https://equitablegrowth.org/the-long-run-implications-of-extending-unemployment-benefits-in-the-united-states-for-workers-firms-and-the-economy/

At the outset of the coronavirus pandemic earlier this year, millions of U.S. workers lost their jobs. In March, the U.S. Congress took notice and decided that the 26 weeks of Unemployment Insurance typically provided by states were not enough for an employment crisis that would likely extend beyond 6 months. Through the new Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation program, it provided people who lost jobs through no fault of their own with an additional 13 weeks of benefits.

Today, coronavirus cases counts are skyrocketing, hospitals are filling, businesses are closing, and long-term unemployment is surging. But some workers have already run out of benefits, and the PEUC program is set to expire on December 26, leaving 8.1 million workers without any income support through this emergency 13-week benefit extension.

The expiration of the Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation program means devastation for workers and their families this December. But research released earlier this year by Adriana Kugler and Umberto Muratori at Georgetown University and Ammar Farooq at Uber Technologies Inc. shows that the effects of the PEUC expiration are likely to persist far into the future for workers whose benefits expire, and ripple through the U.S. economy to affect firms and workers searching for well-matched employment relationships.

The basic idea behind this research is intuitive. When people have resources to meet their basic needs while out of work, they can take the time they need to find the right job for them, rather than taking the first work opportunity that comes along. Workers benefit because they find jobs that pay more and meet their needs more broadly, and firms benefit because they recruit workers with the right skills for the job. While the idea makes sense, it hasn't been backed by much evidence in the U.S. context, in part because of data limitations.

