Broad structural change is needed to boost wages in a U.S. economy that is more equitable to produce strong, sustainable economic growth

Overview

The U.S. labor market is shackled by decades of wage stagnation for the majority of workers, persistent wage disparities by race, ethnicity, and gender, and sluggish economic growth. The steady increase of income inequality since the 1970s leaves generations of U.S. workers and their families unable to cope with the daily costs of living, let alone save for emergencies or invest in their futures—conditions that have left many families ill-prepared for the "stress test" of the coronavirus recession.

These labor market ills particularly affect women and workers of color due to decades of gender inequality and structural racism erecting barriers to opportunities. There is increasing evidence that broad structural inequality leads to a misallocation of talent and the undervaluation of different types of work, which contributes to anemic economic growth and slower productivity gains.

Boosting Wages for U.S. Workers in the New Economy

Creating an economy that works for everyone and serves those who are historically marginalized requires addressing underlying economic structures that form the foundation for U.S. labor market policies. These unequal structures entrench barriers to opportunity based on race, ethnicity, and gender, and exacerbate the power imbalances that allow employers to undercut wages and allow gains of growth to accrue to the few while stifling a robust, dynamic U.S. economy.

Existing efforts to address wage stagnation and persistent disparities tend to be limited to two narrow approaches: minimum wages and educational investments. Both are critically important, but neither are sufficient to overcome the unequal structures in the U.S. labor market. Minimum wages reach only the bottom of the wage distribution, while increasing education as a response to stagnating or falling wages at each education level amounts to asking workers to run faster on a treadmill, making little progress against the overall deterioration of worker compensation.

This book, a joint effort of the Washington Center for Equitable Growth and the Institute for Research on Labor and Employment at the University of California, Berkeley, presents a series of essays from leading economic thinkers, who explore alternative policies for boosting wages and living standards, rooted in different structures that contribute to stagnant and unequal wages. The essays cover a variety of strategies, from far-reaching topics such as the U.S. social safety net and tax policies to more targeted efforts emphasizing laws governing American Indian tribal communities and the barriers facing women and workers of color in the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics fields.

These essays demonstrate that efforts to improve workers' access to good jobs do not need to be limited to traditional labor policy. Labor income is still how most Americans achieve security and stability, but the determination of those earnings does not take place in a vacuum. Policies relating to macroeconomics, to social services, and to market concentration also have direct relevance to wage levels and inequality, and can be useful tools for addressing them.

We divide the essays presented in this book into three broad themes:

- Worker power

- Worker well-being

- Equitable wages

Here are brief synopses of each of these themes.

Worker power

In recent decades, worker compensation has failed to keep up with economic growth and productivity. This is, in large part, a reflection of eroding worker bargaining power, which has not been strong enough to ensure that workers receive their fair share of the gains. Decades of declining unionization, poorly enforced labor market protections, and competition policy biased toward corporations have eroded worker bargaining power in the United States. A critical part of boosting workers' earnings is to reverse this erosion and ensure that workers have the bargaining power to claim their share of employer profits.

A first step to boosting wages is making sure that legal protections and statutory minimum wages already on the books are enforced. In their essay titled "Strategic enforcement and co-enforcement of U.S. labor standards are needed to protect workers through the coronavirus recession," Janice Fine, Daniel Galvin, Jenn Round, and Hana Shepherd at Rutgers University's School of Management and Labor Relations highlight novel evidence on the prevalence of wage theft. This occurs when employers violate minimum wage or overtime pay statutes, essentially stealing the wages to which workers are legally entitled.

Unfortunately, workers have little recourse against this wage theft. The enforcement of these laws requires workers to file claims of their own accord, an expensive and risky proposition that is generally out of reach for exactly the groups of workers most at risk of wage theft. Fine and her co-authors propose strategic enforcement for likely violators, such as targeting wage theft investigations for employers in industries with higher rates of wage theft, and co-enforcement with organizations that are more effective at identifying violations, such as worker centers embedded within economically marginalized communities.

But the enforcement of labor standards takes place in an increasingly fissured and global economy. Work is increasingly outsourced from large companies to small contractors, where the large employer may control the work process but can disclaim responsibility for the treatment of workers. This depresses wages and reduces workers' ability to claim the benefits of their productivity.

