https://www.epi.org/blog/cbo-analysis-confirms-that-a-15-minimum-wage-raises-earnings-of-low-wage-workers-reduces-inequality-and-has-significant-and-direct-fiscal-effects-large-progressive-redistribution-of-income-caused/

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Worthy reads from Equitable Growth:

1. Ultimately—no, not ultimately, but rather immediately—whose property the law will protect is a political decision made in the interests of those whom the government listens to, in the triple senses of protecting it from theft or expropriation, protecting it from damage, and protecting it from devaluation. If you don't have a political voice, whatever property you do accumulate is likely to be evanescent and to be worth little. Read David Mitchell, Austin Clemens, and Shanteal Lake, "The consequences of political inequality and voter suppression for U.S. economic inequality and growth," in which they write: "Those who enjoy market power are, not coincidentally, often the same citizens who enjoy outsized political influence, creating a feedback loop that perpetuates economic inequality, instability, and slow growth. This report examines cutting-edge research on how economic and racial inequality interact around the country among those Americans who vote, those who try to vote but face obstacles in doing so, and those who do not vote altogether. The evidence-based research we explore pinpoints the myriad ways that economic and racial inequality together subvert our democracy by aiding and abetting political inequality and voter suppression."

2. After a very, very rocky initial start, the augmented Unemployment Insurance benefits system in the United States has, in many states, worked very well during the coronavirus recession. Without it the economic disaster, and likely the pandemic disaster, would have been significantly worse. I remain puzzled about the form unemployment has taken over the past year. Why are initial claims still so large? Exactly who and why is being fired in such large numbers right now? Check out Equitable Growth's Unemployment Insurance graphics, "For the week ending January 30."

Worthy reads not from Equitable Growth:

1. The data underlying this observation from Noah Smith are the reason that I have considerable sympathy for the "mismeasurement" theories about the growth of total factor productivity since 1973. I do not know about you, but the nondurables and services that I consume are substantially transformed from those I consumed back in 1973 in a very good quality- and sophistication-adjusted way. There is no comparison between TV dinners now and TV dinners then, between home-produced coffee now and home-produced coffee then, between information and entertainment technologies now and information and entertainment technologies then. What picture of the changing shape of technology can we hold in our minds' eyes that generates extraordinary technological advances in the production of durables, extraordinary quality augmentation in the commodities we consume, extraordinary transformation of our information and information-related technologies, and yet non-durable and service TFP stagnation? My first reaction is: there is none—the process of producing durables overlaps a lot with the process of producing nondurables and services. The difference is that with durables we can better measure quality changes because the old versions hang around for generations with market valuations attached. Now I am not sure that this position is right. And certainly the consensus of those who study these issues carefully and are not fascinated by technology is otherwise. But it does make me wonder. Read Noah Smith, "About that TFP stagnation," I which he writes: "Wow! If you look only at the durables sector, there was no Great Stagnation at all … Durables TFP has been growing more strongly post–1993 than it ever did in the post-WWII boom! Consider this: In the 26 years from '47 to '73, durables TFP nearly doubled, but in the 15 years from '94-'09, durables TFP more than doubled … Something big did happen to technological progress … not in 1973 … but a decade earlier. In the 15 years to 1963, the two sectors progressed pretty much in tandem. But sometime in the early- to mid–60s, they diverged wildly, with nondurables [and services] TFP rising anemically through the late 70s and then basically flatlining until now … I think we should look at the "Great Stagnation" as a more subtle phenomenon than simply the exhaustion of the "low-hanging fruit" of nature. Our technologies for producing durable goods are improving faster than ever."

