https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2021/10/25/stocks-profit-margins-and-the-economy/

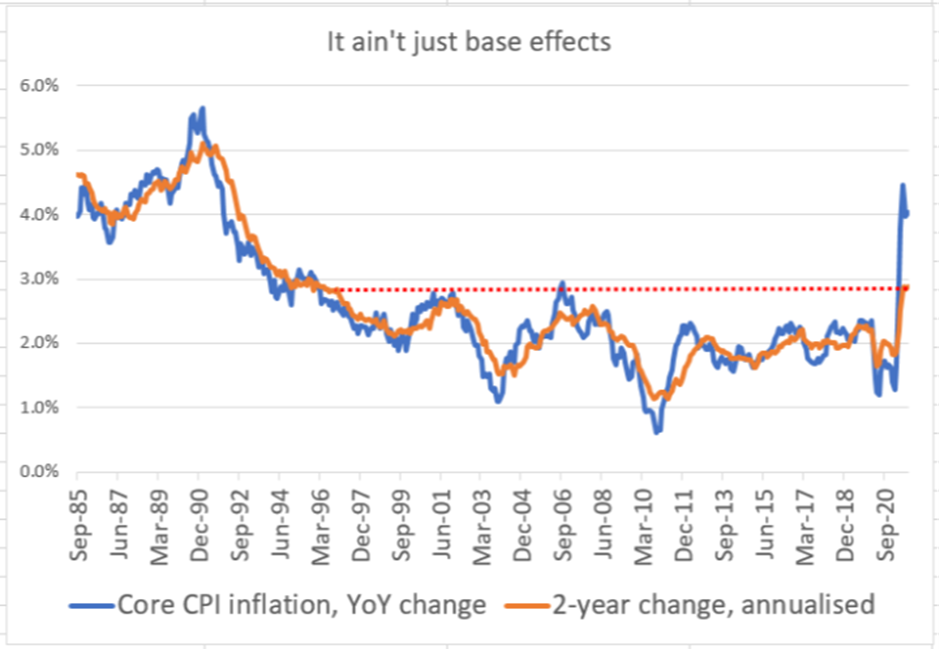

The US stock market went back to record highs last week. This was despite media talk that the recent rise in goods and services prices inflation in the major economies may continue for some time ahead. This led to further hints that not only would central bank injections of credit money (quantitative easing) be tapered back soon; but also central banks would soon start to hike their policy interest rates. The Bank of England chief economist, Huw Pill, a follower of the hard-line 'orthodox' German economist Otto Issing, emphasised that the central banks' task was not to boost the economy but to control inflation. Financial markets took that to mean that the BoE would be hiking rates very soon – even at the next November meeting of the policy committee. As a result, bond yields (the rate of interest on government bonds purchased in the bond market) rose to levels not seen for some time.

A rise in the cost of borrowing should lead to a fall in stock market investment as most financial investors borrow to speculate. However, the US stock market seems impervious to the news on inflation and interest rates. Why is that?

