INteresting take on the decline of traditional expertise as AI and automation assume many decision making routines.

In the faint predawn light, the ship doesn't look unusual. It is one more silhouette looming pier-side at Naval Base San Diego, a home port of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. And the scene playing out in its forward compartment, as the crew members ready themselves for departure, is as old as the Navy itself. Three sailors in blue coveralls heave on a massive rope. "Avast!" a fourth shouts. A percussive thwack announces the pull of a tugboat—and 3,000 tons of warship are under way.

To hear more feature stories, see our full list or get the Audm iPhone app.

But now the sun is up, and the differences start to show.

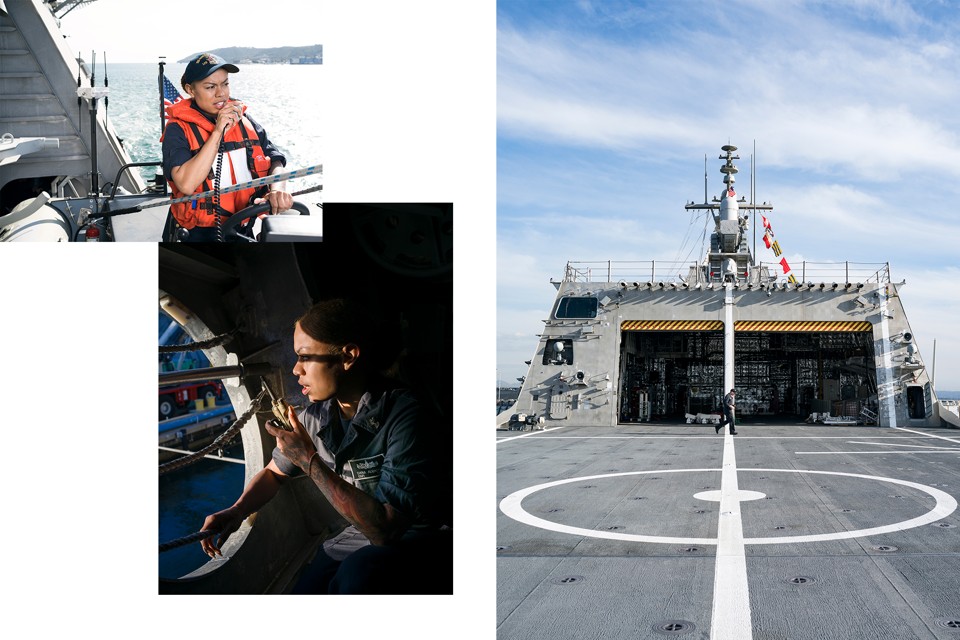

Most obvious is the ship's lower contour. Built in 2014 from 30 million cans' worth of Alcoa aluminum, Littoral Combat Ship 10, the USS Gabrielle Giffords, rides high in the water on three separate hulls and is powered like a jet ski—that is, by water-breathing jets instead of propellers. This lets it move swiftly in the coastal shallows (or "littorals," in seagoing parlance), where it's meant to dominate. Unlike the older ships now gliding past—guided-missile cruisers, destroyers, amphibious transports—the littoral combat ship was built on the concept of "modularity." There's a voluminous hollow in the ship's belly, and its insides can be swapped out in port, allowing it to set sail as a submarine hunter, minesweeper, or surface combatant, depending on the mission.

The ship's most futuristic aspect, though, is its crew. The LCS was the first class of Navy ship that, because of technological change and the high cost of personnel, turned away from specialists in favor of "hybrid sailors" who have the ability to acquire skills rapidly. It was designed to operate with a mere 40 souls on board—one-fifth the number aboard comparably sized "legacy" ships and a far cry from the 350 aboard a World War II destroyer. The small size of the crew means that each sailor must be like the ship itself: a jack of many trades and not, as 240 years of tradition have prescribed, a master of just one.

