Sam Pryke examines the view that the Covid19 pandemic is further weakening globalisation and finds that this is not the case. In some respects, it is extending it.

Globalisation was in trouble for some time before Covid19 according to commentators. The last 3 months have apparently seen it's impetus further weakened. But, although the current pandemic may see aspects of global interconnection reconfigured, talk of its demise is much exaggerated.

Pundits have engaged in talk of 'de-globalisation', even 'the end of globalisation' since 2016, whilst gloomy forecasts, often from supporters of free markets, go all the way back to the financial crash of 2008. That was termed by some, notably the then British PM Gordon Brown, as the first crisis of globalisation. Analysts argued that the failure of the experiment in free market capitalism, one that had come to dominate government policy for 3 decades through the ideological guise that 'there is no alternative', would give rise to various forms of protectionism. This didn't really happen. There was no systematic attempt by governments to pull apart the integration of economies. Instead, globalisation on most, if not all, measures regained the levels attained in 2007 by 2011/12 - and then grew further. International trade is the most commonly used indicator of globalisation. In 2018, more goods were traded around the world than ever before. The last DHL survey found that in 2017 the volume of worldwide flows of finance, commodities, information and people, therefore a more rounded assessment, were at their highest ever levels.

Why then a chorus of voices saying that globalisation is in retreat? Central has been the rise in nationalist (or populist) movements and leaders: BREXIT and then Johnson in Britain, Trump in the USA, Xi Jinping in China, Bolsonaro in Brazil and Modi in India are five of the best known examples. Of these leaders, only Trump is explicit in his rejection of globalisation – 'Americanism not globalism' was a campaign cry as he announced his candidacy for the Republican Party in 2015 – and has backed his words by tariffs on more than $360bn (£268bn) of Chinese goods. China has retaliated with tariffs on more than $110bn of US products. But all are sceptical of aspects of globalisation, certainly any perceived diminution of state power. Besides nationalism, commentators have also pointed to de-globalisation through the 'reshoring' of investments of multinational companies and the implications of robots fitted with artificial intelligence - specifically, their potential to do the work that large numbers of immigrants do because domestic populations won't.

If received opinion was that globalisation was already in trouble, the spread of Covid19 has prompted numerous claims that the pandemic will do further long term damage. The gist of some comment has been to underline what is obvious: the effort to prevent the spread of the virus, something that travelled through global networks, has reasserted the enormous power of nation states. Leaving aside simplistic dichotomies between states and global actors (e.g. multinational companies) and arenas (world markets), negative state power has been evident in their ability to prevent people from moving between and within countries for work or leisure, and to close down sections of economies. And in their positive power to pay workers whose employers have been compulsorily closed, to boost domestic economies through massive financial injections and to provide health care for those who have contracted the virus. In the USA, the federal state tried to stop some companies, notably the PPE manufacturer 3M, from exporting face masks. This exceptional governance and policy (that has of course resulted in $ trillions of additional debt) has underlined what has always been obvious: states have the real power in the world and businesses have always been reliant on them – especially at times of crisis. Books of yesteryear that depicted a 'hyperglobalist' world like The End of the Nation State and The World is Flat always were rather silly.

Besides the obvious reality, there are other arguments why coronavirus is 'killing globalisation as we know it'. Phillipe Legrain, a writer who popularised the case that globalisation has been broadly a positive phenomenon through greater cultural diversity and rising international prosperity, argued at the beginning of March that the pandemic was likely to result in three outcomes. First, it will see streamlined supply chains – and not just in respect to pharmaceutical and food supply. About half of world trade is between contractors within supply chains. The iPhone is only one example. Apple has simplified it in recent years, but still has 8 suppliers (who in turn outsource) of components to its Taiwanese manufacturer, Foxconn. Foxconn's workers assemble the mobile device in Shenzhen, China, before distribution worldwide for sale. Legrain thinks that companies will increasingly seek to shift investment from China (albeit usually elsewhere within Asia) and utilise where possible robotic production within their nation state. Second, he speculates that the temporary international travel and immigration bans governments have imposed to prevent the spread of the virus will not be removed wholesale if and when the virus is eliminated. This will have the effect of reducing international business mobility, something that had been projected to rise to $1.3 trillion worth of flights, hotel bookings etc. in 2020. Instead, executives will continue to use the video communication forms they have turned to during the lockdown. Third, Legrain says that the pandemic will boost the nationalism and xenophobia referred to above. As usual, Trump is the best (or worst) example. Amongst other things, for a time he called Covid19 the 'Chinese virus' in White House press conferences, leading to attacks on American Asians and contributing to what has been termed a new cold war between the USA and China. A greivance ridden American nationalism is likely to be central to his campaign for re-election in November.