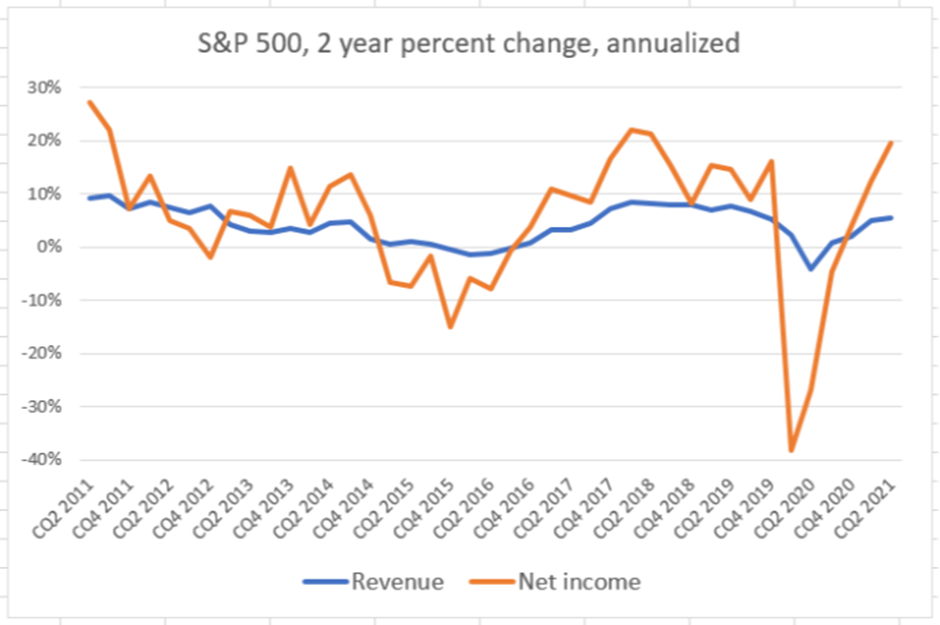

The reason seems to be that investors are still convinced that the global economy is recovering fast as the vaccines roll out and the fiscal stimulus plans of many governments, particularly the US, are to continue. As a result, forecasts of revenues and earnings being made by companies are very strong, with earnings rising at a 20% yoy pace.

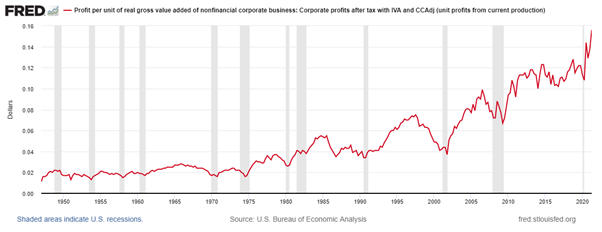

Indeed, if we look at profit margins ie profits per unit of output, then margins appear very high indeed, at around 14%, up sharply from the pre-pandemic. Corporations in the US and Europe have been registering huge profits this year that comfortably compensate for any reductions during the pandemic slump.

How does that square with the data which show that the profitability of capital in the US is near record lows?

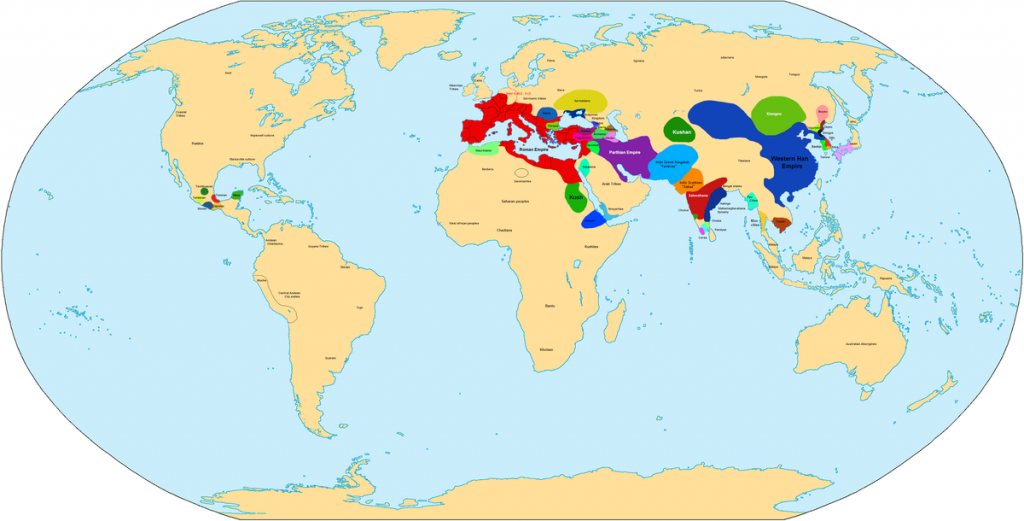

Well first, both the stock market jump and the profits being recorded are heavily concentrated in the information technology sector and within that, the so-called FAANGS. This was something I and others pointed out before the pandemic struck in 2019. But it is even more so in 2021. The IT sector contributes 25% of all US non-financial corporate sector profits. And the other large contributor to profits is the consumer media sector, where Amazon dominates (50% of profits in the sector). So if you strip out these sectors from the stock market and the profits data, then the rest of the corporate sector is not doing so well, at all. Moreover, US corporate profits have been heavily subsidised in the last year from government handouts.

