http://www.shanghaidaily.com/world/US-facing-an-epic-catastrophe-of-evictions-and-homelessness/shdaily.shtml

-- via my feedly newsfeed

When studying urban economics, a common starting point is to make the obvious observation that economic activity does not have an even geographic distribution. Instead, it clusters in metropolitan areas. To put it another way, even with higher real estate costs, higher wages and prices, traffic congestion, pollution, and crime, businesses find it economically worthwhile to locate in urban areas. For such firms, there must be some offsetting productivity benefit. The Summer 2020 issue of the Journal of Economic Perspectives includes a four paper symposium on "Productivity Advantages of Cities."

While urban economists broadly agree on the magnitude of the productivity benefits of density, the evidence distinguishing between possible sources is less solid. Duranton and Puga (2004) classify the mechanisms into three broad classes. First, a larger market allows for a more efficient sharing of local infrastructure, a variety of intermediate input suppliers, or a pool of workers. Second, a larger market also allows for better matching between employers and employees, or buyers and suppliers. Finally, a larger market can also facilitate learning, by facilitating the transmission and accumulation of skills or by promoting the development and adoption of new technologies and business practices.They also point out that these "agglomeration economies" at some point can be outweighed by costs of density like land prices, housing prices, transport costs, and congestion.

Theory has long hypothesized that as population and density increase in a city, its benefits initially accumulate faster, but eventually, its costs dominate (Henderson 1974). Fujita and Thisse (2013) call this the "fundamental trade-off of spatial economics," because it explains both the existence of cities and their finite sizes. However, compared to research on benefits of density, there is a paucity of research on its costs, which Glaeser (2011) dubbed the "demons of density."Rosenthal and Strange dig into some of the productivity advantages of density, and discuss the evidence that the gains of economic activity by being grouped together operate at many levels. For example, if one looks at a certain region, it's not just that economic activity is concentrated within the metropolitan area. In addition, there will be pockets of increased density within the overall urban area, like the Wall Street area in New York. And even within those pockets of higher density, there will be geographic concentrations of specific kinds of firms--like financial or legal or advertising firms--that are bunched within a few blocks or even on different floors in the same buildings. At all of these different levels, there is evidence of productivity gains from being grouped together. They write:

Agglomeration effects operate at various levels of spatial aggregation, including regional, metropolitan, and neighborhood scales. In fact, there is also evidence that agglomeration effects operate below the neighborhood level, including within buildings and organizations. Although agglomeration effects can extend over broad distances, they also attenuate, with nearby activity exerting the strongest effect on productivity.For the last few months, the density of workplaces in the US economy has dramatically diminished. Whatever the productivity benefits of density in cities, concerns over the pandemic and then also about prevalence of crime and rioting are causing firms and workers to push back against density. Moreover, the different dimensions of density can reinforce each other: that is, a city with lots of residents and workers will also tend to have more option for shopping, restaurants, and entertainment, which in turn makes the city a more attractive destination for residents and workers. Conversely, when many workers shift to telecommuting and many residents are trying to stay home to the extent possible, the firms that offer shopping, restaurants, and entertainment are going to suffer.

Duranton and Puga point out that over time, these kinds of changes and cycles in urban areas are not new. They write:

[W]hat will be the long-run consequences of this virus for our densest cities? Pandemics have hit cities the hardest for centuries, and cities have adapted and been shaped by them—from investments in water and sewage systems to prevent cholera, to urban planning to reduce overcrowding and improve air circulation and access to sunlight in response to tuberculosis. Maybe temporary social distancing measures will also leave a permanent footprint on cities—for instance, in the form of more space for pedestrians and bicycles or a gain of outdoor versus indoor leisure environments. But the idea that this pandemic will change cities forever is likely an overstretch. Cities are full of inertia and this crisis has stressed both the costs and benefits of density. Confinement is forcing us to see both the advantages and the great limitations of online meetings relative to the more subtle and unplanned in-person exchanges. It has made us realize that many tasks are impossible to do from home. At schools and universities, the haphazard transition to online courses may speed up their development, or it may delay it as many students have become frustrated by losing aspects of a full educational experience. For a while, some people may try to avoid dense cities for fear of contagion, but others may be drawn to them seeking work opportunities in difficult times.