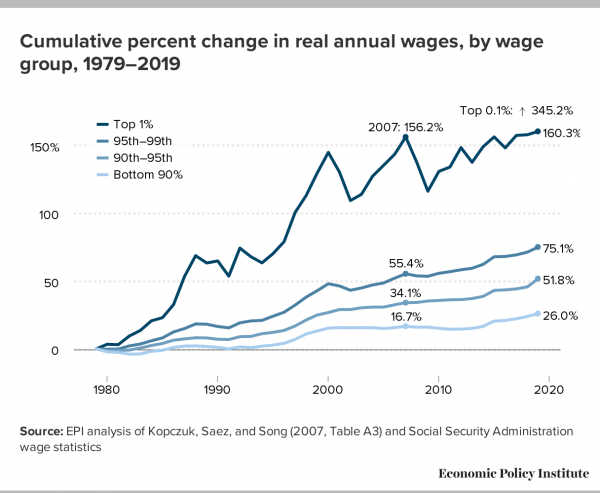

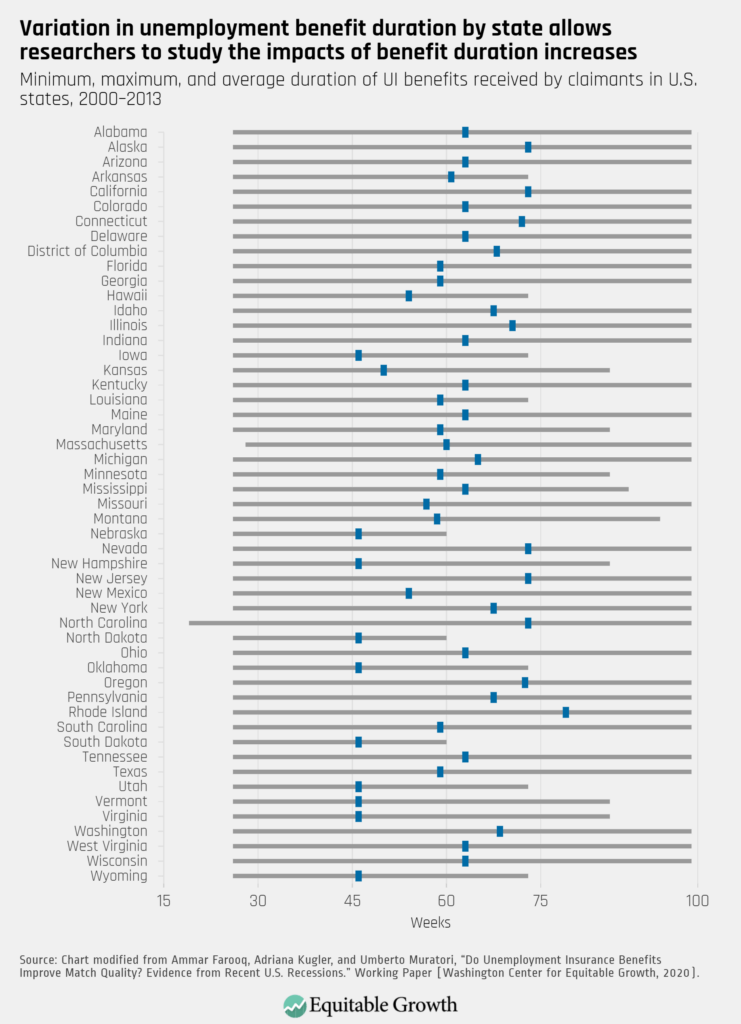

This makes it particularly exciting that this research team was able to access data from the Longitudinal Employer Household Dynamics database, which matches administrative information about workers and their earnings with administrative information about their employers. Using these data, as well as information from the Current Population Survey and the natural experiment that occurred when different states offered different durations of unemployment benefits during the Great Recession of 2007–2009 and its aftermath, Farooq, Kugler, and Muratori take a close look at how job seekers and firms fare when the duration of unemployment benefits is extended. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

