by Matthew Boesler and Shruti Date Singh

For a decade the U.S. economy has been steadily drawing people into the workforce. Almost overnight, that machine crashed into reverse.Government-ordered shutdowns of restaurants and other businesses set off an avalanche of unemployment claims this week mere days after America hit red alert and began bracing for a pandemic. And it's exposing the systemic importance of a section of the workforce that's been quietly building through several boom-and-bust cycles.In Juan Sandoval's case, that's left

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-20/jobs-can-just-evaporate-at-unprecedented-pace-in-fragile-america

For a decade the U.S. economy has been steadily drawing people into the workforce. Almost overnight, that machine crashed into reverse.

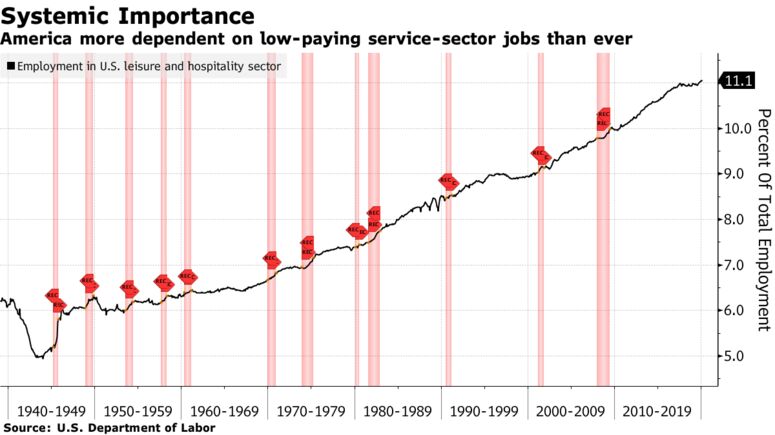

Government-ordered shutdowns of restaurants and other businesses set off an avalanche of unemployment claims this week mere days after America hit red alert and began bracing for a pandemic. And it's exposing the systemic importance of a section of the workforce that's been quietly building through several boom-and-bust cycles.

In Juan Sandoval's case, that's left him wondering what will happen to not one but both of his jobs.

Most Tuesdays, Sandoval puts in a six-hour shift at a fried chicken fast food chain in Chicago's West Loop, and then heads over to Italian Village Restaurants a few miles away for seven hours prepping salads at about $14 an hour.

This week, the 49-year-old father of two saw his hours reduced dramatically, and he's not sure if they'll call him in again.

He might be offered a shift preparing carry out at the fast food place, which is still possible during the Illinois dining ban. He may get a call from Italian Village when the ban expires at the end of March – if it in fact does.

Meanwhile, with a 70-hour workweek slashed to almost nothing, "I'm worried about if I'm going to get money for food and to pay my rent," he says.

A Burger King employee removes chairs from a store in San Francisco on March 17.

Photographer: David Paul Morris/Bloomberg

The economy has never been more dependent on jobs and incomes like these in the so-called leisure and hospitality sector –- restaurants, hotels and entertainment venues -- than it was on the eve of the virus outbreak.

More than one in 10 working Americans, about 16.9 million in total, were employed in these industries in February, a record.

Also at an all-time high: the share of consumer spending being directed toward those businesses -- about 8.6%, some $1.3 trillion a year.

Much of that economic activity is disappearing overnight -- shut down by decree, as local governments impose social-distancing measures designed to contain the spread of the deadly virus. That's reckoned to be the best way to give overburdened health-care systems a shot at treating the incoming wave of patients, and keeping the mortality rate down.

Transportation services -- which includes everything from airlines to Uber -- account for another $486 billion in annual consumer spending, and they're taking a big hit too.

It all adds up to massive job losses, at an unprecedented pace.

The unemployment rate in February was 3.5%, a 50-year low. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin warned Republican senators behind closed doors Tuesday it could surge to 20% if they don't act swiftly -- levels not seen since the Great Depression. A report the same day by firm Challenger, Gray & Christmas said the restaurant industry alone will shed 7.4 million jobs.

And it's already well underway.

Unemployment offices in several states reported jammed phone lines or website glitches this week, as claims piled in at a frantic pace. Filings for U.S. unemployment benefits are poised to surge to a record 2.25 million this week, according to a Goldman Sachs Group Inc. analysis of preliminary reports across 30 states.

Different Kind of Recession

What comes next isn't going to be anything like past recessions, according to Gabriel Mathy, an economics professor at American University in Washington.

Typically downturns start in the manufacturing sector, then spread to service industries – which tend to weather downturns relatively well. That's because in hard times consumers tend to delay purchases of big-ticket items like cars or washing machines, but they'll still try to squeeze in the occasional meal out or trip to the movies.

But with many of those businesses at risk of going under -- and the people employed by them being thrown out of work -- the rapid post-virus rebound that forecasters hope for may prove to be a pipe-dream.

People won't make up for all the times they didn't go out, especially if they've been without paychecks for weeks or months.

"Economists don't really have a good road map for this," said Mathy.

Rents Due

The risks could compound quickly, with rent payments due for millions at the start of next month. Robert West is already running the numbers in his head, like so many others.

West, 44, lost his job as a cook in a Philadelphia restaurant this week. He has some savings, but he's wondering how long they would last. And he says many of his younger co-workers don't have even that cushion, living paycheck to paycheck and scrambling for extra hours or shifts.

"A lot of people who rent are going to have trouble on April 1," West says.

Stimulus Help

Congressional leaders are racing to pass a virus package backed by President Donald Trump that would send checks out to every American, helping them to stay current on payments even if their income dried up. But even the most optimistic timetables wouldn't see the money arrive by the end of the month.

Some critics say it would be better to distribute the money via employers, who can then keep paying staff but also avoid bankruptcy themselves. Glenn Hubbard, an economist who advised President George W. Bush, says he's promoting such a plan among lawmakers.

In Chicago, Sandoval's boss at Italian Village -- Gina Capitanini, the third-generation owner of the restaurant –- says she worries about the people she's had to lay off because of the virus, and also about her business, which will suffer too.

That means Capitanini may not be in a position to re-hire everyone once this is all over. "Probably, financially, we wouldn't be able to do it," she said. "It's definitely going to be hunkering down."

No comments:

Post a Comment