'It's difficult to make predictions, especially about the future', can be a sound approach in an unpredictable world. But it is possible to say certain things about what is likely to happen based on what is occurring now and what took place in the past - even with the uncertainty surrounding Coronavirus, i.e. possible mutations, a vaccine(s) etc. The following points don't constitute a future global scenario. But, taken together, they suggest that, whilst the pandemic may give rise to significant change, we need to be sceptical about talk of the death of globalisation now – as we should have been more critical of exaggerated claims of its extent in the past.

First, even the most pessimistic estimates of global trade only predict that it will fall to the levels of 2010. The integration of national economies into world markets over the last 60 years through the export of goods and services, constituting a third of all economic activity, is highly unlikely to come to an end because of the pandemic. Attempted withdrawal by governments from the world economy into self-contained national units, autarchy, would see economic Armageddon. Foreign direct investment will fall sharply but is still estimated to be in excess of $1 trillion this year. Moreover, FDI tends to be volatile. It fell by 38 per cent in 2010 but rebounded to above the previous high within four years. The projected decline this year of 90 per cent in international flights carrying tourists, business travellers and migrants is dramatic, but this is after tremendous growth. Even with such a decline, the number of flyers will be higher than in 2003.

Besides the empirical evidence, there is a more basic reason why the pandemic is unlikely to see the end of globalisation. That's because its driving force, capitalism, is inherently global. As Karl Marx, the first great analyst of globalisation, put it more than 170 years ago, 'The need of a constantly expanding market for its products chases the bourgeoisie [the capitalist class] over the entire surface of the globe. It must nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connexions everywhere'. Capitalism faces constraints of politics and geography but in their search for profit, capitalists will always seek to evade and reduce them. Moreover, capitalists are inclined to use the chaos generated by a crisis to remove obstacles to greater income, something referred to as 'disaster capitalism'. Currently employers, university VCs amongst them, are dispensing with the normal procedures that pertain and cynically forcing through structural changes within their organisations to cut costs. With the possibilities offered by enhanced video connectivity, it is inevitable that they are simultaneously investigating the possibility of outsourcing services to global locations where wages are lower. The pandemic is likely to be seen as more than a temporary blip in capitalism's history, but not a great deal more. One thing that would have surprised Marx is capitalism's resilience.

It is possible that some retrenchment of globalisation will take place through greater regionalisation. Most external economic activity (trade, investment, travel) has always taken place in geographic areas, regardless of whether there is a strong regional organisation or not. This year, the majority of trade of Asian countries will take place within others in that region. Much of the increase in international migration in recent history has taken place because of the numbers of people moving intra Asian. In the only part of the world where there is an effective regional organisation, Europe, the EU's future was questioned as member states responded individually to the threat of the virus. Since then, the EU has partially overcome the opposition of key member states to put in place a modest European wide economic stimulus package for the post pandemic period. The plans afoot to mutualise sovereign debt within the Eurozone would see a considerable advance in economic and monetary union. Borders are beginning to open again across the Schengen zone. It could be that post pandemic there's further regional integration in Europe (despite BREXIT), in Asia and elsewhere.

A different type of reason to be sceptical of over blown claims about the impact of Covid19 is, as indicated, some forms of global communication (or culture) have increased their reach during the pandemic lockdown. A recent FT survey of the top 100 corporate beneficiaries reveals that the winners (besides a small number of giant pharmaceutical firms involved in vaccines) are home shopping companies, technology firms selling computing, software, games and video and those specialising in e commerce and online payment, i.e. the companies that have been at the cusp of globalisation in recent years. The companies are predominately American, but 3 Chinese tech firms feature in the top 20. Predictably, Amazon's market capital increase of $410 billion easily leads Microsoft in second place, making its founder, Jeff Bezos, another $24 billion richer as of mid-April. The video company that many quickly discovered after the lockdown for work and leisure, Zoom, has seen its stock value exceed the declining worth of the 7 biggest airlines put together. It is in itself an interesting example of globalisation. Zoom's owner, Eric Yuan, was born and raised in China, migrating to Silicon Valley, California, where he subsequently launched the business. His supposed 'dual loyalty' was raised recently when Zoom gave into the demands of Chinese censors to block the accounts of dissidents involved in online commemoration of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre. More likely reasons are that that Zoom (along with the equally compliant Apple and Google) seeks access to Chinese markets, and conducts a considerable amount of its R&D in China – further indication that its economy is no longer just a giant low wage assembly plant.

