from Matt Stoller's BIG blog

Today’s monopoly round-up has lots of good and bad news, as usual, after the paywall.

For the week’s focus, I’m going to look at the inability of the U.S. to make what it needs, and the two different approaches unveiled this week to address it. The first approach is Trump’s 25% tariff scheme on automobiles, as well as his April 2nd “liberation day” of trade barriers. And the second is the promotion of a new book called Abundance by Ezra Klein of the New York Times and Derek Thompson of The Atlantic, a revamped version of 1980s-style supply side politics. What do these moments tell us?

Let’s start with the problem of production. Whether good or bad, it’s quite clear at this point that the U.S. has a serious deficit in producing physical things. We all remember nurses wearing trash bags during the pandemic, and the pervasive shortages of key goods. Even today, we have shortages in baby formula and pharmaceuticals, not to mention infrastructure and housing being wildly expensive. Moreover, the U.S. is getting killed globally. The Chinese car industry is going exponential in exports, Airbus is taking market share over Boeing, and the U.S. military is sounding the alarm on production of artillery shells and missiles. If you look at the U.S. trade deficit, it’s a massive trillion dollar plus set of imports over exports.

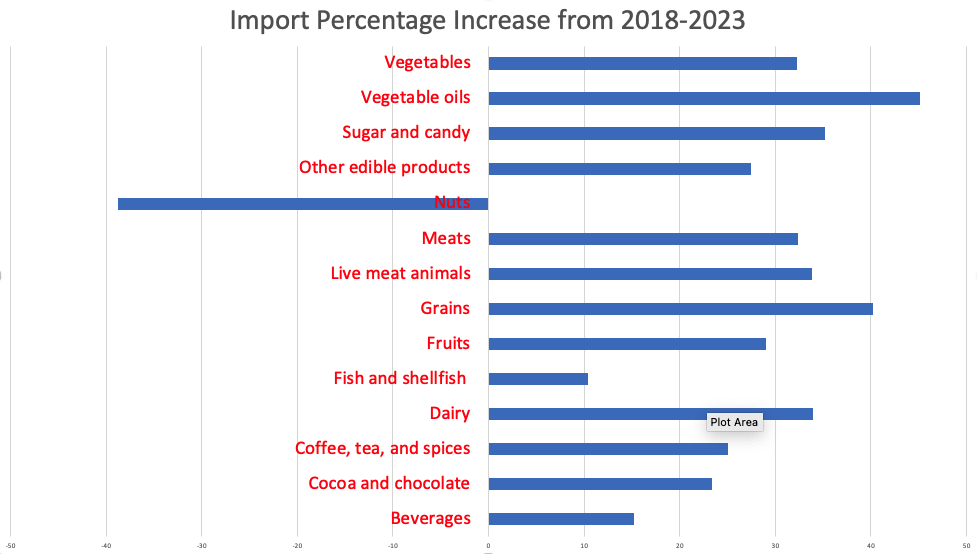

Typically this problem is understood as a manufacturing story, but that’s incomplete. It’s also an agricultural story. In 2022, the U.S., which has the most exceptional farmland in the entire world, began running a trade deficit in food, and now it’s quite significant. Here’s a chart of food import increases since 2018. Except for nuts, the U.S. is becoming dependent on foreign sources of food.

The data is one thing, but I don’t think there’s any way to really understand the problem without talking to people who actually make and sell things. A few weeks ago, we interviewed farmer Jeff Bender, and he talked about how much harder it is to produce milk, vegetables, feedstock, and meat because of monopolistic buyers and suppliers, and the policymakers at a state and Federal level who support them. It’s the same story with Laura Modi, an entrepreneur in baby formula, who also told us about the problems in getting into the market. Same thing with pharmaceuticals, which distributor Tim Ward and pharmacist Benjamin Jolley told us about.

And it’s not just the little guys, either. In a podcast on electric cars, Ford CEO Jim Farley made a fascinating point about why Ford is so behind Tesla and Chinese automakers.