2. I think that this is 100 percent correct. There is now effectively zero net cost to moving to net-zero CO2 emissions in the United States over the next generation. And we could—and should—do it more rapidly and incur some costs. The benefits to the world will be greatly worth it. Read James H. Williams and his co-authors, "Carbon‐Neutral Pathways for the United States," in which they write: "Modeling the entire U.S. energy and industrial system … we created multiple pathways to net zero and net negative CO2 emissions by 2050. They met all forecast U.S. energy needs at a net cost of 0.2–1.2 percent of GDP in 2050, using only commercial or near‐commercial technologies, and requiring no early retirement of existing infrastructure. Pathways with constraints on consumer behavior, land use, biomass use, and technology choices (e.g., no nuclear) met the target but at higher cost. All pathways employed four basic strategies: energy efficiency, decarbonized electricity, electrification, and carbon capture … In the next decade, the actions required in all pathways were similar: expand renewable capacity 3.5 fold, retire coal, maintain existing gas generating capacity, and increase electric vehicle and heat pump sales to >50% of market share. This study provides a playbook for carbon neutrality policy with concrete near‐term priorities."

The post Brad DeLong: Worthy reads on equitable growth, February 2–8, 2021 appeared first on Equitable Growth.

I have been dismissive of many of the folks, mostly progressives, who highlight wealth inequality as a measure of overall inequality. As most of us know, the richest people in the country have gotten a lot richer since the start of the pandemic. (Of course, the story isn't quite as dramatic if we use February of 2020, before the hit from the pandemic, as the base of comparison.) As much as I am not a fan of rich people, this doesn't especially trouble me.

I have never considered wealth a very good measure of inequality for several reasons.

There is also the very important issue of wealth translating into political power. I will get into that at the end of this essay.

The Fluctuating Value of Wealth

We have seen a sharp run-up in the price of stocks, bonds, and other financial assets in the pandemic, as the Federal Reserve Board pushed short-term interest rates to zero and also sought to lower long-term rates. Since the majority of these assets are held by the richest ten percent of households and close to half are held by the richest one percent, this meant there was a huge rise in wealth inequality. Should this bother us?

I would argue no, first because it is hard to disagree with the merits of the policy. The economy went into a steep recession last spring. Low interest rates have helped sustain demand in the economy since the onset of the pandemic. They have encouraged homebuying and new construction. They also encouraged car buying. And millions of people are now saving thousands of dollars in interest payments each year because they were able to refinance their mortgage.

Lower rates also eased the financial situation of state and local governments, who were able to borrow at lower interest rates. They also likely led to somewhat more investment in both the public and private sector. This is exactly the sort of increase in demand we needed in the economy.

Turning more directly to the wealth issue, Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk have more wealth now than would otherwise be the case, because the short-term interest rate is zero and the long-term rate on U.S. government bonds is around 1.0 percent. Let's say that's bad.

Suppose in a year or two, the economy has recovered and the interest rate on long-term bonds is up to something like 3.0 percent. Let's imagine this knocks stock prices down by 20 percent and the price of bonds by even more.[1] Is everyone happy now?

If wealth inequality is the big evil that we want to combat, then we should be celebrating a drop in the stock market that lessens inequality. Perhaps the opponents of inequality will be out there dancing in the street if the market plunges, but somehow I doubt it. Just as a logical matter, you don't get to be upset about a rise in the stock market increasing inequality and not then be happy a fall in the stock market reducing inequality.

For my part, I find it hard to get too upset about fluctuations in wealth that are likely to be temporary. There was not a fundamental change in the structure of the economy that caused the soaring wealth of the last ten months. In all probability it is a temporary fluctuation that will be reversed. (I'm not making stock market predictions, so I'm not advising everyone to go short.)

Wealth as a Measure of Well-Being

If we stacked everyone in the world by wealth, going from richest to poorest, those at the very bottom would be recent graduates of Harvard business and medical school. I'm not kidding. Many of these people have borrowed hundreds of thousands of dollars to pay for their education. Most of them have few, if any assets. This means that on net, they are hundreds of thousands of dollars in the hole.

Should we be concerned about these very poor people? Since they are likely to be earning well over $100,000 a year, and quite possibly over $200,000 a year, as soon as they start work, it is hard to feel terribly sorry for them.

