https://equitablegrowth.org/weekend-reading-how-minority-communities-are-disproportionately-affected-by-the-coronavirus-and-its-recession-edition/

his is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we're highlighting from elsewhere. We won't be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

Two congressional reports released this week confirm what the media has already been reporting: Communities of color, and especially African Americans, are disproportionately being exposed to the coronavirus, dying from the disease it causes, COVID-19, and losing their livelihoods amid the recession that the pandemic caused. The two reports also make clear that entrenched economic and racial inequalities in our society are behind these disparities. Liz Hipple looks at the effects on communities of color of in terms of occupational segregation, which disproportionately leads minorities into lower-wage jobs; residential segregation, which disproportionately forces minorities to live in overcrowded and poor conditions; and disproportionately high rates among black Americans of pre-existing health conditions, which increase the chances of fatal complications from COVID-19. Hipple explains how these inequalities put minorities at a disproportionate disadvantage during the coronavirus health and economic crises, and shows why solutions to these underlying issues will be key to preventing racial gaps from widening further.

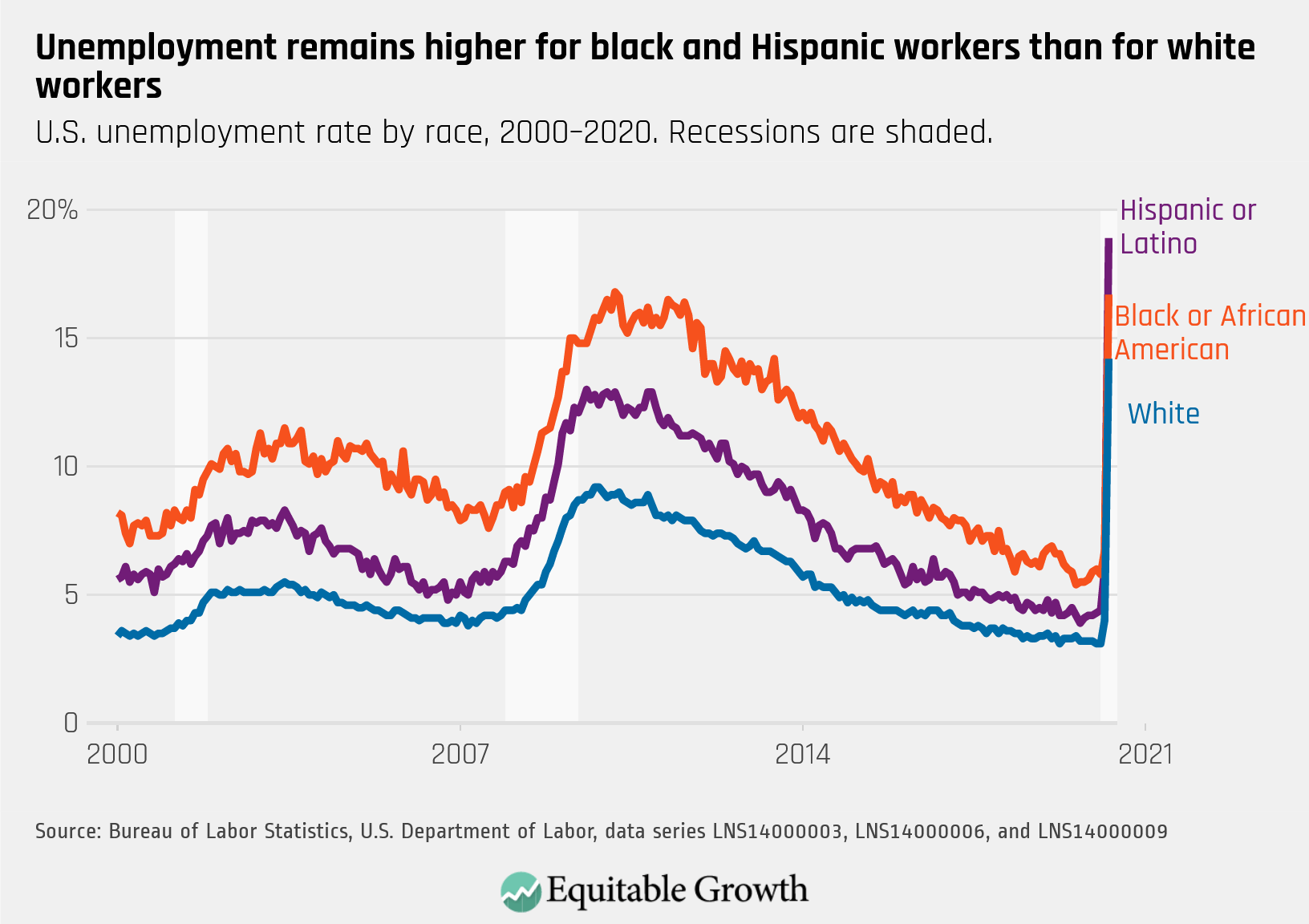

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics released employment data for the month of April today, showing the highest unemployment rate since the Great Depression: 14.7 percent. While workers across the economy are feeling the effects of the coronavirus recession, Heather Boushey and Carmen Sanchez Cumming write that workers of color, workers in low-wage industries, and less educated workers, and women are being hit particularly hard. Boushey and Sanchez Cumming analyze the newly released data and trends arising from the economic downturn, concluding with several ideas policymakers can enact in order to support the most vulnerable workers and ensure the economic recovery will be swift.

