For the last year or so, the global economy has been hammered by a massive supply chain crunch. The phenomenon is impossibly complex, encompassing a dizzying array of factors — demand shifts, the shift to e-commerce, Chinese industrial crackdowns, Covid, inflation, legacy regulations, trade imbalances, and much much more. But a small moment of clarity appeared in October, when Ryan Petersen, the founder and CEO of the supply chain software company Flexport, took a trip around the port of Long Beach and tweeted about a specific outdated regulation that was holding up the flow of goods. The city swiftly changed the regulation, and the congestion situation improved.

That episode suggests that the supply chain crunch isn't just one big thing — it's a ton of little things that we've allowed to build up over the years. So to get a bird's-eye view of the situation, I sent a list of questions to Ryan Petersen himself! In the incredibly informative interview that follows, Petersen explains how the U.S. and global supply chain system fell apart, and what policy changes and technological upgrades we can use to put it back together. If you want to understand the supply chain problem, start here.

Share

N.S.: The supply chain crunch has been the biggest economic story in the world for about a year now, causing inflation and throwing the Biden administration's plans into disarray. What sparked the supply chain crunch? How much of a factor was increased demand for physical goods due to the pandemic? Were shifting trade patterns at all to blame? Basically, why now?

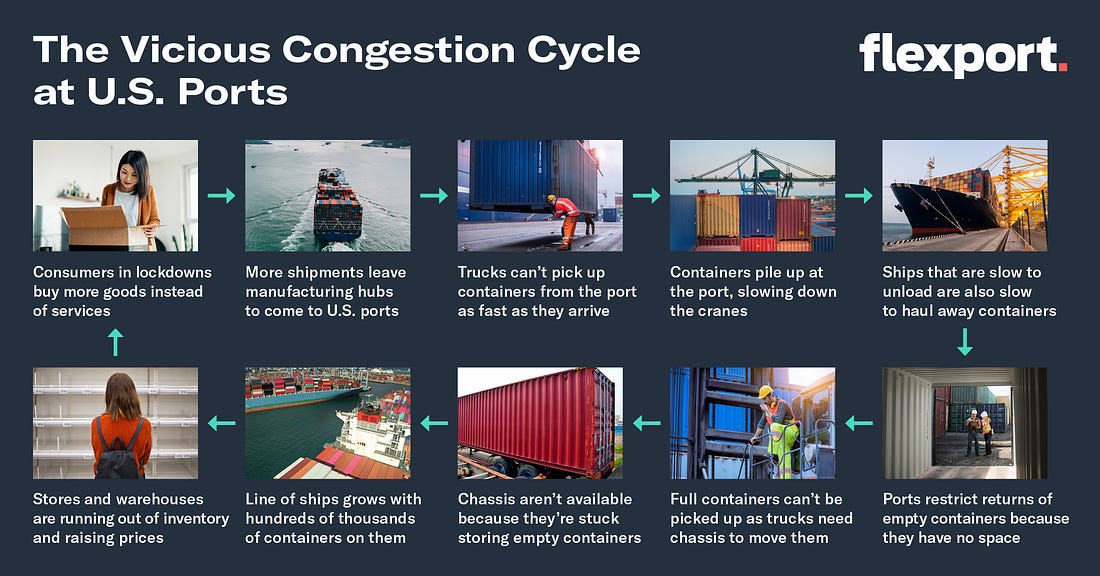

R.P.: The supply chain crunch was started by increasing demand for goods, as consumers stopped spending on services. Americans in particular had more money in their pockets because they weren't going on trips, spending at restaurants and bars, or attending concerts. Instead as city after city started enforcing lockdowns and restrictions, people started spending a lot more goods and not services. You've got to get your dopamine somewhere. So what we saw was an unprecedented increase in imports from China—as much as 20% more containers entering the United States than were leaving our ports since the start of the pandemic. It turns out, our infrastructure is just not made to scale this fast, and by infrastructure what we mean is the entire ecosystem: The number of container ships in the world, the number of containers available, the throughput of our ports, the availability of trucks and truck drivers, the availability of chassis (the trailers that haul containers around), the entire system is overwhelmed and clogged. We simply don't have enough of these essential supply chain elements, or resilient systems that are agile enough to shift the supply of these assets to where they're needed.

