https://economicupdate.podbean.com/e/economic-update-labor-and-capitalisms-rise-and-fall/

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Key takeaways:

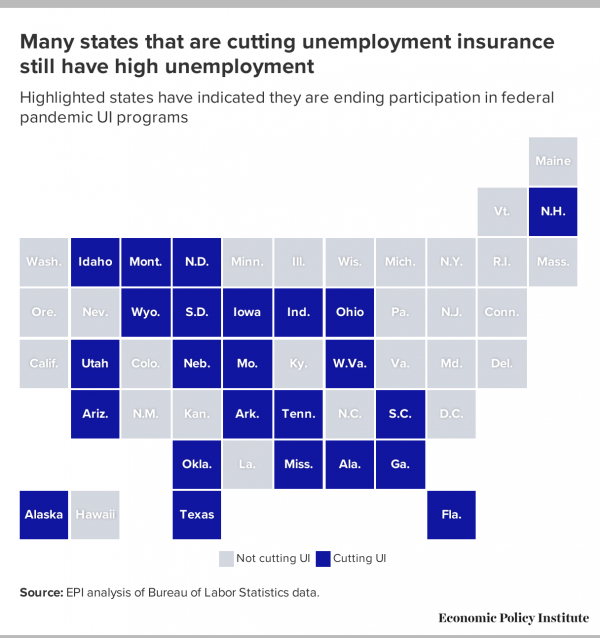

Republican governors in 24 states—including Florida and Nebraska just this week—have indicated they will pull out from the federal unemployment insurance (UI) programs created at the start of the pandemic. Some states are ending participation in all federal pandemic UI programs, others only some of the federal supports. These actions are dangerously shortsighted.

UI provides a lifeline to workers unable to find suitable jobs, giving them time to find work that matches their skills and pays a decent wage. Moreover, the money provided through these entirely federally funded programs bolsters consumer demand and business activity in local economies, helping to speed the recovery. In many states, these federal UI programs are providing the bulk of all unemployment benefits to jobless workers. By cutting off these programs—which currently provide an extra $300 in weekly benefits, allow workers who have exhausted traditional UI to continue receiving benefits, and expand eligibility to workers typically not included in existing UI programs—governors are weakening their states' potential economic growth.

Further, the most recent national jobs and unemployment data show that the country has not yet recovered from the COVID-19 recession. In April, the country was still down 8.2 million jobs from before the pandemic, and down between 9 and 11 million jobs since then if you factor in the jobs the economy should have added to keep up with growth in the working-age population over the past year.

With an official unemployment rate of 6.1%, there are nearly 10 million people actively looking for work and unable to find it. These estimates understate the true level of weakness in the labor market as many people have exited the labor force since the COVID-19 shock began, but would likely rejoin if jobs were available, and others are still awaiting recall from "temporary" layoffs. The country is simply not at a place yet where states should be cutting off supports to unemployed workers.

April state jobs and unemployment data released last Friday show that in many of the states that are cutting unemployment programs, labor market conditions are not much stronger than the national picture. Figure A shows the states that have indicated they will be cutting support for jobless workers. In four of these states, the unemployment rate in April was higher than the national average: Arizona (6.7%), Alaska (6.7%), Texas (6.7%), and Mississippi (6.2%). In another four states, the official unemployment rate was still 5% or above: West Virginia (5.8%), Wyoming (5.4%), South Carolina (5.0%), and Tennessee (5.0%).

However, these estimates likely understate the true weakness in these states' labor markets. In seven of the eight states mentioned above, and in 20 of the 24 states cutting UI, labor force participation has fallen since before the pandemic—in some cases, dramatically. The labor force participation rate has fallen by an average of 1.1 percentage points among the states cutting UI, with declines as large as 3.8% in Iowa, 2.1% in Montana, 2.0% in Florida, 1.9% in Nebraska, and 1.8% in Texas. Some of these declines may be the result of jobless workers opting for early retirement, but it is likely that most have given up looking for work in the face of few suitable options, valid concerns about health risks, or a need to provide care to a child or family member.