In fact, many of the poorest people by this wealth measure, both internationally and nationally, are recent graduates who have taken out student loans. While many of these recent grads will have trouble paying off their debts, most won't.

The number of people with large negative wealth creates silly scenarios where we can say that Jeff Bezos or Elon Musk has more wealth than the bottom 40 percent (or whatever) of the world's population. That is dramatic, but it also doesn't mean much.

I probably have more wealth than the bottom 20 percent of the world's population. That isn't because of my great wealth, it is simply due to the fact that I have some positive wealth and the bottom 20 percent taken as whole does not.

Even beyond these theatrics, there is still the problem that student debt makes for calculating well-being. Is a 30-year-old college grad with $20,000 in debt worse off than a high school grad with no debt? The college grad almost certainly has much better earnings prospects, with the difference swamping the $20,000 debt, but if we just looked at wealth, the high school grad is much better off.

But even besides this issue, there is also a more general problem of what counts as wealth. Forty years ago, most middle-income workers (especially men), had traditional defined benefit pensions. These pensions could typically guarantee these workers a middle-class standard of living in retirement.

Traditional pensions have largely disappeared, especially in the private sector. This means that if a worker hopes to maintain a middle-class standard of living in retirement, they have to accumulate assets in a 401(k) or some other retirement account.

The money in a retirement account is included in standard calculations of wealth. Traditional pensions generally are not. (We can impute values for these pensions, but this is generally not done in most wealth calculations.) This leads to a story where we would say that a person with a 401(k) is much wealthier than a person with a traditional pension, even if they have no better prospects for retirement income.

Social Insurance as a Substitute for Wealth

The pension issue is only part of the story, social insurance more generally can be seen as a substitute for wealth. In addition to needing wealth to support income in retirement, we also might need wealth to deal with spells of unemployment, unexpected medical expenses, to pay for their children's college and to buy a house. Some people also have aspirations of starting a business, which also requires some wealth.

The extent to which wealth is needed in each of these areas depends on how we structure our system of social supports. As noted, a good Social Security and pension system makes it unnecessary to accumulate a substantial amount of wealth in retirement. In the case of unemployment, if we have a healthy system of unemployment insurance, most workers can be kept whole through stretches of unemployment.

It's also worth noting that the wealth accumulated by middle class people is primarily in their homes. This matters because this wealth is not easily accessible during spells of unemployment. Banks will be reluctant to issue a mortgage or home equity loan to someone who is unemployed. If an unemployed worker is able to borrow at all, they will pay a substantial interest premium on what would be viewed as a risky loan. They would generally be far better off with a strong system of unemployment insurance.

The same story applies with medical expenses. Bankruptcies due to medical expenses are virtually unheard of in Europe. The reason is these countries have national health insurance systems, which protect the vast majority of the population against major medical expenses.

The provision of free or low cost college education also makes it unnecessary to accumulate large amounts of money to pay for their children's education. Even in a system with largely free public education, some people may still choose to pay the additional cost to send their kids to elite private schools. This sort of inequality in educational opportunity is unfortunate, but the better focus for public policy is ensuring that the public system is high quality and affordable.

In the United States, the vast majority of middle-class households are home owners. While this does typically allow them to accumulate some wealth, the fact that ownership is a superior form of housing is largely due to our laws that effectively make renters a type of second-class citizen. In countries with stronger protections for renters, most notably Germany, homeownership rates are far lower.

There is nothing intrinsically desirable about homeownership. People want security of tenure, so they know they can't just be thrown out of their home on the whim of a landlord. They also want protection against unexpected jumps in rents. Both of these protections can be provided in a legal system that treats renters as full citizens. We actually see this to a limited extent in the United States, where some cities, most notably New York, provide strong rental protections. In these cases, we do see many solidly middle-class (and even affluent) people remain tenants for most of their life.