While the pandemic drove this shift in demand from services to goods, it also changed where consumers were buying goods (increasingly online), the types of goods they were buying, and where those goods were flowing to and from. One thing to note is that e-commerce logistics networks are fundamentally different in their geographical and physical space than that of traditional retail. They're more complicated because you are edge caching your inventory to be closest to your users instead of positioning everything in a distribution center in a single hub. You now have to position your warehouses all over the United States, making it exponentially more complicated. So the more people bought things online, the more these systems were overloaded.

Then there was the impact of cascading second orders that are inherently unpredictable. For example, as imports increased as much as 20%, exports actually decreased because the United States economy was slow to reopen. In fact exports are still down. If you look at the journey of a shipping container, it runs in a loop: The same container that brings in imports later helps transport exports out of the U.S. So if there are fewer exports going out, that means companies are consciously choosing to ship empty containers back to Asia or else they will run into shortages at the origin ports. At one point over the last year, as an industry, we were 500,000 shipping containers short in Asia. These shortages led to increases in prices. If you wanted to get a container you had to pay a real premium to get access. In some cases renting a container for one journey was more expensive than the price to buy one. In January 2019, rates on the Trans Pacific Eastbound route (TPEB), and Far East Westbound (FEWB) were around $3000. In December 2021, rates remained elevated in the $12,000 - $15,000 range. At one point this year, TPEB rates were as high as $24,000.

Consumers are just buying more stuff than ever and our infrastructure, frankly, isn't ready for it. It's getting held back by dilapidated port infrastructure, by congestion, non-automated ports, and bad rail connections to the ports. We're just recognizing the pain of 20 years of not investing in our infrastructure. And we're feeling all that pain in one year right now. It's increasingly difficult for truckers to pick up or drop off containers at ports and warehouses, leading to today's congested ports, lots, and railyards. So boats can't get in, we don't have enough containers, a lot of the empty containers are stuck on the chassis, we don't have enough chassis because we don't have enough warehouse space, and we don't have any space in the warehouses because we can't move the goods out fast enough.

Until we can focus on what actually clears the ports, rail yards and warehouses, and goods can begin to move at a pace that aligns more closely with the growth in consumer demand, there's nowhere for the containers to go, and the number of ships waiting to unload will continue to grow.

N.S.: How much of the crunch is international, vs. U.S.-specific?

R.P.: While the current supply chain crisis has global impact, the greatest delays by far are in the U.S., owing to port bottlenecks and trucking shortages. But, while it's true that in percentage terms the shipment time to North America had a more significant increase, this is not a purely U.S.-specific problem.

We have two recent Flexport Research reports that speak to this. First, we have a report that looks at the tilt toward consuming goods over services internationally. The U.S. had the second-biggest shift towards goods, behind the UK, but we did see a similar shift in 23 out of the 25 countries for which the OECD had the relevant data, showing this is a global trend.

Second, Flexport's Ocean Timeliness Indicator shows significant increases in journey time for both shipments from Asia to North America and shipments from Asia to Europe. For example, in mid-December, TPEB (Asia to North America) timeliness increased to a record 109 days from an already-high 106 days a week earlier. There was a significant increase in the time taken to ship from cargo origin to the Asian ports and sailing times also rose. And for FEWB it was 109 days.

The situation in Asian countries with manufacturing hubs has a role to play as well. Multiple factories in China, Vietnam and all over Asia have experienced closures and slowdowns due to Covid outbreaks among employees, and it's the same situation with some of their ports.

The U.S. and U.K. have seen the biggest shifts but also had the lowest proportion of goods versus services in pre-pandemic levels. That may explain why the logistics networks in both countries appear to have struggled versus their peers, though other factors such as Brexit clearly played a part, and the relationship is statistically weak.

To summarize, the wide range of economies facing elevated goods' share of household spending, and the continued divergence versus historic norms, shows that the demand shock for logistics networks is a global and persistent phenomenon.

