This column is adapted from a chapter in "Meeting Globalization's Challenges" (Princeton University Press), a collection of papers by scholars who contributed to a conference at the International Monetary Fund on Oct. 11, 2017. The book will be published on Nov. 4.

Concerns about adverse effects from globalization aren't new. As U.S. income inequality began rising in the 1980s, many commentators were quick to link this new phenomenon to another new phenomenon: the rise of manufactured exports from newly industrializing economies.

Economists took these concerns seriously. Standard models of international trade say that trade can have large effects on income distribution: A famous 1941 paper showed how trading with a labor-abundant economy can reduce wages, even if national income grows.

And so during the 1990s, a number of economists, myself included, tried to figure out how much the changing trade landscape was contributing to rising inequality. They generally concluded that the effect was relatively modest and not the central factor in the widening income gap. So academic interest in the possible adverse effects of trade, while it never went away, waned.

In the past few years, however, worries about globalization have shot back to the top of the agenda, partly due to new research and partly due to the political shocks of Brexit and U.S. President Donald Trump. And as one of the people who helped shape the 1990s consensus — that the contribution of rising trade to rising inequality was real but modest — it seems appropriate for me to ask now what we missed.

The 1990s Consensus

There was confusion and debate during the mid-1990s over how to use data on trade to assess wage impacts. Most studies focused on the volume of trade and the amount of labor and other resources embedded in imports and exports. Some economists objected to this approach, preferring to focus on prices rather than quantities.

What eventually emerged was a "but for" approach: asking how different wages would have been but for the rise of manufactured exports from developing countries — increases that were minimal in 1970 but higher by the mid-1990s. It turned out that imports of manufactured goods from developing countries, while much larger than in the past, were still small relative to the size of advanced economies — around 2% of their gross domestic products. This wasn't enough to cause more than a modest change in relative wages. The effect wasn't trivial, but it wasn't big enough to be a central economic story, either.

Hyperglobalization

These assessments of the impact of trade made around 1995, inevitably relying on data from a couple of years earlier, were probably correct in finding modest effects. In retrospect, however, trade flows in the early 1990s were just the start of something much bigger, or what a 2013 paper by economists Arvind Subramanian and Martin Kessler called hyperglobalization.

Until the 1980s, it was arguable that the growth of world trade since World War II had mainly reflected a dismantling of the trade barriers erected before the war; world trade as a share of world GDP was only slightly higher than it had been in 1913. Over the next two decades, however, both the volume and nature of trade moved into uncharted territory.