“We farmed out all the modules that control the vehicles to our suppliers because we could bid them against each other, so Bosch would do the body control module, someone else would do the seat control module, someone else would do the engine control module. We have about 150 of these modules with semiconductors all through the car. The problem is the software are all written by you know 150 different companies and they don't talk to each other. So even though it says Ford on the front, I actually have to go to Bosch to get permission to change their seat Control software.

So even if I had a high-speed modem in the vehicle and and I had the ability to write their software, it's actually their IP and I have 150, we call it the loose Confederation of software providers, 150 completely different software programming languages, you know all the structure of the software is different.

Farley says that now Ford has to rebuild everything from scratch. “We're literally writing how the vehicle operates the software to operate the vehicle for the first time ever,” he said.

It’s clear the U.S. has a serious problem in building. Why? And what happened?

The answer is pretty simple. In the 1980s, after 20 years of debate over the U.S.’s roll in the world, we decided that the U.S. shouldn’t make things anymore. We decided to become a ‘service’ economy, focused on design, research, and finance, leaving the grubby work of physical stuff to others. Here’s Washington Post columnist Fareed Zakaria, whose job it is to maintain the conventional wisdom, making the point:

The idea that America should make more things is a seductive one… But it is an image of the past, not the future. The most advanced economies in the world today are almost all dominated by services. Services account for the vast majority of jobs in the world’s richest industrialized countries… America’s distinctive exports to the world are software and software services, entertainment, financial services, and other such intangible things — and in these, the U.S. runs not a trade deficit but a surplus with the rest of the world.

It’s not just Zakaria. In January, Democratic economist Paul Krugman attacked Trump for trying to restore manufacturing, arguing that “people should understand both that we are going to be a service economy no matter what, and that that’s OK: a fixation on manufacturing as the only source of good jobs is generations out of date.”

Even the Biden administration, which did seek to re-shore certain industries, couldn’t control its economists. In 2024, the Biden’s White House Council of Economic Advisors published a blog post explaining that those worrying about physical production were silly, and that U.S. services trade surplus showed how our strategy was working. We specialize in things like finance, services, and “intellectual property, such as patents, trademarks, software and data licenses,” that we design here and collect rents on from abroad. On the other side of the aisle, the pull against production is just as strong. Republican Congressional members, deferential on virtually everything, are beginning to muse on taking tariff power away from Trump.

Wall Street-types are deeply hostile; billionaire Ray Dalio recently said the U.S. can’t make things and should stop trying. Bloomberg’s Joe Weisenthal was puzzled at the very notion of preventing foreign goods from undercutting domestic production.

If the U.S. doesn’t make things, what exactly do we do? What is our national geopolitical strategy? Prior to 1970, it was producing more of everything than anyone else. More food, more cars, more steel, more semiconductors, more technology, more oil. The U.S. was the manufacturing plant for two world wars. But when the U.S. gained financial supremacy over the world in 1945, we became a producer of something far more potentially profitable than mere physical goods - the dollar. It’s much easier to print money than to bend metal.

At first, this dynamic didn’t cause significant political problems, because the government had extensive control over finance. The Fed and Congress made careful choices about who could and couldn’t get credit. Banking was a public business, and policymakers forced lending into sectors that were important, like housing, farming and manufacturing, and blocked lending into speculation. There were extensive capital controls to stop dollars from flowing abroad without government sanction, and states negotiated with each other on capital flows.

For 35 years after World War II, the constituency groups who built the New Deal arrangement had a broad understanding that financial consolidation led to fascism; the hot money flows of the 1920s, in the hands of private bankers, had helped raise the stock market, but also bring Hitler to power and break the world. The things required to make a democratic society, such as well-paid workers, communities, domestic production and investment, a robust educational system, a hearty small business apparatus, lots of small banks and farms, et al, are just not consistent with high stock prices and the consolidation of economic power they imply. Power, they knew, corrupts.

Economists have retroactively given this policy framework a name, “financial repression,” meaning that those who had financial capital were heavily taxed and controlled. While the government prints dollars, there is another group that sought to manage bonds, stocks, and credit instruments, without public checks: Wall Street. And that group, enfeebled during the Great Depression but waiting in the wings, bided their time.

