Employer concentration suppresses wages for several million U.S. workers: antitrust and labor market regulators should respond

Overview

Introductory economics textbooks often feature perfectly competitive labor markets, where a large number of identical firms compete to hire identical workers, and switching jobs, hiring and firing workers, and creating new job vacancies is easy and costless. In a perfectly competitive labor market, workers are paid wages equal to the marginal product of their labor.

But real-world labor markets are not like this. A large body of evidence in the labor economics literature recognizes that jobs differ on a variety of characteristics besides pay, among them skill requirements, tasks, credentials, benefits, hours, work environment, and coworkers. Workers also differ in how much they value these different characteristics. And the process of matching workers to jobs is time-consuming and expensive for firms to find, screen, hire, and train workers, and for workers to search for and apply for jobs.

All of these factors—differentiated jobs, heterogeneous worker preferences, and search frictions—mean that every labor market is intrinsically characterized by a baseline level of monopsony power, where firms have the ability to set wages below workers' productivity.

On top of this baseline level of monopsony power, other factors can further reduce the degree of labor market competition. One important factor is employer concentration. This is the phenomenon where a labor market has only a few large employers. If there are fewer employers, then workers have fewer options to choose from for a job, which limits competition for their labor and gives employers outsize power over workers' pay.

In the past, employer concentration was often thought to be a niche issue, confined to a few factory towns or rural hospitals. But, in more recent years, a number of researchers have documented higher-than-expected employer concentration across large swathes of the U.S. labor market. These scholars, among them Jose Azar of IESE Business School, Ioana Marinescu of University of Pennsylvania, Marshall Steinbaum of University of Utah, Efraim Benmelech of Northwest University, Nittai Bergman of Tel Aviv University, and Hyunseob Kim of Cornell University, also find evidence that local labor markets with higher employer concentration have lower average wages, suggesting that employer concentration might be suppressing wages by increasing employers' monopsony power.

In a new Washington Center for Equitable Growth working paper, Employer Concentration and Outside Options, co-written by me and Gregor Schubert of Harvard University and Bledi Taska of Burning Glass Technologies, we present a new way to estimate a causal effect of employer concentration on wages. In this issue brief we outline our approach to causal estimation and a new data set we use to define workers' labor markets, and present our findings that employer concentration reduces wages for a significant subset of U.S. workers, predominantly those in low outward-mobility occupations and lower-population areas. We then close with a discussion of possible policy responses, including increased antitrust scrutiny of labor markets and increased use of policies that raise wages directly (such as minimum wages or empowered unions), as part of a broader agenda to tackle the wage suppressive effects of monopsony power.

How to measure the effects of employer concentration

While it seems plausible that employer concentration might matter for workers' pay in theory, it is more difficult to estimate how much it matters in practice. Why? One of the biggest difficulties is discerning the degree to which there is a causal relationship between employer concentration and wages. Collecting data on employer concentration and wages enables researchers to observe that labor markets with higher employer concentration also tend to have lower wages on average. But this negative relationship could be driven by changing local economic conditions that affect both concentration and wages, rather than being a result of concentration causing lower wages.

Imagine, for example, a situation where a local labor market is in decline, with falling productivity and businesses shrinking or closing. A quick look at the data for this local labor market would tell economists that employer concentration is rising and pay is falling, but the fall in average pay might be caused by the decline of the labor market in general and not by the rise in employer concentration. This kind of argument drives substantial skepticism around the idea that employer concentration might be affecting workers' pay in a meaningful way.

In our new working paper, my co-authors and I try to address this problem using a new way to estimate a causal effect of employer concentration on wages, building on the cutting-edge econometric work on granular instrumental variable estimation by Xavier Gabaix of Harvard University and Ralph Koijen of University of Chicago, and on shift-share instruments by Kirill Borusyak of University College London, Peter Hull of University of Chicago, and Xavier Jaravel of the London School of Economics. These econometric tools enable us to identify changes in employer concentration across local labor markets which are not driven by local economic conditions, meaning that we are more likely to be able to estimate a causal effect of concentration on wages (rather than a simple correlation).

The basic logic of our approach is this—we predict the change in employer concentration in an individual local labor market using changing nationwide hiring behavior of large firms that are active in those labor markets. We assume that on average large firms don't base their national hiring decisions on the local economic conditions in any individual occupation and metropolitan area, which means the changes in local employer concentration that we identify are unlikely to be driven by local economic trends. In econometric parlance, the predicted change in employer concentration that we estimate for each local labor market is plausibly exogenous to local economic conditions and therefore our empirical analyses are less likely to suffer from the bias I discussed above.