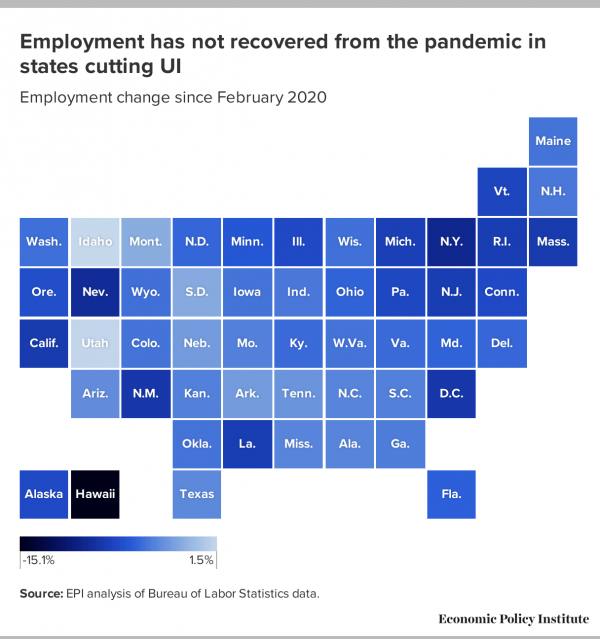

Nearly all the states cutting UI still have significantly fewer jobs than before the pandemic. Employment is down by an average of 3.5% since February 2020 in these states. Factoring in the jobs that these states would have needed to keep up with working-age population growth, employment is 4.8% lower, on average, than where we might expect it to be had there been no recession.1 Data for individual states are available in Figure B. In states cutting UI, the jobs deficit—the difference between the current level of employment in the state and the level we would expect had job growth kept pace with population grown since February 2020—ranges from a low of 12,000 jobs in South Dakota (or 2.8% of April 2021 employment) to 678,000 jobs in Texas (or 5.4% of April 2021 employment).

The most recent decisions by Texas and Florida to cut unemployment benefits are particularly egregious. Texas's unemployment rate is still three percentage points above its pre-pandemic unemployment rate. The state has nearly one million people that are officially unemployed—people actively looking for jobs, but unable to find work. Florida's unemployment rate is 1.5 percentage points above its pre-pandemic rate, with nearly half a million people officially unemployed. Since February 2020, 150,000 people have left the labor force in Texas and nearly 220,000 have exited in Florida.

Claims that the federal UI programs are preventing businesses from finding staff are unsubstantiated by the evidence. Multiple empirical studies have found that expanded unemployment benefits have not meaningfully constrained job growth. In fact, the sectors where generous UI benefits would be most likely to encourage workers to stay out of the workforce would be low-wage sectors, like leisure and hospitality. Yet, that is the sector that experienced the fastest growth in April. The central problem remains a lack of sufficient jobs for everyone that is out of work.

There may be areas where some employers are struggling to staff positions, but the likely obstacle is not overly generous UI benefits—instead it is wage offerings that are too low to make these jobs attractive. As my colleagues Heidi Shierholz and Josh Bivens note:

"Many face-to-face service-sector jobs have become unambiguously worse places to work over the past year. This has in no way been fully restored to the pre-COVID normal, as the coronavirus remains far from fully suppressed. Well-functioning labor markets should account for this degraded quality of jobs by offering higher wages to induce workers back. If enhanced UI benefits and a demand-increasing dose of fiscal stimulus are allowing these higher wages to be quickly offered in the face of supply constraints, then it seems like they're improving labor market efficiency in this regard."

In other words, if some workers are opting to pass on low-paying, potentially dangerous, or otherwise undesirable jobs while they look for something better suited for their skills or circumstances, that's a positive, economy-enhancing feature of a strong UI system.

As the threat from the pandemic fades and businesses resume regular operations, more workers are returning to work and fewer will need to rely on unemployment programs. In every state, the volume of weekly unemployment claims filed has fallen significantly from peaks earlier this year. On average, the total number of initial claims for both regular UI and pandemic unemployment assistance (PUA) have fallen 30% and 38%, respectively, since the beginning of February.2 Continued claims for both programs have fallen similarly.