Finally, in the 1970s, a group of people on the right and left, today known as neoliberals, attacked New Deal controls over finance and the corporation as silly. They argued, in an age of “microchips, robots, and computers,” mucking around with making things like t-shirts and steel was foolish.

This argument came into politics through both sides of the aisle. The Reagan administration was run by Wall Street, with men like banker William Simon and Chicago Schooler Robert Bork organizing policy. But it was preceded by Jimmy Carter’s deregulation of shipping, banking, trains, buses, trucking, airlines, energy, and even skiing, and his appointment of Wall Street-friendly Fed Chair Paul Volcker.

In 1980, the Democratic-led Senate Joint Economic Committee published a report titled Plugging in the Supply Side. Lloyd Bentsen, who later became Bill Clinton’s Treasury Secretary during the NAFTA fight, authored it. Everyone from Paul Tsongas, to Gary Hart to Robert Reich bought this frame, as did magazines like The New Republic. By 1980, neoliberalism had become consensus. Ted Kennedy, Jimmy Carter’s ostensibly “liberal” nemesis, fought to go further than Carter in ending rules on airplanes, and Ralph Nader aligned with Citibank on deregulating finance. Many of the unions, with the exception of the Teamsters, bought into deregulation.

The consequences were immediate. The U.S. manufacturing base took a major hit as the trade deficit exploded under Ronald Reagan. Bill Clinton continued and expanded it, focusing on high-technology pursuits and a “Bridge to the 21st Century.” When you think about it, that’s weird. How can a nation keep importing more than it exports, on a permanent basis? Why would trade partners keep sending them stuff? The answer is in the part of the story that the proponents of this model suggest, which is services. One key service the U.S. provides is to operate like a giant global bank. If you are a foreign elite, you can export to the U.S. and use that money to buy safe dollar dollar assets.

Here’s Wharton professor and stock booster Jeremy Siegel, explaining the virtues of a trade deficit.

Suppose an American buys a $40,000 Toyota made in Japan. Toyota has three options for what to do with these dollars. It can buy $40,000 worth of U.S. goods or services, in which case there would be no trade deficit. Or, because it expects the American economy to grow, it can invest $40,000 in U.S. capital—say, the S&P 500 index, U.S. government bonds or American real estate…

This demand for U.S. assets boosted the value of American stocks and bonds and helped fund the country’s growing budget deficit.

U.S. consumers lost jobs, but got cheap stuff. Meanwhile, foreigners got to build out their industrial base and received dollar assets that would probably appreciate. Wall Street made money managing the global flow of dollars, and institutions like the Fed became more important. In fact, appreciation of financial assets became the U.S. strategy.

The Number Go Up Problem

In the 1970s, neoliberals thought that the U.S. should focus on “sunrise” industries, like semiconductors, industrial design, and finance, as opposed to things like steel and cars. Stuff that required large factories, high cost blue collar labor, and pollution, could be done abroad, whereas the high value research would be done in the U.S. Part of that is deregulation of finance, which is by now a well-understood story. There’s a reason Jack Welch, for instance, gradually turned General Electric from a manufacturing colossus to a credit card giant.

But there’s a parallel story in other “capital light” areas. As Erik Peinert noted, there was a revolutionary expansion of intellectual property rights, which foreclosed vast swaths of the public domain. For instance, in 1980 Congress updated the copyright act to include software, paving the way for Microsoft and the modern software industry. In the 1980s, the Supreme Court legalized the patenting of bacteria; later the government legalized the patenting of genetically altered plants, animals, and foods. That’s Monsanto. The Bayh-Dole Act of 1980 transformed universities so they would have a strong incentive to become factories for licensable IP instead of knowledge factories. Semiconductor chips got copyright protection in 1984.

In general, antitrust law around the use of copyrights and patents was relaxed, meaning that corporations, who used to have to build factories to take advantage of their IP or license their IP to all comers, could now selectively control suppliers with patent, trade secrets, and copyright rules. All of these changes were internationalized in the 1990s through trade agreements. The consequences are vast, from Apple being able to “make” iPhones without owning a single factory while controlling millions of non-employees, to the American Medical Association grifting off of a ridiculous copyright of medical billing codes. These were extreme radical shifts, designed to move power from producers to financiers. And they did.

