https://equitablegrowth.org/the-wage-divide-for-black-and-latinx-workers-goes-deeper-than-a-skills-gap-or-requiring-more-credentials/

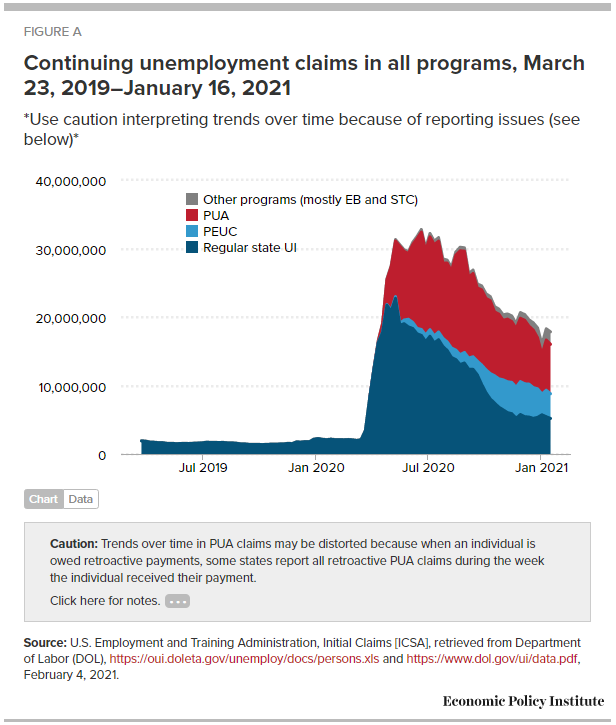

The coronavirus recession continues to severely impact Black and Latinx workers, who are disproportionally suffering, compared to other workers in the United States. These more marginalized workers are registering higher rates of unemployment and lower rates of Unemployment Insurance recipiency. Black and Latinx workers also are reporting a higher proportion of lost income since March and are facing more difficulties paying weekly expenses.

This outsized impact of the coronavirus recession on Black and Latinx workers threatens to reentrench racial and ethnic wage divides in the U.S. workforce, particularly because downward pressure on wages for the most severely impacted groups of workers will continue while unemployment remains elevated. Understanding the causes of these disparate impacts is critical to designing policies that leverage political will to reduce longstanding systemic racism.

The harm caused by the false 'skills gap' narrative

One dominant false narrative that continues to dominate policy discussions is the so-called skills gap—a largely unfounded explanation for the present wage divide in the U.S. economy that poses a serious risk to the efficacy of relief and stimulus policy proposals. This false narrative is based on the correlation between technological advancement, the skill levels of workers needed to translate those advancements into increased productivity, and rising income inequality.

To be sure, at one time, the skills gap was a "stylized fact," economic parlance for a generally accepted explanation of a larger part of specific wage trends. From 1980 to 2000, there was an economywide correlation between schooling and wages, which upheld the "skill-biased technical change" theory and informed policy priorities for the labor market. But this empirical relationship broke down between 2000 and 2017. Yet the skills gap narrative still undergirds policy proposals, placing the onus on workers for stagnating wages despite evidence on the relationship between declining worker power and income inequality.

In particular, promoting the skills gap in policy encourages Black and Latinx people to use their own minimal resources to invest in education and workforce development, disproportionately taking on debt to do so, without any guarantee that it will translate into higher wages and better job quality. These policies do not account for the historical wealth disparities fostered by systemic racism that crushed the ability of Black and Latinx families to build their own wealth over generations.

Despite this glaring wealth handicap, educational attainment increased across all racial and ethnic groups over the past 20 years. Yet the wage divide between Black and White workers worsened over the same time period. Indeed, the racial wage gap is greater at higher levels of education. At the same time, Black college graduates owe more student debt at graduation, and these differences in debt grow over the following years.

Similarly, wage inequality is persistent for Latinx workers, compared to White workers. When comparing Latina workers to White men workers, a larger portion of the wage gap is unexplained, or interpreted as the result of pay discrimination, compared to the gender wage divide between all women and all men. Latinx families also have lower levels of wealth, compared to White families, and this wealth gap persists even when accounting for factors such as education and income level and has widened since the Great Recession of 2007–2009.

The false promise of 'credentialism'

Then, there is the largely misplaced focus of bridging the wage divide via a narrow definition of skills through "credentialism," the theory that workers can improve their job prospects by earning, for example, a bachelor's degree. Credentialism often obscures the skills and familiarity with certain tasks that workers already bring to their jobs and ultimately constrains the mobility of workers with the skills but without the traditional signals, such as workers without a bachelor's degree.

