https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2021/09/19/not-so-evergrande/

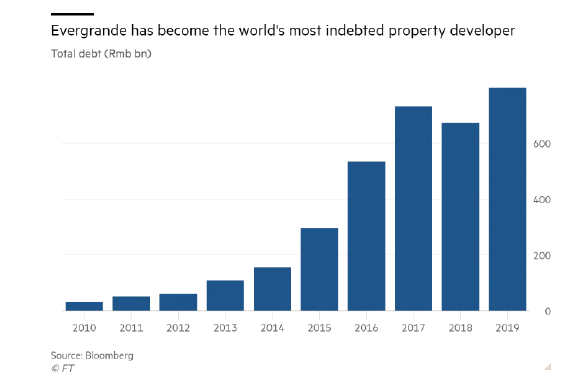

China's Evergrande Group is the second largest property developer in China and it is teetering on the brink of bankruptcy. Evergrande has hired 'restructuring advisers' and warned that its liquidity is under "tremendous pressure" from collapsing sales, facing protests by home buyers and retail investors. Based in Shenzhen in southern China, Evergrande is saddled with almost Rmb2tn of total liabilities or over $300bn.

The share price of the parent, 3333 HK, is down 76% from where it started the year. In August, Xu Jiayin, Evergrande's founder and one of China's wealthiest men, stepped down as chairman of the property group. Trading in the company's bonds has been suspended in Shanghai. Police descended on Evergrande's office building in Shenzhen when individual investors in the company's myriad "wealth-management" products gathered to demand repayment.

Evergrande's demise is a reflection of the dangers of uncontrolled property speculation in the capitalist sector of China's economy. Evergrande relies heavily on customers paying for flats before the projects are completed. The Evergrande property model is essentially a Ponzi scheme, where the company collects cash from the pre-sale of an ever-growing number of apartments, plus hundreds of thousands of individual investors and uses the cash to fund further sales by accelerating construction in progress and funding down-payments. Like any Ponzi, this works as long as it's accelerating. But when the market slows, those incoming streams of cash start to fall behind the growing arc of cash demands. Evergrande now has about 800 unfinished projects and there are about 1.2 million people waiting to move in.

Take one huge Evergrande project. Prices for Evergrande's Venice properties (situated on the coast 90km from Shanghai) have tripled since sales began in 2012 and 80% of the apartments have been sold in total, though about one-third are unoccupied. But this year sales have slowed. Data from the Qidong municipal housing bureau shows around 60% of the apartments that went on sale have been sold, despite a 15% price discount. Evergrande has now discounted all its apartments by as much as 30% and it has also sought to raise cash through spinning off its stakes in other companies.

What Evergrande reveals is the end game of the huge urbanisation drive that started off to house China's people. In a transformation of China's cities, the urbanisation rate surpassed 60% last year compared with 50% in 2011. But because this urbanisation was eventually conducted by the private sector for profit and based on owner-occupation (90% of Chinese own their homes mostly without mortgages), residential property construction has become a financial asset investment, just as it was and is in the major G7 economies. This 'financialisation' began in the late 1990s, when the government pursued a policy of making state-owned companies offload their residential assets to their employees – a Thatcher-type selling to council tenants. The idea was that the private sector would look after housing, not the state, from then on.

So instead of housing "being for living in" (Xi), it has become a sector "for speculation" (Xi). Apartments in China have become the investment vehicle of choice for people. Few buyers purchase an Evergrande apartment as their primary residence. And Evergrande has explicitly catered to the better-off Chinese, choosing locations that fall just outside of areas that restrict the number of units a person may buy and advertising the developments as second homes. All over China, even sales clerks and factory workers are sitting on empty Evergrande apartments and dreaming of selling them at a big mark-up to fund their children's study abroad or their own retirement.

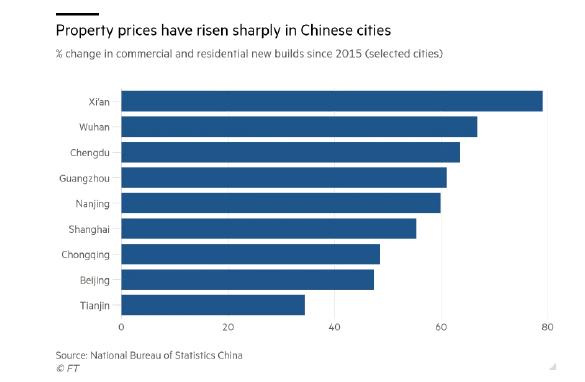

Property prices in coastal cities, where the best work and pay is, have doubled in the last ten years. In Shenzhen, the average apartment price has risen so much that some are finding it cheaper to live in Hong Kong, one of the most expensive property markets in the world. Since 2015, residential property prices have appreciated by more than 50% in China's largest cities. Over the past decade, average residential land supply per new resident in the top ten cities is only 230 square feet—little more than the size of a typical hotel room—or less than 60% of the average per capita residential space in China.

Speculation has been rife as local governments try to raise funds by selling land to developers which then build estates through borrowing at low rates often from the unregulated shadow non-bank sector. "Property is the single most important source of financial risk and wealth inequality in China," said Larry Hu, head of China economics at the foreign-owned Macquarie Securities Ltd. And he is right.

Much of the property speculation has been to build ever more commercial developments rather than housing. That's because the main prerogative for local governments is to accrue revenue. If they can attract more businesses into their jurisdictions and if those businesses become profitable, then the local government can collect more corporate taxes. At the same time, residential land supply is deliberately kept scarce so governments can make money on residential land sales. In effect, residential land sales serve as a cross-subsidy on local governments' pro-business land policy that sells commercial land cheaply.