This explains the numerator in the measure of average profitability of capital in the US. Then there is the denominator. Profit margins measure profits against output. But profitability of capital measures profits against the cost of fixed assets (plant, machinery, technology) and the wage bill. And investment in fixed assets has been weak, in the sense of delivering productivity-increasing technology outside the tech sector itself. Vast swathes of industry and services in the US, Europe and Japan are barely making enough profits to cover the depreciation of existing assets and the cost of debt incurred. Investment (capex) relative to depreciation, which measures investment in new technology, has been declining over the long term, and especially in the pandemic slump, with little sign of recovery in 2021.

So while the tech sector holds up the stock markets and gives the impression of a widespread leap forward in profits, the rest of the capitalist economy is in the doldrums and has been throughout the 'long depression' of the 2010s. While the 'old economy' only represents about 35% of global gross domestic product, it generated at least twice the amount of corporate losses; and had about 90% of non-financial debt.

What is noticeable when we get to the so-called 'real economy' and away from the fantasy world of the stock and bond markets (the markets for what Marx called 'fictitious capital') is that the recovery from the pandemic slump of 2020 is beginning to falter.

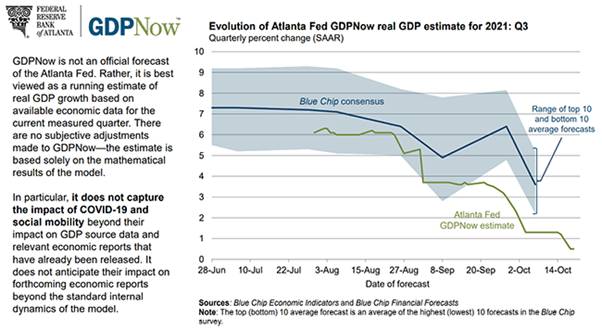

The Atlanta Fed GDP Now forecast model tracks the data coming out of the US economy and then makes a forecast for real GDP growth. As of 19 October, the model forecast that the US economy grew by only 0.5% (on annualised basis) in the third quarter of 2021 that ended in September.

Now this is well below the consensus forecasts which are more like a 3-4% pace. But even the consensus reckons the US economic recovery slowed sharply in the third quarter. We shall get official preliminary estimates this week. JP Morgan economists have noted the slowdown in Chinese growth, caused by continued COVID issues, weak growth in Asia, lack of raw materials and the impending residential property crisis. And they now forecast just 3% growth in the US in Q3. But they expect continued robust expansion in Europe, so that global growth was likely around 3.4% in Q3.

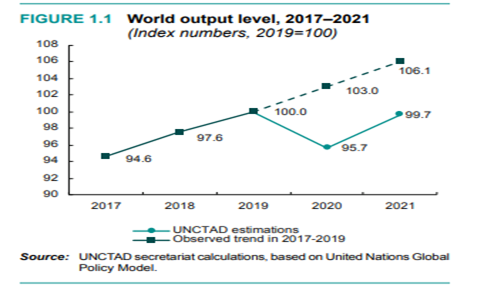

However, JPM reports that "this outcome would represent a substantial step back in the speed of the recovery. Relative to our forecast at the start of last quarter, the 3Q21 global GDP shortfall from its pre-pandemic pace has deepened by over a percentage point and now points to a 2.7% journey back to a complete recovery". Indeed, by the end of 2022, JPM still expects world GDP to be below the pre-pandemic level – and well below where world GDP would have been without a pandemic slump. The recovery is not V-shaped but a reverse square root – see my 2021 forecast back in January.

The fantasy world of rising stock market prices can continue further, but the market is based on foundations of shifting sand. Sure, profit margins in the tech sectors in the major economies are still strong but outside of that sector, margins are tight. With inflation rising, central banks are increasingly having to consider 'normalising' monetary policy and hiking rates. If that happens, then the costs of debt servicing will rise. And if the shortage of labour in key sectors continues, then wages could also move up. Profit margins will then contract and the great stock market pandemic rally will reverse in 2022.

-- via my feedly newsfeed