https://equitablegrowth.org/the-relationship-between-taxation-and-u-s-economic-growth/

Overview

The relationship between taxation and economic growth is hotly debated in economics. Free market economic ideology is based on the premise that constraining "the market" through policies such as increased taxes is bad for economic growth.1 Yet the economy is not perfectly represented by abstract theoretical models. Empirical studies based on real-world data are often unable to find these negative growth effects. Because neoclassical economic models consistently fail to accurately predict economic growth patterns, policymakers need to rethink using them to analyze tax changes.

Researchers have studied many different fluctuations in U.S. tax policy over the past several decades. In 1997, for example, the United States had much higher average tax rates and especially much higher rates of taxation on wealth and capital than it does today.2 Recent years have seen the passage of a major tax cut in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act and new proposals from the Biden administration to raise revenue from the richest Americans.3

This issue brief examines if, in recent U.S. economic history, there is empirical evidence linking economic growth and:

- The broad tax regime

- Top individual income tax rates

- Corporate tax rates

- Capital taxation

- U.S. income and wealth inequality

In light of the evidence surveyed, the brief closes by discussing the proper way for policymakers to judge and evaluate tax proposals. Because classical models lack strong explanatory power in practice, U.S. policymakers should not focus on economic growth as an outcome in tax policy formulation. Rather, they should focus on the actual, meaningful, and measurable effects of tax changes, such as their impact on government revenues and the distribution of income.

Tax evasion and economic inequality

Even classical economic models are unlikely to assume that proposals to raise revenue by combatting tax evasion would hurt U.S. economic growth. Tax evasion introduces inequities and inefficiencies into the tax system. To the extent that policymakers can cut down on evasion, this can reduce inequality and raise valuable revenue to invest in American families. Read more here: https://equitablegrowth.org/the-sources-and-size-of-tax-evasion-in-the-united-states/

The broad relationship between tax rates and U.S. economic growth

Supply side and neoclassical models rose to prominence in the 1970s and 1980s, promising faster economic growth. Unlike the Keynesian model used in the mid-20th century, which had very little to say about taxes, supply-side economics and other neoclassical models champion a "free market"-centered view that frames taxes as the enemy of economic growth.4

In the 1980s, policymakers followed these models and drastically lowered the top individual marginal income tax rate, from about 70 percent down to 28 percent, and lowered the top corporate rate from 46 percent down to 34 percent.5 But instead of booming, income growth slowed. As the government reduced statutory tax rates, especially for those at the top, inequality exploded, and income growth rates went down. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Drawing definitive conclusions from these types of correlations is not possible because there is no counterfactual. But it is clear that the U.S. economy grew more slowly after top rates were drastically lowered than it had grown previously.

The Congressional Research Service also finds that broad empirical data are the opposite of what neoclassical models predict. The U.S. national savings rate, for example, declined in the 1980s after taxes on capital dropped, and it again declined after capital tax cuts in the 1990s and 2000s; neoclassical models predict the opposite would happen.

Additionally, U.S. labor supply, measured by the number of hours worked, has broadly declined as top personal income tax rates have declined; neoclassical models would likewise predict the opposite. Again, there is no counterfactual, but even subcomponents of growth—in these cases, savings rates and labor supply—have behaved the opposite way free market, or supply-side, economists would predict.6

In addition, Chye-Ching Huang of New York University and Nathaniel Frentz of the Congressional Budget Office produce a review of dozens of peer-reviewed studies on the relationship between taxation and economic growth in 2014 and find that the academy was highly conflicted. "Taking all of these studies into account, there is simply no consensus that, as a general proposition, cutting taxes is a good strategy to boost economic growth," they report.7 More recent evidence has not changed this conclusion, as detailed below.

