, pp. 2)

Felony histories, stigma, and employer discrimination

Even absent explicit legal barriers to employment, employers may still discriminate against workers with a criminal record. An arrest, time in prison or jail, or a felony conviction may come with a stigma that makes employers less likely to make job offers (Holzer 1996; Holzer, Raphael, and Stoll 2004; Pager 2003, 2007) thereby reducing the employment prospects of those with a history of involvement with the criminal justice system.

Sociologist Devah Pager with various co-authors has conducted several careful "audit" studies of employer behavior toward job applicants of different races and ethnicities with and without felony convictions. In a study in Milwaukee in 2001, Pager sent matched pairs of actors to job interviews, where the trained male "applicants" varied by whether they were Black or white and whether they had a criminal record or not (Pager 2003). Applicants with a criminal record were much less likely than applicants without a criminal record to be given a call back interview. Only 17% of white applicants with a criminal record received a callback—half the 34% rate for white applicants with no criminal record. For Black applicants, the callback rate for those with a criminal record was only 5%, compared with a 14% rate for Black applicants without a criminal record. The combined effect of racial discrimination and a criminal record is evident in the Pager's finding that Black applicants without a criminal record had a lower probability of a callback (14%) than white applicants with a criminal record (17%).

In a subsequent study in New York City in 2004, Pager, Western, and Sugie (2009) followed a similar methodology and found that "a criminal record reduces the likelihood of a callback or job offer by nearly 50 percent (28 vs. 15 percent) (p. 4)." As in Milwaukee, they found that "the negative effect of a criminal conviction is substantially larger for blacks than for whites" with "the magnitude of the criminal record penalty suffered by black applicants (60 percent) …roughly double the size of the penalty for whites with a record (30 percent) (p. 4)."

The 2004 audit study also included Latino test applicants. Pager, Western, and Bonikoswski's (2009) analysis of the findings, which focused primarily on racial discrimination rather than discrimination against workers with a criminal record, did not report the direct results of the impact of a criminal record. They did note, however, that in their data a "white felon" had a callback or job offer rate lower (17.2%) than the average for all whites (31.0% for whites with and without a felony conviction). Consistent with the results in Milwaukee, the callback and job offer rate for whites with felony convictions (17.2%) was higher than the corresponding rate for Latino (15.4%) and Black (13.0%) with a "clean record" (Pager, Western, and Bonikoswski 2009, Figures 1 and 2).

Mass incarceration and related forms of government control over the millions involved with the criminal justice system are, through the channels described above, a threat to the economic well-being of those directly involved. Even more than that, the scale and the scope of what some scholars have called the "carceral state3"— from arrest to probation, imprisonment, parole, and post-incarceration and post-felony monitoring and control — are an active impediment to the functioning of the U.S. labor market, with particularly damaging effects for communities of color.4

Endnotes

1. For further discussion of the racial dimension of the U.S. criminal justice system, also see Alexander 2010, Kunsal 2005, Nellis 2016, and Sabol, Johnson, and Caccavale 2019.

2. See, for example, Federal Bureau of Prisons, "Work Programs," accessed February 21, 2021.

3. As sociologist Katherine Beckett (2018) has noted: "…many recent analyses seek to…map the development, operation, and effects of criminal justice institutions (including the police)…Studies aimed at this broader objective often us the term "carceral state" to call attention to the expanding role of penal institutions, broadly defined, in the lives of the poor and in communities of color" (p. 237)

4. For a recent empirical analysis of the connection between incarceration local labor markets, see Luke Petach and Anita Alves Pena (2021) and Ryan Larson et al (2020); for a recent empirical analysis of state differences in incarceration rates, see Sarah K. S. Shannon, Christopher Uggen, Jason Schnittker, Melissa Thompson, Sara Wakefield, and Michael Massoglia (2017). For a seminal discussion of the penal system as a core labor market institution, see Western and Beckett (1999).

References

Alexander, Michelle. 2010. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: The New Press.

Altonji, JG, and Nicolas Williams. 1998. "The effects of labor market experience, job seniority and job mobility on wage growth." Research in Labor Economics 17: 233–276.

Becker, Gary S. 1962. "Investment in Human Capital: A Theoretical Analysis." Journal of Political Economy 70, 9-49.

Beckett, Katherine. 2018. "The politics, promise, and perils of criminal justice reform in the context of mass incarceration." Annual Review of Criminology, 1: 235–259.

Berg, Mark T., and Beth M. Huebner. 2011. "Reentry and the ties that bind: an examination of social ties, employment, and recidivism." Justice Quarterly 28, no. 2: 382-410.

Bender, Katherine. 2011. "Education Opportunities in Prison Are Key to Reducing Crime" (blog post). Center for American Progress, March 2, 2018.