N.S.: You had what's by now a sort of legendary adventure where you actually went to inspect the port of Long Beach, and you found that local regulations were preventing containers from being stacked high enough, causing backups that were ultimately keeping ships from being able to unload cargo. After you tweeted about it, the city revised its regulations. Did you sort of know that you would find something like that when you decided to tour the port? Is this a special case, or are there lots of little pointless regulations like this at ports all over the country?

R.P.: That was not actually my first port visit this year. I had gone down there a few weeks prior with a couple of Flexport colleagues because we wanted to see what was happening at the port firsthand. There's nothing better to do on a Saturday than a fun boat ride, so we went out on the water. What we saw was effectively that the port was not operating at full capacity, but we didn't know why and that kicked us off on a journey to try to better understand the cause of the congestion.

We started brainstorming ideas for how we could learn more about the situation on the ground. Who could we talk to that could help us understand things better? Port workers and track drivers seemed like the right place to start. The first thing we actually did after this boat ride was send a taco truck to the port and offer free tacos for the union workers there. While we had that time with them, we were able to ask questions and that's when I actually published my first tweetstorm on the LA/LB ports, which did got a lot of impressions but didn't have as high of an impact as my following tweetstorm about suggested fixes (which includes allowing truck yards to store empty containers up to six high instead of the current limit of 2).

Some port workers told us that one contributing factor was that truck drivers were not showing up for their appointments to pick up containers from the port. To pick up a container you need an appointment for a specific container number, and the workers at the port have to find that specific container amongst all those stacks and bring it to the front so it's there when the trucker shows up. We were told that truckers were missing 50% of all the appointments, and it was creating absolute chaos. So we talked to the CEO of a trucking company that we work with closely down in the Long Beach area who handles our port pickups, and we took him with us on that second boat ride in late October mostly to pick his brain because we didn't really believe that truckers were to blame. What was their side of the story?

This is one of the more important aspects of supply chain—the emphasis on chain. There are so many different companies and people involved. When you actually look closer, it's a complex network and adaptive system that everybody in the chain is optimizing for their own interests. So it's really important to get the different perspectives and hear as many viewpoints as possible to get the full picture. Everybody's operating sort of like that allegory of the elephant in a dark room where everybody's touching one body part and describing it and no one's really seeing the whole picture. Our plan was to synthesize that full story to get a coherent view. The Twitter thread that went viral was a result of our conversation with that CEO who told us that he has a severe shortage of chassis because they're already holding empty containers which his truckers are unable to store in his yard (lack of space) or return them to the port (because the ports are so full) and you end up in this Catch-22 situation.

You can't return empties, so you can't free up the chassis required to move full containers out of the port. And because you're not pulling the containers out of the port, you're not able to return empties to the port. I did not know that this was the case before I went down there. We only discovered it during that three-hour boat ride.

With regards to your question about whether there are pointless regulations all over the country, I think the answer is obviously yes. It's like the saying about advertising, that 50% of all your ad dollars are wasted but you just don't know which 50%. There are lots of good regulations too, and it's a very hard problem to solve. No government in human history that I'm aware of has ever figured it out.

N.S.: To follow up on that, do you think there's something systemically wrong with the way we do regulation in American ports? Is there some reason we're not quick to adapt regs to changing circumstances? Is it a cultural thing, where stuff has just kinda-sorta worked OK for so long that we've lost the flexibility to change when we need to? Or are there problems with the way regulatory authority is allocated?

R.P.: At one point this October, there were over 500,000 shipping containers on ships waiting out at sea, with an estimated $30 - $50 billion worth of merchandise in them. Much of it did not get into warehouses and shops in time for the holiday shopping season. If businesses who have imported all this merchandise don't get it in time, much of it goes unsold during their busiest season. That means huge write offs and losses. Secondly, shipping prices have gone through the roof so we're seeing a lot of inflation already and it's worse than is being reported. Ocean freight costs alone add 5% to 10% to the cost of everything we buy, and remember, 90% of the stuff we buy is shipped on a container ship. The globalized supply chain and shipping containers have brought down the cost of shipping goods and manufacturing by close to 90% over the last 50 years. If we lose that, that is a huge source of economic prosperity that's going to go away, and it won't be good for the U.S. economy, brands or consumers.