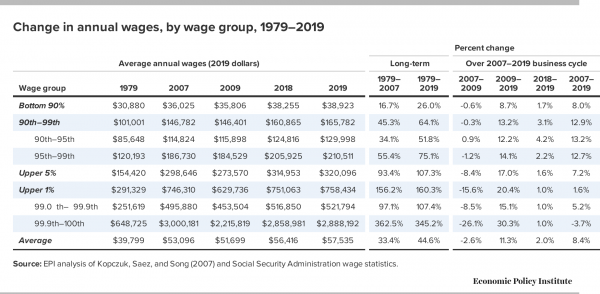

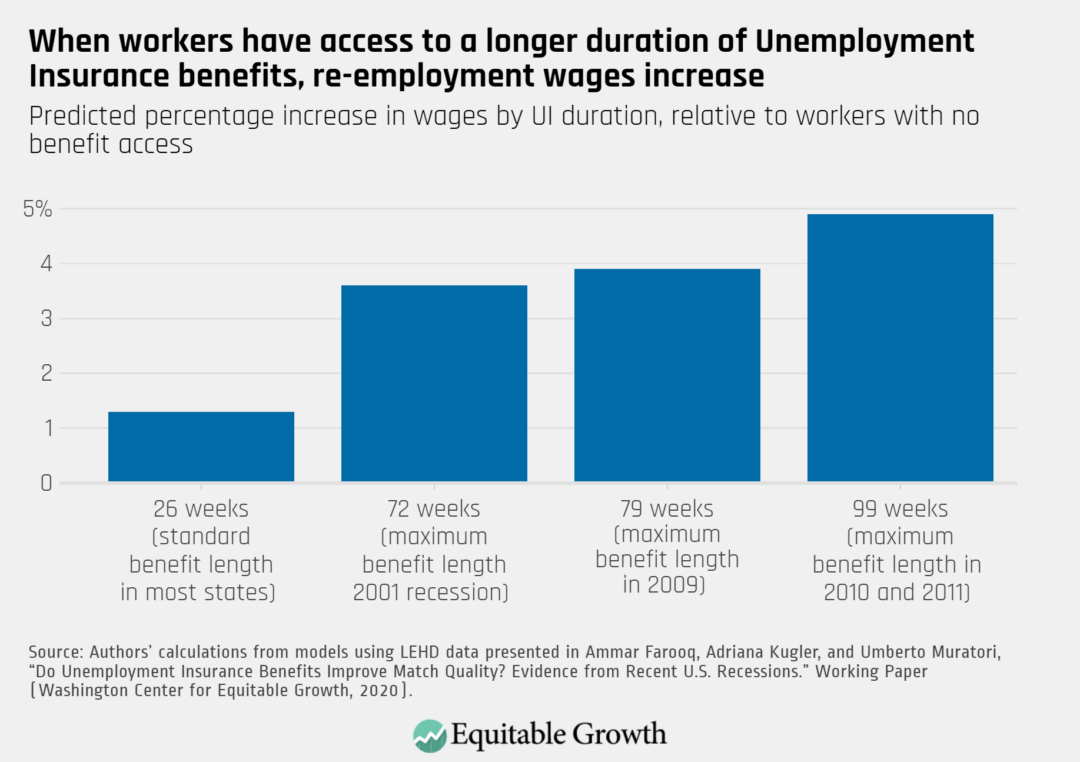

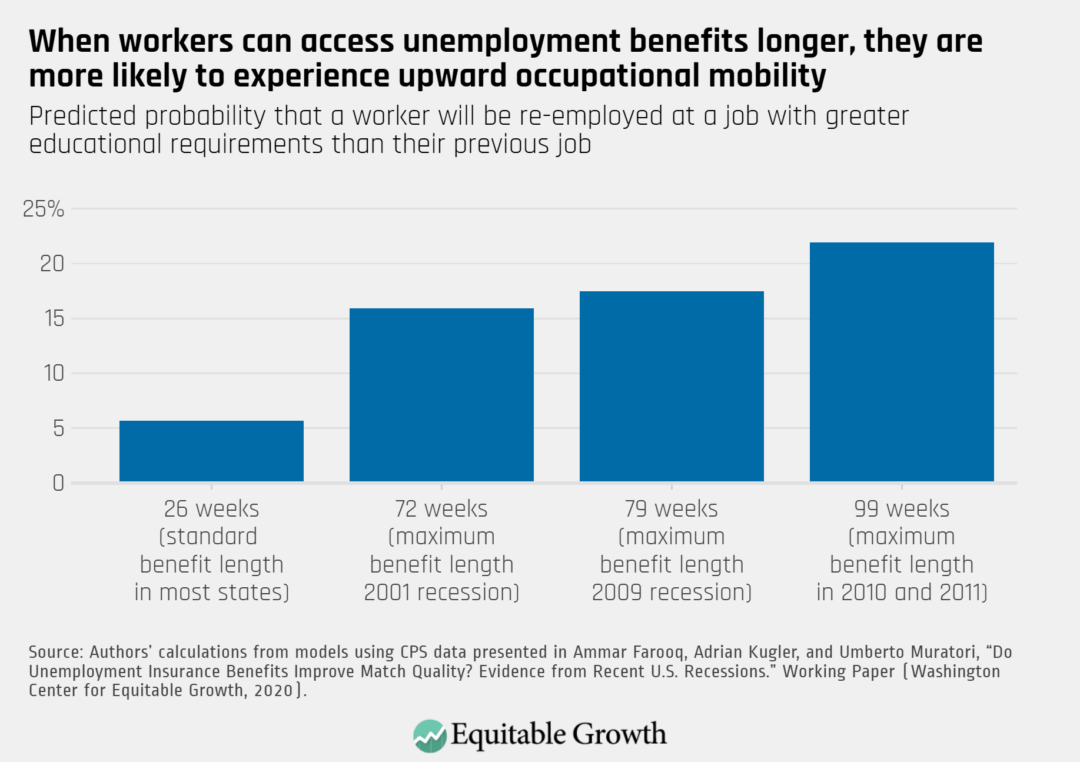

Farooq, Kugler, and Muratori find that the longer you have access to unemployment benefits, the higher paying the job that you eventually find is and the more your skills and training get put to use. (See Figures 2 and 3.) Access to the full extended emergency benefits during 2009, which increased benefits from 26 weeks to 79 weeks, increases re-employment wages by 2.6 percent and also increases the probability that a worker will be re-employed in a job that requires more education than their previous job by 11.7 percentage points.