Beyond just making the point that strong systems of public support reduce the need for wealth in many areas, there is also the concrete matter that the instruments for accumulating wealth tend to divert large amounts of money to the financial sector. To just take the most obvious case, the annual fees on 401(k)s are often over 1.0 percent of the fund's value.[2] When the fees from managing individual funds within an account are added in, many people pay close to 2.0 percent of their fund's value to the financial industry each year.

This could mean that a person earning $60,000 a year, who has managed to accumulate $100,000 in a 401(k), is paying $2,000 a year to the financial industry, or more than 3.0 percent of their income. This is money and resources that would be saved if the Social Security system were instead designed to provide them with an adequate retirement income. There is a similar story with wealth being accumulated to meet other needs, such as health care costs and college tuition.

Homeownership may actually be the worst in this respect. The costs associated with buying and then selling a home can easily exceed ten percent of the purchase price. These costs may not be a big deal for a person that stays in the same house for twenty or thirty years, but they are enormous for someone who only lives in a house for two or three years.

If someone buys a house for $300,000 and then sells it two years later for roughly the same price, they will likely pay over $30,000 in realtor commissions, closing costs on a mortgage, title searches and insurance, and other expenses. This comes to $15,000 a year, for expenses that would be completely unnecessary if they had remained a renter through this period. In a society that is structured to favor homeownership, it is understandable that most people would want to be home owners, but we must recognize that homeownership is not inherently good, and it can be very costly for people who are not in a stable employment or family situation.

It is also worth noting that house prices do sometimes fall, as folks who lived through the collapse of the housing bubble should know well. The idea that the wealth people have in a house will inevitably increase is simply wrong.

Policies to support the accumulation of wealth for low and middle-income families will almost always be seen as alternatives to policies for better systems of social support. It is clear that the wealth accumulation track is better for the financial industry. The track of stronger social supports is likely to be better for almost everyone else.

Okay, I left out the need for wealth to start a business. This is a case where it is hard to see a system of social supports providing an alternative, although the opportunity for stable employment and protection from unexpected medical expenses and the need to save for retirement and children's education, should provide opportunities to accumulate some wealth. And, the vast majority of people will actually never try to start their own business.

Taxing Wealth

The huge sums accumulated by the country's wealthiest people have led many progressives to have dreams of the amount of social spending that could be supported with a wealth tax. As I have argued elsewhere, there are serious political, practical, and legal obstacles to implementing a wealth tax. But on this question, there is a more fundamental economic issue.

At the federal level, we need taxes to restrict consumption, not to literally pay the bills. As the Modern Monetary Theory crew remind us, the government can print as much money as it wants. The limit is that if we create too much demand in the economy, it will lead to inflation. So, we tax to reduce consumption, by reducing the amount of money in people's pockets.

If we think of the prospects of reducing consumption with a wealth tax, they don't look very promising. Consider our latest round of incredibly rich people, like Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and Mark Zuckerberg, all of whom have over $100 billion in wealth. While I am sure these people all live very well, I doubt they spend substantially more on their own consumption in a year than your typical single digit billionaire. There are only so many homes you can live in, cars you can drive, trips you take, etc.

This means that if we taxed away 10 percent, 20 percent, or even 50 percent of their wealth, it will have very little impact on their consumption. This means that it will not get us very far in freeing up resources for an expanded social welfare state. We will not be able to pay for Medicare for All or free college by taxing away these people's wealth, we will have to focus on policies that reduce the consumption of a far larger group of people.

Wealth and Political Power

Many of the critics of extreme wealth point out the enormous political power that someone like the Koch brothers can wield because of their immense wealth. The point is well-taken. There can be no doubt that extreme wealth is horribly corrupting of the democratic process. This corruption takes place not only, or even primarily, through the political candidates whose campaigns they support, but through the academic institutions and think tanks they establish or support, and the media outlets they own. Many intellectually bankrupt ideas, like trickle down economics, have survived and even thrived because deep-pocketed people were willing to support them in academia, policy circles, and the media.