Top individual income tax rate and U.S. economic growth

The current top marginal income tax rate is 37 percent, or up to 40.8 percent for some taxpayers when combined with two Medicare surtaxes. The Biden administration offered proposals to raise the top rate back to 39.6 percent, where it was for most of the 1990s and 2010s.8 Analysts who rely on neoclassical models argue that there are large trade-offs between having a strongly progressive tax system and economic growth.9 But this theoretical trade-off is not apparent in the economic literature.10

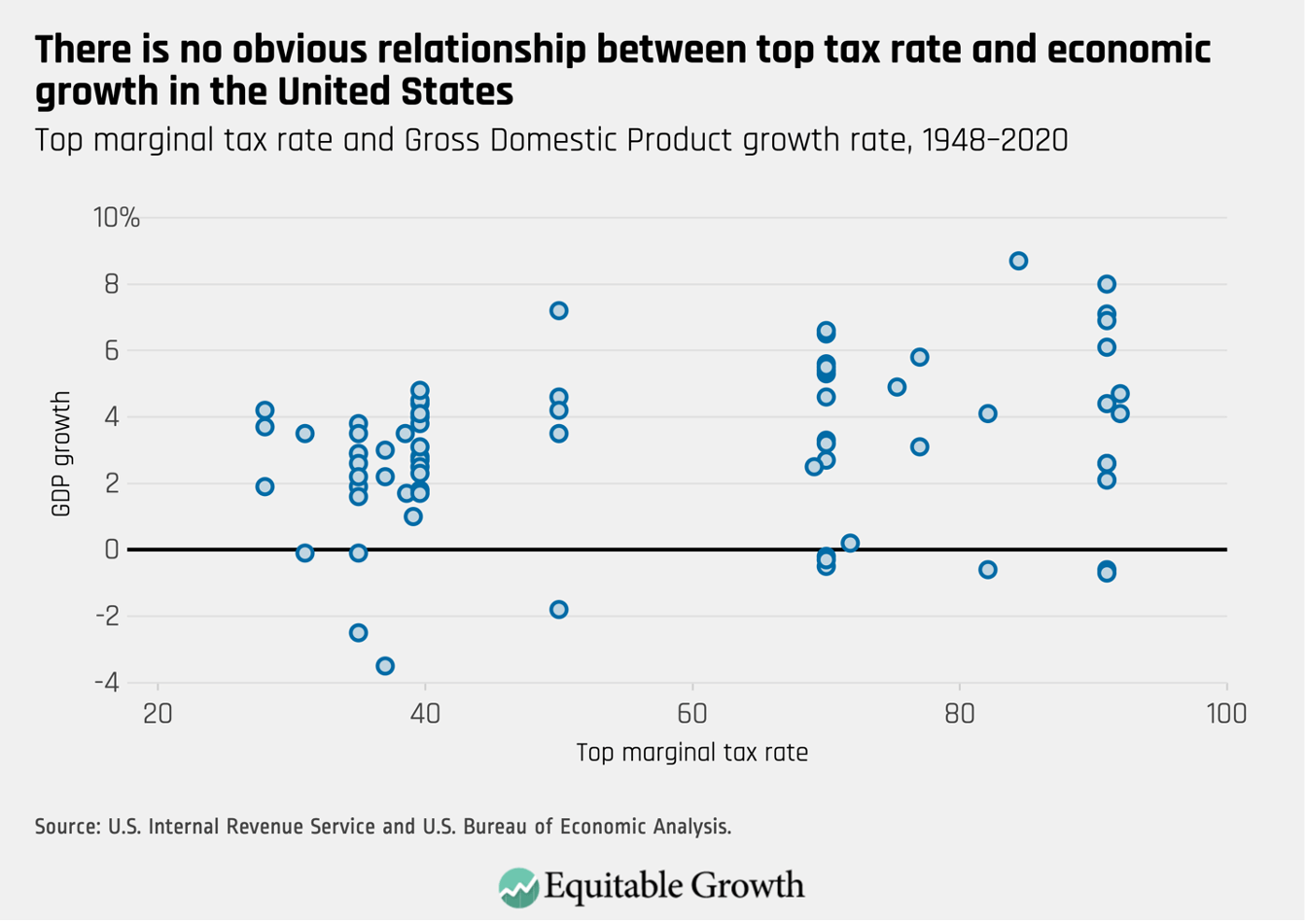

A tax and economic growth trade-off also is not present in the data. Over time, there has been no obvious relationship between U.S. economic growth and the top marginal rate applied to individuals' regular income. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