Figure 2

Figure 3

The idea that workers match their talents with job openings that put their skills to use is not just good news for those workers. It matters for firms and the broader economy as well. Farooq, Kugler, and Muratori take advantage of their dataset, which allows them to follow individual workers over time and also to see the full workforce of the firms with which they eventually find re-employment. Using these features of the data, they find that higher-quality firms are better able to recruit workers that have the abilities they need. This creates a chain reaction that spreads through the U.S. economy. The authors describe it eloquently:

These results suggest that if a worker can receive UI benefits for a longer period, she will be able to find a job with an employer that is closer to her in terms of quality. This worker then is likely to leave another job open for someone else who is also likely to be better matched, and in turn that other worker can also leave vacant another job and relieve it to someone else, generating a chain reaction that makes many other workers, beyond the one receiving the UI extension, match better in the labor market.

In this manner, the benefits of extended unemployment benefits ripple past a worker's current situation to affect their future job prospects, the productivity of firms, and the experiences of workers across the economy.

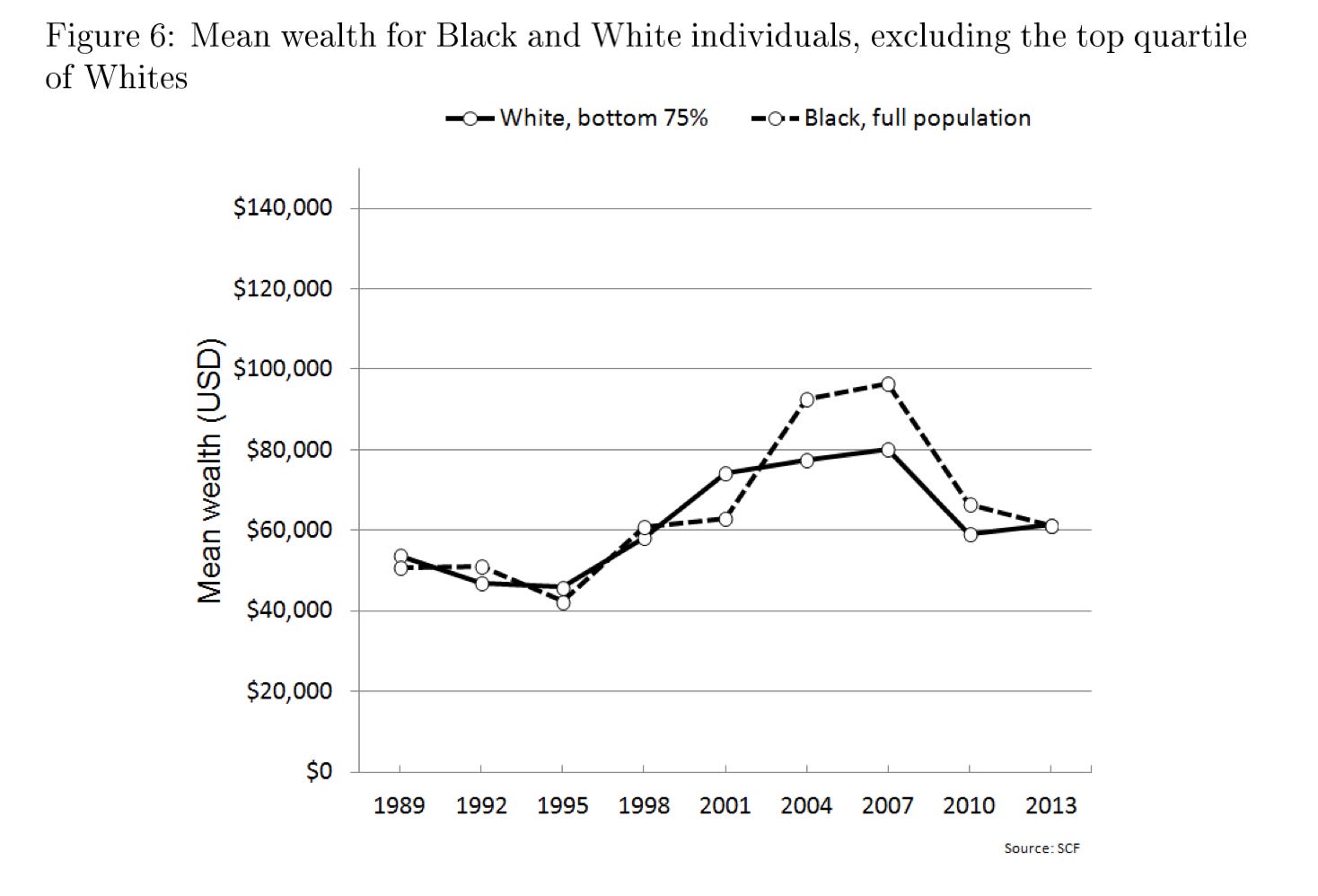

Particularly striking is the fact that the positive effects of extended unemployment benefits are larger for workers who are members of groups that lack funds for a rainy day. Because of labor market discrimination, unequal access to education and training, caregiving obligations, and stagnating wage levels, members of demographic groups, including women, people of color, and less-educated workers, typically lack the private savings held by their counterparts who are members of more advantaged groups.

Indeed, this research finds that during the Great Recession and its aftermath, women, people of color, and low-educated workers improve their job matches when they have access to unemployment benefits even more than their counterparts who are members of wealthier demographic groups. The research team finds that a 53-week increase in UI benefits improves the job-match quality by 0.9 percent for White workers, but improved match quality even more for workers of color: The effect size for workers of color is 1.2 percent.

Similarly, Farooq, Kugler, and Muratori find that workers of color (along with women, less-educated workers, and young workers) see larger returns to increased weeks of benefits when it comes to wage levels. This supports the idea that the improved fit between workers and the jobs they find stems from workers' ability to spend more time searching for a job that is a good match, without sacrificing their basic needs in the short term.