One of the sectors most severely hit by shelter-in-place orders and other quarantine and social distancing measures is the U.S. restaurant industry, which was one of the fastest-growing areas of the U.S. economy prior to the pandemic. Estimates from the National Restaurant Association say that around two-thirds of the sector's almost 12 million-person workforce has been laid off as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. And while the CARES Act and subsequent refunding of the Paycheck Protection Program provided hundreds of billions of dollars for small businesses—of which the restaurant industry is mostly comprised—food-service borrowers received only the fifth-highest amount of stimulus money. T. William Lester explains the underlying inequalities and structures existed within the industry before the pandemic and why this funding was not nearly sufficient to help restaurants weather the coronavirus recession. Lester then offers three proposals that policymakers can take up to bolster the restaurant industry specifically, as this sector will be incredibly important for a swift and sustainable economic recovery.

How has the pandemic affected global trade, specifically trade in medical equipment and supplies, and pharmaceuticals? Kimberly A. Clausing makes the case for preparation rather than isolationism to solve the trade challenges surrounding the global pandemic. Considering that the United States depends heavily on global medical supply chains—we both import and export large quantities of medical equipment, supplies, and pharmaceuticals—cutting off trade is not a viable policy option. Clausing disproves three fallacies that have arisen in the face of the pandemic about international trade, self-sufficiency, globalization, and immigration, and highlights three important lessons we can learn from this crisis.

This week, a group of 12 of the most highly regarded antitrust minds in the country submitted comments to the House Judiciary Committee on the state of U.S. antitrust laws and enforcement. The signatories included Michael Kades, Equitable Growth director of markets and competition policy, who wrote that the group's conclusions about digital market concentration were blunt and its prognosis bleak. Kades shared a detailed explanation of what's wrong with antitrust law as it currently stands, as well as four policy recommendations to Congress that can better protect competition, particularly in digital markets.

Links from around the web

New polling shows that Hispanic workers are almost twice as likely as their white counterparts to have lost their jobs amid the coronavirus recession. Black workers are also more likely to have lost their jobs, though the disparities between black and white workers is smaller than that of Hispanic and white workers. In The Washington Post this week, Tracy Jan and Scott Clement review the results of the poll, which was done prior to today's release of unemployment data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The poll also showed that while half of those interviewed who had lost their jobs had applied for Unemployment Insurance benefits, only 28 percent had received UI benefits.

In addition to racial disparities in job losses from the coronavirus pandemic, minority-owned businesses have also been largely deprived of access to federal stimulus funds provided in the CARES Act and subsequent small business funding. Marcus Baram reports for FastCompany that some surveys show at least 90 percent of businesses owned by people of color either have been or will be shut out of the Paycheck Protection Program. This could be attributed to minority communities tending to rely on smaller community banks and credit unions, which had access to less of the stimulus funding than their larger banking counterparts, and because communities of color tend to be underbanked to begin with. Though the second round of PPP funding set aside $60 billion for small banks and community lenders, Baram writes, the program is still not effective in getting badly needed funds to minority-owned banks to disburse among minority-owned businesses.

This disproportionate economic toll on communities of color is not unique to the coronavirus recession. During the Great Depression and the Great Recession, black unemployment was higher than national unemployment rates, and, writes Aaron Ross Coleman for Vox, who says "over the past 30 years, you can't find a recession that hasn't been more severe for black workers than for whites." The wealth gap between black and white families compounds this crisis because black households have less of a financial cushion to fall back on and because the coronavirus recession is particularly damaging to wealth-creating black entrepreneurship, which was already in a precarious position before the downturn began. Economic recovery also takes much longer for communities of color than for their white counterparts, and, Coleman explains, black Americans were not able to fully recover from the Great Recession before the coronavirus recession hit. These and other factors together mean that black communities will not only experience the economic and public health crises more sharply now, but also that, without needed policy reforms, the negative effects will continue much longer into black Americans' future.

Modern disaster relief, from Hurricane Katrina to the coronavirus pandemic, has utterly failed black communities across the United States, writes Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw for The New Republic. And while the pandemic is impacting all races and ethnicities, it is impossible to ignore the disproportionate effects on communities of color and the structural disparities that put them at an extreme disadvantage compared to white communities. Enacting a colorblind response to coronavirus pandemic would be misguided, Crenshaw opines, because ignoring the structures that disproportionately put communities of color in harm's way will only ensure they are further harmed in the next crisis. Crenshaw looks at how past actions to combat previous crises have done just that, from the New Deal to the GI Bill, and how each one has weakened communities of color and their ability to recover fully from the next crisis.

Friday figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth's "Coronavirus recession deepens U.S. job losses in April especially among low-wage and less-educated workers and women" by Heather Boushey and Carmen Sanchez Cumming.

The post Weekend reading: How minority communities are disproportionately affected by the coronavirus and its recession editionappeared first on Equitable Growth.

-- via my feedly newsfeed