In fact, over time, high top rates are correlated with higher economic growth for most Americans, according to research from University of California, Berkeley economist Emanuel Saez. His research on the effects of the Obama administration's 2013 tax increases on individual taxpayers making more than $250,000 per year concludes that they were efficient at raising revenue and "the top tax rate increases of 1993 and 2013 do not seem to have hurt overall economic growth, quite the contrary."11

Saez finds that "the best growth years for the bottom 99% incomes since 1990 have taken place in the mid to late 1990s and since 2013, shortly after increases in top tax rates." On individual rates, the empirical pattern has been the opposite of what neoclassical models predict, casting doubt on these models' ability to say anything meaningful about growth following tax increases on the rich.

Corporate rate cuts have not boosted U.S. economic growth

The biggest recent test case for the theory that tax rates have strong effects on economic growth was the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Among other changes, this law lowered the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent. At the time, the Trump administration's Council of Economic Advisers claimed that "reductions in effective corporate tax rates have substantial, positive short- and long-run effects on output," primarily by increasing "firms' investment, desired capital stock, and potential output," which would lead to "wage increases for U.S. households of $4,000 or more" and "much of this boost to U.S. output may be apparent in the near term."12

As many analysts confirm, these predictions did not occur. Steve Rosenthal at the Tax Policy Center reports that even a full 2 years after passage, the United States was "without resulting investment or wage growth, or even green shoots."13

The 2017 tax cuts' lack of effect on wages in its first 2 years surprised few analysts, but the law's lack of effect on corporate investment was particularly striking. While investment can be volatile, the Congressional Research Service notes that the biggest bump in investment since its passage occurred in the first half of 2018, too early to be the plausible result of a tax change just months before because investment decisions take time to plan and execute.14

Moreover, the Congressional Research Service finds that investment increases (such as they were) were in subcategories that didn't correspond to the provisions of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. For instance, intellectual property investment grew fastest in 2018, even though the law paradoxically raised the user cost of investing in intellectual property, with factors other than tax cuts driving those changes.15