Economist Susan Helper at Case Western Reserve University discusses what she calls "supply chain dysfunction," or when the outsourced company has little power against the outsourcing company so they must manage supply chain inefficiencies by cutting their own costs, which exerts a further downward pressure on wages. In her essay, "Transforming U.S. supply chains to create good jobs," Helper examines how production is connected across companies and space. She proposes a new industrial policy that addresses the power imbalances of production in the United States. Small companies need to be able to share in the value created by supply chains so they can provide quality jobs, and collaboration and partnership must be promoted, so that supply chain ecosystems across manufacturing and service industries create dynamic and healthy labor markets.

Another, related factor influencing worker bargaining power is the increasing concentration of the economy into a small number of large, dominant employers that are able to exert substantial wage-setting power. In neoclassical models, the fact that many employers are competing for each worker's labor ensures that workers will be compensated in proportion to their contributions, but when employment is concentrated (known as "monopsony"), this assurance falls apart. In "Boosting wages when U.S. labor markets are not competitive," Ioana Marinescu at the University of Pennsylvania's School of Social Policy and Practice reviews the evidence relating labor market concentration to wages, and proposes antitrust enforcement and increasing worker power as two tools to offset the wage-setting power that comes from further concentration.

It is not only microeconomists who are grappling with the growing disconnect between productivity and wages. This is also an important challenge to standard macroeconomic models. In "Collective bargaining as a path to more equitable wage growth in the United," economist Benjamin Schoefer at the University of California, Berkeley reviews the macroeconomic literature on the presumptions and evidence for how the macroeconomy works, and finds various policies that promote worker bargaining power, such as sectoral wage determination, may help workers share in the fruits of their own productivity growth.

The policies in any of these essays work in tandem with fostering worker voice. Growing attention on fostering worker power is evident in initiatives such as the clean slate for worker power agenda from Harvard Law School's Labor and Worklife Program. The proposals in the clean slate agenda would boost the effectiveness of each of the topics in this series, including a pathway toward sectoral bargaining and more protections for workers on-the-job.

Worker well-being

The second group of essays considers ways to improve worker well-being, given existing bargaining relationships. In "U.S. labor markets require a new approach to higher education," economist Andria Smythe at Howard University points to universities—anchors of local economic activity and innovation—as key institutions that can contribute to worker well-being. She demonstrates that broad policies that increase access to education also support the higher education industry, which, in turn, fosters an innovative U.S. economy, creating a virtuous cycle that links individual skill-building to local economic activity to a more equitable U.S. economy across cities and regions of the nation.

Furthermore, Smythe details how accessible higher education tightens labor markets by eliminating the need for students to work while in school, which often both limits their engagement with school and takes jobs that might otherwise go to nonstudents. More accessible higher education would increase demand for workers and increase worker bargaining power.

Another policy approach is to adopt labor market policies that enable workers' compensation to go further. An essay by one of the authors of this introduction, Jesse Rothstein at the University of California, Berkeley, and Columbia University's Sandra Black, titled "Public investments in social insurance, education, and child care can overcome market failures to promote family and economic well-being," demonstrates how rising costs of key necessities, such as higher education and medical and child care, as well as increasing risk faced by workers, erodes worker well-being and thus their effective wages.

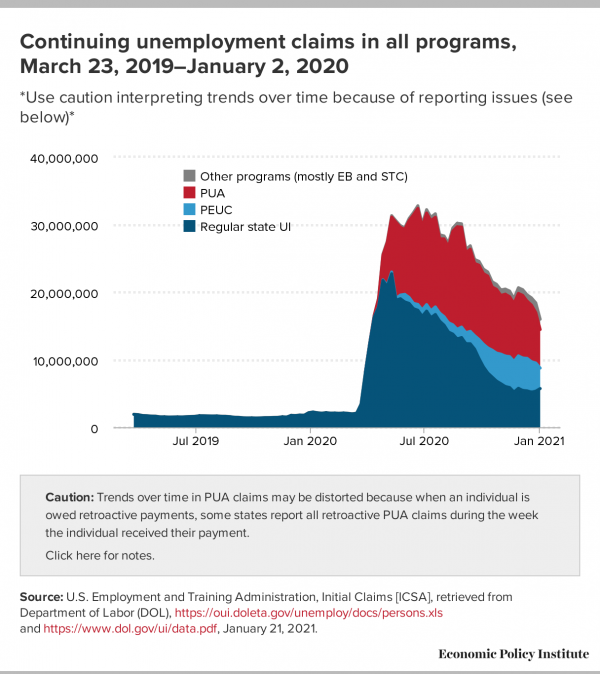

Rothstein and Black argue that the public provision of early childhood education, the alleviation of student debt, and the provision of comprehensive social insurance such as Unemployment Insurance, retirement security, health insurance, and long-term care insurance would all help build the foundation for workers to have a lower cost of living and security to invest in their economic futures. This kind of social safety net would mitigate downside risks while also fostering a more resilient economy, in which economic shocks and business cycles will be less likely to lead to permanent negative consequences for workers and families.