They may turn out to be correct, especially if a trustworthy and effective coronavirus vaccine emerges. Maybe I've just got a case of the 2020 blues today, but I find that I'm less optimistic. It feels to me as if our society is jamming a huge amount of change into a short time. Just in economic terms, for example, there have been conversations about the future of telecommuting, telemedicine, and distance learning for decades--but now we are leaping ahead with all of these changes all at once. I don't expect metropolitan areas to go away, but there may be substantial shifts within a given urban area in what characteristics people desire in their living arrangements, the location of where they work, the mixture of jobs and industries, how people relax, and how often they are willing to mix with a crowd. At present many households and firms are still cobbling together temporary arrangements--or at least arrangements that are intended to be temporary. But some proportion of that temporary is likely to have long-lasting and disruptive effects.

Last week 1.3 million workers applied for unemployment insurance (UI) benefits. More specifically, 832,000 applied for regular state unemployment insurance (not seasonally adjusted), and 489,000 applied for Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA). Some headlines this morning are saying there were 963,000 UI claims last week, but that's not the right number to use. Instead, our measure includes PUA, the federal program that is supporting millions of workers who are not eligible for regular UI, such as the self-employed. We also use not seasonally adjusted data, because the way Department of Labor (DOL) does seasonal adjustments (which is useful in normal times) distorts the data right now.

Astonishingly high numbers of workers continue to claim UI, and we are still 12.9 million jobs short of February employment levels. And yet, Senate Republicans allowed the across-the-board $600 increase in weekly UI benefits—the most effective economic policy crisis response so far—to expire.

In an unserious move of political theater, the Trump administration has proposed starting up an entirely new system of restoring wages to laid-off workers through executive order (EO). But even in their EO wishlist, the Trump administration would slash the federal contribution to enhanced unemployment benefits in half, to $300. This inaction and ongoing uncertainty is causing significant economic pain for workers who have lost their job during the pandemic and their families. It also causes an administrative hassle for state agencies that have already struggled immensely to process the huge number of claims early in the pandemic and implement the new UI protections in the CARES Act. Since the states with the least stable UI systems also have the highest populations of Black and Latinx people, existing inequalities will likely deepen even further by both the cutoff of supplementary benefits and the increased chaos introduced by having presidential EOs pretend to stand in for the legislative action that is needed.

Cutting UI benefits is directly harmful not just to the individual workers who rely on them, but to the economy as a whole. The additional $600 in benefits allowed for a large amount of spending, sustaining these workers' effective demand for goods and services even in the face of joblessness. If the Trump administration gets their way and these benefits are cut in half, it would cause such a large drop in spending that it would cost us 2.6 million jobs over the next year.

During the pandemic, Black and brown communities have suffered disproportionately on the front lines and in the unemployment lines. Black women in essential occupations are paid less than white men for doing the same vital work. At the same time, Black and Hispanic workers have seen higher unemployment rates than white workers in this recession, meaning they are disproportionately harmed by the cut to UI benefits. These communities, and Black women in particular, should be centered in policy solutions.

Some have argued that the additional benefits create a disincentive for workers to return to the workforce. However, studies—including one conducted by Yale economists—found no evidence that recipients of more generous benefits were less likely to return to work. Further, there are millions more unemployed workers than job openings, meaning millions will remain jobless no matter what they do. In short, the primary constraint on job growth in the near term is depressed demand for workers, not workers' incentives. In any case, our top priority as a country should be protecting the health and safety of workers and our broader communities by paying workers to stay home when they feel safer not working in person (or feel their families' welfare is improved by them not working in the pandemic), whether that means working from home some or all of the time, using paid leave, or claiming UI benefits. The recent spikes in coronavirus cases across the country—and subsequent re-shuttering of certain businesses—show the devastating costs of reopening economic sectors prematurely.