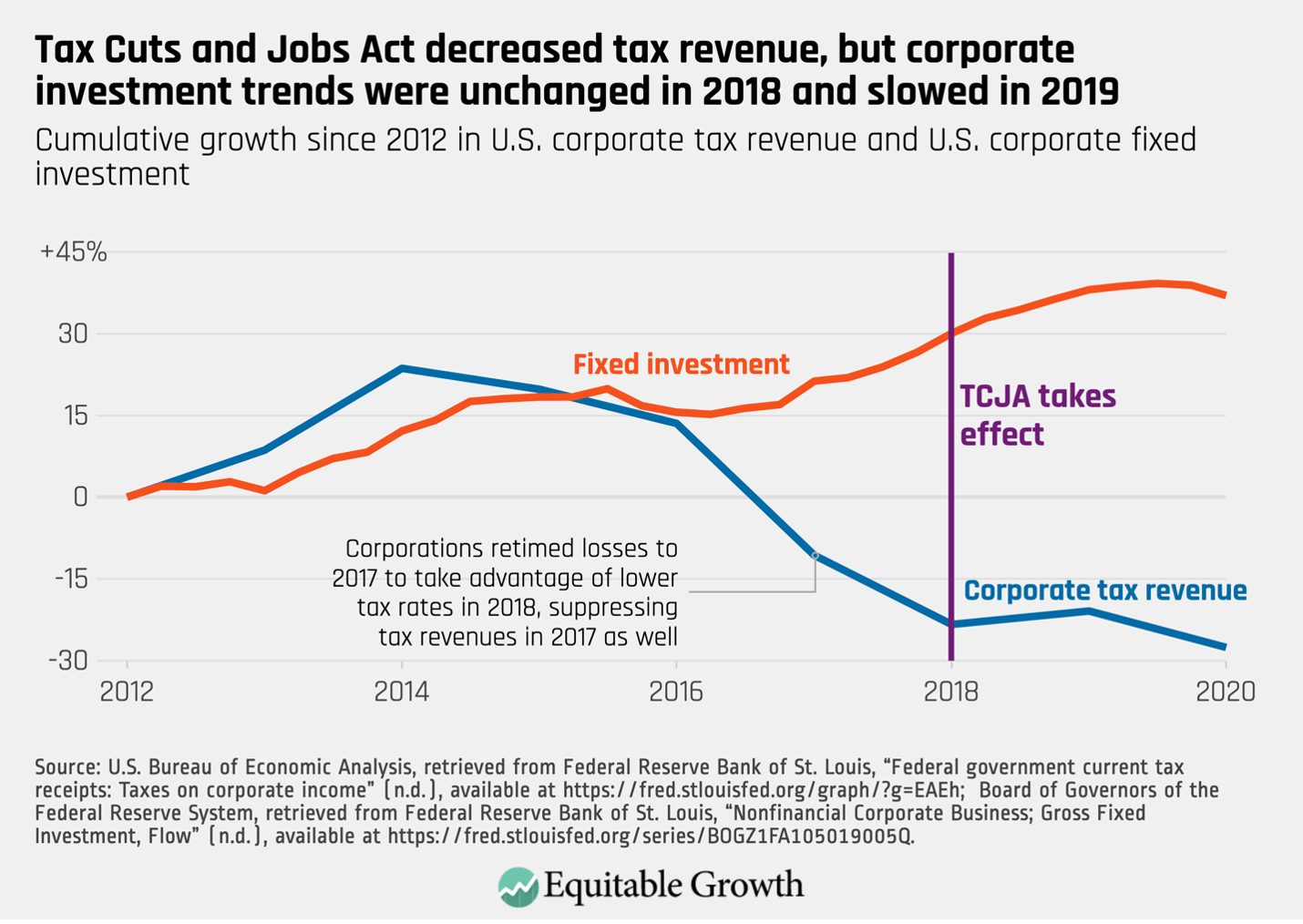

Indeed, there was strong growth in fixed investment in the year before the 2017 tax cuts passed, which carried over into 2018 before stagnating in 2019. This is despite the long and sustained fall in tax revenue, which began dropping in 2017 as corporations used accounting techniques to ensure losses would start appearing the year before the new rates hit to take full advantage of the cut. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

So, what did corporations spend their large tax cut on, if not wages or investment? Analysts at the International Monetary Fund find that 80 percent of the corporate tax cuts were repurposed into stock buybacks and dividends, which overwhelmingly benefited wealthy shareholders.16 And Lenore Palladino of the University of Massachusetts Amherst documents that these corporate buybacks and dividends also widened the racial wealth divide, finding that White stock-owners hold $27 for every $1 in corporate equity and mutual fund value held by a Black or Hispanic stock-owner.17

The main effects of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act were less government revenue and regressive tax cuts for corporations, wealthy shareholders, and executives who bear nearly all the burden of corporate taxes even as the rate changes had little effect on business investment or workers.18

Capital taxation and U.S. economic growth

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the United States significantly reduced the taxation of capital. For instance, the top capital gains rate was lowered from 28 percent in 1997 to 15 percent in 2003, before being raised back to 20 percent, plus a 3.8 percent Medicare surcharge, in the early 2010s. Meanwhile, taxes on dividends were reduced from nearly 40 percent down to the capital gains rate of 15 percent in 2003.