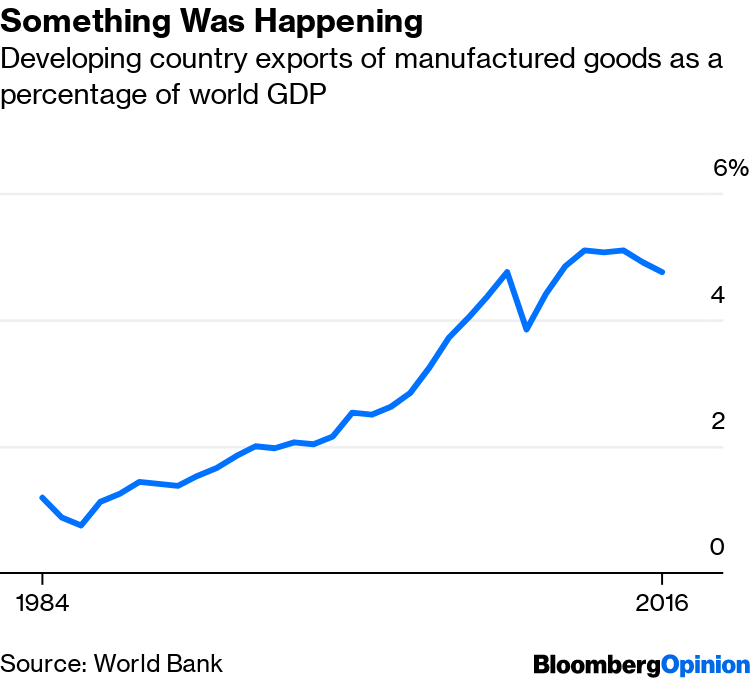

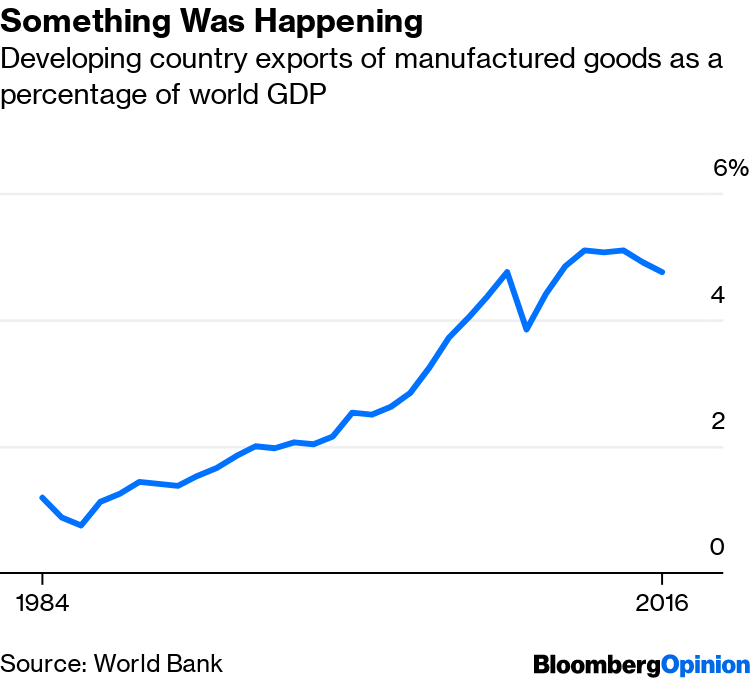

This chart shows one indicator of this change: manufactured exports from developing countries, measured as a share of world GDP. What seemed in the early 1990s like a major disturbance in the trade force was just the beginning.

What caused this huge surge in what was, in the 1990s, still a fairly novel form of trade? The answer probably includes a combination of technology and policy. Freight containerization was not exactly new, but it took time for businesses to realize how the reduction in transshipping costs made it possible to move labor-intensive parts of the production process overseas. Meanwhile, China made a dramatic shift from central planning to a market economy focused on exports.

Since manufactured exports from developing countries, measured as a share of the world economy, are now triple what they were in the mid-1990s, should we conclude that the effect on income distribution has also tripled? Probably not, for at least two reasons.

First, a significant part of the increase in developing-country exports reflects the rapid growth of trade among the modernizing economies of Asia, Africa and Latin America. That's an important story, but it's not relevant to the impact on advanced-country workers. Even more important, though, the nature of this trade growth — involving goods made by both unskilled and highly skilled workers — means that the value of the labor involved in North-South trade hasn't risen nearly as fast as the volume.

Consider two cases: imports of apparel from Bangladesh and imports of iPhones from China. In the first instance, we are in effect importing the services of less educated workers, putting downward pressure on the demand for such workers in the U.S. In the second case, though, most of the value of the iPhone reflects work done in high-wage, high-education countries like Japan; we are in effect importing skilled as well as unskilled labor, so the impact on income distribution should be much smaller.

Despite these qualifications, it's clear that the impact of developing-country exports grew much more between 1995 and 2010 than the 1990s consensus imagined possible, which may be one reason concerns about globalization made a comeback.

Trade Imbalances

One contrast between the way scholars measure globalization's impact and the way the broader public looks at it — the approach taken by Trump, for example — is the focus on trade imbalances. The public tends to see trade surpluses or deficits as determining winners and losers. But the economic trade models that underlay the 1990s consensus gave no role to trade imbalances at all.

The economists' approach is almost certainly right for the long run, both because countries must pay their way eventually, and because trade imbalances mainly affect the relative shares of traded and nontraded sectors in employment, with no clear effect on the overall demand for labor. Yet rapid changes in trade balances can cause serious problems of adjustment — a broader theme that I'll return to shortly.