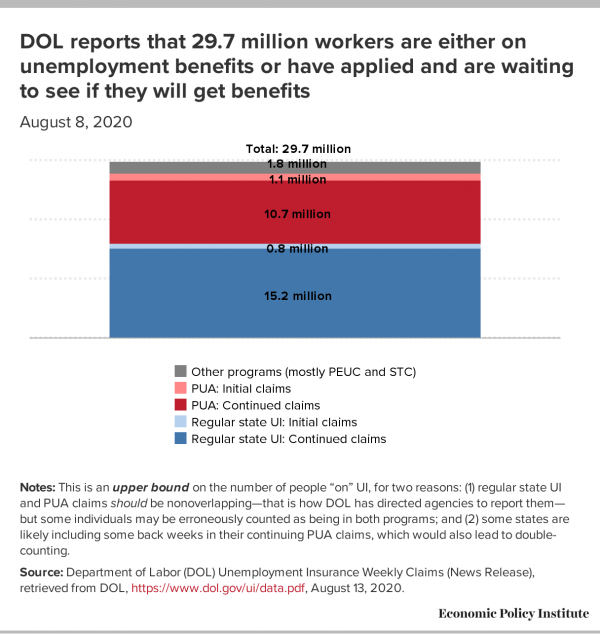

Figure A combines the most recent data on both continuing claims and initial claims to get a measure of the total number of people either receiving or planning to receive unemployment benefits as of August 8. DOL numbers indicate that right now, 29.7 million workers are either on unemployment benefits, have been approved and are waiting for benefits, or have applied recently and are waiting to get approved. But importantly, Figure A provides an upper bound on the number of people "on" UI, for two reasons: (1) Some individuals may be being counted twice. Regular state UI and PUA claims should be non-overlapping—that is how DOL has directed state agencies to report them—but some individuals may be erroneously counted as being in both programs; (2) Some states are likely including some back weeks in their continuing PUA claims, which would also lead to double counting (the discussion around Figure 3 in this paper covers this issue well).

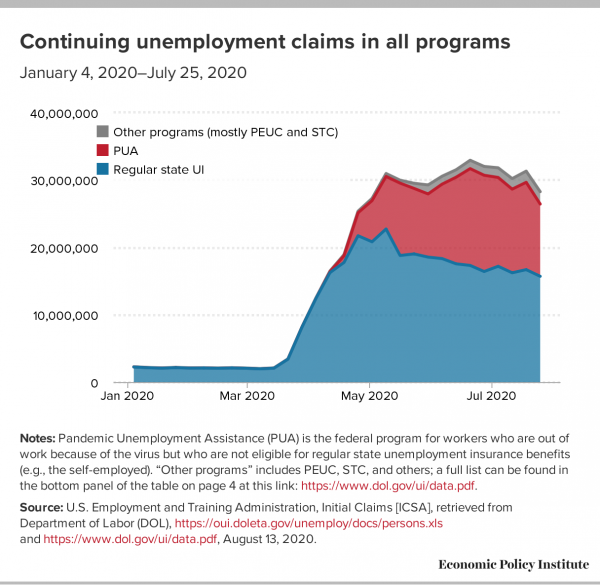

Figure B shows continuing claims in all programs over time (the latest data are for July 25). Continuing claims are 26.6 million above where they were a year ago. However, the above caveat about potential double counting applies here too, which means the trends over time should be interpreted with caution.

