https://www.lemonde.fr/blog/piketty/2020/10/13/what-to-do-with-covid-debt/

How are States going to deal with the accumulation of public debt generated by the Covid crisis? For many, the answer is clear: central banks will take on their balance sheets a growing share of the debts, and everything will be settled. In reality, things are more complex. Money is part of the solution but will not be enough. Sooner or later, the wealthiest will have to be called upon.

Let's recap. In 2020, money creation has taken on unprecedented proportions. The Federal Reserve's balance sheet jumped from $4159 billion as of February 24 to $7056 billion as of September 28, or nearly $3 trillion in monetary injection in 7 months, which has never been seen before. The balance sheet of the Eurosystem (the network of central banks piloted by the ECB) rose from 4692 billion euros on 28 February to 6705 billion on 2 October, an increase of 2000 billion. In relation to the GDP of the euro zone, the Eurosystem's balance sheet, which had already risen from 10% to 40% of GDP between 2008 and 2018, has just jumped to almost 60% between February and October 2020.

What is all this money used for? In calm weather, central banks are content to make short-term loans to ensure the liquidity of the system. As the inflow and outflow of money in and out of the various private banks never balance exactly to the day, the central banks lend for a few days, amounts which the institutions then repay.

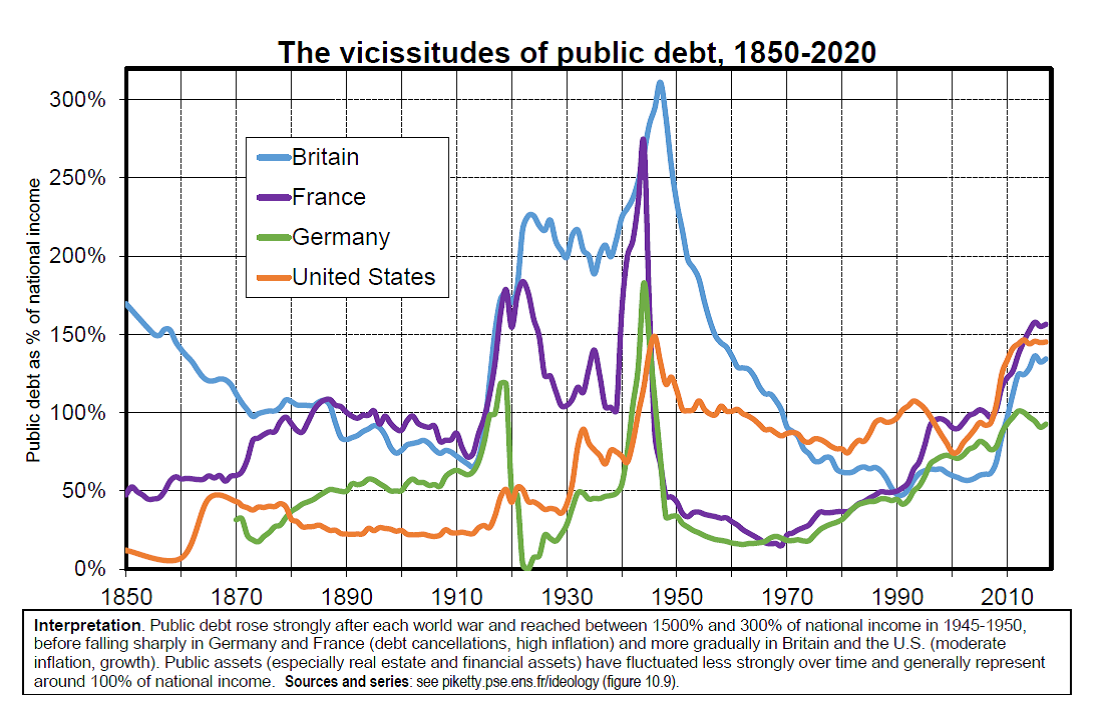

Following the 2008 crisis, central banks started lending money at increasingly longer maturities (a few weeks, then a few months, or even several years) in order to reassure financial players, who were petrified at the idea that their gambling partners would go bankrupt. And there was a lot to be done, because, for lack of adequate regulation, financial gambling has become a gigantic planetary casino over the last few decades. Everyone has started lending and borrowing in unprecedented proportions, with the result that the total private financial assets and liabilities held by banks, companies and households now exceed 1000% of GDP in rich countries (without even including derivative securities), compared to 200% in the 1970s. Real wealth (i.e. the net worth of real estate and businesses) has also increased from 300% to 500% of GDP, but much less strongly, illustrating the financialisation of the economy. In a way, the balance sheets of central banks have only followed (slightly later) the explosion of private balance sheets, in order to preserve their capacity to act in the face of the markets.

The new activism of the central banks has also allowed them to buy back a growing share of public debt securities, while bringing interest rates down to zero. The ECB already held 20% of the public debt of the euro zone at the beginning of 2020, and could hold nearly 30% by the end of the year. A similar development is taking place in the United States.

As it is unlikely that the ECB or the Fed will ever decide to put these securities back on the markets or to demand their repayment, the decision to no longer count them in the total public debt could be taken now. If registration of this guarantee in legal form is desired, which would be preferable, then this might take a little more time and debate.