One thing to remember here is that in America, the ports are owned by the local city that they're in. Therefore, they're not managed as a strategic national asset, which they clearly are. We're realizing the implications of this right now. For example, I live in San Francisco and our main port is the Port of Oakland, which is owned by the City of Oakland. The mayor of Oakland has a lot of local issues to focus on and probably won't prioritize multi-billion-dollar investments in their port as the city simply can't afford it. So there's just an inherent underinvestment in many U.S. ports and until recently it was really hard to get the federal government to make major investments in our ports.

We've under invested in our supply chain infrastructure for over 20 years. In hindsight, the signs were there for years. Almost no logistics companies can show you where your freight is in real-time on a map. Most data is exchanged in unstructured email messages with attachments. There are almost no logistics APIs to speak of. The pandemic has dramatically amplified two major trends in supply chains: the rise of e-commerce and the diversification of global supply and demand. The internet has put consumers in the driver's seat: they can get what they want, when they want it. And they want it right now. If you can't get it to them right now, your competitor will. But both these trends long pre-date the pandemic and will continue for the next few decades. And both require more agile, tech-enabled logistics and supply chain infrastructure, federal level investment in our outdated infrastructure, and more automation.

We're going to get sub-optimal outcomes if you don't invest in technology. If we don't have robotics, if we don't have systems that are better at managing appointments for managing pickups and returns of containers at ports, if we don't have better safety mechanisms (some of these are incredibly hazardous jobs and robots would be far safer), it's going to take many years, not months to fix this crisis. Technology and automation have helped modernize and increase the efficiency of ports in other countries like the port of Rotterdam in the Netherlands, but that's because it's managed as a strategic asset for the country. It has been a fully automated operation for over 20 years so the technology exists, but we still have a lack of investment to implement those changes in the United States. That's a fundamental problem. The reality is if you want to be competitive globally, you need to have world-class infrastructure that enables U.S. businesses to lower costs and find their ideal customer, manufacturer or supplier or anywhere in the world. That's how they can grow their business provided our logistics networks are not holding back economic growth and progress. We simply have to have modern technology and be able to implement it.

N.S.: What should the Biden administration have done to overwhelm supply chain bottlenecks early on in the crunch? What should the administration be doing now?

R.P.: I think many of us imagined that we live in a world where there's a wizard behind the box. That there's actually somebody in charge of all of this, and that that somebody must have made a mistake. And of course, it must be the president of the United States. But that's not actually the world that we live in. It's a market-based system. We're lucky to live in an economy that's built on the principles of free enterprise, and so while it's easy to cast blame and point fingers at the administration, we have to recognize that they're not really in charge of all of these things. They didn't create this situation and I'm not 100% convinced that they're the ones that are going to be best equipped to solve the problem.

That said, there's a very clear role for our government to intervene in markets when you have systemic failures. As much as we love the idea of a free enterprise system, the reality is that markets often fail. And when they do, we need our leadership to step in and help resolve problems. I think what we're observing at West Coast ports right now can best be described as a market failure. So there must be some role for government to step in here. I outlined a few ideas for how the government can resolve supply chain bottlenecks in my Oct. 22 Twitter thread.

The first thing that I would do if I were in charge would be to actually put a team in charge. Right now, there isn't a dedicated team within the federal government to coordinate all public and private sector activities to help resolve the supply chain crisis. It's spread across multiple regulatory agencies, jurisdictions and levels of government. I don't have an opinion on who should be in charge, but if you're trying to address a market failure, you want to have a single person or team in charge that can dictate terms to all the different market actors. You saw this in the 2008 financial crisis where they put the President of the New York Fed and Secretary of the Treasury Timothy Geithner in charge of working with the private sector.

With that person in charge, you could then start to implement meaningful fixes. The two big bottlenecks are a lack of chassis and a lack of yard space both at the container terminals and in the yards around neighboring cities. We know that the federal government and the state government of California owns a lot of land so we'd love to see them make it available for storing containers and creating off-terminal storage facilities where truckers can pick up containers easily without having to wait in long lines at the gate to the ports.

Some of the simplest things we can do are changing zoning laws. President Biden needs to call the mayor of Los Angeles and ask him to implement the same container stacking rule that Long Beach adopted. It's still unclear to me why Los Angeles has not done this.