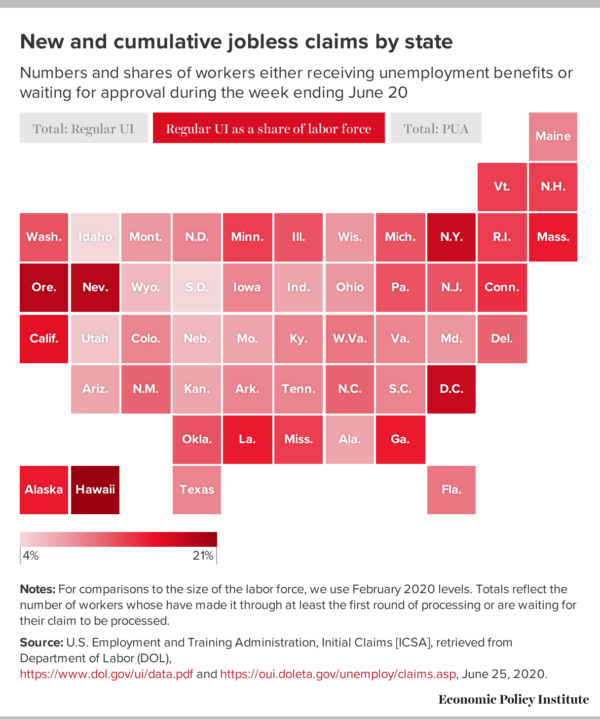

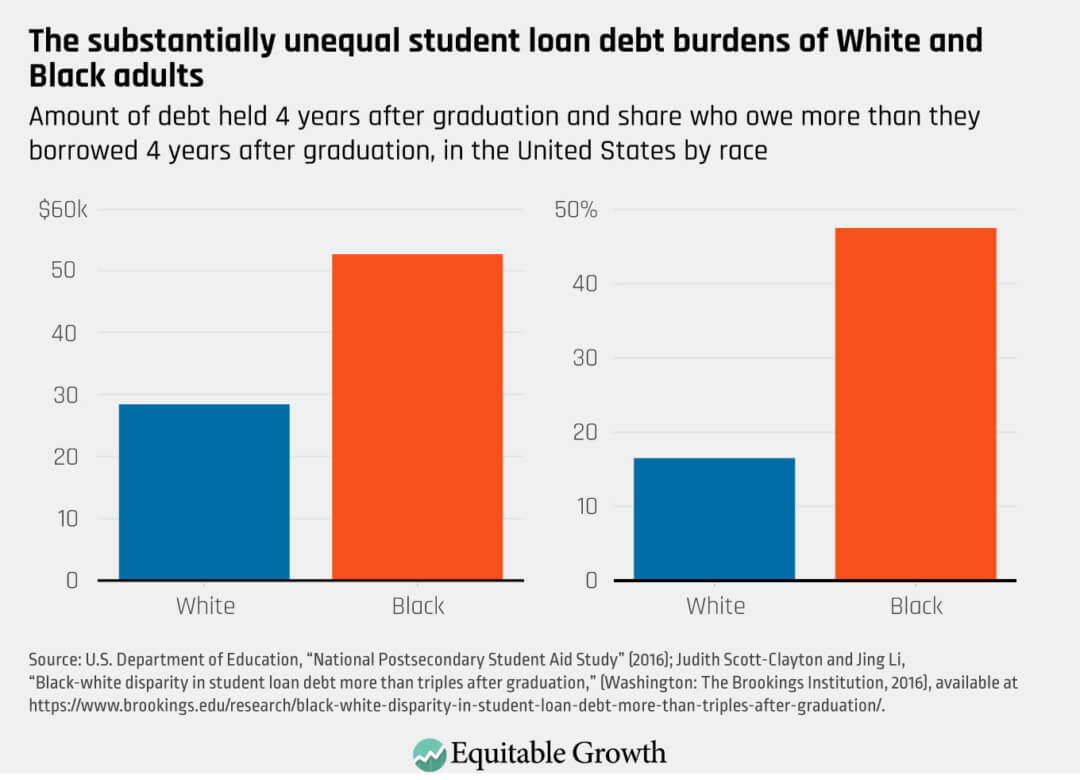

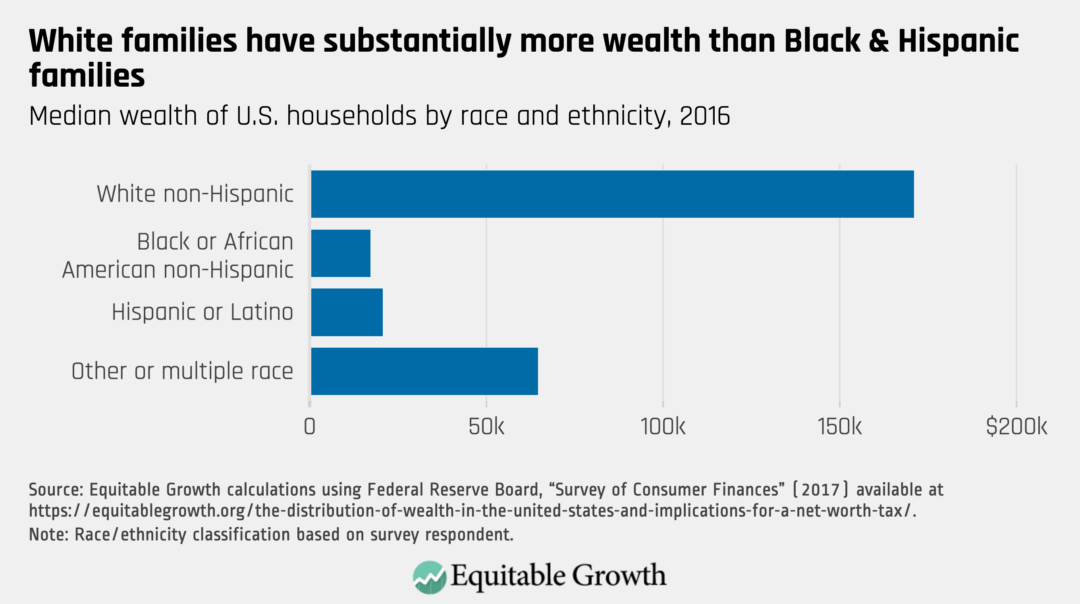

Finally, the pandemic has seen the globalisation of protest. This aspect of globalisation has been there since the term became a buzz word in the late 1990s. Misleadingly, the protestors at the meetings of international leaders were dubbed the 'anti-globalisation' movement by the media. Their concerns were global inequality, injustice and environmental destruction. The way in which the virus has disproportionately impacted on poorer and more vulnerable sections of populations – BAME communities in Britain, internal migrants in India, indigenous peoples in Brazil – is only a brutal revelation of those inequalities. The response of Jair Bolsanaro, the Brazilian president, of 'So what?' when asked about the mounting death toll seemed to sum up the indifference of rulers. However, the issue which has sparked worldwide protest wasn't directly related to health inequality, but racial injustice: the murder of George Floyd, an unemployed African American, by the white policeman, Derek Chauvin, now charged with murder. It's not like killings of people of colour by the police haven't taken place in the USA (and elsewhere) before, or that video footage hasn't been circulated on social media. The Black Lives Matter movement started in 2013 after the acquittal of a police officer for the killing of Trayvon Martin. What was different this time was the way the lockdown concentrated the attention of a worldwide audience on the video of 8 minutes and 46 seconds as George pleaded for his life as it was snuffed out.

As is well known, the event triggered not just demonstrations – physical and virtual - of overwhelmingly young, Black and white people across the US but the world, notably in Britain and France. These have had some tangible results in America. When there were protests over police brutality in America in 1967 they responded by shooting dead 43 people. The fact that the eyes of the world were trained on the unfolding events today meant that such a state response wasn't possible. Black Lives Matter protests surely presage future worldwide campaigns over a threat of a far greater magnitude than Covid19, one that really does threaten humanity: global warming.

-- via my feedly newsfeed