A second problem in understanding employer concentration is defining the scope of workers' true labor markets. To understand which jobs are feasible for different workers to move into, we build a unique new data set on workers' occupational mobility patterns, constructed from the resumes of 16 million U.S .workers sourced by labor market analytics company Burning Glass Technologies. We use this data to make sure we consider the full scope of workers' labor markets when estimating the effects of employer concentration on wages. (Our new data on occupational mobility—the most granular of its kind for the U.S. labor market—is publicly available for research use here.)

It is also important to note how we measure employer concentration itself. Different research papers take different approaches. In our paper, we follow previous research in measuring employer concentration with a Herfindahl-Hirschman Index, or HHI, the sum of the squared vacancy shares accounted for by each employer, for more than 100,000 U.S. local occupational labor markets over 2013–2016, using data on firms' job postings from Burning Glass Technologies.

How much does employer concentration matter in the U.S. labor market?

Using the methodology described above, my co-authors and I estimate a large, negative causal effect of employer concentration on workers' hourly pay for a subset of U.S. workers. Our results suggest that more than 10 percent of the U.S. workforce is likely to be in labor markets where pay is suppressed by at least 2 percent as a result of employer concentration, and several million of these workers are in labor markets where pay is suppressed by 5 percent or more. These are not trivial amounts of money. For a typical full-time worker making $50,000 a year, a 2 percent pay reduction is equivalent to losing $1,000 per year and a 5 percent pay reduction is equivalent to losing $2,500 per year.

Who are the people most affected by employer concentration? The most-affected workers tend to be identifiable by three factors:

- They are in occupations with low outward mobility, usually because they have skills that are very specific to their occupation or have invested in training, licensing, or certification, so that it's difficult to find a comparably good job outside their chosen occupation.

- They are in lower-population areas, which matters because there tend to be fewer firms in places where there are fewer people.

- They are in industries that tend to have a high concentration of employers.

Taken together, these factors mean that a very large share of the most-affected workers are healthcare workers in smaller cities (which tend to have highly concentrated healthcare sectors), including registered nurses, licensed practical and vocational nurses, and nursing assistants, pharmacists and pharmacy technicians, and phlebotomists, lab technologists, and radiologic technologists. Another occupation that appears to be strongly affected by employer concentration is security guards, who seem to have most of their employment opportunities at only a few large firms.