There are more drastic measures to consider like identifying borrowing chassis from the United States military, including the National Guard, to move containers. Right now, we have a real shortage of chassis and without them, you can't clear the bottleneck. So if the government has chassis anywhere in its reserves anywhere we need them. If we don't have a strategic reserve of chassis, maybe that's something that we should invest in to make sure this ever happens again.

N.S.: Was the global economy simply over-engineered? Did we optimize supply chains for efficiency at the cost of resilience, like a machine with tolerance gaps that are too small? And if so, should we recalibrate going forward, to leave more slack in the system in case of future crises?

R.P.: In my opinion, what's caused all the supply chain bottlenecks is modern finance's obsession with Return on Equity (ROE). To show great ROE, almost every CEO stripped their company of all but the bare minimum of assets. "Just-in-time" everything with no excess capacity, no strategic reserves, no cash on the balance sheet and minimal investment in R&D. We stripped the shock absorbers out of the economy in pursuit of better short-term metrics. Large businesses are supposed to be more stable and resilient than small ones, and an economy built around giant corporations like America's should be more resilient to shocks. However, the obsession with ROE means that no company was prepared for the inevitable hundred-year storms. Now as we're facing a hundred-year storm of demand, our infrastructure simply can't keep up.

Most global logistics companies have no excess capacity, there are no reserves of chassis, no extra shipping containers, no extra yard space, no extra warehouse capacity. Brands have no extra inventory and manufacturers don't keep any extra components or raw materials on hand.

And let's not forget the human aspect of the workforce that makes this all happen. A lot of companies in the industry haven't invested in taking care of their people, especially during market downturns, so now they can't staff up quickly to meet surging demand.

When the floods inevitably hit, the survivors will be those who invest in excess capacity, in strategic reserves of key capital assets, in employee trust that let them attract and retain talent. Running lean systems may seem beneficial, until the whole system fails like it did this year. We've removed the shock absorbers from the economy and it's time we add them back.

N.S.: Why aren't American ports more automated, like in other countries? Is it just politicians trying to protect blue-collar jobs? And if so, why have some countries like the Netherlands that have strong dock worker unions been able to successfully automate their ports, while we sit around and do nothing?

R.P.: If you look at the largest port in the United States, which is the Port of Long Beach/Los Angeles port complex (there's a jurisdictional line between the two cities that runs down the middle of the port), that port can only handle ships as large as 16,000 TEUs. (A twenty-foot equivalent unit or TEU is a unit of cargo capacity based on the volume of a 20-foot-long intermodal container, a standard-sized metal box which can be easily transferred between different modes of transportation, such as ships, trains, and trucks.) And this is the largest port in the United States. A few U.S. ports can handle 12,000 TEUs and most of the East Coast ones are even smaller than that. Today's largest ships are as big as 24,000 TEUs. If you look at the Ever Given—the most famous ship in the world that got stuck in the Suez Canal—it's almost 21,000 TEUs. So it would not be able to come to a U.S. port if it was full of containers. But there are other international ports like in the Netherlands that are able to handle these larger ships and have successfully automated a lot of their port operations.

The Dutch government has pushed for infrastructure innovation for decades and has a great working relationship with unions and employers through a polder model, which is based on consensus. This effort was started in the eighties. They used the polder model to successfully implement solutions developed by Delft University of Technology.

There were two reasons they were able to accomplish this:

- The Port of Rotterdam, a government-owned commercial entity running the port, had this vision way before other countries did as logistics is a key source of GDP in the Netherlands.

- They had a proper, documented approach to getting buy-in from multiple stakeholders through a polder model. The polder model is a method of consensus decision-making, based on the acclaimed Dutch version of consensus-based economic and social policy making in the 1980s and 1990s. The model is characterized by the cooperation between employers' organizations, labor unions and the government with a central forum to discuss labor issues (with a long tradition of consensus). This model helped them defuse labor conflicts and avoid strikes. Similar models are used in Finland.