A recent working paper details the skills acquired by workers without these signal credentials. "Searching for STARS: Work experience as a job market signal for workers without bachelor's degrees" is by Byron Auguste, Papia Debroy, and Shah Ahmeh of Opportunity@Work, along with Peter Q. Blair of Harvard University, Tomas Castagino of Accenture Research, Erica Groshen of Cornell University, and Fernando Garcia Diaz and Cristian Bonavida of Accenture Research. They examine the link between narrowly defined education levels and actual job skills to unpack how credentialism contributes to rising wage inequality and job polarization.

Using the O*NET dataset on skills profiles of occupations, the authors develop a skills vector for occupations and measure the "distance" between occupations based on the skills makeup of each occupation. This allows them to reasonably estimate how skills in one occupation could translate into those needed for other occupations, and how this correlates with earnings levels within occupations and the potential for upward income mobility if workers are able to use the skills from their work history to match into higher-paid jobs.

In their paper, they use the example of the brickmasters, blockmasons, and stonemasons occupations and welding, soldering, and brazing occupations, both of which are among some of the most similar occupations within their schema. They find that the metalworking jobs pay nearly twice as much as the stone-working ones. The authors suggest this disparity demonstrates incomplete information about skills applicability across occupations in the labor market and may provide a tool for improving pathways for nonbachelor's-degree workers.

An important race- and gender-based finding of the "Searching for STARS" working paper is that upward job mobility for nonbachelor's-degree workers is also correlated with race and gender beyond what can be explained by variation in skills between different occupations within their vector schema. Higher-earning nonbachelor's-degree workers are disproportionately White men, and those in low-wage occupations are disproportionately women of color. The authors note the "social, historical, and market factors that drive pay bands for some professions," as this occupational segregation by race, ethnicity, and gender and the low minimum wage further compound the wage inequities that Black and Latinx workers experience and prevent them from matching into higher-paying jobs.

How to correct the wage divides in the U.S. economy

The way in which these researchers developed their schema and disseminated their findings is a first step toward ensuring all workers are able to match into jobs well-suited to their skills and allowing for upward income mobility. The second step in their paper suggests that posted job requirements, especially for jobs in newer occupations, may also reflect employer beliefs and practices that do not track with the actual skill requirements of those jobs, which can lead to the higher demand for college degrees. For instance, they find that only 42 percent of workers ages 25 to 34 have at least a 4-year college degree, yet 74 percent of new jobs from 2007 to 2016 were in occupations where employers typically require a 4-year degree.

The authors note that many of these new jobs are in occupations, such as enterprise software application developers and administrators, where college degrees are often required but the skills needed for the job are often learned through experience and targeted training. Indeed, one of the challenges to upward wage mobility that the paper identifies is employers' "rational ignorance" about the skills of nondegree holders, which contributes to the practice of requiring academic degrees for many of these new jobs.

Instead of requiring large shares of the workforce to complete formal education programs that are not necessary for developing the skills on a job, the authors suggest that "in practice, relaxing many current occupational education requirements for a college degree may be another, preferable way to match demand with supply over the coming decade."

In addition, the findings and analysis in the "Searching for STARS" working paper highlight the importance of raising job quality and wages for all workers. This is necessary both to reduce economic inequality and drive more equitable growth because many jobs with lower wages do not reflect their level of skills or broader contributions to society. For instance, child care workers in New York state with average hourly wages of $10.29 might be able to increase their earnings in a higher-paying job with an overlapping skill set, such as a customer service representative ($30.53/hour) or bartender ($38.13/hour), but this highlights the need to raise wages and improve job quality for child care workers, who are essential to building a robust and high-quality early care and education system.

The main conclusion of "Searching for STARS" working paper is that increasing college attendance is not a silver bullet for addressing years of job polarization and wage stagnation. Furthermore, other research demonstrates that it is not the skills gap that is the primary cause of wage inequality over time. Many workers already have skills applicable to a variety of occupations but face constraints matching into those jobs. This mismatch is due both to imperfect information in the labor market, as well as barriers that workers face when searching for work. This is particularly the case for Black and Latinx workers because of persistent hiring discrimination along the lines of race and ethnicity.

The STARS vector is a useful tool for addressing the gaps in U.S. labor market information that lead to lower wages for workers without a college degree. But its success would require a way to both signal this information to employers and ensure that employers use this information in hiring decisions, while also addressing deeper systemic barriers such as hiring discrimination. To ensure that skilled, productive, socially beneficial jobs are well-remunerated also requires increasing worker power so that workers can bargain for and command earnings that reflect the value they bring to the U.S. economy and society.

-- via my feedly newsfeed