https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2021/05/30/the-productivity-crisis/

It has been the historic mission of the capitalist mode of production to develop the "productive forces" (namely the technology and labour necessary to increase the output of things and services that human society needs or wants). Indeed, it is the main claim of supporters of capitalism that it is the best (even only) system of social organisation able to develop scientific knowledge, technology and human 'capital', all through 'the market'.

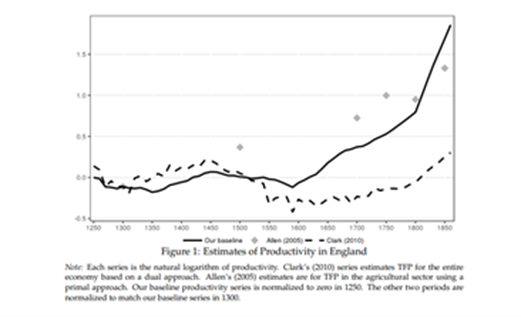

The development of the productive forces in human history is best measured by the level and pace of change in the productivity of labour. And there is no doubt, as Marx and Engels first argued in the Communist Manifesto, that capitalism has been the most successful system so far in raising the productivity of labour to produce more goods and services for humanity (indeed, see my recent post). In the graph below, we can see the accelerated rise in the productivity of labour from the 1800s onwards.

But Marx also argued that the underlying contradiction of the capitalist mode of production is between profit and productivity. Rising productivity of labour should lead to improved living standards for humanity including reducing the hours, weeks and years of toil in producing goods and services for all. But under capitalism, even with rising labour productivity, global poverty remains, inequalities of income and wealth are rising and the bulk of humanity has not been freed from daily toil.

Back in 1930, John Maynard Keynes was an esteemed proponent of the benefits of capitalism. He argued that if the capitalist economy was 'managed' well (by the likes of wise men like himself), then capitalism could eventually deliver, through science and technology, a world of leisure for the majority and the end of toil. This is what he told an audience of his Cambridge University students in a lecture during the depth of the Great Depression of the 1930s. He said: yes, things look bad for capitalism now in this depression, but don't be seduced into opting for socialism or communism (as many students were thinking then), because by the time of your grandchildren, thanks to technology and the consequent rise in the productivity of labour, everybody will be working a 15-hour week and the economic problem will not be one of toil but leisure. (Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren, in his Essays in Persuasion)

Keynes concluded: "I draw the conclusion that, assuming no important wars and no important increase in population, the 'economic problem' may be solved, or be at least within sight of solution, within a hundred years. This means that the economic problem is not – if we look into the future – the permanent problem of the human race." From this quote alone, we can see the failure of Keynes prognosis: no wars? (speaking just ten years before a second world war). And he never refers to the colonial world in his forecast, just the advanced capitalist economies; and he never refers to the inequalities of income and wealth that have risen sharply since the 1930s. And as we approach the 100 years set by Keynes, there is little sign that the 'economic problem' has been solved.

Keynes continued: "for the first time since his creation man will be faced with his real, his permanent problem – how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares, how to occupy the leisure, which science and compound interest (!MR) will have won for him, to live wisely and agreeably and well." Keynes predicted superabundance and a three-hour day – the socialist dream, but under capitalism. Well, the average working week in the US in 1930 – if you had a job – was about 50 hours. It is still above 40 hours (including overtime) now for full-time permanent employment. Indeed, in 1980, the average hours worked in a year was about 1800 in the advanced economies. Currently, it is still about 1800 hours – so again, no change there.

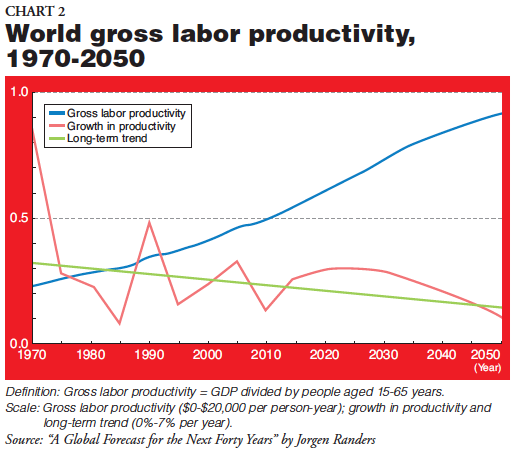

But even more disastrous for the capitalist mission and Keynes' forecasts is that in the last 50 years from about the 1970s to now, growth in the productivity of labour has been slowing in all the major capitalist economies. Capitalism is not fulfilling its only claim to fame – expanding the productive forces. Instead it is showing serious signs of exhaustion. Indeed, as inequality rises, productivity growth falls.

