We now have 4.3 million confirmed cases of the novel coronavirus in the United States. The virus moves fast, and policymakers in Washington move slow. Families across the country face a wide array of individual income crises and need federal fiscal support, yet policies to address public health and economic hardship are backsliding. Families, unemployed workers, small business owners, and communities need more money, and only Congress has the means to help.

Congress must deliver a multitrillion-dollar package. One-fifth of families have lost a breadwinner and twice as many have lost income, according to surveys by the University of Michigan and Google. Black, Hispanic, and Asian families, as well as young adults and less educated workers, are being hit much harder than others. This is a clear income crisis, larger than any since the Great Depression.

Early on, when the pandemic first crashed the U.S. economy, policymakers had to act with limited information. Key indicators on public health and the economy were not keeping up with quickly changing conditions. Recessions normally build over months or even quarters. This crisis arrived in days and weeks. In addition, huge disagreements among professional forecasters, including me, and massive uncertainty about the path the coronavirus would take hindered the federal response.

None of those excuses prevail today. Official statistics, administrative data, and new research all have caught up. There is no rapid bounce back in our economy. And there will be no solid economic ground until the coronavirus is under control.

Congress, in those first few months, designed the first relief packages for a crisis they hoped would be over by the summer. They were wrong. It is not over, which means they must do more—even more than in March. Coronavirus cases spiked this month, and the U.S. economy worsened. Deaths from COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus, are consequently on the rise. Policymakers must face this harsh reality. They must go bigger and better. They must move faster.

Workplaces must make it safe enough for workers to return to their jobs. Congress must invest aggressively in public health, testing, contact tracing, and personal protective equipment. They must get money out to make up for lost paychecks and reverse cuts in hours and wages of the employed. Families must have paid health insurance, sick leave, and child care. Renters and homeowners behind on their monthly obligations must get help. As many small businesses as possible must avoid bankruptcy. And Congress must get grants to state and local governments to avoid laying off more teachers and essential workers. Congress must get more money out now.