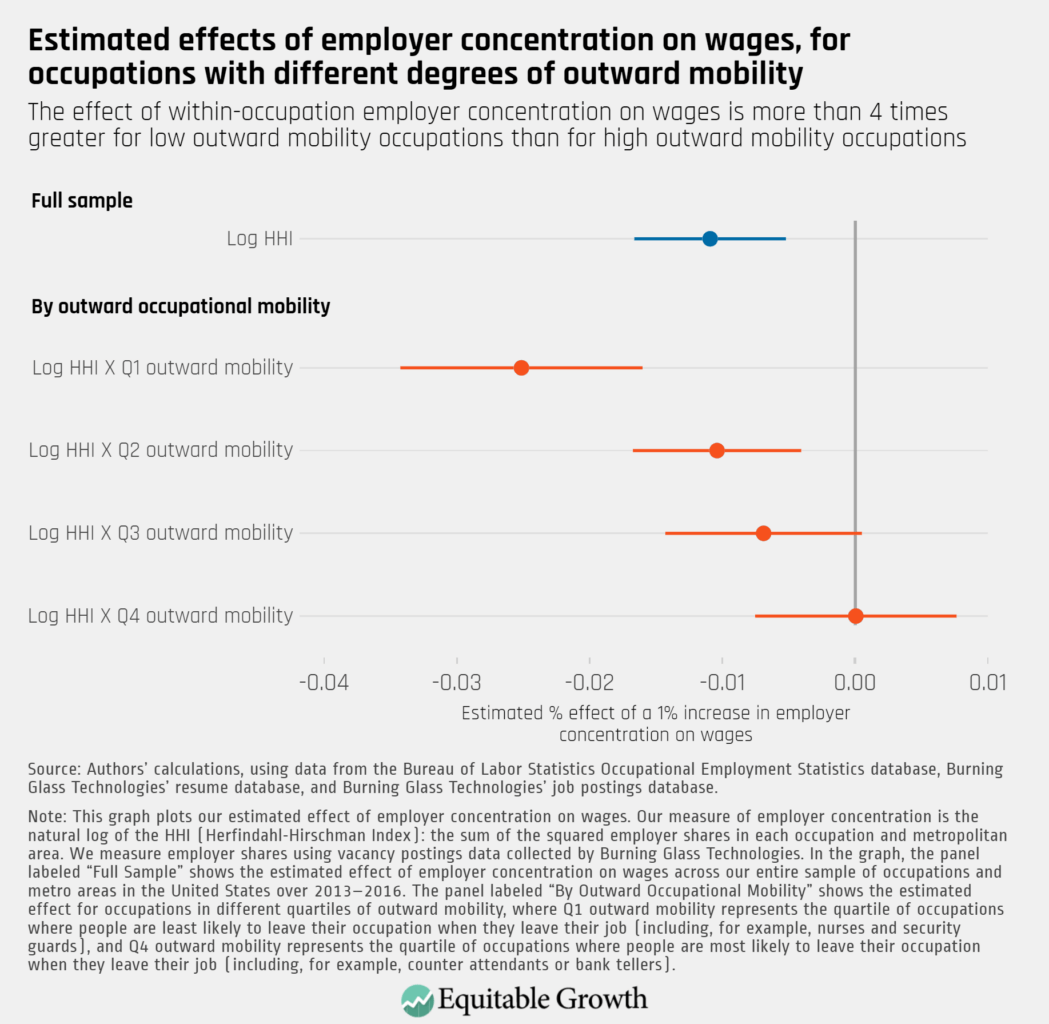

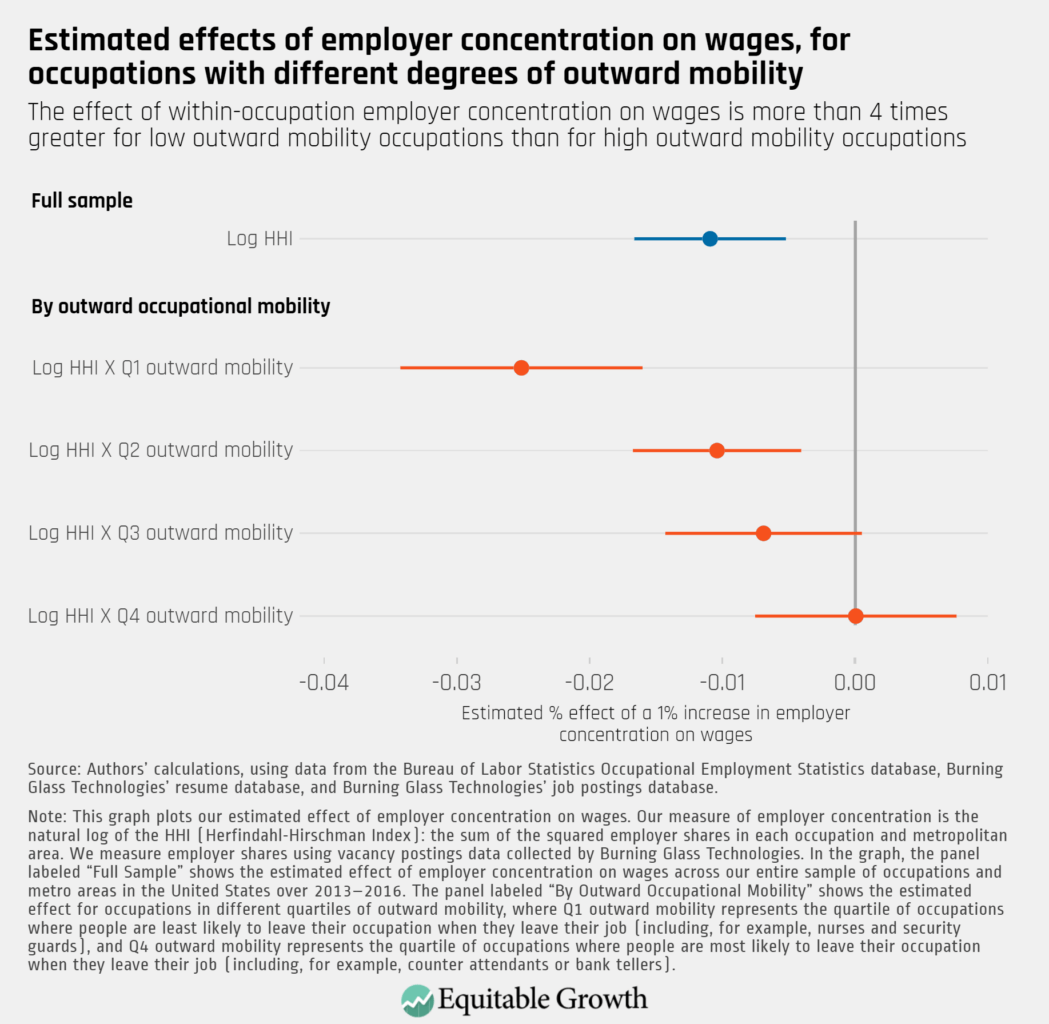

Our paper suggests that a focus on occupational mobility is particularly important. We find that the effect of employer concentration on wages is at least four times higher for workers in occupations with low outward mobility—such as the healthcare occupations or security guards mentioned in the previous paragraph—than it is for occupations with high outward mobility such as bank tellers or counter attendants. For workers in the lowest quartile of outward mobility, our results suggest that moving from the median level of employer concentration to the 95th percentile reduces average hourly pay by between 4 and 8 percent. To put this into context, median annual pay for a registered nurse is $73,300 and for a pharmacy technician is $33,950. So a 4 percent to 8 percent pay reduction would mean roughly $3,000 to $6,000 less income per year for a typical registered nurse or $1,400 to $2,700 less per year for a typical pharmacy technician. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Our research isn't the first or last word on this issue. Each new research paper adds a small piece to an ever-growing collage of research on employer concentration. Elena Prager of Northwestern University and Matthew Schmitt of the University of California, Los Angeles, for example, analyze hospital mergers, finding that mergers which increase hospital concentration to high levels substantially reduce the wages of nurses and other healthcare occupations. And David Arnold at the University of California, San Diego, finds that merger and acquisition activity that significantly increases local labor market concentration leads to an average decline in worker wages of 2 percent.

A number of other papers demonstrate correlations between wages and measures of employer concentration at the level of local occupations and industries, all of which are robust to a large variety of control variables. In addition, Yue Qiu at Temple University and Aaron Sojourner at the University of Minnesota also find that workers in highly concentrated labor markets receive less non-wage compensation in the form of health benefits, and U-Penn's Marinescu, along with Qiu and Sojourner, find that workers in highly concentrated labor markets are more likely to be subject to labor rights violations.