Economic growth depends on two factors: 1) the size of employed workforce and 2) the productivity of that workforce. On the first factor, the advanced capitalist economies are running out of more human labour power. But let's concentrate on the second facto in this post: the productivity of labour. Labour productivity growth globally has been slowing for 50 years and looks like continuing to do so.

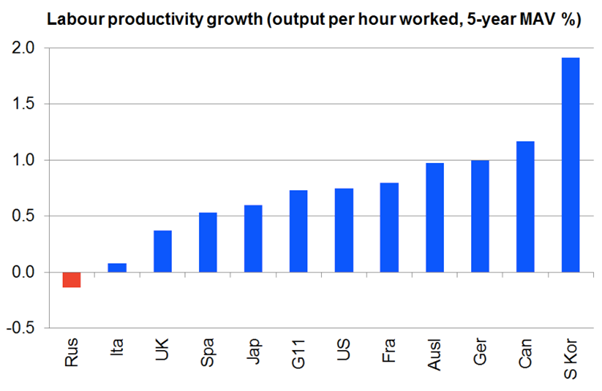

For the top eleven economies (this excludes China), productivity growth has dropped to a trend rate of just 0.7% p.a.

Why is productivity growth in the major economies falling? The 'productivity puzzle' (as the mainstream economists like to call it) has been debated about for some time now. The 'demand pull' Keynesian explanation that capitalism is in secular stagnation due to a lack of effective demand needed to encourage capitalists to invest in productivity-enhancing technology. Then there is the supply-side argument from others that there are not enough effective productivity-enhancing technologies to invest in anyway – the day of the computer, the internet etc, is nearly over and there is nothing new that will have the same impact.

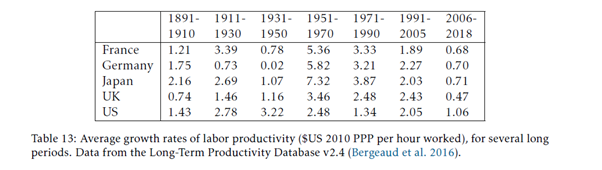

Look at the average growth rates of labour productivity in the most important capitalist economies since the 1890s. Note in every case, the rate of growth between 1890-1910 was higher than 2006-18. Broadly speaking, labour productivity growth peaked in the 1950s and fell back in succeeding decades to reach the lows we see in the last 20 years. The so-called Golden Age of 1950-60s marked the peak of the development of the 'productive forces' under global capital. Since then, it has been downhill at an accelerating pace. Annual average productivity growth in France is down 87% since the 1960s; Germany the same; in Japan it is down 90%; the UK down 80% and only the US is a little better, down only 60%.

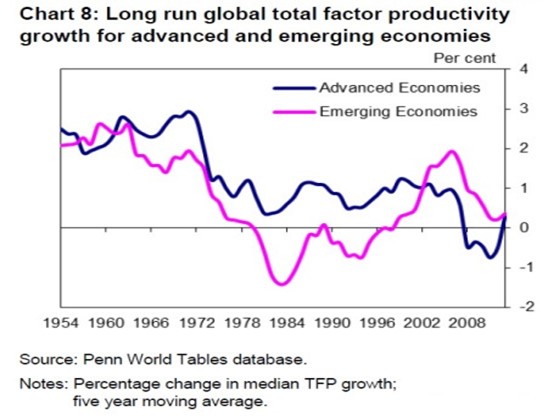

There are three factors behind productivity growth: the amount of labour employed; the amount invested in machinery and technology; and the X-factor of the quality and innovatory skill of the workforce. Mainstream growth accounting calls this last factor, total factor productivity (TFP), measured as the 'unaccounted for' contribution to productivity growth after capital invested and labour employed. This last factor is in secular decline.

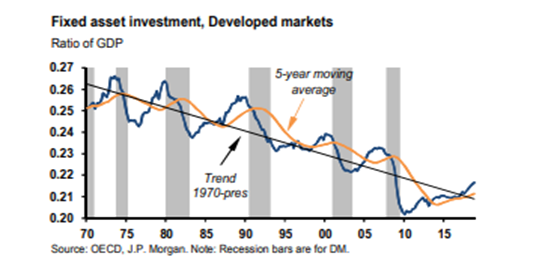

Corresponding to this slowing of labour productivity is the secular fall in the fixed asset investment to GDP in the advanced economies in the last 50 years ie starting from the 1970s.