Their findings also suggest that insufficient durations of unemployment benefits during moments of macroeconomic contraction exacerbate inequality in the U.S. labor market. This concern is magnified during today's coronavirus recession because the sectors of the U.S. economy that have been hardest hit are the same ones where women, people of color, and low-educated workers are overrepresented.

There is another reason that policymakers should be deeply concerned about the relationship between job matching and extended unemployment benefits during this crisis in particular. While this research speaks to job match in terms of workers' education levels and wages, we can guess that the extended time provided for job search also allows workers to find jobs that are better matches for them along other dimensions—schedule flexibility, location, and working conditions. During the current public health crisis, working conditions are of outsize importance. The ability to be choosy about the health and safety conditions of one's workplace is more likely to be the difference between life and death for a worker or a member of the worker's family than is typical outside of the context of a public health crisis.

So, what to do about the upcoming expiration of the PEUC program? There is the obvious short-term fix—extend the duration of PEUC benefits so that all workers who are unemployed through no fault of their own can receive unemployment benefits for the amount of time it takes to find a job that is a good match for their skills and their health.

And then, there is the bigger structural issue. It's clear from a macroeconomic perspective that the duration of unemployment benefits should extend automatically during moments of economic contraction. Indeed, a permanent program called the Extended Benefits program is designed to do just this. But the formulae we rely on (known as "triggers") to turn on Extended Benefits are broken, and we are repeatedly left in the situation we find ourselves in today: waiting on political horse trades to enact common sense, economically necessary policy decisions through one-off emergency benefit extensions.

So, to make unemployment compensation work for workers and for the economy as a whole in both the short- and long-term, policymakers should extend PEUC today, but they shouldn't stop there. They should also redesign Unemployment Insurance permanently with improved automatic stabilizers so that payment extensions trigger automatically when economic conditions warrant.

-- via my feedly newsfeed