Over the past several months, conservative lawmakers and activists have carried out a concerted assault against a wide range of efforts and ideas that raise awareness about the history of racial injustice in the United States, its embeddedness in our society, and the resulting inequities observed today. Attackers have grouped and conflated all these concepts and ideas into what they are dubbing "critical race theory." But those carrying out this campaign are not interested in what the actual academic critical race theory (CRT) says. In fact, what is actually under attack is the reinvigorated movement across the United States to engage in dialogue about our country's continuing legacy of racial hierarchy and oppression—and the policy choices that could finally begin to redress that legacy. And while the campaign against critical race theory is recent, it is merely the latest tool many states have wielded in order to disempower and further disenfranchise Black people as well as cut off any broad-based support for structural reform.

Before the latest right-wing scapegoating tactic, critical race theory was seldom discussed among the general public. It is an academic discourse mostly taught in law schools that calls for an examination of our legal system from a racial lens, arguing that the law is not neutral and has been a tool to maintain racial hierarchy. Conservative attackers fomenting controversy rarely engage with the substance of critical race theory; instead, they attack any public discussion, organizing movement, policy effort, or—most concerningly—public education that acknowledges that the founding of our nation is rooted in the enslavement of people of African descent for their labor, and the genocide and plunder of Indigenous peoples for their land. They also attack any call for changes in our economic, legal, and cultural domains to address some of these harms that have compounded for centuries.

Historical context

These attacks are the latest examples of white backlash to perceived progress, upward mobility, and equality for Black people. Throughout U.S. history, reactionary politics have always followed periods of potential redemptive transformation. The short—yet significant—period of Reconstruction after the U.S. Civil War serves as a pivotal example of this. In what the historian Eric Foner calls "this first experiment in genuine interracial democracy in the South," the Reconstruction era saw transformative voting rights legislation passed as well as the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, which guaranteed equal citizenship to anyone born in the United States

However, by the end of the 19th century, white backlash ended Reconstruction. The Jim Crow era of racial segregation—legitimized by the 1896 Supreme Court Plessy v. Ferguson decision—reigned supreme. Poll taxes and literacy tests replaced the Reconstruction universal male suffrage laws and the Ku Klux Klan spread in influence and membership. White backlash and violence were prevalent both in periods of economic growth, especially Black economic growth as seen by the Tulsa Massacre of 1921 and others, and in periods of economic downturn, such as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. This historical context matters because, as the current anti-CRT vitriol shows, these trends continue today. The historical backlash, violence, and racist legislation not only destroyed lives, livelihoods, and wealth at the time, but crucially, cut off wealth-building and intergenerational wealth. White backlash and violence have persistent economic effects and impact current inequality and material wellbeing. Recent scholarship from Jhacova Williams, for example, has shown that areas with high rates of lynchings have lower Black voter registration today.