But this diagnosis of the problem doesn't mean that an attack on extreme wealth is the best solution. Suppose we cut the wealth of the richest 1,000 people in half. They would still be able to exercise a ridiculously outsize influence on the country's politics.

The Koch brothers (or the surviving brother) with $25 billion would still have enough money to support all sorts of right-wing think tanks and issue groups. The same is true for the rest of this group. We don't have a plausible path were we can hope to seriously limit their influence by reducing their wealth in any reasonable time-frame.

To my mind a much more plausible route is to go in the opposite direction by increasing the voice of ordinary people. There are concrete steps that can be taken that go far here. The super-matches for campaign contributions that several cities have put in place and are part of the last Congress's HR1 political rights bill are a great start. These proposals match small dollar contributions by many multiples (HR1 puts the match at six to one) in exchange for candidates limiting their big dollar contributions.

Seattle has gone a step further in giving its residents $75 "democracy vouchers" that can be donated to any candidate who agrees to limits on big dollar contributions. The Seattle model can actually be taken a step further in providing tax credits for people to support journalism and creative work more generally. A modest tax credit applied nationwide, can provide an enormous amount of money to support creative work, including newspapers, radio and television outlets, as well as think tanks and unaffiliated academics. This credit would ideally be put in place nationally, but can be done at the state or even local level, as Seattle has done with its democracy voucher.

This will not allow for average people to outspend the billionaires, but it can ensure that they can have a serious voice in public debates. That is probably the best that we can hope for in the foreseeable future.

Big Wealth is a Big Distraction

To sum up, I would argue that the focus on the enormous fortunes of Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos and others is an enormous distraction. It certainly is not good news to see the already incredibly rich get even richer, but wealth inequality should not be the main focus of progressives. The extent to which they actually drain resources from the economy is not well-measured by their wealth. And, we don't have a plausible path for reining in their political power by reducing their wealth. The more promising path is by increasing the voice of every one else.

[1] Bond prices move inversely with interest rates.

[2] Typically, the insurance company or brokerage house managing a 401(k) charges a fee just to hold your money. That averages around 1.0 percent. However, the individual funds in which people invest their money, such as a stock fund or a bond fund, also have fees. For index funds these fees tend to be low, usually between 0.1-0.2 percent. However, some actively traded funds charge considerably higher fees, sometimes exceeding 1.0 percent.

The post Wealth Inequality: Should We Care? appeared first on Center for Economic and Policy Research.

There's an old grim joke about those who hold multiple jobs

Comment: "Hey, did you hear the US economy created 100,000 new jobs last month?"

Response: "Yeah, I'm doing three of them."

Holding multiple jobs isn't always a bad thing: for example, a number of doctors technically have have one job at a private practice and another when they work at a hospital. But in the past, it has been hard to find detailed or consistent evidence on multiple job-holders. For example, household survey data often asks about one's main job, not about all jobs.

Keith A. Bailey and James R. Spletzer of the US Census Bureau Have cracked this problem by finding a way to use data from the Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics (LEHD). The Census Bureau has published a readable short overview of their work in "Using Administrative Data, Census Bureau Can Now Track the Rise in Multiple Jobholders" (February 3, 2021). The full working September 2020 working paper, "A New Measure of Multiple Jobholding in the U.S. Economy," is at the Census Bureau website, too.

The LEHD is based on data that the government was already collecting for other purposes: for example, data on employment that was being collected for the unemployment insurance program, or data from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, and other sources However, this data was often collected for administrative purposes (like running unemployment insurance), and so the task of the LEHD is to pull together data from a variety of sources into an anonymized dataset that can be used by researchers.

Here are some basic findings from Bailey and Spletzer: About 7-8% of the workforce holds multiple jobs, with the share tending to rise when the economy is going well and fall during recessions. The share of people holding multiple jobs seems to be edging up over time, but slowly.