But those that are still relying on these programs are likely those that need them most—the people having the hardest time finding suitable work or facing significant constraints on their ability to resume working due to care responsibilities, health concerns, or other factors. Cutting off adequate supports to these workers to try to force them to take whatever job might be available—even if it is low-paying, high-risk, not suited to their skills, or incompatible with their responsibilities at home—is cruel and not in the long-term best interest of any state's workers or businesses.

1. Author's calculation using Local Area Unemployment Statistics from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

2. Author's analysis of unemployment insurance data from the U.S. Department of Labor. Values describe the change in the six-month rolling average of claims since the first week of February. Reporting of UI claims for some states is highly volatile, and subject to delays and errant reporting. This range reflects averages having removed a handful of clear outlying values, such as spells of reporting zero claims followed by enormous increases that are likely delayed reporting.

The covid-19 chapter in U.S. economic history is coming to a close more rapidly than almost anyone expected, including me. Within weeks, gross domestic product will reach a new peak, and it is likely to exceed its pre-covid trend line before year's end, as the economy enjoys its fastest year of growth in decades. Job openings are at record levels, and unemployment may well fall below 4 percent in the next 12 months. Wages and productivity growth are increasing.

This is both very good news and a tribute to the aggressive covid-19 containment policies of recent months, as well as to strong fiscal and monetary policies since the onset of the pandemic. Our economy has outperformed those of other industrial countries. U.S. policymakers can take satisfaction from that.

But new conditions require new approaches. Now, the primary risk to the U.S. economy is overheating — and inflation.

Even six months ago, it was reasonable to regard slow growth, high unemployment and deflationary pressures as the predominant risk to the economy. Today, while continuing relief efforts are essential, the focus of our macroeconomic policy needs to change.

Inflationary pressures are mounting from the boost in demand created by the $2 trillion-plus in savings that Americans have accumulated during the pandemic; from large-scale Federal Reserve debt purchases, along with Fed forecasts of essentially zero interest rates into 2024; from roughly $3 trillion in fiscal stimulus passed by Congress; and from soaring stock and real estate prices.

This is not just conjecture. The consumer price index rose at a 7.5 percent annual rate in the first quarter, and inflation expectations jumped at the fastest rate since inflation indexed bonds were introduced a generation ago. Already, consumer prices have risen almost as much as the Fed predicted for the whole year.

"We are seeing very substantial inflation," Warren Buffett recently observed in remarks typical of business leaders throughout the country. "We are raising prices. People are raising prices to us, and it's being accepted."

Fed and Biden administration officials are entirely correct in pointing out that some of that inflation, such as last month's run-up in used-car prices, is transitory. But not everything we are seeing is likely to be temporary. A variety of factors suggests that inflation may yet accelerate — including further price pressures as demand growth outstrips supply growth; rising materials costs and diminished inventories; higher home prices that have so far not been reflected at all in official price indexes; and the impact of inflation expectations on purchasing behavior.

Higher minimum wages, strengthened unions, increased employee benefits and strengthened regulation are all desirable, but they, too, all push up business costs and prices.

It is possible that the Fed could contain inflationary pressures by raising interest rates without damaging the economy. But in the current environment, where markets around the world have been primed to believe that rates will remain very low for the foreseeable future, that will be very difficult, especially given the Fed's new commitment to wait until sustained inflation is apparent before acting. The history here is not encouraging. Every time the Fed has hit the brakes hard enough to slow growth meaningfully, the economy has gone into recession.

How much does it matter whether inflation accelerates? In general, increases in inflation disproportionately hurt the poor and are associated with reductions in trust in government. Progressives might consider the role that inflation played in electing Richard M. Nixon in 1968 and Ronald Reagan in 1980.

Jason Furman, chairman of President Barack Obama's Council of Economic Advisers, recently said that the American Rescue Plan is definitely "too big for the moment," stating: "I don't know of any economist that was recommending something the size of what was done." Excessive stimulus driven by political considerations was a consequential policy error that would be tragically compounded if valid concerns about the economy overheating prevented Congress from making the types of necessary public investments that are the focus of President Biden's Jobs and Families Plans.

So how best can we contain overheating risks and promote sustainable growth while also making necessary investments in infrastructure, greening the economy and helping low- and middle-income families?

