https://www.bradford-delong.com/2020/03/the-federal-reserve-appears-to-be-not-just-the-first-but-the-only-instrumentality-of-the-federal-government-to-actually-do-so.html

-- via my feedly newsfeed

AFL-CIO

AFL-CIOOn the latest episode of "State of the Unions," podcast co-hosts Julie Greene Collier and Tim Schlittner talk with M.K. Fletcher, AFL-CIO Safety & Health specialist, about all things COVID-19, what the labor movement is doing and how we are responding to ensure that front-line workers' needs are taken care of.

Listen to our previous episodes:

Talking with AFL-CIO Executive Vice President Tefere Gebre(UFCW) about his journey from being an Ethiopian refugee to success in the labor movement in Orange County, California, and in Washington, D.C., and the people and institutions that helped him along the way.

A conversation with the Rev. Leah Daughtry, CEO of "On These Things," about Reconnecting McDowell, an AFT project that takes a holistic approach to revitalizing the education and community of McDowell, West Virginia, and how her faith informs her activism.

Talking to Fire Fighters (IAFF) General President Harold Schaitberger about the union's behavioral health treatment center dedicated to treating IAFF members struggling with addiction and other related behavioral challenges. The discussion also addresses the toll of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on firefighters and their families, the response of the IAFF in its wake, and the life of a firefighter.

A chat with the podcast team on their favorite episodes of 2019.

A discussion with Cas Mudde, a political scientist at the University of Georgia, on the resurgence of right-wing politicians and activists across the world, much of it cloaked in populist, worker-friendly rhetoric.

Talking with Guy Ryder, the director-general of the International Labor Organization, about the international labor movement, the idea of "decent labor" and the future of work.

"State of the Unions" is available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher and anywhere else you can find podcasts.

In yet another upside surprise to the U.S. labor market, payrolls grew strongly last month, up 273,000, well above expectations. Upward revisions to earlier months show that contrary to what many have expected, the monthly pace of job gains has accelerated in recent months. The unemployment rate held steady at 3.5 percent, but wage growth, which has been remarkably unresponsive to strong labor demand, remains a soft spot, stuck at 3 percent, year-over-year, just slightly ahead of consumer inflation which is running at around 2.5 percent.

Calm before the storm

As our smoother shows, averaging monthly payroll gains over various time spans, over the past 3 months, payrolls are up 243,000 per month. Over the past year, they're up less than that: 201,000. Given that most labor market analysts expected employment gains to slow as we closed in on full capacity in the job market, this acceleration is quite remarkable.

However, there are two counterpoints to this positive development. First, wage growth is also remarkable, but not in a good way: at 3 percent over the past year, it's surprisingly soft given these job gains and persistently low unemployment rate. Second, as regards the impact of the coronavirus on today's numbers, it's important to recognize that jobs reports are coincident, if not lagging, indicators. As of today, clear disruptions to both the global and US economy are growing increasingly clear in the data, from sharply reduced airline traffic, to supply chain disruptions, to falling consumer confidence. Forecasts are even more uncertain than usual in this climate–we still don't know how many people and places will be hit by quarantines, closed workplaces and schools, or even by Covid-19, the illness caused by the virus.

But that said, my guess is that GDP growth sharply decelerates in at least the first half of this year. In that regard, I view this jobs report as the calm before the storm. There was a slight bump up in involuntary part-timers last month, which could be a harbinger of what's to come, as labor demand gets hit by virus-induced decreased consumer demand, but it is a distinct possibility that in a few months, we'll longingly look back on this report.

What's not up with wage growth?!?

Both figures–the first for all private-sector workers, the second for middle-wage workers–show a deceleration in trend wage growth. How does that square with such a strong job market on the jobs side? One explanation is that this particularly series is weaker than others, but in fact, most series roughly agree that wage growth is, if not slowing down, not speeding up. Another is that workers just don't have the bargaining clout needed to press for the types of gains we'd expect in such tight conditions. This is surely part of the explanation, though it's tricky then to puzzle out why wages were growing at a good clip a relatively short while back.

Not at full employment

Another explanation, one consistent with econ 101, is that increased labor supply is meeting strong labor demand. The surfeit of available jobs is pulling new workers in off the sidelines and allowing incumbent workers to increase their hours. Some indicators, especially the fact that employment rates have increased over the past year, suggest there's something to this explanation. The critical implication is that there's still "room-to-run" in the U.S. job market. It is not at full employment.