There are often confounding factors that make it difficult for data to precisely show what effect a tax change has on the economy, but occasionally, natural experiments do arise. The 2003 dividend rate cut provides an ideal test case to measure the effect of a capital tax cut on growth. Equitable Growth grantee and UC Berkeley economist Danny Yagan (now at the White House Office of Management and Budget) compares the behavior of C-corporations, which experienced the dividend tax rate drop from nearly 40 percent to 15 percent, to other, similar businesses (S-corporations) that were not affected by the tax cut to demonstrate why only shareholders gained from those dividend cuts.19 (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

Similar to the pattern after the 2017 tax cuts passed, Yagan finds that the main effect of the dividend tax cut was that C-corporations increased payments to their shareholders. C-corporations did not increase employee compensation or investment after they received their tax cut, when compared to unaffected S-corporations. Contrary to claims from the law's proponents and neoclassical economic models, cutting dividend taxes more than in half did not boost economic growth but did reduce government revenue and increase inequality.

U.S. income and wealth inequality and growth

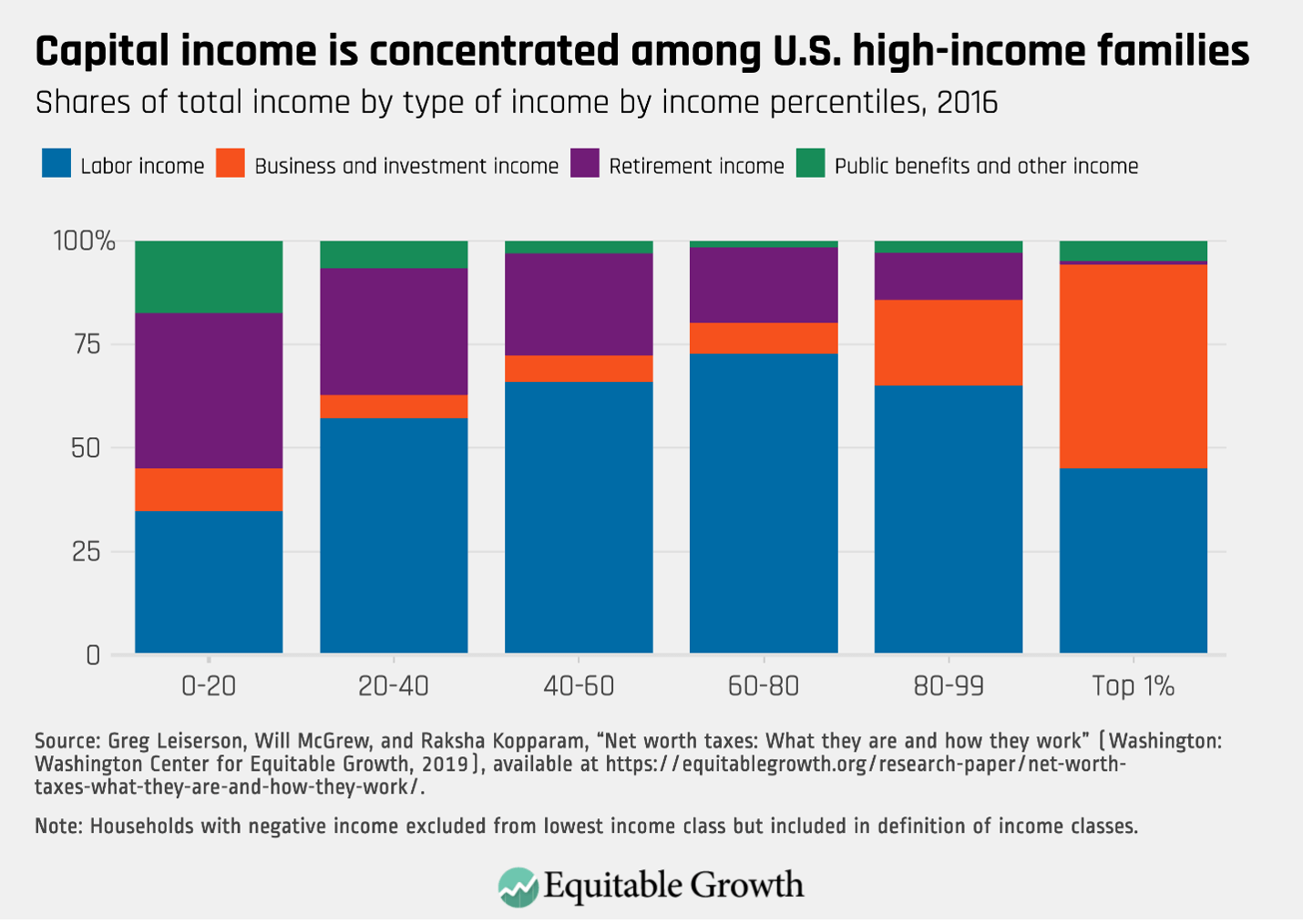

Cutting taxes for the owners of businesses and other forms of capital rarely had perceptible effects on investment or economic growth, but these cuts still have economic effects. Because capital income is so unequally distributed, lowering business and investment tax rates creates an upward income redistribution, enriching the already-wealthy. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

While there is no discernable positive correlation between upper-income tax cuts and U.S. economic growth, there is a clear correlation between these tax cuts and income inequality. When the United States began lowering top marginal income rates and taxes on capital income, such as investments, corporations, and other businesses, the income of the richest 1 percent of U.S. families grew. The 1980s were a period with many economic and policy changes besides tax cuts for the wealthy, so tax cuts cannot be said to be completely responsible for this trend, though they contributed. (See Figure 6.)

Figure 6

Low taxes on accumulated wealth also help the already-wealthy and powerful maintain and grow their privilege over other Americans. Wealth inequality is growing.20 Refusing to tax these gains helps the beneficiaries of past policy choices maintain their economic and social power, even when past wealth was gained in a context of racist and sexist economic structures.21 (See Figure 7.)

Figure 7