First, starting at the Fed, policymakers need to help contain inflation expectations and reduce the risk of a major contractionary shock by explicitly recognizing that overheating, and not excessive slack, is the predominant near-term risk for the economy. Tightening is likely to be necessary, and it is critical to set the stage for that delicate process. Meanwhile, the administration needs to continue to respect the independence of the Fed as it changes course. Clear statements that the United States desires a strong dollar will also be helpful in anchoring inflation expectations.

Second, policies toward workers should be aimed at the labor shortage that is our current reality. Unemployment benefits enabling workers to earn more by not working than working should surely be allowed to run out in September; in some parts of the country they should end sooner. Re-employment bonuses should be considered, and a major focus should be on promoting mobility and training workers for occupations where labor is short. Where "made-in-America" requirements exacerbate labor shortages and raise prices, they should be reconsidered.

Third, it is essential to make long-term public investments to increase productivity and enable more people to work. It would be a grave error to cut back excessively on public-investment ambitions out of inflation concerns. That is not because of the immediate jobs they create, but because of the long-term increases they generate in productive potential, sustainability and inclusivity. But where possible, infrastructure investments should be financed by reprogramming of Rescue Plan funds, such as those now being used by some states to finance tax cuts. Additionally, current spending financed by future taxes might further stimulate an already overheated economy. The opposite — revenue increases ahead of spending, or at least parallel to spending — can ensure more sustainable growth.

The winding down of the covid-19 crisis provides a historic opportunity for taking the next step toward providing for all Americans in an ever more effective and inclusive way. But to avoid squandering the opportunity, policymakers need to accept economic reality. The moment has come to move past emergency policies and fight for our country's long-term future.

|

Stocks are expected to fall for a fourth day.

Joshua Harris will step down as one of Apollo's top executives.

Ford's base model electric F-150 will cost $40,000 and can go 230 miles on one charge.

Cinemas are ready to fill up their seats again. Will audiences follow?

A steel plant in Hefei, China. In recent weeks expectations of a global economic rebound have pushed up the price of iron ore, a key ingredient, although futures slipped lower Thursday.Credit...Jianan Yu/Reuters

A steel plant in Hefei, China. In recent weeks expectations of a global economic rebound have pushed up the price of iron ore, a key ingredient, although futures slipped lower Thursday.Credit...Jianan Yu/Reuters