Shifting patents and copyright, deregulating finance, and allowing monopolization led to two things. First, they shifted ownership from workers and business people to Wall Street. Three scholars just published a paper on the distributional effects of these choices.

From 1989 to 2017, the real per capita value of corporate equity increased at a 7.2% annual rate. We estimate that 40% of this increase was attributable to a reallocation of rewards to shareholders in a decelerating economy, primarily at the expense of labor compensation. Economic growth accounted for just 25% of the increase, followed by a lower risk price (21%) and lower interest rates (14%). The period 1952–88 experienced only one-third as much growth in market equity, but economic growth accounted for more than 100% of it.

For instance, Microsoft was among the best-performing stocks of the 1980s and 1990s. Bill Gates became the richest man in the world because of his monopoly control over software, enabled by antitrust policy. His financialization of the industry was deeply costly, foreclosing what had been a vibrant and creative ecosystem and turning it into a shoddy corporatized system of insecure and locked down products. Similarly, when Walmart took over retailing through price discrimination, and the Walton family became worth $434 billion, that was wealth taken from tens of thousands of producers and independent store owners who had their property seized.

Second, financialization makes it harder to produce. Let’s go back to Ford CEO Jim Farley’s comments on how Ford has to get permission to modify software from suppliers for its own vehicles. That’s crazy and very bad for our ability to improve our cars. It’s also a function of law, of copyright stopping the company’s engineers from tinkering.

Corporate strategy in America today is about orchestrating bottlenecks, because if you can create a chokepoint, aka some form of a monopolistic toll booth or restraint of trade, you can charge more money. The U.S. economic strategy, as we learned during Covid, is about creating precisely such bottlenecks. Whether done through copyright, patent, cost of capital, merger, price discrimination, foreclosing a rival from getting access to the market, surveillance, limiting homebuilding by sitting on land, or any other tactic, broadly speaking, all inflating financial assets does is hinder production. That’s the point, withhold supply, increase the price.

But what this mass seizure of property from the middle class, and the destruction of our productive capacity, did was part of our national strategy. When foreigners bought up U.S. dollar assets, more stocks and bonds, there were brief moments when Americans became afraid that, say, the Japanese would dominate our economy. But what ended up happening is that Wall Street created a bunch of American billionaires through financial asset appreciation. Foreigners owned huge amounts of dollar assets, but so did U.S. oligarchs. We fostered a global superclass aligned with this U.S. strategy. Bill Gates, the Saudi petrodollar, monarchy and Masayoshi Son of Softbank became a global system.

Gradually, this appreciation of financial assets got baked into every part of our society, what Joe Weisenthal calls the “number go up” dynamic. Every university endowment, every union pension plan, every 401k, and every foreign entity which holds U.S. assets is now dependent on financial valuations. All business school training and a hundred thousands of private equity executives are trained on this model, as are most corporate leaders. There’s a reason Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson went to China during the 2008 financial crisis and begged the Chinese government not to sell its Fannie and Freddie bonds. Maintaining ever higher financial assets is American strategy.

Weisenthal observed what happened when the U.S. government offered subsidies to chipmaker Texas Instruments. And he points that ‘number go up’ is a system.

Just last year, the activist investor group Elliott Investment Management took a $2.5 billion stake in Texas Instruments, calling for it to reverse plans to bring more manufacturing back in-house. Elliott's letter said that by rebuilding its manufacturing capacity, the company had "deviated from its longstanding commitment to drive growth of free cash flow per share."

Some might see this as the work of one greedy hedge fund. But a stock market that continues to go up is part of the entire US economic model. Rising stocks are how we pay for retirement, education, consumption, and so forth. To some extent, if you’re an investor in, say, a diversified index fund, you’re benefitting from the Elliotts of this world. They’re like the cops on the beat, keeping companies in check, focused on the mission of making the line go up. So any impulse to abundantly build out less profitable lines of business undoubtedly strikes at the heart of how American capitalism works.