We should really explore why the U.S. can't do what many mature and rapidly-growing economies already have. Big structural changes are hard to make, but we should at least start somewhere. For example, new technology can be used to eliminate appointments at terminals and allow truck drivers to just show up and take the first available container with a mobile app telling them where to go. We've already built this technology and it's ready to go right now and we believe it could clear the backlog at the Long Beach/Los Angeles ports within 30 days. However, it requires changes to contracts of who's responsible for picking up which container and a lot of coordination between the private sector, trucking companies, importing businesses, warehouses, ports and ocean carriers. This type of coordination is inherently difficult for the private sector to coordinate, where each is looking out for their own best interests. But in the interest of our nation's economy, right now this is a great role for the federal government to play. I strongly believe that all the private-sector parties would get onboard if you had strong federal leadership coordinating it, calling in favors and asking people to do their part on behalf of their country.

N.S.: Are there emerging technologies that could help us make our supply chains more resilient and flexible without sacrificing efficiency?

R.P.: Look around the room you're in and ask, "Who made that?" Everything you see was built and shipped from all over the world. Yet even though we're more connected than ever, our ability to ship, store, and trade goods has remained fragmented. Did you know it can take up to 20 companies to move a single shipment, each with their own system, processes, and documentation? This complexity keeps companies from growing and great ideas from reaching their potential.

Recent technological innovations like the Flexport Platform are simplifying global trade by connecting everyone in the supply chain. What the internet has done for bits, logistics technology solutions are doing for physical goods: giving every business the ability to grow globally and reach any customer, wherever they are.

Technology platforms are the way forward, powering every part of the economy: how we buy and sell, pay and get paid, and run companies in the cloud. Next-generation logistics platforms like Flexport can connect the entire ecosystem of global trade, empowering buyers, sellers and logistics providers with solutions and technology to grow and innovate.

Some of the new and emerging solutions that can help supply chains become more flexible and resilient include:

● Real-time tracking, exception alerts, milestone updates, landed costs, and inventory impacts, transit time, and container utilization, all at your fingertips

● More visibility with a single-source-of-truth for your supply chain. Customizable views to give everyone in your supply chain the insight and tools they need.

● Immediate Exception Management—being able to flag any exceptions or changes in a shipment's lifecycle and quickly fix issues before they result in demurrage, late fees, or other snafus.

● A multi-modal booking system that brings it all together: FCL, LCL, air, trucking, and rail. A unified view to help you balance speed, cost and compliance.

● Real-time collaboration to manage orders from suppliers, track your containers in motion, know what's inside them, and how that impacts inventory. More accurate, SKU-level visibility, door-to-door.

● Tools to ingest, digitize and store all your commercial documents in one place so you can search by SKUs, HS codes, POs, styles, or custom tags—instantly. No more time lost bouncing between systems.

● Public APIs with easy integration to automate full data visibility from purchase order to invoicing, saving time, reducing errors, and improving decisions.

Flexport provides all this and much more to our customers today.

N.S.: On that note, what do you think are generally the most interesting and exciting emerging technologies in logistics and supply chains? If I were a young engineer or entrepreneur who was interested in going into logistics, what would I want to be looking at right now?

R.P.: There's a ton of innovation going on in the logistics and supply chain space right now and we're really excited to work with the industry to find solutions that make global trade easier and more accessible for everyone. Some of the emerging innovations we're excited about include:

● Self-driving trucks

● Drilling tunnels or even hyperloops to allow containers to skip the LA traffic and be transported inland at rapid speeds. It doesn't make sense that we bring all containers into Los Angeles, the city with the country's most notorious traffic jams. So after you wait all this time to pick up a container from a congested port, you don't have to get on the 405 freeway and sit in bumper-to-bumper traffic.

● Startup Incubators that are investing in emerging logistics technologies including ODX Flexport that we are partnered with.

● Sustainability solutions for the industry. Ocean shipping contributes 1 billion metric tons of carbon emissions each year. Flexport.org is a critical part of the Flexport mission. Since its founding, we've offset over 150,000 tons of CO2 emissions. We enable brands to measure their emissions with our free, accredited carbon calculator.

● The use of technology to find the optimal mix of ocean, rail, air and trucking to lower a brand's carbon impact. Flexport's platform and the Flexport.org team analyze our clients' emissions to find the right reductions for their business. We also partner with organizations like GoodShipping to help change the global fuel mix—enabling decarbonization through sustainable marine biofuels.