Bucknor, Cherrie, and Alan Barber. 2016. The price we pay: Economic costs of barriers to employment for former prisoners and people convicted of felonies. Center for Economic and Policy Research, June 2016.

Council of State Governments. 2020. Laying the Groundwork How States Can Improve Access to Continued Education for People in the Criminal Justice System. February 2020.

Couloute, Lucius. 2018. "Getting Back on Couse: Educational exclusion and attainment among formerly incarcerated people." Prison Policy Institute.

Hobby, Lauren, Brian Walsh, and Ruth Delaney. 2019, A Piece of the Puzzle: State Financial Aid for Incarcerated Students. Vera Institute of Justice, July 2019.

Holzer, Harry J. 1996. What employers want: Job prospects for less-educated workers. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Holzer, Harry J., Steven Raphael, and Michael A. Stoll. 2004. "The effect of an applicant's criminal history on employer hiring decisions and screening practices: Evidence from Los Angeles." National Poverty Center Working Paper Series 4, no. 15: 1–47.

Kunsal, Tushar. 2005. Racial disparities in sentencing: A review of the literature. The Sentencing Project, January 2005.

Larson, Ryan, Sarah Shannon, Aaron Sojourner, and Chris Uggen. 2020. "Felon History and Change in U.S. Employment Rates." Unpublished manuscript.

Massoglia, Michael and William Pridemore. 2015. "Incarceration and health." Annual Review of Sociology 41: 291–310.

Mincer, Jacob. 1974. Schooling, Experience and Earnings. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Nellis, Ashley. 2016. The color of justice: Racial and ethnic disparity in state prisons. The Sentencing Project, June 2016.

Pager, Devah. 2003. "The mark of a criminal record." American Journal of Sociology 108, no. 5: 937–75.

Pager, Devah. 2007. Marked: Race, crime, and finding work in an era of mass incarceration. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Pager, Devah, Bruce Western, and Bart Bonikowski. 2009. "Discrimination in a low-wage labor market: A field experiment." American Sociological Review 74: 777–799.

Pager, Devah, Bruce Western, and Naomi Sugie. 2009. "Sequencing disadvantage: Barriers to employment facing young Black and white men with criminal records." Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences 623, no. 1: 195–213.

Petach, Luke, and Anita Alves Pena. 2020. "Local labor market inequality in the age of mass incarceration" The Review of Black Political Economy 48, no. 1: 7-41.

Pinard, Michael. 2010. "Collateral consequences of criminal convictions: Confronting issues of race and dignity." New York University Law Review 85, no. 2: 457–534.

Prison Policy Initiative. 2010. "U.S. incarceration rates by race and ethnicity, 2010," [Excel file]. Accessed February 16, 2021.

Prison Policy Institute. 2021. How much do incarcerated people earn in each state? February 2021.

Sabol, William J., Thaddeus L. Johnson, and Alexander Caccavale. 2019. Trends in correctional control by race and sex. Council on Criminal Justice, December 2019.

Sawyer, Wendy. 2019. How Did the 1994 Crime Bill Affect Prison College Programs? (blog post). Prison Policy Institute, August 22, 2019.

Schmitt, John, Kris Warner, and Sarika Gupta. 2010. The High Budgetary Cost of Incarceration. Center for Economic and Policy Research, June 2010.

Schnittker, Jason, Michael Massoglia, and Christopher Uggen. 2011. "Incarceration and the health of the African American community." Du Bois Review Social Science Research on Race 8, no.1: 133–141.

Shannon, Sarah K. S., Christopher Uggen, Jason Schnittker, Melissa Thompson, Sara Wakefield, and Michael Massoglia. 2017. "The growth, scope, and spatial distribution of people with felony records in the United States, 1948–2010." Demography, 54: 1795-1818.

Smith, Sandra Susan, and Nora C.R. Broege. 2019. "Searching for work with a criminal record." Social Problems 67, no. 2: 208–232.

U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS). 2020a. Probation and parole in the United States, 2017–2018. August 2020.

U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS). 2020b. Correctional populations in the United States, 2017–2018. August 2020.

U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS). 2020c. Prisoners in 2019. October 2020.

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. 2019. Collateral consequences: The crossroads of punishment, redemption, and the effects on communities. June 2019.

Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP). n.d. "Law enforcement and juvenile crime" [CSV file], U.S. Department of Justice, last updated November 16, 2020.

World Prison Brief. 2021. "Highest to lowest – Prison population total." Accessed January 11, 2021.

Western, Bruce, and Katherine Beckett. 1999. "How unregulated is the U.S. labor market? The penal system as a labor market institution." American Journal of Sociology 104, no. 4: 1030–1060.

-- via my feedly newsfeed