And that’s why we keep seeing endless monopolization no matter how destructive. It’s why the U.S. didn’t take Covid seriously until the stock market dropped, because the stock market dictates our social policy. It’s why it’s so hard to block pharmacy benefit managers, despite them being obvious predators, and why the crypto scammers seem to have some sort of moral legitimacy. American policymakers, economists and thinkers, on the right and left, have a hard time imagining a different model other than “number go up.”

The Two Responses

With that context, explaining Trump’s tariff plan is relatively simple. Trump’s view is that the U.S. has been screwed by foreigners, which is only half true. He wants to shift some of the external trade arrangements so that the U.S. isn’t just producing dollars anymore but is making real things. Since he proposed significant tariffs on cars, and wants to do more this coming week, that’s going to hurt corporate profits. And number won’t go up. That’s quite significant.

Yet, Trump doesn’t believe in the necessary part of altering our national strategy, which is to move power from Wall Street to people who make things. It’s not just foreigners who screwed America, it’s also high finance. Trump is not displacing the domestic constituency groups who are dedicated to oligarchy, he’s knee deep in crypto, private equity, finance, and real estate. He’s destroying instead of reforming the institutions of a productive society, like universities and schools, public health bureaucracies, unions, and so forth.

But at least Trump is operating in a world where finance and production are real things. On the other side, Thompson and Klein, who both built their careers lauding the Obama administration, are proposing a path for the Democrats in the book Abundance, where they argue that liberals need to rededicate themselves to building by reforming zoning laws. It’s a short book, mostly reprints of their columns. And it’s basically the platform for what would have been the Kamala Harris Presidency.

It’s not very compelling; as Dave Dayen pointed out, in 2006, California built 200,000 homes, after the financial crisis it virtually stopped building homes. (UPDATE: I got the number wrong, it was something Dayen mentioned to me and I misheard.) That wasn’t a zoning problem. Overall, there’s not much substance to the book, it’s a reprint of neoliberal arguments from Democrats in the early 1980s. But the argument is less important than the power analysis. As Yale law professor and Abundance fan David Schleicher puts it, this particular book is part of a set of arguments from thinkers and economists, like Matt Yglesias, Noah Smith, Marc Dunkelman, et al, who think that power in America is “largely in the hands of growth-and-change skeptical professionals,” aka homeowners, environmentalists and doctors. Oligarchy and Wall Street, things like patents, monopolies, and the like, are irrelevant to these guys. If Trump doesn’t want to displace Wall Street, Klein and Thompson just ignore it altogether.

Both Trump’s tariff bonanza, and the attempted revival of neoliberalism, are falling a bit flat. Increasingly, Trump’s polling numbers suggest Americans distrust his work on the economy. The Republicans just lost a state Senate election in Pennsylvania where the district went 15 points for Trump. Another overwhelmingly Republican House seat in Florida is in a surprisingly tight race for a special election on Tuesday. And Trump pulled the nomination of Rep. Elise Stefanik for UN Ambassador for fear that heavily Republican seat would go to the Democrats.

On the other side, Klein and Thompson have been well-received on the podcasting circuit, but their book has been largely panned in reviews for lacking coherence. The most sophisticated and important review is that of Weisenthal, who wanted to like it, but did not. Klein and Thompson, and the Democratic establishment writ large, just will not deal with the real reason the U.S. doesn’t build. And that’s our choice to prioritize “number go up” and the social hierarchy of financiers we have fostered who thwart producing more. Fewer homes means that housing values appreciate, and in a world where asset appreciation is everything, that’s not a solvable political problem. Ultimately, Americans don’t want a world where asset valuations are everything. But that’s the world we’re in. And until someone figures out an off-ramp, the rage will appreciate in parallel with financial assets.

And now the news of the week. Read on for news about positive developments in debates within the Democratic Party, Clippy getting sad as the AI Ponzi bubble deflates, a collapse in mergers, data showing a slide into recession, and a Republican Senator takes a strong stance to keep you locked into Planet Fitness. Plus some more embarrassment for Democratic corporate lawyers…