● The massive cargo ships of today aren't able to fit at many of the ports around the world leading to congestion at a handful of ports. We're excited to invest in startups like Fleetzero working to decarbonize the cargo shipping industry with zero emission battery-powered container ships that could help ease supply chain snarls. Electric power allows for smaller and less complex ships which are less susceptible to route disruptions, mechanical breakdowns, and port constraints.

N.S.: What's next for Flexport? Will your company be able to capitalize on efforts to upgrade and improve our supply chains?

R.P.: We want to make global logistics as reliable as the electrical grid. When you flip a light switch, you just get power. You take it for granted. But what's actually happening is an incredibly complex coordination where a power plant somewhere in the world is getting slightly hotter just to provide you that extra dose of electricity that you need. It's the same thing people expect when they buy something in a store or online, that there's an incredibly sophisticated logistics network orchestrating things in the background to make sure that product arrives at your door. That's not actually how it works today. There are armies of people pushing paper, duct taping the system together, making phone calls and sending emails, and it's almost a miracle that any of it works. Flexport wants to make global logistics so reliable that businesses can count on our technology and solutions every time, with minimal effort. So brands of every size can really focus on what they need to do: make amazing products, connect with customers, and grow their business. That's the core need of any business. We also want to create an infrastructure layer that includes financing, insurance, compliance, customs and other services that you don't have to worry about. These operations are only going to get more and more complex in the years to come.

The rise of e-commerce means brands need a much more sophisticated and complex network with far more inventory, which means more risk and capital outlays. You need to be able to load balance: know where to position inventory to be ready for future growth, but not have so much inventory that it goes unsold and the business fails. This is a problem that companies are struggling to solve today. Businesses need good data to understand where bottlenecks are and good partners to support them. The traditional freight forwarding businesses do not provide automated load balancing and network optimization solutions to businesses. Your customers want exactly what they want, when they want it, and if you can't deliver, your competitor will. Flexport wants to build a technology platform that enables companies to thrive in this environment, giving them the infrastructure to meet customer demands and grow their business, without having to hire a huge bureaucratic back office to make decisions. We're now in a realm where machine learning is needed to solve these complex problems, not spreadsheets.

One of the biggest opportunities that we see in global logistics is that there isn't great data on all of the world's logistics assets, trends, and the supply and demand for those assets. Our in-house research team has created a number of helpful economic indicators that enable you to understand the latest trends, the throughput at various ports, and the transit time on every trade lane. We are building this ecosystem using service-oriented architecture in an API-first manner so that any company can tap into our data. In time we hope that this can become a developer platform, so that supply chain technology companies don't need to build out the graph of all the

logistics networks, but can tap into our data to power all their applications. It's still early days but we're investing aggressively to make sure that we are the leaders in this space, and then we're creating this as an open platform so that any company, including potentially competitive businesses, can tap into it.

We're shaping the future of a $8.6T industry by reimagining how brands move goods—fast, with confidence, and at scale. And while we're doing all this, we're also investing in making logistics a positive force for social and environmental impact. Our non-profit arm Flexport.org has delivered aid to over 66 countries and offset over 150,000 tons of CO2 emissions. Through greenhouse gas mitigation, discounted shipping, and product-donation matchmaking, we help nonprofits, NGOs, and Flexport clients with their social and environmental impact.

Easier and faster access to data—and the transparency it enables—has the power to catalyze global trade. From the biggest retailers to the newest brands, and from the most established carriers to the hottest delivery startups, we're excited to power a new generation of solutions that make global trade easy for everyone.

NEW DELHI – The World Inequality Report 2022, produced by the Paris-based World Inequality Lab, is a remarkable document for many reasons – starting with its demonstration of the immense power of patient collective research.

3Add to Bookmarks

PreviousNext

The report provides the latest estimates, based on careful aggregation of national data from a multitude of sources, of income and wealth inequality at the national, regional, and global level. It gives long-run time-series data for these indicators, allowing us to consider recent patterns in a broader historical context. And it expands on different dimensions of inequality in revealing new ways.

