Last week the Bureau of Labor Statistics officially validated what we already knew: Just a few months into the Covid-19 crisis, America already has a Great Depression level of unemployment. But that's not the same thing as saying that we're in a depression. We won't know whether that's true until we see whether extremely high unemployment lasts for a long time, say a year or more.

Unfortunately, the Trump administration and its allies are doing all they can to make a full-scale depression more likely.

Before I get there, a word about that unemployment report. Notice that I didn't say "the worst unemployment since the Great Depression"; I said "a Great Depression level," a much stronger statement.

To understand why I said that, you need to read the report, not just look at the headline numbers. An unemployment rate of 14.7 percent is pretty horrific, but the bureau included a note indicating that technical difficulties probably caused this number to understate true unemployment by almost five percentage points.

If this is true, we currently have an unemployment rate around 20 percent, which would be worse than all but the worst two years of the Great Depression. The question now is how quickly we can recover.

If we could get the coronavirus under control, recovery could indeed be very rapid. True, recovery from the 2008 financial crisis took a long time, but this had a lot to do with problems that had accumulated during the housing bubble, notably an unprecedented level of household debt. There don't seem to be comparable problems now.

But getting the virus under control doesn't mean "flattening the curve," which, by the way, we did — we managed to slow the spread of Covid-19 enough that our hospitals weren't overwhelmed. It means crushing the curve: getting the number of infected Americans way down, then maintaining a high level of testing to quickly spot new cases, combined with contact tracing so that we can quarantine those who may have been exposed.

To get to that point, however, we would need, first, to maintain a rigorous regime of social distancing for however long it takes to reduce new infections to a low level. And then we would have to protect all Americans with the kind of testing and tracing that is already available to people who work directly for Donald Trump, but almost nobody else.

Crushing the curve isn't easy, but it's very possible. In fact, many other countries, from South Korea to New Zealand to, believe it or not, Greece have already done it.

Bringing the infection rate way down was a lot easier for countries that acted quickly to contain the coronavirus, while the rate was still low, rather than spending many weeks in denial. But even places with severe outbreaks can bring their numbers down if they stay the course. Consider New York City, the original epicenter of the U.S. pandemic, where the numbers of new daily cases and deaths are only a small fraction of what they were a few weeks ago.

But you do have to stay the course. And that's what Trump and company don't want to do.

For a while it seemed as if the Trump administration was, at long last, willing to take Covid-19 seriously. In mid-March the administration introduced social distancing guidelines, although without actually imposing any federal regulations.

But lately all we hear from the White House is that we need to reopen the economy, even though we're nowhere close to where we'd need to be to do so without risking a second wave of infections.

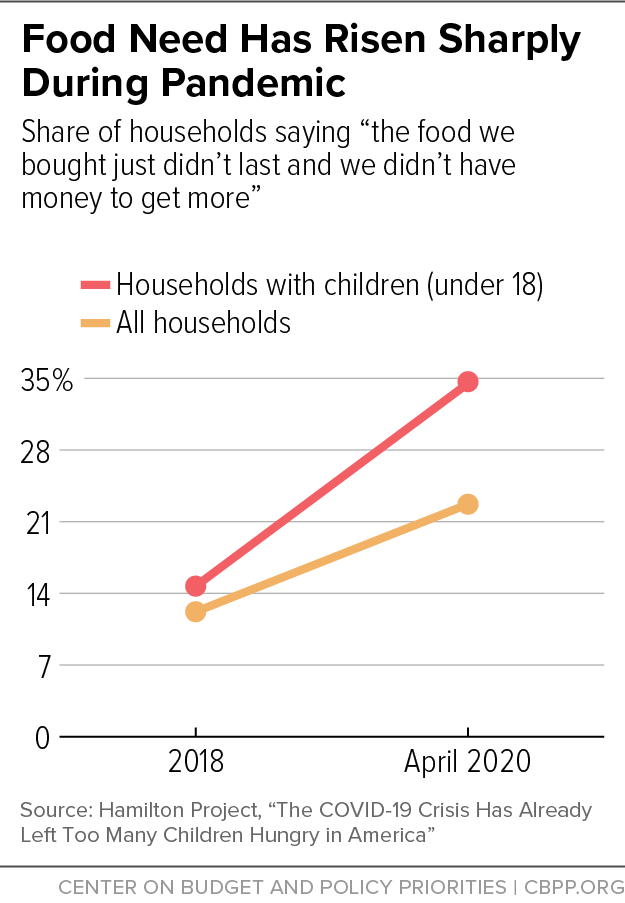

At the same time, the administration and its allies are apparently dead set against providing the financial aid that would let us sustain social distancing without extreme financial hardship. Extend enhanced unemployment benefits, which will expire July 31? "Over our dead bodies," says Senator Lindsey Graham. Aid to state and local governments, which have already laid off a million workers? That, says, Mitch McConnell, would be a "blue-state bailout."

As Andy Slavitt, who ran Medicare and Medicaid under Barack Obama, puts it, Trump is a quitter. Faced with the need to actually do his job and do what it takes to crush the pandemic, he just gave up.

And this retreat from responsibility won't just kill thousands. It might also turn the Covid slump into a depression.

Here's how it would work: Over the next few weeks, many red states abandon social-distancing policies, while many individuals, taking their cues from Trump and Fox News, begin behaving irresponsibly. This leads, briefly, to some rise in employment.

But fairly soon it becomes clear that Covid-19 is spiraling out of control. People retreat back into their homes, whatever Trump and Republican governors may say.

So we're back where we started in economic terms, and in worse shape than ever in epidemiological terms. As a result, the period of double-digit unemployment, which might have lasted only a few months, goes on and on.

In other words, Trump's search for an easy way out, his lack of patience for the hard work of containing a pandemic, may be precisely what turns a severe but temporary slump into a full-blown depression.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We'd like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here's our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.

Paul Krugman has been an Opinion columnist since 2000 and is also a Distinguished Professor at the City University of New York Graduate Center. He won the 2008 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his work on international trade and economic geography. @PaulKrugman

A version of this article appears in print on May 12, 2020, Section A, Page 26 of the New York edition with the headline: How to Create a Pandemic Depression. Order Reprints | Today's Paper | Subscribe

-- via my feedly newsfeed