Legislative fights in the states to censor public education

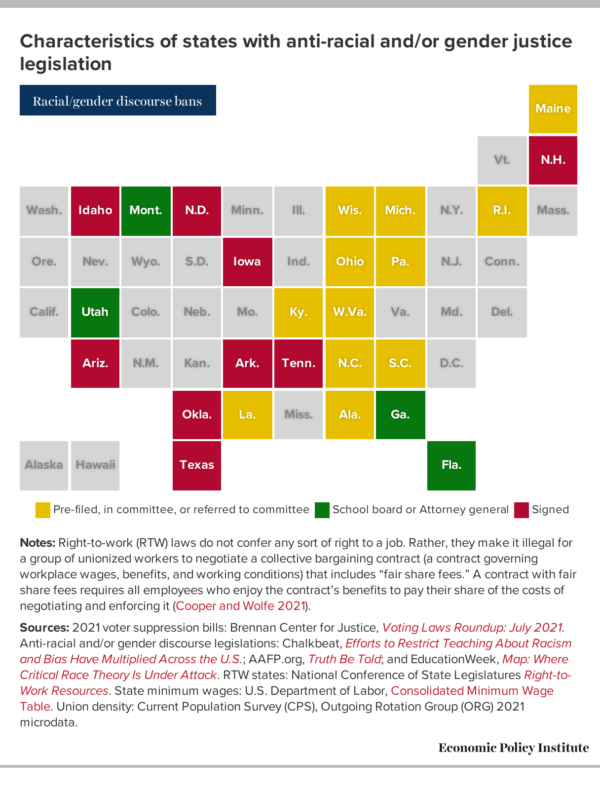

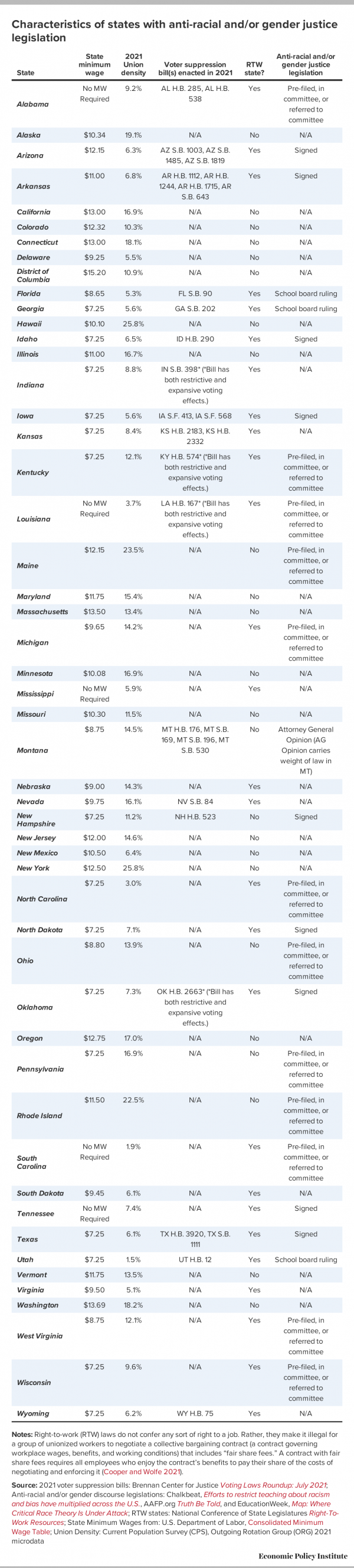

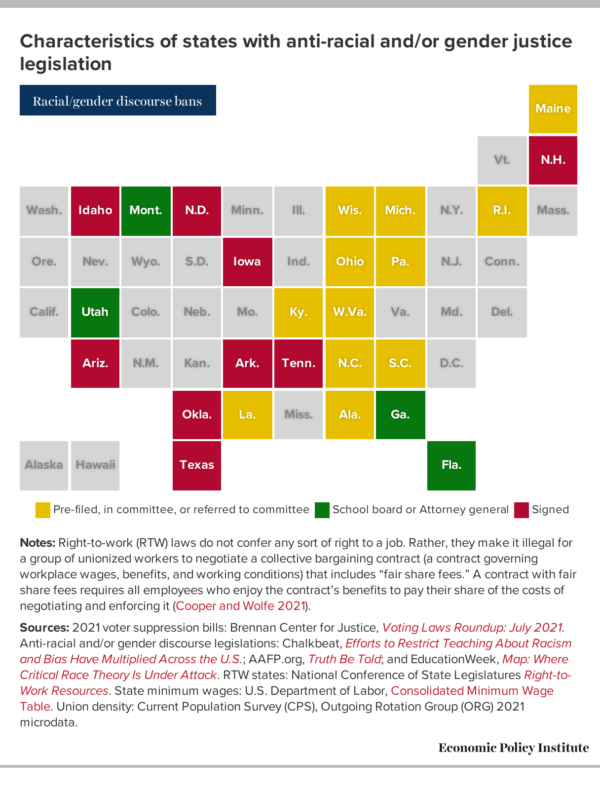

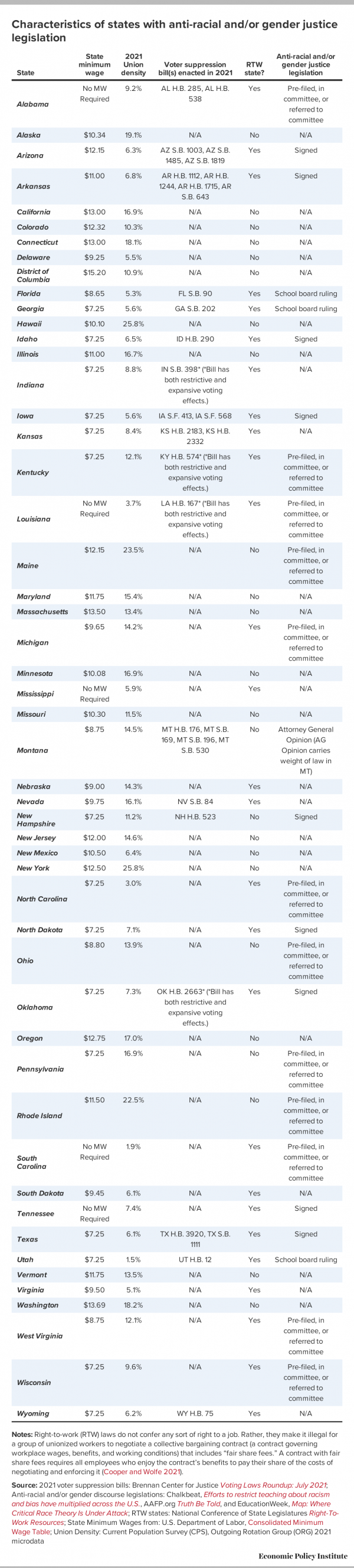

The attacks against "critical race theory" are not a random occurrence by a few fringe agitators—they are pervasive and insidious state-sponsored attempts to disempower and disenfranchise marginalized and racialized communities. These right-wing attacks have escalated from a mere dog whistle into serious and concerning legislative action and censorship. Several states have passed legislation banning or hindering teachings on the country's history of racial and gender-based hierarchy and its contemporary ramifications, mostly in K-12 schools. These states include Arizona, Arkansas, Idaho, Iowa, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Texas. In Florida, Georgia, and Utah, school boards have restricted teachings on race-related topics.