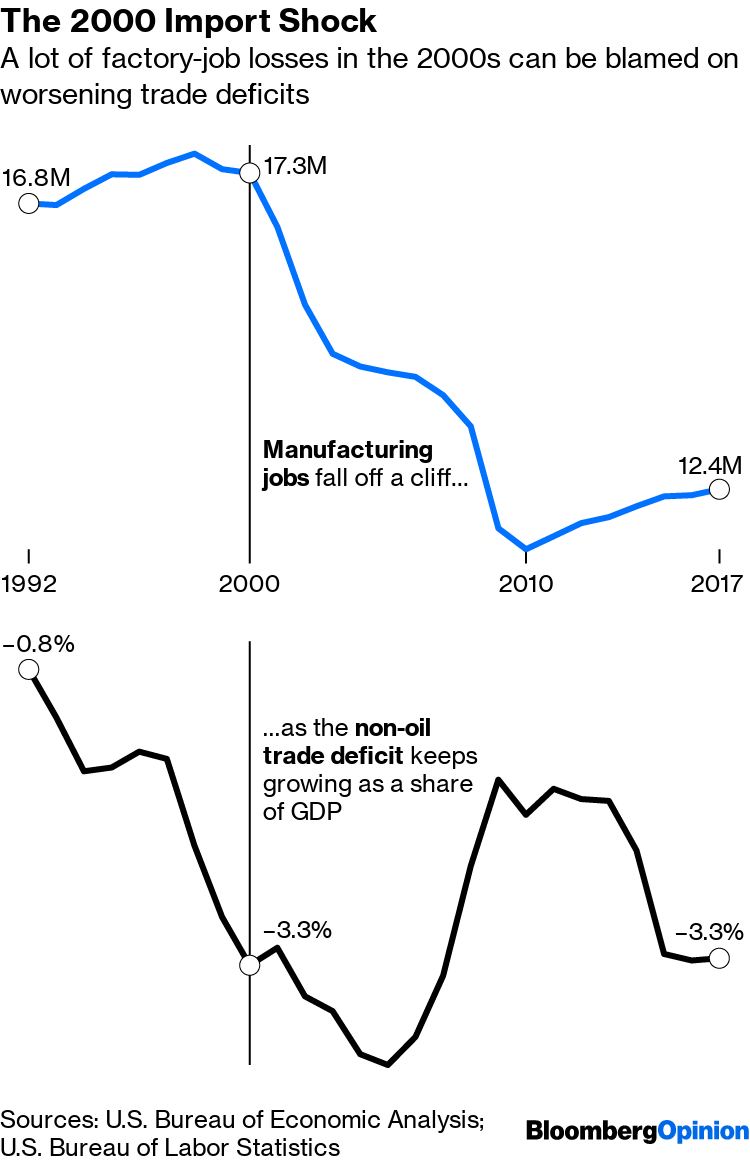

Consider, in particular, the comparison between the U.S. non-oil trade balance (which is overwhelmingly manufactured goods) and U.S. manufacturing employment:

Until the late 1990s, employment in manufacturing, although steadily falling as a share of total employment, had remained more or less flat in absolute terms. But manufacturing employment fell off a cliff after 2000, and this decline corresponded to a sharp increase in the non-oil deficit.

Does the surge in the trade deficit explain the fall in employment? Yes, a lot of it. A reasonable estimate is that the deficit surge reduced the share of manufacturing in GDP by around 1.5 percentage points, or more than 10%, which means that it explains more than half the roughly 20% decline in manufacturing employment between 1997 and 2005.

This is over a relatively short time period and focuses on absolute employment, not the employment share. Trade deficits explain only a small part of the long-term shift toward a service economy. But soaring imports did impose a shock on some U.S. workers, which may have helped cause the globalization backlash.

Rapid Globalization and Disruption

The pro-globalization consensus of the 1990s, which concluded that trade contributed little to rising inequality, relied on models that asked how the growth of trade had affected the incomes of broad classes of workers, such as those who didn't go to college. It's possible, and probably even correct, to think of these models as accurate in the long run. Consensus economists didn't turn much to analytic methods that focus on workers in particular industries and communities, which would have given a better picture of short-run trends. This was, I now believe, a major mistake — one in which I shared a hand.

It should have been obvious that the politics of globalization were likely to be much more influenced by the experience of individual sectors that gained or lost from shifting trade flows than by big questions of how trade affects the global blue-collar/white-collar wage gap or the broad statistical measure of inequality known as the aggregate Gini coefficient.

This is where the now-famous 2013 analysis of the "China shock" by David Autor, David Dorn and Gordon Hanson comes in. What they mainly did was shift focus from broad questions of global income distribution to the effects of rapid import growth on local labor markets, showing that these effects were large and persistent. This represented a new and important insight.

To make partial excuses for those of us who failed to consider these issues 25 years ago, at the time we had no way to know that either the hyperglobalization that began in the 1990s or the trade-deficit surge a decade later were going to happen. And without the combination of these developments, the China shock would have been much smaller. Still, we missed a crucial part of the story.

A Case for Protectionism?

What else did the 1990s consensus miss? A lot. Developing-country exports of manufactured goods grew far beyond their level at the time that consensus emerged. The combination of this rapid growth and surging trade imbalances meant that globalization produced far more disruption and cost for some workers than the consensus had envisaged.

-- via my feedly newsfeed