The real estate sector now accounts for 13% of the economy from just 5% in 1995 and for about 28% of the nation's total lending. Given that local governments have $10 trillion in debt, land sales are the most crucial and reliable source of income for debt repayment. So any drastic changes would seriously raise the risk of local government defaults.

The private property sector's approach has relied on taking on large quantities of debt to accumulate more and more land — sometimes in speculative areas outside of major cities. In Evergrande's case, it has enough land to house the entire population of Portugal and more debt than New Zealand. In 2010, it had just Rmb31bn ($4.7bn) in debt and had $190bn of properties under development as of the end of 2020.

The group's mounting credit woes have coincided with the change in government policy towards the "disorderly expansion of capital"; against big technology groups, the real estate industry and other sectors. The country's housing ministry announced a three-year inspection campaign to tighten regulation of the property sector. Last year, the government implemented a strict policy aimed at reducing developers' leverage, which China's banking regulator has labelled the country's biggest financial risk. The banks have been told to jack up mortgage rates. Local governments are being directed to accelerate the development of government subsidized rental housing and have been told to increase scrutiny on everything from financing of developers and newly-listed home prices to title transfers.

And in a classic case of 'financialisation', Evergrande financed its activities by issuing what are called 'wealth management products', in effect mortgage-backed bonds for foreign and Chinese retail investors to buy, paying high interest rates (7-9%). Now the company is declaring its inability to meet these obligations. This uncontrolled expansion of debt by Evergrande and other property companies was ignored by China's regulatory authorities, just as it was in the US leading up to the property and financial bust in the global financial crash in 2008.

What is going to happen, if and when Evergrande goes bust? Will other property companies crash too?; are we heading for a huge financial crash in China and possibly globally, sparked by the end of China's property boom? Well, there are four other major Chinese property developers on the brink. The prices of the dollar bonds issued by these companies have collapsed on fears by international investors that those bonds cannot be refinanced when they mature, which would mean a default. So foreign investors in these bonds are taking a big ht. And the ability of these property developers to issue new debt to raise new money to refinance has disappeared.

But in my view, there is not going to be a financial crash in China. The government controls nearly everything, including the central bank, the big four state-owned commercial banks which are the largest banks in the world, the so-called 'bad banks', which absorb bad loans, big asset managers, most of the largest companies. The government can order the big four banks to exchange defaulted loans for equity stakes and forget them. It can tell the central bank, the People's Bank of China, to do whatever it takes. It can tell state-owned asset managers and pension funds to buy shares and bonds to prop up prices and to fund companies. It can tell the state bad banks to buy bad debt from commercial banks. So a financial crisis is ruled out because the state controls the banking system.

But if not a crash, what about the property bust and the high levels of debt incurred? Won't they reduce China's ability to grow at the pace previously achieved and targeted for the next five years? Western economists are clear on this: the debt is so large and China's productive sectors are now so weak that even if China avoids a financial crash, the hit to household incomes and the profits of the capitalist sector are large enough to reduce investment and GDP growth. China is heading for stagnation, if not a slump.

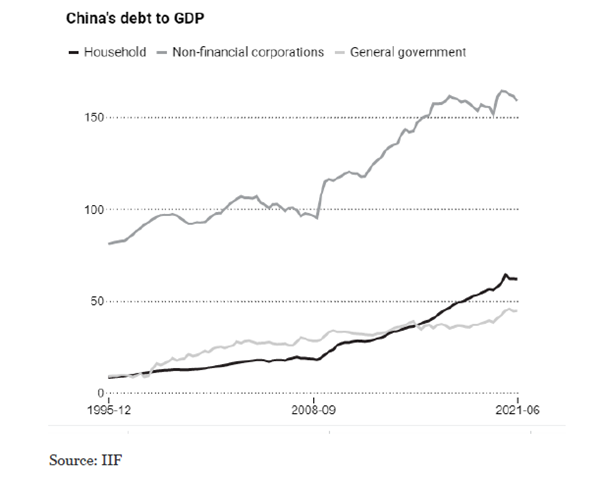

It's true that China has built up a debt mountain in recent years, of which property debt is a significant part. Total debt hit 317% of GDP in 2020. But most of this debt is in domestic currency and is owed by one state entity to another; from local government to state banks, from state banks to central government. When that is all netted off, the debt owed by households (54% of GDP) and corporations is not so high, while central government debt is low by global standards. Moreover, external dollar debt to GDP is very low (15%) and indeed the rest of the world owes China way more: 6% of global debt. China is a huge creditor to the world and has massive dollar and euro reserves, 50% larger than its dollar debt.

Chinese leaders want to curb the debt level. But as I have explained before, controlling the debt level can come in two ways; either through high growth from productive sector investment to keep the debt ratio under control; and/or by reducing credit binges in unproductive areas like speculative property. The latter would mean a reduction in the profitability of the capitalist sector in China and this would lower the potential for productive investment by that sector. So the loss of profits and household income from property busts would add to downward pressure on growth of output and incomes.

But that forecast is based on the view that the Chinese government should continue to rely ever more on its capitalist sector to deliver. And yet China's capitalist sector is in trouble in many ways just like in the G7 economies. Profitability in the capitalist sector has been falling and is now at all-time lows; and much of its activities are increasingly in 'unproductive' sectors like consumer finance, property or social media.

Again, as I have argued before, the basic contradiction of China's economy is not between investment and consumption, or between growth and debt; it is between profitability and productivity. The growing size and influence of the capitalist sector in China is weakening the performance of the economy and widening inequalities. In my view, the Chinese economy is now strong enough not to rely on foreign investment or on unproductive capitalist sectors for growth. Increasing the role of planning and state-led investment, the main basis of China's economic success over the 70 years of the People's Republic, has never been more compelling.

-- via my feedly newsfeed