In general, neoclassical economic models have neglected economic inequality as a driver of slowing growth, decreasing dynamism, and stagnating well-being over the past several decades, argues Heather Boushey in her most recent book Unbound: How Inequality Constricts Our Economy and What We can Do About It. Boushey finds that lowering taxes at the top helped to fuel the rise of inequality, which has obstructed, subverted, and distorted the pathways to broadly shared growth.

Post-1980, economic policymaking focused more on allowing the already-wealthy to keep more and more gains, meaning this wealth has not "trickled down" or been reinvested in ways that build growth for middle- and lower-income Americans. This also starved the public sector of resources to build structures that lift up those who have been systemically disadvantaged historically. The result is that public investment has fallen, and the top 1 percent benefits disproportionately from the slower economic growth the United States is still experiencing.22

The economy is complex, and there are many factors that determine growth and well-being that short-run neoclassical models fail to capture. For instance, the returns from many investments in children and families are so high that they outweigh the plausible economic benefits claimed by tax cut boosters, says the former Vice Chair of the Federal Reserve Board Alan Blinder.23 This is the crucial part of analyzing a tax that many models undervalue: the benefits from the spending that taxes enable.

To the extent policymakers judge economic policy on its "growth" effects, they should consider who benefits from the growth that occurs.24

How policymakers should judge tax changes

So, how should policymakers judge proposed taxes if the data on tax changes rarely reflect classical analyses' predictions? The answer, as former Equitable Growth Tax Policy Director Greg Leiserson writes, is "if U.S. tax reform delivers equitable growth, a distribution table will show it."25 A revenue analysis explains how much money will be collected or lost, and a distribution analysis explains who will pay for or benefit from the tax. Numerous complex calculations and assumptions underlie the production of revenue and distribution tables, but when done well, they provide the key information that policymakers need to know about how tax changes will impact the populations they care about.

Analyses of taxes' effects on economic growth, while often sparking interesting academic debates, do not tell policymakers anything they cannot learn by looking at a revenue analysis and a distribution table produced by rigorous, nonpartisan groups such as the U.S. Congress' Joint Committee on Taxation and the Tax Policy Center.26

Conclusion

This issue brief shows that while tax changes can have large effects on the U.S. economy, they have not noticeably affected overall economic growth or corporate investment in recent decades. Instead, the research and data firmly establish that the main effects of tax changes are to increase or decrease inequality and government revenue.

The post The relationship between taxation and U.S. economic growth appeared first on Equitable Growth.

-- via my feedly newsfeed