As the pandemic drags on, many workers are facing long-term joblessness. The number of people claiming Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC), the 13 additional weeks of benefits available to workers who have exhausted the 26 weeks of regular benefits, increased by 67,000 during the week of July 25. However, it is clear that even this 13 week extension is not enough to meet the needs of many workers, and policymakers should extend it even further. As evidence of this, the Extended Benefits program, which provides an additional 13 weeks of benefits after PEUC, had a 56,000 increase in claimants during the week of July 25. There are now 126,000 workers claiming Extended Benefits, the highest number so far this recession, and every state meets the high unemployment threshold that is required for these benefits to kick into effect. Congress must not allow another crucial provision to lapse.

It's understandable. People don't want to be accused of alarmism and making a bad situation worse. But this reticence is self-defeating and ahistoric. It minimizes the gravity of the crisis and ignores comparisons with the 1930s and the 19th century. That matters. If the hordes of party-goers had understood the pandemic's true dangers, perhaps they would have been more responsible in practicing social distancing.

Even after the July jobs report, when the unemployment rate fell from June's 11.1 percent to 10.2 percent, the labor market remains dismal. Here are comparisons with February, the last month before the pandemic was fully reflected in job statistics: The number of employed fell by 15.2 million; the unemployed rose by 10.6 million; and those not in the labor force increased by 5.5 million.

"The nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were filled with depressions," write the husband-and-wife Reinharts. Among economists, they are heavy hitters. She is a Harvard professor, on leave and serving as the chief economist of the World Bank; he was a top official at the Federal Reserve and is now chief economist at BNY Mellon.

What's clear is that the Pandemic Depression resembles the Great Depression of the 1930s more than it does the typical post-World War II recession. To simplify slightly: The typical postwar slump occurred when the Fed raised interest rates to reduce consumer price inflation. They lowered rates to stimulate growth.

By contrast, both the Great Recession and the Pandemic Depression had other causes. The Great Recession reflected runaway real estate and financial speculation and their adverse effects on the banking system. The Pandemic Depression occurred when infection fears and government mandates led to layoffs and an implosion of consumer spending.

The collateral damage has been huge. Small businesses accounted for 47 percent of private-sector jobs in 2016, estimates the Small Business Administration. Many have failed or will fail because they lacked the cash to survive a lengthy shut down. In a new study, economist Robert Fairlie of the University of California at Santa Cruz reports an 8 percent drop in the number of small businesses from February to June. Among African Americans, the decline was 19 percent; among Hispanics, 10 percent.

In one respect, the Reinharts have underestimated the parallels between the today's depression and its 1930s predecessor. What was unnerving about the Great Depression is that its causes were not understood at the time. People feared what they could not explain. The consensus belief was that business downturns were self-correcting. Surplus inventories would be sold; inefficient firms would fail; wages would drop. The survivors of this brutal process would then be in a position to expand.

This view rationalized patience and passivity. Just wait; things will get better. When they didn't, anxiety and discontent mounted. There was an intellectual void. Modern scholarship has filled the void. If — at the time — government had been more aggressive, preventing bank failures and embracing larger budget deficits to stimulate spending, the economy wouldn't have collapsed. The Great Depression wouldn't have been so great.

Something similar is occurring today. The interaction between medicine and economics often baffles. Is this a health-care crisis or an economic crisis? Before the New Deal in the 1930s, national leaders followed the conventional wisdom of the day — doing little. Similarly, leaders now are following today's conventional wisdom, which is to spend lavishly. Will this work or will the explosion of government debt ultimately create a new sort of crisis?

The language of the past increasingly fits the conditions of the present. The many busts of the 19th century have long been referred to as "depressions" — for example, in the late 1830s, the 1870s and the 1890s. The accepted reality at the time was that mere mortals had little control over economic events. We thought we had moved on, but maybe we haven't.

The implications for the economic outlook are daunting. In their essay, the Reinharts distinguish between an economic "rebound" and an economic "recovery." A rebound implies positive economic growth, which they consider likely, but not enough to achieve full recovery. This would equal or surpass the economy's performance before the pandemic. How long would that take? Five years is the Reinharts' best guess — and maybe more.