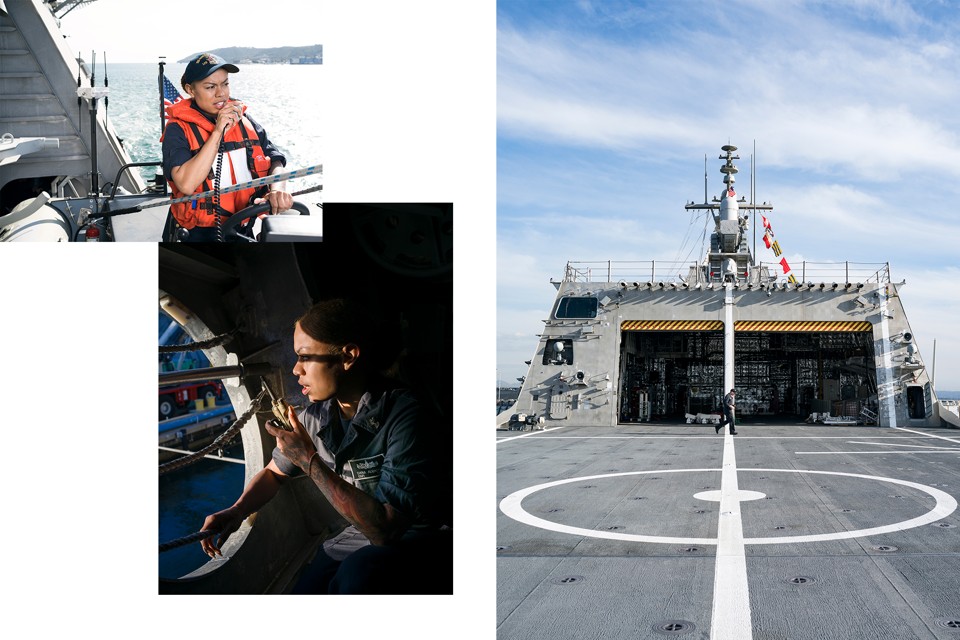

On most Navy ships, only a boatswain's mate—the oldest of the Navy's 60-odd occupations—would handle the ropes, which can quickly remove a finger or foot. But none of the three sailors heaving on the Giffords's ropes is a line-handling professional. One is an information-systems technician. The second is a gunner's mate. And the third is a chef. "We wear a lot of hats here," Culinary Specialist 2nd Class Damontrae Butler says. After the ropes are put away, he reports to the ship's galley, picks up a basting brush, and starts readying a tray of garlic bread for the oven.

Two boatswain's mates are on hand, but only to instruct and oversee—and they too wear lots of hats, between them: fire-team leader, search-and-rescue swimmer, crane operator, deck patroller, helicopter-salvage coordinator. The operative concept is "minimal manning." On the bridge, five crew members do the jobs usually done by 12, thanks to high-tech display screens and the ship's several thousand remote sensors. And belowdecks, once-distinct engineering roles—electrician's mate, engine man, machinist, gas-turbine technician—fall to the same handful of sailors.

The USS Gabrielle Giffords at dock in San Diego (Peter Bohler)

Minimal manning—and with it, the replacement of specialized workers with problem-solving generalists—isn't a particularly nautical concept. Indeed, it will sound familiar to anyone in an organization who's been asked to "do more with less"—which, these days, seems to be just about everyone. Ten years from now, the Deloitte consultant Erica Volini projects, 70 to 90 percent of workers will be in so-called hybrid jobs or superjobs—that is, positions combining tasks once performed by people in two or more traditional roles. Visit SkyWest Airlines' careers site, and you'll see that the company is looking for "cross utilized agents" capable of ticketing, marshaling and servicing aircraft, and handling luggage. At the online shoe company Zappos, which famously did away with job titles a few years back, employees are encouraged to take on multiple roles by joining "circles" that tackle different responsibilities. If you ask Laszlo Bock, Google's former culture chief and now the head of the HR start-up Humu, what he looks for in a new hire, he'll tell you "mental agility." "What companies are looking for," says Mary Jo King, the president of the National Résumé Writers' Association, "is someone who can be all, do all, and pivot on a dime to solve any problem."

The phenomenon is sped by automation, which usurps routine tasks, leaving employees to handle the nonroutine and unanticipated—and the continued advance of which throws the skills employers value into flux. It would be supremely ironic if the advance of the knowledge economy had the effect of devaluing knowledge. But that's what I heard, recurrently, while reporting this story. "The half-life of skills is getting shorter," I was told by IBM's Joanna Daly, who oversaw an apprenticeship program that trained tech employees for new jobs within the company in as few as six months. By 2020, a 2016 World Economic Forum report predicted, "more than one-third of the desired core skill sets of most occupations" will not have been seen as crucial to the job when the report was published. If that's the case, I asked John Sullivan, a prominent Silicon Valley talent adviser, why should anyone take the time to master anything at all? "You shouldn't!" he replied.

As a rule of thumb, statements out of Silicon Valley should be deflated by half to control for hyperbole. Still, the ramifications of Sullivan's comment unfurl quickly. Minimal manning—and the evolution of the economy more generally—requires a different kind of worker, with not only different acquired skills but different inherent abilities. It has implications for the nature and utility of a college education, for the path of careers, for inequality and employability—even for the generational divide. And that's to say nothing of its potential impact on product quality and worker safety, or on the nature of the satisfactions one might derive from work. Or, for that matter, on the relevance of the question What do you want to be when you grow up?

How deep these implications go depends, ultimately, on how closely employers embrace the concepts behind minimal manning. The Navy, curiously, has pushed the idea forward with an abandon unseen anywhere on land. Within a few years, 35 littoral combat ships will be afloat, along with three minimally manned destroyers of the new Zumwalt class. The effort seemed to me a good test case for the broader questions bedeviling the economy: Can a few brilliant, quick-thinking generalists really replace a fleet of specialists? Is the value of true expertise in serious decline?