Do what worked again, and keep it simple

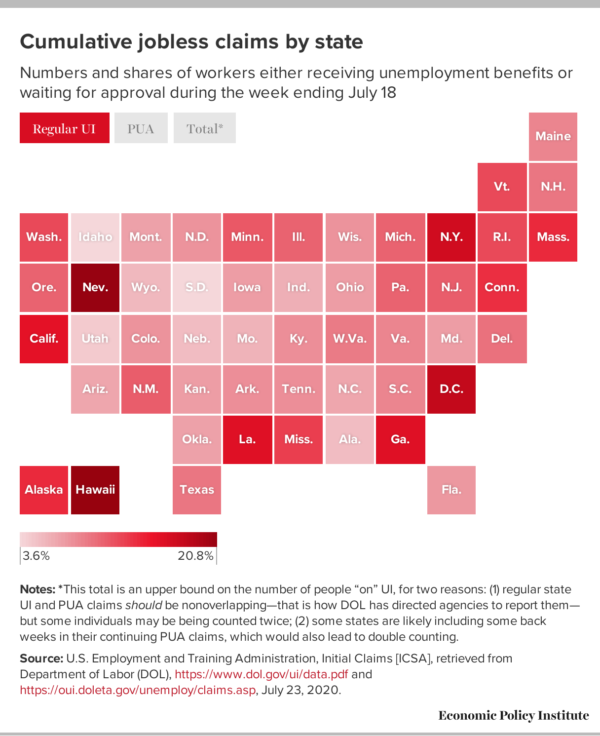

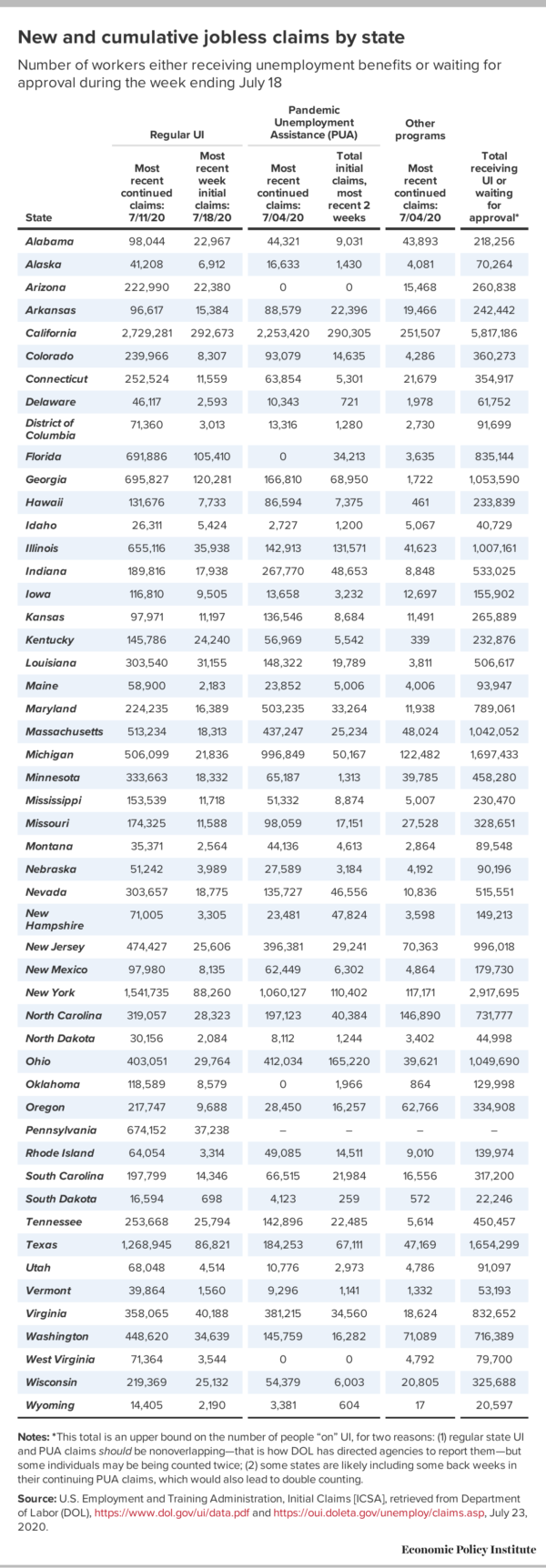

Better jobless benefits are the big success story of the relief provided by Congress so far. In March, Congress made more workers eligible for unemployment benefits, including independent contractors and gig workers, and added an extra $600 per week to those benefits while extending the number of weeks someone could receive benefits. By April, the unemployment rate hit its highest level since the Great Depression, and those enhanced unemployment benefits prevented that joblessness from translating into mass human suffering and a macroeconomic collapse. Currently, around 30 million people are receiving jobless benefits, including those who suffered big cuts in hours or wages. Helping the unemployed is crucial to getting us through this income crisis.

New research by the JP Morgan Chase Institute shows that the better jobless benefits worked. Using bank account data, the researchers find these benefits allowed these families not to pull back on their spending. In fact, their spending in July was somewhat higher than before the start of the coronavirus recession. Keep in mind, lower-income families have been twice as likely as the national average to lose jobs in this crisis. Even before losing their jobs, many could not buy what they needed. One-quarter of families, for example, went without medical care because they could not afford it in 2019. Avoiding medical care now is disastrous.

The extra $600 per week in Pandemic Unemployment Compensation will expire on Friday. The last $600 extra went out last weekend. A lapse in this benefit will mean a delay in payments of weeks. Congress must renew the extra $600 per week now and taper it down only when it is safe to go out and the unemployment rate falls.

Another way to fight the income crisis is one-time payments to all families—referred to as recovery rebates. The first round worked well: Most U.S. families got $1,200 per adult and $500 per child. It came within weeks. Nearly all $300 billion arrived by the end of May. In my forthcoming research with University of Michigan economists Matthew Shapiro and Joel Slemrod, one-fifth of families told us they would mostly spend their rebates, mainly within weeks or a few months. We know from a prior study that families said they will mostly save or pay off debt and will spend some too—the cumulative result of which is for every dollar of rebates, 50 cents was spent quickly.

That's $150 billion—or 4 percent of all consumer spending in the second quarter. These rebates softened the freefall some. And other researchers confirm the sharp upturn in spending when those rebates arrived. The rebates worked. Do it again.