Any research enterprise as ambitious as this one will inevitably elicit quibbles about the datasets used, the assumptions required to generate particular series, and the ways in which some data gaps have been filled. My own minor criticism relates to the World Inequality Lab's use of purchasing power parity (PPP) exchange rates to determine and compare national incomes across countries.

As I have argued elsewhere, while PPP exchange rates appear to control for cross-country differences in price levels and living standards, they are ridden with conceptual, methodological, and empirical problems. For starters, PPP exchange rates assume that the structure of each country's economy is similar to that of the benchmark country (the United States) and changes in the same way over time. When applied to developing economies, this assumption is especially weak.

Moreover, the convoluted weighting procedure for goods can result in the inclusion of unrepresentative, high-priced products that are rarely consumed in some countries. For example, Angus Deaton has noted how packaged cornflakes may be available in poor countries but are bought by only a relatively small minority of rich people. Expenditure weights from national accounts do not reflect the consumption patterns of people who are poor by global standards.

There is a further, and possibly even more troubling, conceptual issue. High-PPP countries – that is, those where the actual purchasing power of the local currency is deemed to be much higher than its nominal value – are typically low-income economies with low average wages. PPP is high precisely because a significant section of the workforce receives very low remuneration, which means that goods and services are available more cheaply than in countries where the majority of workers receive higher wages. The widespread incidence of unpaid labor in many poor households in low-income countries further amplifies the effect. So, it is clear that the local currency's greater purchasing power reflects conditions of indigence and low or no remuneration for what could even be the majority of workers.

PPP-modified GDP data may therefore miss the point. By regarding greater purchasing power of a given monetary income as an advantage, rather than a reflection of the greater absolute poverty of the majority of an economy's workers, PPP estimates effectively overstate poorer countries' incomes compared to those of rich economies.

For all these reasons, relying on PPP exchange rates in cross-country income comparisons – including for poverty and inequality measures – is extremely problematic. There is a strong case for sticking to market exchange rates in measuring cross-country inequality, which would likely reveal much greater disparities than those evident in the World Inequality Report.1

This objection notwithstanding, the report adds much to our understanding of inequality, especially through two new measures. The first is the female share of labor income, which is a useful indicator of gender inequality. Globally, this share has remained largely unchanged over the past three decades, at one-third, and has been as low as 10-15% in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) and below 20% in Asia excluding China. This indicator captures not just labor-market imbalances, but also, implicitly, the greater proportion of unpaid work performed by women within households and communities, which reduces their access to paid work and affects their remuneration in paid employment.

The second innovative measure examines inequality in carbon-dioxide emissions by assessing contributions by income category across countries. The important finding here is that, while inequalities in emissions across regions are high and persistent, such disparities exist not only between rich and poor countries, but within them. There are high emitters among the rich in low- and middle-income countries, and relatively low emitters among the poor in high-income countries.

For example, the richest 10% of people in the MENA region emit 33.6 tons of CO2 per person per year, compared to less than ten tons among the bottom half of the income distribution in North America. (The bottom 50% in Sub-Saharan Africa emit one-twentieth of the North American amount, or 0.5 tons per capita per year.)1

Globally, the richest 10% of the population is responsible for more than half of all CO2 emissions. This point is especially important because, as the report notes, environmental policies like carbon taxes hit the poor the hardest, but this group is rarely if ever compensated for such measures. The new indicator enables a much richer consideration of what socially just climate policies should look like, both within and across countries.

Predictably, the report is strong on appropriate redistributive policies, especially the potential for increased taxation of wealth and corporate profits. There is also scope for looking more closely at "predistribution," or the range of regulatory regimes and legal codes that have enabled today's excessive concentration of wealth and income in the first place.

The primary cause of "predistributive" inequality is, in a word, privatization: of finance, the natural commons, the knowledge commons (through intellectual-property rights), and public services and amenities. One could add to that states' tendency – glaringly obvious since the 2008 global financial crisis – to protect large-scale private capital, while allowing it to wreak havoc on ordinary citizens.

The reality captured by the World Inequality Report reflects human choices, which means that it can be changed by making other choices. That is why the report is much more than a valuable compendium of useful data and analysis. It is a guide to action.