Some other patterns:

Women hold multiple jobs at a higher rate than men and the rate has increased in the last 20 years. In the first quarter of 2018, 9.1% of women and 6.6% of men were working more than one job. ...A basic lesson here is that those with multiple jobs depend fairly heavily on those jobs, in the sense that a quarter or more of their income comes from the additional jobs. One suspects that many of these workers are putting in a lot of total hours, but with limited access to many of the common benefits of full-time jobs like paid vacation, employer-provided health insurance, and contributions to a retirement account.

[M]ost multiple jobs are clustered in a few industries. Here's the percentage of second jobs by sector:Full-quarter jobs are long-lasting, stable jobs that exist in the previous quarter, the current quarter and the following quarter. Multiple jobholders earn less. ... Why do persons with multiple jobs earn less, on average, from all jobs compared to persons with only one long-lasting, stable job? Our working paper shows that this earnings differential is due to age, gender and the industries that employ multiple jobholders. ...

- 16.8% in healthcare and social assistance.

- 16.7% in accommodation and food services.

- 14.5% in retail trade. ...

On average, earnings on all multiple jobs account for 28% of a multiple jobholder's total earnings ($3,780 divided by $13,550). ...

One of the most striking findings is that the share of total earnings that come from multiple jobholding is above 25% for every percentile.