The most important question is the following: should we continue along this path, and can we envisage that central banks will in future hold 50% and then 100% of public debts, thereby lightening the financial burden on States? From a technical point of view, this would not pose any problem. The difficulty is that by resolving the question of public debt on one hand, this policy creates other difficulties elsewhere, particularly in terms of increasing inequalities of wealth. The orgy of money creation and the purchase of financial securities in fact leads to an increase in stock and property prices, which contributes to the enrichment of the richest. For small savers, zero or negative interest rates are not necessarily good news. But for those who can afford to borrow at low rates and who have the financial, legal and tax expertise to find the right investments, excellent returns are possible. According to Challenges, France's 500 largest fortunes have thus risen from €210 to €730 billion between 2010 and 2020 (from 10% to 30% of GDP). Such a development is socially and politically unsustainable.

It would be different if monetary creation, instead of fuelling the financial bubble, were mobilised to finance a real social and ecological recovery, i.e. by assuming strong job creation and wage increases in hospitals, schools, thermal efficiency and local services. This would alleviate debt while reducing inequalities, investing in sectors useful for the future and shifting inflation from asset prices to wages and goods and services.

However, this would not be a miracle solution either. As soon as inflation becomes substantial again (say 3%-4% per year), we would have to put a stop to money creation and use fiscal means. The whole history of public debt shows this: money alone cannot offer a peaceful solution to a problem of this magnitude, because it leads in one way or another to uncontrolled distributive consequences. It was by resorting to exceptional levies on the better-off that the large public debts of the post-war period were extinguished and that the social and productive pact of the following decades was rebuilt. Let's bet that the same will be true in the future.

Notes on the sources:

On central bank balance sheets, see also this tribune and Capital and ideology (chapter 13)

Balance sheet ECB : 4692 billions € on 28/2/2020, 6705 billions € on 2/10/2020

(39% GDP, 56% GDP)

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/wfs/2020/html/ecb.fst200303.en.html

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/wfs/2020/html/ecb.fst201007.en.html

This is due both to the new asset purchasing programme (PEPP, Pandemic emergency purchase programme) and to the increased used of old ones (in particular PSPP, Public sector purchase programme). See here the decomposition by country (alway with ECB capital keys as target, anchored upon national GDPs): https://www.ecb.europa.eu/mopo/implement/omt/html/index.en.html

GDP 2019 Eurozone (12 000 billions euros) EU 27 (14 000 billions euros) (market prices): https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tec00001/default/table

Balance sheet Fed : 4159 billions $ on 24/2/2020, 7056 billions $ on 28/9/2020

(19% GDP, 33,0% GDP)

https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/bst_recenttrends.htm

BEA US GDP : 21 400 billions $ 2019

-- via my feedly newsfeed