This next figure underscores that case using price data, both the price of goods and labor (i.e., wage growth). The unemployment rate has been below the Fed's estimate of the lowest rate consistent with stable inflation–their so-called "natural rate"–for about two years! But not only has inflation consistently missed the Fed's 2 percent target from the downside; we now observe wage deceleration. Based on these relationships, I simply do not think there's a coherent argument that the U.S. labor market is at full capacity.

One of the problems with even the best journalism is that it reports day-to-day events without putting them into context, thereby telling us about the weather but not the climate. So it is with the news that ten-year Treasury yields have hit a record low.

Although the latest move is due to increased risk aversion triggered by the coronavirus this merely continues a long-term trend. Nominal yieldshave been trending down since the 80s, and real yields probably since it 90s.

Why? Standard explanations talk of the shortage of safe assets and global savings glut. Useful as they are, such explanations miss something important. This is that basic theory (and common sense) tells us that there should be a link between yields on financial assets and those on real ones, so low yields on bonds should be a sign of low yields on physical capital.

And they are. My chart shows that the profit rate for US non-financial companies has trended down since the 1950s. I'm not using fancy Marxian calculations here – though they tell a similar story. I'm simply using the Fed's own numbers, expressing pre-tax profits as a percentage of non-financial assets measured at historic cost. Although this profit rate is higher than it was in the crises of 2000-01 and 2008-09, it is much lower now than it was in the 60s and 70s. And profits have never sustainably recovered from the crisis of the 70s and 80s. Even by their own lights, therefore, neoliberal policies – such as lower taxes, sharper CEO incentives, weak unions and a focus on shareholder value - have failed.

You might find this surprising. How can we reconcile it with the fact that, until a few days ago, the stock market was at a record high? Simple. For one thing, listed firms are an unrepresentative sample of all firms. They tend to be bigger and more monopolistic than the average – and the bigger ones among them are more profitable. And for another, the market's high valuations reflect the hope that firms which are not very profitable (or loss-making such as Tesla) today will deliver monopoly profits in future. If we look past a few giant monopolies, the typical American firm has been struggling.

In light of this, three Big Facts make sense.

The first is the slowdown in productivity growth. Having risen by 2.2% per year in the 50 years to 2007, output per worker-hour has grown only one per cent per year in the last ten years. One reason for this (of several) is that lower profits reduce the incentive to invest and innovate. This is especially the case when low profits for many firms co-exist alongside monopoly power for a few, because monopolies prefer to entrench their power rather than innovate. Secular stagnation did not drop from the sky. It's the product of trends within capitalism.

The second is capitalism's vulnerability to crisis. To see this, imagine a different world in which there were abundant big profit opportunities for non-financial firms in the early 00s. The flow of savings from Asia would then have financed these cheaply. We'd thus have seen strong growth in the real capital stock and in productivity and profits (and maybe wages and employment too). But we didn't, because there were few such opportunities. Savings flowed instead into housing and mortgage derivatives thereby stoking up a bubble which led to the crisis.

The third fact is documented by Anne Case and Angus Deaton in their new book, Deaths of Despair, wherein they show that, for middle-aged white people without much education, deaths from suicide, alcohol and drug misuse have soared since the 90s. A big reason for this is that employment opportunities for such people have worsened; even in today's supposedly "tight" labour market, people without degrees are much less likely to be in work than they were in the 90s. And many of those who are in work are in worse jobs. Case and Deaton note that white men without a degree earn less in real terms than they did in 1979. Fewer and worse jobs mean a lower sense of self-worth, stress, family breakdown and hence deaths of despair.

But why have such job opportunities declined? It's easy to blame globalization or technical change. But these are different ways of saying that it is no longer profitable for capitalism to employ less-skilled people at a decent wage.

The drop in bond yields is therefore one of the more innocuous symptoms of a dysfunctional capitalism.

Of course, all these trends have long been discussed by Marxists: a falling rate of profit (pdf); monopoly leading to stagnation; proneness to crisis; and worse living conditions for many people. And there is plenty of evidence (pdf) for them. The problem is, however, that many people want to shut their eyes to this evidence. In this sense, perhaps today's two big stories – the record-low for bond yields and the success of Joe Biden in the Super Tuesday primaries – are related.