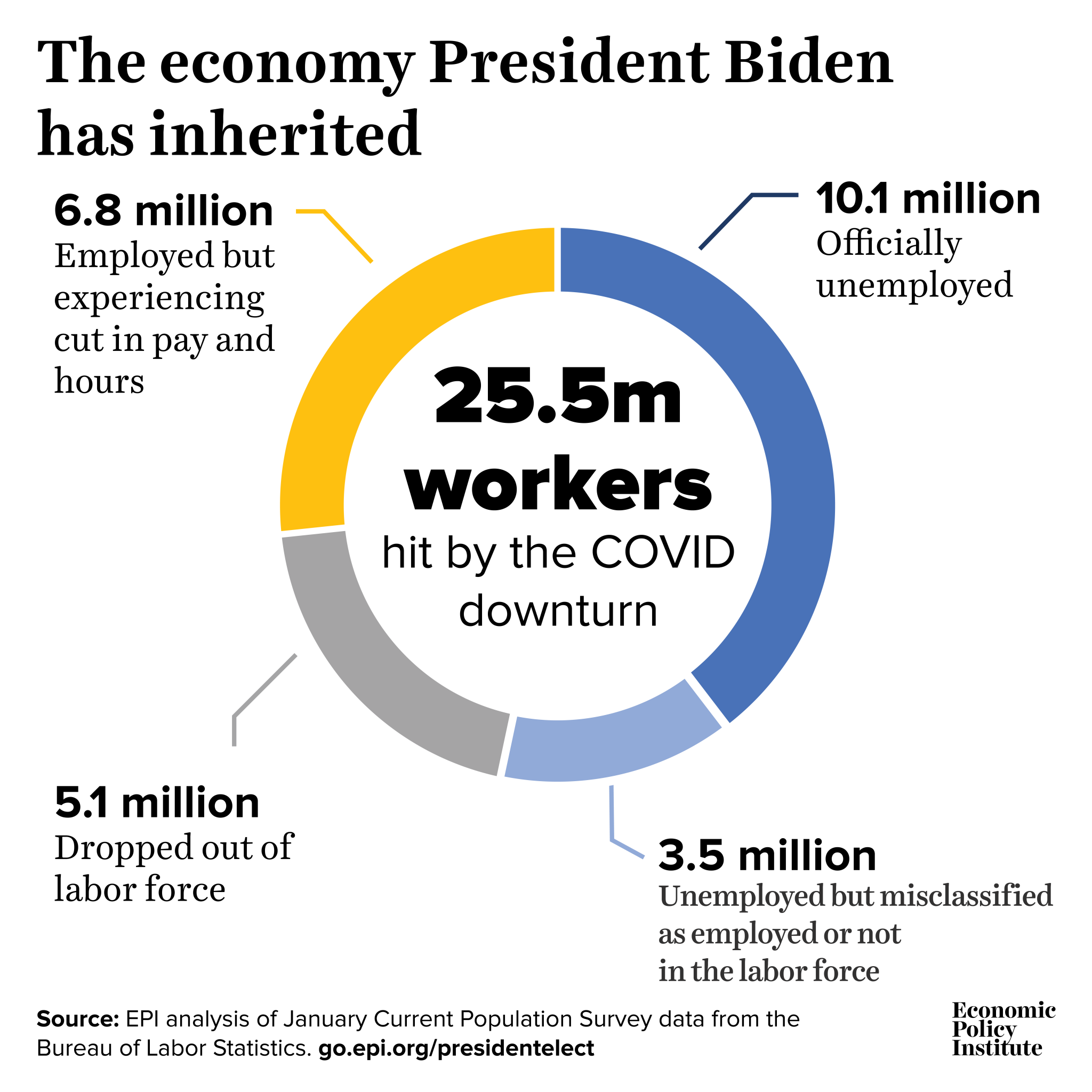

The official unemployment rate was 6.3% in January—matching the maximum unemployment rate of the early 2000s downturn—and the official number of unemployed workers was 10.1 million, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). However, these official numbers are a vast undercount of the number of workers being harmed by the weak labor market. In fact, 25.5 million workers—15.0% of the workforce—are either unemployed, otherwise out of work due to the pandemic, or employed but experiencing a drop in hours and pay.

Here are the missing factors:

Adding up all but the last quantity above, that is 10.1 million + 0.8 million + 2.7 million + 5.1 million = 18.7 million workers who are either unemployed or otherwise out of the labor force as a result of the virus. Accounting for these workers, the unemployment rate would be 11.0%. Also adding in the 6.8 million who are employed but have seen a drop in hours and pay because of the pandemic brings the number of workers directly harmed in January by the coronavirus downturn to 25.5 million. That is 15.0% of the workforce.

Finally, even the 25.5 million is an undercount. For one, it doesn't count those who lost a job or hours earlier in the pandemic but are back to work now. The cumulative impact would be much higher. But perhaps more importantly, the 25.5 million is a drastic undercount because it ignores the fact that even workers who have remained employed and have not seen a cut in hours and pay are being hurt by the weak labor market. How? Essentially the only source of power nonunionized workers have vis-à-vis their employers is the implicit threat that they could quit their job and take another job elsewhere. Case in point: One of the most common ways nonunionized workers get a wage increase is by getting another job offer for higher pay—they either accept the new job, or their current employer gives them a raise in response to their outside offer. When job openings are scarce, as they are now, workers' leverage dissolves. Employers simply don't have to pay as well when they know workers don't have as many outside options.

All this means that providing fiscal aid to the economy is crucial—both to the 25.5 million workers who are being directly harmed by the downturn because they are either out of work or have had their hours and pay cut, and to the millions more who saw their bargaining power disappear as the recession took hold.

A further reason more relief is so important is that this crisis is greatly exacerbating racial inequality. Due to the impact of historic and current systemic racism, Black and Latinx workers have seen more job loss in this pandemic and have less wealth to fall back on. To get the economy back on track in a reasonable timeframe, we need policymakers to pass an additional roughly $2 trillion in fiscal support. President Biden has been pushing for a relief and recovery package that gets the economics right. His proposal is at the scale of the economic challenge we are facing and is a clear break from the mistakes we have made in past recoveries, when we hobbled the economy by not doing enough. With their slim majority in the Senate, Democrats can now get crucial relief measures through reconciliation, and they must be bold. Top priorities must be vaccine distribution measures, aid to state and local governments, and further extensions of unemployment insurance. There is no time to lose.

A survey of West Virginia GDP by industrial sectors for 2022, with commentary This is content on the main page.