Congress also must extend the enhanced jobless benefits. Again, my forthcoming research shows that half of the unemployed workers in our nation had not yet received any of these benefits by June. Relief packages are pointless if they do not get into the hands of those who need it.

One last piece of the income crisis is employee wage cuts—a hardship not seen since the Great Depression. This income loss comes on top of the layoffs, the lost overtime, and the fewer hours. Many of these workers are employed by small businesses. Congress must get money to small businesses to keep paying employees. Another round of rebates will help, but it cannot make up for less money in every paycheck.

Fix what did not work, and make it simple

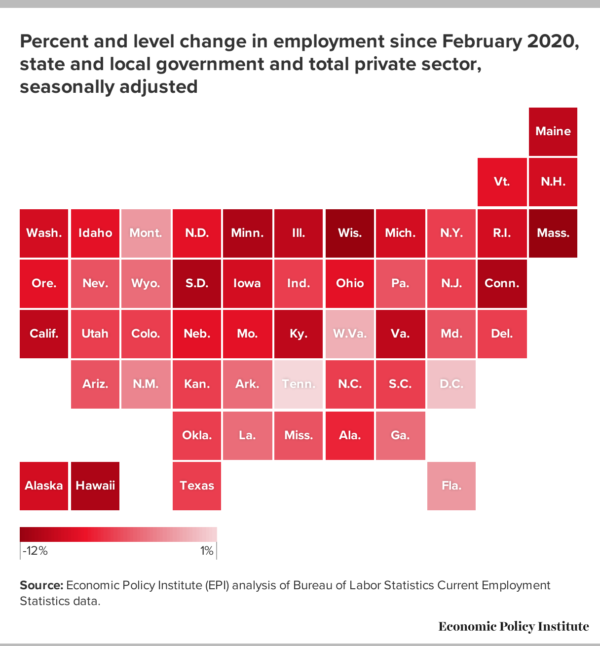

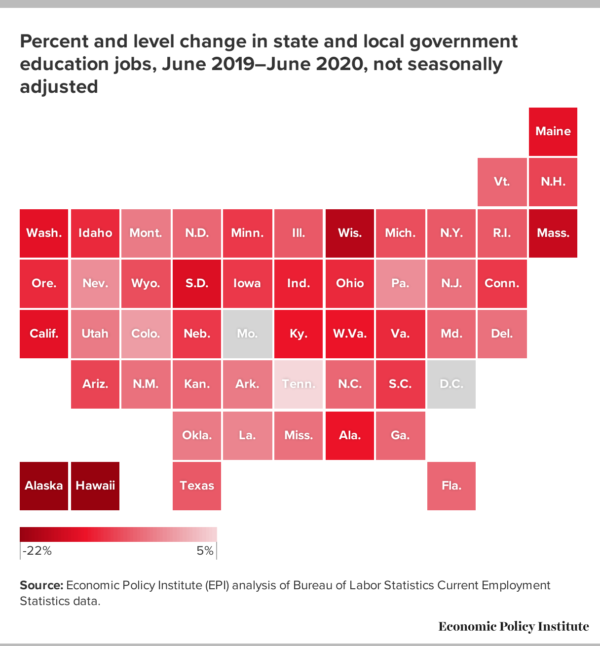

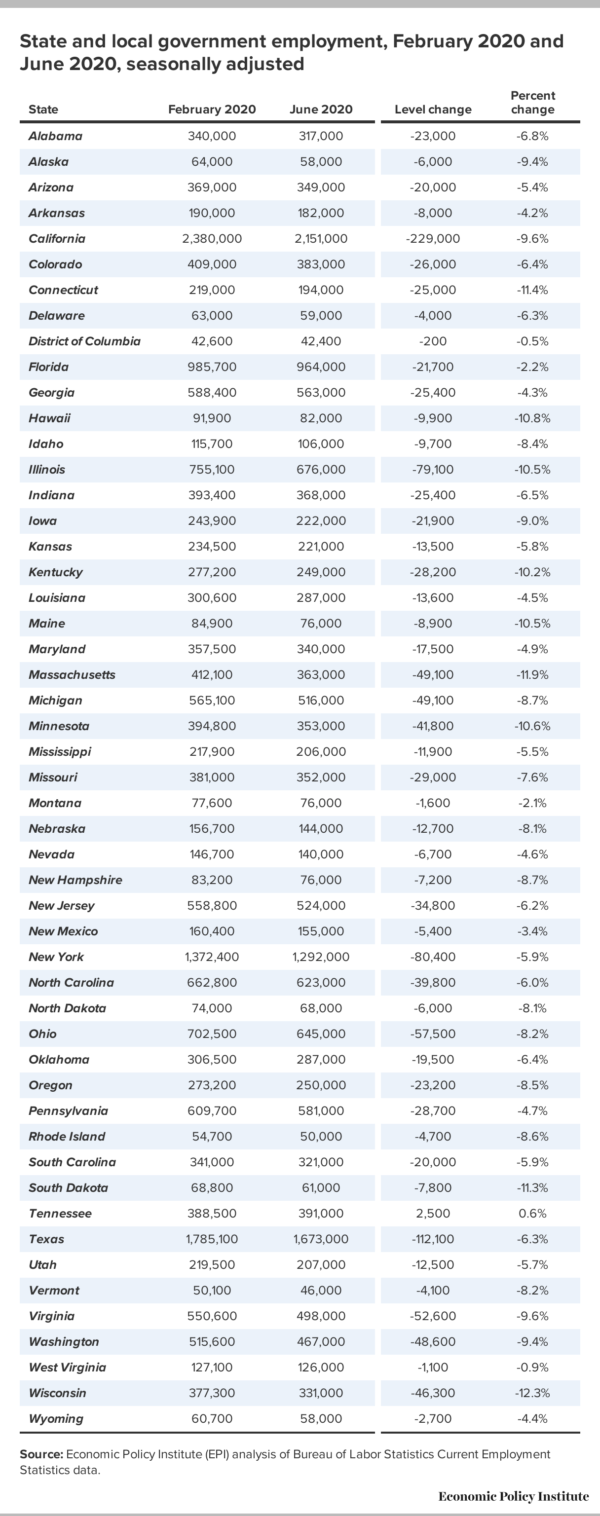

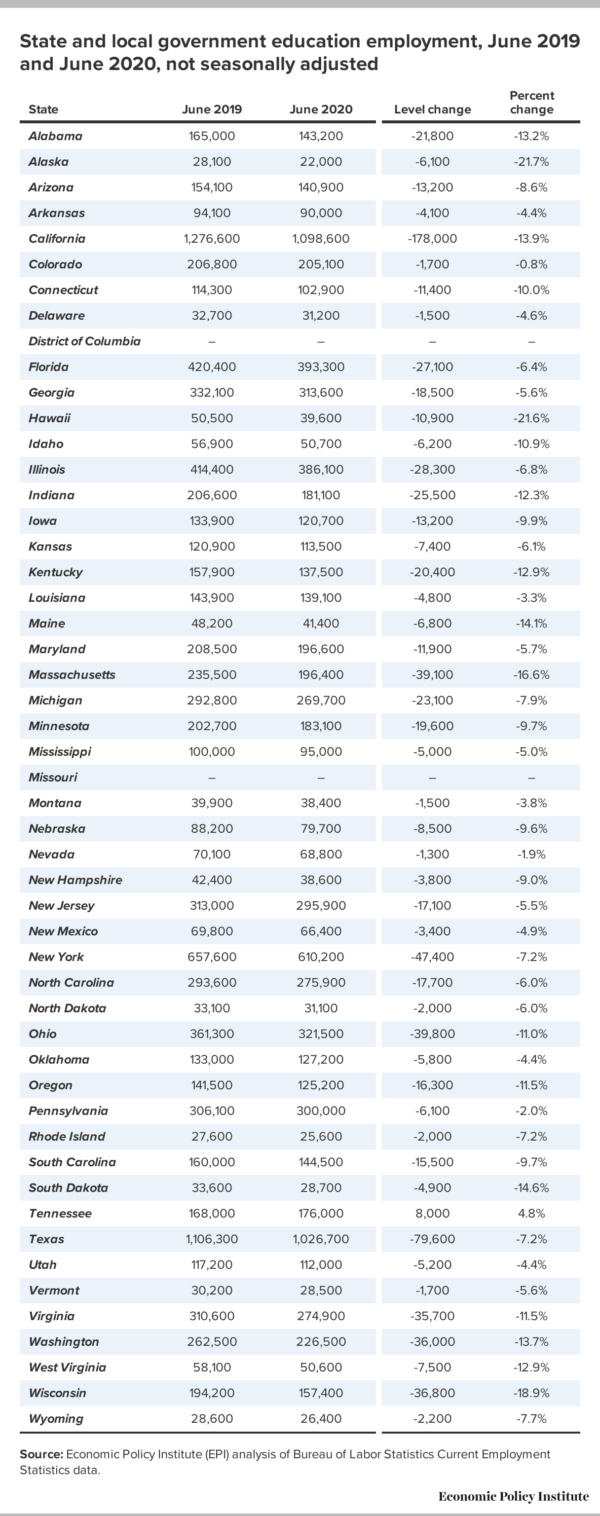

Congress left state and local governments to fend for themselves. It is a disaster. States face rising public health costs from the pandemic at the same time that their revenues have plummeted. As a result, state and local governments had laid off or furloughed 1.5 million workers by June, disproportionately harming women and Black workers. Congress increased its share of Medicaid expenses, but not enough to make up for massive budget shortfalls. State governors are calling on Congress repeatedly to send help. We know from the Great Recession more than a decade ago that our communities need support, or the recovery will be slow and painful. Congress must generously support these fiscally embattled state and local governments.