This evidence overall clearly refutes the idea that employer concentration is a non-issue, affecting only a handful of workers in factory towns. Yet it's also worth emphasizing that, by our best read of the evidence, employer concentration is not likely to be an important factor in wage determination for the majority of U.S. workers. Similarly, it seems unlikely that changes in employer concentration can explain more than a small share of the macro-level trends of rising inequality or wage stagnation (as argued in more detail by Kevin Rinz at the U.S. Census Bureau, and by David Berger at Duke University, Kyle Herkenhoff at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and the University of Minnesota, and Simon Mongey at the University of Chicago).

Rather, the bulk of the evidence suggests there is a subset of workers—at least several million across the United States—whose wages are suppressed by employer concentration. These are the workers any policy response designed to mitigate the effects of employer concentration should focus on.

What does this mean for anti-monopsony policymaking?

The policy area where these findings are most directly relevant is antitrust, which is explicitly designed to tackle excessive market power. U.S. antitrust authorities have, until recently, almost never considered labor markets in merger scrutiny or in anti-competitive behavior suits. Over recent years, there have been growing calls for antitrust authorities to increase their role in preventing anticompetitive behavior in labor markets, including the Washington Center for Equitable Growth's own recent report on antitrust.

Two papers in particular—one by U-Penn's Marinescu and Herbert Hovenkamp and the other by Suresh Naidu at Columbia University and Eric Posner at the University of Chicago—argue that antitrust authorities should use employer concentration as a screen for possible anti-competitive effects of mergers and acquisitions, as they already do routinely in product markets. They propose that labor markets where mergers would increase employer concentration beyond a certain threshold would be subject to further, more detailed scrutiny before any decision as to whether the merger should be allowed to go ahead.

Our findings would support this policy move, with one caveat. Our results underscore the importance of the definition of the local labor market for the underlying effect of employer concentration. Marinescu and Hovenkamp argue that in the screening process antitrust authorities should measure employer concentration at the level of individual local occupations, but we find that the effects of employer concentration on wages are more than four times as high for occupations with low outward mobility—such as the healthcare workers or security guards mentioned earlier —than for occupations with very high outward mobility, among them cashiers, bank tellers, or counter attendants.