While the Fed acted preemptively Tuesday, it is still too early to say much that is definitive about the economic threat from coronavirus. We do know, however, that this is one of the most dangerous and disruptive disease outbreaks since World War I.

Science and medicine have of course progressed massively since the 1918 Spanish flu. On the other hand, the world has nearly five times as many people now, and our interconnection is vastly greater, with 2.8 million people flying each day, in the United States alone, inside metal tubes with recirculating atmospheres. Large fractions of the world population live in places with little ability to carry out systematic health policies.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, roughly one-third of the world's population was infected with the deadly Spanish flu, and 50 million people died — about 3 percent of global population then and a mortality rate of about 1 in 10. Suppose with novel coronavirus the mortality rate turns out to be 1 percent and the disease reaches 10 percent of the world, so that fatalities amount to not 1 percent but 0.1 percent of the global population. The result would be more than 7 million deaths.

What we have seen so far has already had far-reaching economic effects. International meetings are being canceled. Shipments from Asia to the Port of Los Angeles are likely to be down by 25 percent in February. Financial markets, which are forward-looking, lost $6 trillion over six days before regaining some of the lost ground. It is close to an even chance the U.S. and global economies will go into recession in the next 18 months.

The questions in the current moment properly revolve first and foremost around public-health strategy. But there is much for economic policymakers to consider as well. Unfortunately, the tool that has received the most attention — monetary policy — is not likely to be very effective in a crisis of this kind, and the way it's used could create problems down the road. It may on balance be desirable to cut interest rates — as the Fed voted to do Tuesday ― but the principal focus should be elsewhere.

Common sense offers the most important point. When, as in the 2008 financial crisis, output is dropping because consumers and businesses cannot afford to repay loans or get new ones, lowering interest rates and making more credit available is the natural and appropriate policy response. But when GDP falls because businesses cannot get components necessary to generate output, because quarantines limit people's ability to work and because potential customers are rationally afraid to enter public spaces, then monetary policy is much less useful.

Moreover, this is all happening when the efficacy of monetary policy may already be largely exhausted. With 10-year U.S. rates approaching 1 percent, high uncertainty and limited room for cutting short-term rates, it is far from clear how much monetary moves can encourage economic activity, even without a pandemic.

There are also tactical issues to consider. The hardest moments for economic policymakers are when the power of the tool at their disposal is less than what is generally supposed. In such a circumstance, policy can function better as a potentially potent "sword of Damocles" than it would if its limited efficacy were laid bare. Closely related to this is the idea of never shooting your last bullet. And to the almost inevitable extent that it would appear political, a sharp move to easy money may undercut the Fed's credibility.

Despite all this, Tuesday's rate cut may nonetheless have been the right option, simply to avoid adding disappointment with the central bank to the current challenges. But the benefits of monetary pyrotechnics like Tuesday's in the form of extraordinary timing and size of monetary moves have to be balanced against the alarm they may cause and the way they leave central banks exposed as lacking effective tools.

Much more attention should be devoted to economic policies better targeted at pandemic risk.

First, central banks should develop a facility to assure that credit is not cut off to key sectors of the economy, come what may. Steadily available credit is much more important than lower-priced credit.

Second, as huge excess capacity at major global ports suggests, this is a moment for less — not more — interference with trade flows. Though it may go against the president's instincts, the United States should lead a global effort to reduce tariffs as a source of stimulus for the duration of the health emergency.

Third, planning should begin for fiscal expansion via federal budgetary investments in areas like the purchase of ventilators, videoconferencing equipment and distance-education technologies, all of which are directly connected to the coronavirus problem. And, of course, there is far more risk of spending too little on health research and production of health goods than in spending too much.

Fourth, international financial institutions' failure to move to help the world's poorest countries at a moment when they could suffer an AIDS-level catastrophe is scandalous. The United States should use its influence to assure that the International Monetary Fund, World Bank and regional banks step up on behalf of all nations, for all nations.

Just as the 2008 financial crisis upended the 2008 presidential election, coronavirus may upend this presidential campaign. 2008 was about money and the economy. This will be about money and life and death.

Social network analysis is a branch of data science that allows the investigation of how people connect and interact. It can help to reveal patterns in voting preferences, aid the understanding of how ideas spread, and even help to model the spread of diseases. It can also be used to find out who is at the centre of the movie universe.