In the private sector, some businesses have rehired some workers, but that uptick in re-employment is unsustainable amid an unabated public health crisis. Most importantly, Congress must find a better way to get money to small businesses—they are the bedrock of U.S. employment. The Paycheck Protection Program was well-intended but failed to get relief to the hardest hit of these firms. Banks gave loans to their most well-connected customers and those faring relatively well, such as construction businesses that continued operating in the shutdown. But the administration of the loans was confusing and too risky for many businesses. Business owners had to use the funding largely for payroll, but many businesses have other big expenses to overcome to stay afloat.

Then, the rules kept changing. As a sign of the mess, even after Congress put more money into the program, businesses did not borrow. Amanda Fischer, my colleague at Washington Center for Equitable Growth, argues that Congress must do better at targeting smaller businesses. They must expand eligible uses for funding and improve incentives for short-term wage compensation, or work-sharing arrangements. Congress must get relief to business owners of color who are serving low-income neighborhoods and hire workers in those communities who need jobs to come back to and earn living wages.

Finally, Congress cannot rely on the Federal Reserve to prop up Main Street. The Fed stabilized Wall Street this spring, and bond and equity markets soared. But the indirect effects are not enough to help small businesses and Main Street communities. Loans from the Fed, to date, are not widespread enough to save enough businesses and keep municipalities from laying off more teachers and other frontline public servants. Congress must instruct the Federal Reserve to fully use its Main Street and Municipal Lending Facilities, even if it means making some loans that may not be repaid. The Fed has made only a handful of loans so far, even as tremendous need exists for more financial support.

Next relief package from Congress

Congress must do what works and commit to doing whatever it takes to support an economic recovery that is strong, stable, and broadly shared. Congress should spend $6 trillion in its next coronavirus relief package. Specifically:

- $2 trillion to continue enhanced jobless benefits until people are safely back to work

- $1 trillion for grants to state and local governments

- $1 trillion in payments to the hardest-hit small businesses

- $500 billion for public health efforts to contain the pandemic and keep essential workers safe

- $500 billion for another direct payment to all families now and again at the end of the year

- $1 trillion for other efforts to support families in need, such as paid child care and sick leave; and rent and mortgage forgiveness

The cost of doing too little now will be enormous in the coming years. No matter what Congress does next, so many families will never get their loved ones back and will never get the chance to say goodbye. But if Congress acts now and commits to stay the course, our workers will get the dignity of work back, our small business owners will succeed, our essential workers will be kept safe, and our children will have teachers. Congress must fight for our future.

-- via my feedly newsfeed