Policymakers in dozens of other states have introduced legislation or campaigns to restrict education on racial injustices and related biases in what are thinly veiled attempts to censor and promote a revisionist whitewashed history. Some, such as Alabama's pre-filed bill, ban the teaching of any concepts about critical race theory and make broad statements such as "The Alabama State Board of Education believes that the United States of America is not an inherently racist country, and the state of Alabama is not an inherently racist state." Arizona's signed bill prohibits the teaching of unconscious bias or responsibility for historic acts of racism. Tennessee's signed bill withholds funding from schools if teachers connect events to institutional racism.

The fight for civil rights has always been intertwined with worker power and economic justice. Thus, it is not surprising, and in fact deliberate, that the same states enacting bills under the banner of stopping critical race theory are the same states that have historically disempowered workers and today exhibit the worst racial economic inequities. As shown in Figure A and Table 1 of the appendix, the states where lawmakers have advanced these harmful bills also have low rates of unionization, more voter suppression bills, and are more likely to be so-called "right-to-work" states. These states have long disempowered workers and underinvested in community and worker wellbeing.

Map

These right-wing efforts are a distraction from pivotal opportunities for change

Beyond the direct harm to the country's children and schools, this coordinated campaign to fuel racism is also intended to divert attention away from the critical policy reforms that this moment demands. Media attention has shifted away from the promises and demands for civil rights and economic transformation that buoyed the Biden administration into power. Instead, it has fixated on superficial commentaries on this culture war.

The American Rescue Plan (ARP) Act should serve as the beginning of long-needed policy reform to transform our economy and livelihoods. What state legislators and advocates need to prioritize right now is equitable spending of ARP funds that centers racial, gender, worker, and immigrant justice to ensure a recovery for all that goes beyond merely restoring our pre-pandemic economy. The complement to this spending is establishing progressive revenue streams that simultaneously fix the regressive nature of most state tax codes while securing long-term funding for critical public services, and equity-promoting, people-centered budgets and programs. This includes ending the reliance in many localities on fees and fines as a major source of government funding.

State usage of ARP funds to address issues like the Black maternal health crisis, for example, would get us closer to achieving the goals of the civil rights movement. In a period plagued by a global pandemic that has shed light on so many of our societal woes and compounding inequalities, significant and deliberate investments to address the racialized and gendered social determinants of health and related outcomes should be our focus. Rather than returning to a pre-pandemic normal, we should be making long-term investments in education as well as other wealth-building mechanisms, such as improving access to credit and banking, distributing baby bonds, or cancelling student debt. We must recognize the latest right-wing frenzy for what it is—an attempt to distract from the reforms needed to make us a more inclusive and equitable society.

A race-conscious view of our policies and the ways they maintain but can also dismantle systems of oppression is what we need right now. Legislation like the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act, for example, would address some of the unequal bargaining power between employees and employers by making it easier for workers to unionize. Among other reforms, the PRO Act would outlaw so-called "right-to-work" laws that weaken unions and bar workers from the better pay and working conditions won through collective bargaining. Unions can be particularly powerful in boosting pay for workers of color. Unionization is also correlated with lower levels of inequality and greater educational investment as a whole. As we show above, the states most effectively and successfully passing anti-critical race theory bills are the same states with very low or no minimum wages and low rates of unionization. They are also more likely to have already passed voter restriction bills in 2021 alone.

Conclusion

The brutal and publicized murders of Black and Latinx people at the hands of the police and armed civilians have motivated widespread organizing and energy around the need for systemic reforms. These efforts have been directed towards the centuries' long fight against the pervasive anti-Blackness in our legal, economic, and cultural systems and narratives. Many of the economic disparities we see and fight against today have roots in the segregation and economic oppression following Reconstruction.

We must not let another white backlash continue to entrench poverty, immobility, and economic disparities. Fortunately, the threat to democracy and authoritarian streak of this backlash is finally getting greater media coverage. Still, it is up to all of us to see through the transformations necessary to meet the demands of the recent racial justice and health crises and their collision with centuries' old inequality and injustice in our nation. Our political (re)imaginations must center life-altering material gains, where civil and economic transformations toward equity intersect. The fight for a 21st century New Deal centered on racial, gender, and worker justice must remain lawmakers' focus.

Table 1

-- via my feedly newsfeed