Another aspect of promoting wage growth for workers are tax policies that influence corporate investment and sharing the gains of productivity growth. In an essay titled "Targeting business tax incentives to realize U.S. wage growth," economist Juan Carlos Suárez Serrato of Duke University describes the different ways that corporations respond to tax cuts. Do they take them as windfalls to distribute to shareholders, with no benefit for workers, or do they use them to invest in productivity enhancements that would lead to increased worker compensation? He suggests that the design of the tax cuts influences their allocation, and proposes that tax cuts need to be linked to wage gains for workers to ensure that companies share gains with workers to improve the well-being of their employees and their families.

Equitable wages

The third group of essays considers strategies for reducing wage disparities to create more equitable wage structures across the U.S. labor market for all U.S. workers. A labor market in which workers from historically marginalized backgrounds are able to access equitable opportunities is a labor market that works for everyone.

In her essay on racial and gender inclusion in the so-called STEM fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, titled "Addressing gender and racial disparities in the U.S. labor market to boost wages and power innovation," economist Lisa Cook at Michigan State University demonstrates how marginalized groups, particularly women and Black workers, face barriers at each stage of the innovation pipeline, limiting economic growth and prosperity for all. Cook argues for investments, mentoring support, and other practices to not only open the doors to STEM education and research for underrepresented groups, but also to allow Black and women innovators to share in the gains from their work.

Sociologist Robert Manduca at the University of Michigan demonstrates that a great deal of wage inequality ranges across geographic regions. In his essay, "Place-conscious federal policies to reduce regional economic disparities in the United States," he proposes place-conscious universal policies to address geographic wage inequality. Increasing geographic inequality is exacerbated by deregulation in the transportation and communications industries and by weak antitrust enforcement, which favors increasingly powerful companies and well-connected urban areas. Manduca points out that the enforcement of national antitrust policy is especially important in those locations where there are dominant employers, such as those described in Marinescu's essay. Universal programs, such as a broader social safety net and creating jobs through direct public investment and employment, can help boost wages in communities that have been left behind, increasing economic security for workers and families located in these economically depressed regions of the nation.

This book closes with an essay examining one of the most marginalized groups in the U.S. labor market, Native Americans, who face extremely high rates of poverty and unemployment due to myriad economic, social, and political injustices inflicted over centuries of oppression. In his essay, "Sovereignty and improved economic outcomes for American Indians: Building on the gains made since 1990," Randall Akee at the University of California, Los Angeles reviews the current status of tribal communities across the United States. He considers what is needed to create structures, including improving infrastructure and education, that allow for economic growth and prosperity after centuries of marginalization, oppression, and genocide.

Policies that address structural economic issues in tribal reservations can also impact economic inequality in the surrounding regions, particularly in states in the West and Southwest, where American Indians make up larger shares of the population. Akee writes that the specific historical and cultural context of tribal sovereignty is a critical aspect of boosting wages for workers from these communities. He also calls for improving outcomes in tribal communities by improving data collection and researching the barriers to economic development.

Worker empowerment matters for all policies

A theme that runs across all of these essays is that worker empowerment is crucial to ensuring wage equality and financial security across the U.S. labor market. The essays provide a set of roadmaps for encouraging wage growth and reducing wage inequality by the creation of underlying economic structures that allow workers, particularly those who face the greatest barriers, to advance in their careers, contribute to productivity growth, and share in the gains of a robust and resilient economy.

As the U.S. economy eventually recovers from the coronavirus recession and progresses into another period of economic growth, the policies developed by top academics in this series of essays provide a pathway for more equitable growth. Dealing with the baleful economic consequences of economic inequality now, which the current pandemic has laid bare, would result in stronger and more sustainable economic growth in the years and decades ahead.

-- via my feedly newsfeed