Investment to GDP has declined in all the major economies since 2007 (with the exception of China). In 1980, both advanced capitalist economies and 'emerging' capitalist ones (ex-China) had investment rates around 25% of GDP. Now the rate averages around 22%, a more than 10% decline. The rate fell below 20% for advanced economies during the Great Recession.

The slowdown in both investment and productivity growth began in the 1970s. And this is no accident. The secular slowing of productivity growth is clearly linked to the secular slowing of more investment in productive value-creating assets. There is new evidence to show this. In a comprehensive study, four mainstream economists have decomposed the causal components of the fall in productivity growth.

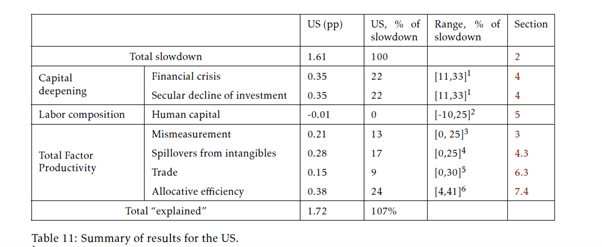

For the US, they find that, of a total slowdown of 1.6%pts in average annual productivity growth since the 1970s, 70bp or about 45% was due to slowing investment, either caused by recurring crises or by structural factors. Another 20bp of 13% was due to 'mismeasurement' (this is a recent argument trying to claim that there has been no fall in productivity growth). Another 17% was due to the rise of 'intangibles' (investment in 'goodwill') that does not show an increase in fixed assets (this begs the question of whether 'intangibles' like "goodwill'' are really value-creating). About 9% is due to the decline in global trade growth since the early 2000s; and finally near 25% is due to investment by capitalists into unproductive sectors like property and finance. The four economists sum up their conclusions: "Comparing the post-2005 period with the preceding decade for 5 advanced economies, we seek to explain a slowdown of 0.8 to 1.8pp. We trace most of this to lower contributions of TFP and capital deepening, with manufacturing accounting for the biggest sectoral share of the slowdown."

In other words, if we exclude 'intangibles', mismeasurement and unproductive investment, the cause of lower productivity growth is lower investment growth in productive assets. The paper also notes that there has been no reduction in scientific research and development, on the contrary. It is just that new technical advances are not being applied by capitalists into investment. Now maybe, the rise of robots and AI is going to give a productivity boost in the major economies in the post-COVID world. But don't count on it. As the great productivity theorist of the 1980s, Robert Solow, put it in a famous quip 'you can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics' (Solow 1987).

If investment is key to productivity growth, the next question follows: why did investment begin to drop off from the 1970s? Is it really a 'lack of effective demand' or a lack of productivity-generating technologies as the mainstream has argued? More likely it is the Marxist explanation. Since the 1960s businesses in the major economies have experienced a secular fall in the profitability of capital and so find it increasingly unprofitable to invest in heaps of new technology to replace labour.

And when you compare the changes in the productivity of labour and the profitability of capital in the US, you find a close correlation.

Source: Penn World Tables 10.0 (IRR series), TED Conference Board output per employee series

I also find a positive correlation of 0.74 between changes in investment and labour productivity in the US from 1968 to 2014 (based on Extended Penn World Tables). And the correlation between changes in the rate of profit and investment is also strongly positive at 0.47, while the correlation between changes in profitability and labour productivity is even higher at 0.67.

And as the new mainstream study also concludes, there is another key factor that has led to a decline in investment in productive labour: the switch by capitalists to speculating in 'fictitious capital' in the expectation that gains from buying and selling shares and bonds will deliver better returns than investment in technology to make things or deliver services. As profitability in productive investment fell, investment in financial assets became increasingly attractive and so there was a fall in what the new study calls "allocative efficiency" in investment. This has accelerated during the COVID slump.

There is a basic contradiction in capitalist production. Production is for profit, not social need. And increased investment in technology that replaces value-creating labour leads to a tendency for profitability to fall. And the falling profitability of capital accumulation eventually comes into conflict with developing the productive forces. The long-term decline in the profitability of capital globally has lowered growth in productive investment and thus labour productivity growth. Capitalism is finding it ever more difficult to expand the 'productive forces'. It is failing in its 'historic mission' that Keynes was so confident of 90 years ago.

-- via my feedly newsfeed