This finding suggests that antitrust authorities should consider not only employer concentration within a local occupation, but also the possibility for outward mobility from that occupation when carrying out this merger scrutiny. While this is a small tweak to the overall policy direction, it could have important ramifications. Our methodology would suggest that mergers to even relatively low levels of employer concentration for occupations with low outward mobility such as nurses should be a greater concern than mergers which increase concentration to high levels for occupations with high outward mobility, such as bank tellers or cashiers. We give some concrete examples where this might matter in our paper.

Increasing antitrust scrutiny in U.S. labor markets is important and feasible, but it's also important to note that in many cases, increased antitrust scrutiny cannot address the wage effects of employer concentration. This is because very often employer concentration arises not because of M&A activity but rather because of firm growth, which antitrust authorities have less power to do anything about. In these labor markets, other policy tools are needed to address the wage suppression arising from employer concentration.

In addition, and perhaps more importantly, it may not always be desirable to reduce firms' size. If there are economies of scale, large firms may be substantially more productive than small firms: think of a factory that may need a minimum scale to operate with cutting-edge technology. In cases like these, if two firms merge, the productivity gains from the increased scale may be greater than the wage suppression arising from the increase in employer concentration. Indeed, if workers receive higher pay as a result of these productivity gains, then it is quite possible that even as employer concentration reduces wages relative to productivity, pay might be higher in a concentrated labor market than in a counterfactual world where the employers were broken up into smaller firms.

In cases like these, enabling firms to stay large while also ensuring that workers share in the productivity gains of the large firms may be a better solution than breaking firms up or preventing mergers. How might this be done? Roughly speaking, there are two categories of policies. One set of policies raises wages externally: through minimum wages at the lower-income end of the labor market, and perhaps through sectoral or occupational wage boards for workers higher up in the income distribution. See, for example, this proposal by economist Arindrajit Dube at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Another set of policies empowers workers directly to seek better compensation and working conditions, by increasing workers' formal bargaining power, whether through increased support for the firm-level unions that are more common in the United States or through the type of sectoral bargaining between groups of unions and firms which is prevalent in much of continental Europe. For these policies, it is important to ensure that increases in bargaining power designed to provide countervailing power against concentrated employers tackle the issues raised by the fissuring of the workplace and the legal status of independent contractors. See, for example, work by Brandeis University's David Weil and work by Wayne State University's Sanjukta Paul.

Raising minimum wages and empowering unions are, in addition, effective more broadly as a response to all sources of monopsony power in the labor market (not just as a response to the monopsony power generated by employer concentration). And indeed, the greater degree of underlying monopsony power in the labor market, the less likely it is that minimum wage increases or union drives reduce employment: recent work by IESE's Jose Azar, Emiliano Huet-Vaughn at Pomona College, U-Penn's Marinescu, Burning Glass Technology's Taska, and Till von Wachter at the University of California, Los Angeles, for example, finds that minimum wage increases do not have negative employment effects in highly concentrated labor markets.

Finally, workers' vulnerability to employer concentration can also to some extent be reduced by enabling workers to move more easily, both between geographic locations and between occupations. One promising avenue for some occupations may be to increase the degree to which occupational licenses and certifications are mutually recognized across different U.S. states and the District of Columbia: the University of Minnesota's Janna Johnson and Morris Kleiner find that mutual recognition of occupational licensing has a substantial effect on workers' geographic mobility. Another avenue would be increasing housing supply and reducing housing costs in high-wage cities, which would increase workers' ability to move to places with higher-paying jobs: work by Peter Ganong at University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy and Daniel Shoag at Harvard Kennedy School suggests that part of the decline in geographic mobility for low-income workers over recent years can be explained by high housing costs.

Conclusion

Overall, the increased concern over employer concentration from researchers and policymakers is justified. A growing body of compelling causal evidence suggests that employer concentration reduces wages for a non-trivial subset of U.S. workers, particularly those in low-outward-mobility occupations, low-population regions, and highly concentrated industries. Importantly, though, employer concentration does not appear to be a major factor in wage suppression for the majority of American workers.

Still, there is a strong case for substantially increased antitrust scrutiny of labor markets, using employer concentration—measured appropriately to reflect workers' mobility—to screen M&A applications for potential anti-competitive effects. In addition, the growing body of evidence on employer concentration further strengthens the case for a substantial increase in the use of policies that raise wages directly via higher minimum wages, wage boards, and empowered unions as part of a broader agenda to tackle the wage suppressive effects of monopsony power.

—Anna Stansbury is a Ph.D. candidate in economics at Harvard University and a Ph.D. scholar in Harvard's Program in Inequality and Social Policy

-- via my feedly newsfeed