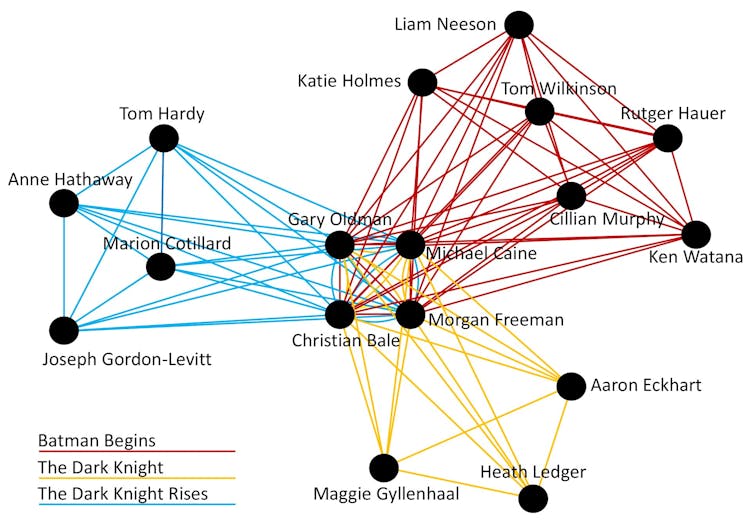

To give an example, the picture below shows the social network of actors appearing in Christopher Nolan's three Batman movies. Each node in this network corresponds to an individual actor. Connections between actors indicate an appearance in a movie together and different coloured connections represent different movies. The network clearly shows that Christian Bale is very central, having appeared in all three movies and with all other actors. The same is also true of Gary Oldman, Michael Caine and Morgan Freeman. In contrast, the remaining actors are rather peripheral and have fewer connections to others.

The same principles can be used to generate a social network of all actors from all movies. Luckily, the information is available through IMDB, which contains cast lists of around 160,000 different movies. This leads to a large social network of around 400,000 actors and nearly 10 million different connections. From here it is possible to determine the most "important" or "central" actors in this network .

One way of measuring importance is to simply count the number of movies that an actor has appeared in.

The top spots are occupied by actors from Indian cinema – with the great Bollywood actress Sukumari winning the competition, having made 703 credited movie appearances. The next actors are then [Jagathy Sreekumar], Adoor Bhasi, Brahmanandam, Manorama, Sankaradi and Prem Nazir, who each appear in more than 500 movies. The only non-Bollywood actor breaking the top 20 is Oliver Hardy, who has 373 films to his name. Then, if your were to look for any of this year's acting Oscar winners, you would have to go all the way down to the bottom to find Brad Pitt, who has made a total of 56 movie appearances.

Another simple statistic from this network is the number of different people that each actor has appeared with. In this case, the top ranked actors again come from the world of Bollywood, with actors such as Nassar, Sukumari and Manorama all having appeared with more than 2,500 people. Other prominent names include Christopher Lee and John Carradine at just over 2,000, and John Wayne on 1,900. In comparison, the highest of this year's Oscar winners is again Brad Pitt on a lowly 735, while Renée Zellweger and Joaquin Phoenix both have disappointing statistics of less than 500.

A trait of the above two measures is that they highlight actors that happen to have appeared in many movies that also feature large casts. Other methods of finding central actors are therefore also needed. One such measure is "betweenness centrality", which considers the number of shortest paths in a network that pass through a particular node. This helps to detect the "middlemen" that serve as a links between different parts of a network. A useful analogy can be drawn with road networks of cities. Short driving routes across a city will often pass through the same locations in the road network. As a result, the nodes at these locations are considered more "central" and important to the network.

In social networks we can do similar things by looking at the shortest paths between actors and then identifying actors that always seem to appear on these paths. According to these measures, the top five most central actors are now Christopher Lee, Michael Caine, Harvey Keitel, Christopher Plummer and Robert De Niro. By comparison, none of this year's recipients of acting Oscars appears in the top 1,000 of this list.

It is noticeable that the top actors in these lists have all had very long acting careers. Their being middlemen then is natural since long careers bring about more acting opportunities, helping to improve an actor's network connectivity. So how do today's Oscar winners compare? Right now it seems that they have some way to go. But we really should be fair and give them a few more decades before making a final judgement.

![]()

Rhyd Lewis, Reader in Mathematics, Cardiff University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Photo by sergio souza from Pexels

A survey of West Virginia GDP by industrial sectors for 2022, with commentary This is content on the main page.