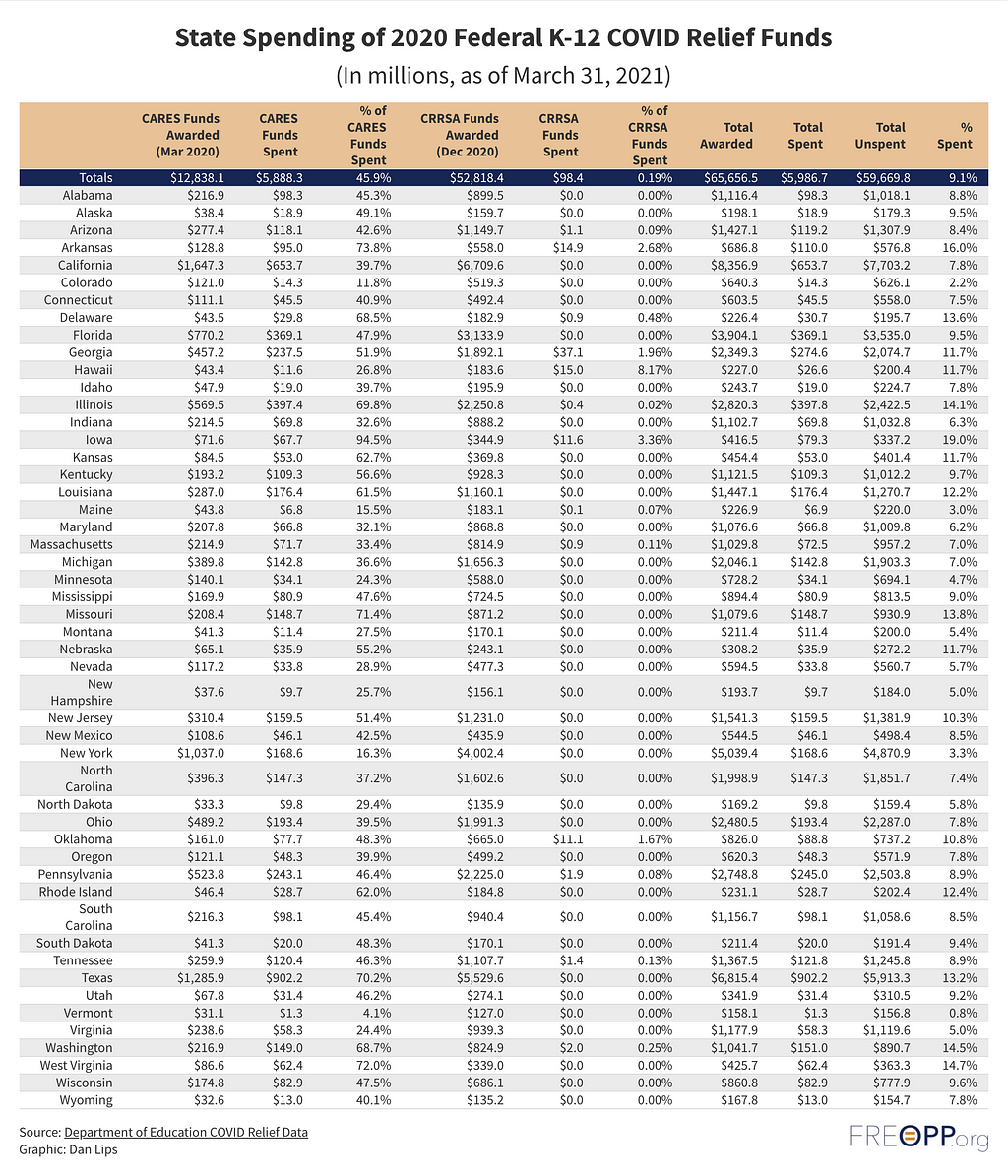

More than one year into the pandemic, state departments of education have spent just a fraction of the nearly $190 billion in emergency K-12 education aid provided by Congress.

As of March 31st, states had only spent $6 billion of the $65.7 billion in Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds provided by Congress in 2020, according to U.S. Department of Education data. This includes $12.8 billion through the CARES Act and $52.8 billion from the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations (CRRSA) Act, which became law in December. The below table provides a breakdown of state expenditures.

The 2021 American Rescue Plan included another $122.8 billion for ESSER funds. The Department of Education announced state allocations of this new funding in March. Based on what has been spent as of March 31st and the additional spending included in the American Rescue Plan, state departments of education have more than $180 billion in emergency funds available. The Department of Education has not begun tracking whether states have spent these funds.

President Joe Biden has proposed additional spending increases for K-12 public education. The American Jobs Plan calls for $100 billion to "upgrade and build new public schools," through direct federal grants and bonds. The American Families Plan proposes $9 billion in funding for American teachers to address shortages, improve training, and increase diversity, $17 billion to expand the national free and reduced school lunch program, and a $1 billion healthy food demonstration project for participating schools.

But experience over the last year suggests that state public education systems are unlikely to spend additional funds in the short run to help children. For example, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office analyzed the American Rescue Plan and projected that $90 billion of the emergency ESSER funds would be spent between 2023 and 2028. The Department of Education data tracking state expenditures of ESSER funds through March 31st shows that, on average, state departments of education have spent less than half of the funds Congress appropriated in March 2020.

Rather than providing more than $100 billion in new funding to state departments of education that already have at least $180 billion in ESSER funds still available, Congress and state policymakers should be focused on using available funds to immediately help students recover from pandemic related learning losses and improve their learning opportunities moving forward. A promising strategy to address both needs is to provide funding directly to disadvantaged students through government-funded education savings account (ESA) programs to help parents pay for school tuition, tutoring, summer school and other educational enrichment services for their children. Seven states currently have active state-funded ESA programs.

$180 Billion of K-12 COVID Relief Funds Are Still Unspent was originally published in FREOPP.org on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.