[Read: The case against specialists]

I wanted to try to answer these questions—which is why, that morning in San Diego, I joined the crew of the Giffords as it prepared to set sail.

A warship is, in the words of one Navy analysis, a highly complicated "socio-technical system." It operates in an environment that is often hostile, even outside of war; its crew—isolated by vast waters—must be ready for every eventuality. Traditionally, navies handled this by staffing their ships amply. Spain's wood-and-sail Santísima Trinidad carried upwards of 1,000 men at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, providing redundancy in the face of any contingency. If one system failed, there was a backup. This may not have been efficient, but it was effective. The U.S. Navy adopted that model long ago—and has not lost a ship in combat since the Korean War.

But the end of the draft, in 1973, brought rising labor costs and, with them, a shift in thinking. "For my entire 39-year career," the late Admiral Jeremy Boorda said in the early '90s, "we always talked about buying ships and manning them with people … I think we need to think about things differently now. We need to figure out how to have the fewest number of people possible, and then build [ships] to make them as effective as they need to be."

In 1995, Boorda converted an aging cruiser, the USS Yorktown, into an experimental "smart ship" on which watches were combined, engine rooms were unmanned, and sailors communicated by handheld radio instead of stationary telephones. The result was promising but modest: a 4 percent reduction in crew size. A series of naval reports concluded that "big dollar savings" could be achieved only with more significant changes, including greater automation and the selection and training of "generalists rather than specialists."

Then, in 2001, Donald Rumsfeld arrived at the Pentagon. The new secretary of defense carried with him a briefcase full of ideas from the corporate world: downsizing, reengineering, "transformational" technologies. Almost immediately, what had been an experimental concept became an article of faith. In what Ronald O'Rourke of the Congressional Research Service has called "an analytical virgin birth," the Navy committed itself to developing the littoral combat ship and the Zumwalt-class destroyer, using the principles of minimal manning. The LCS came first, partly because it borrowed an Australian design for a passenger ferry and could therefore boost the fleet size quickly.

"I think when the Navy started off, they had a really good plan," Paul Francis, of the Government Accountability Office, told the Senate in 2016. "They were going to build two ships, experimental ships." But in 2005, having assured itself that "optimal manning works," the Navy decided to skip the experimentation and move straight to construction. From this point on, whenever the Navy tried to study the feasibility of minimal manning, its analysis was colored by the fact that—on these ships, at least—it had to work. Dozens of littoral combat ships were on their way. The Giffords was the 10th to deploy.

As the skyline of downtown San Diego receded in the distance, we found ourselves approaching a pier that lay along the final extremity of land before the open Pacific. Shimmering far off to the left was Coronado Beach, the legendary training site for Navy SEALs. To the right was the tower of a nuclear submarine. Our mission for the day was to unload ammunition from the ship to an onshore supply base.

On deck I spotted a man holding a pair of high-tech binoculars and calling out distances: "Three hundred yards. Two hundred yards." Turns out it was Butler, who, in addition to his other jobs, was working to become a certified lookout. "You have to be adaptable, very adaptable to the circumstances, or things can really take a turn in a different direction," he told me, while estimating the distance and bearing of an approaching yacht under the tutelage of another sailor. "For me, that means thinking about the task you're doing, not the task you'll have to do." That is: not dwelling on the garlic bread in the oven. "And asking the right questions. Uh, 500 yards?" He checked his eyeball estimate with the range finder. "Five hundred yards."

What other jobs did he have? Should a fire break out, Butler said, he would become a "boundaryman" and work to stop the spread of smoke to other compartments—a job that, on another ship, would be supervised by a full-time damage-control specialist. The LCS has only two of these—which is one reason it has a "survivability" rating of 1, the lowest score possible. If the ship is critically struck, crew members are expected to simply abandon ship and escape. Traditionalists hate the idea.

Culinary Specialist 2nd Class Damontrae Butler works on deck and in the kitchen. (Peter Bohler)

Butler wasn't the only character to reappear in different form. During an all-hands meeting—the smallness of the group exaggerated by the large size of the flight deck they stood on—someone pointed to the figure strolling in from stage right. It was one of the two boatswain's mates who had been overseeing the line-handlers that morning. He had swapped his blue coveralls for head-to-toe green camo, and was walking back and forth, appearing to survey the upper deck of the ship. Such costume changes gave the whole ship the feel of a small theater troupe in which the actor playing the prince's cousin also plays the apothecary, the friar, and Messenger No. 2.

The Navy knew early on that not just anyone could handle this kind of multitasking. By the early 2000s, the Office of Naval Research was commissioning studies on how to select and prepare a crew for the new ships. One of the academics brought in was Zachary Hambrick, a psychology professor at Michigan State University. Instead of trying to understand how well naval candidates might master fixed skills, Hambrick began to examine how they performed in what are known as fluid-task environments. "We wanted to identify characteristics of people who could flexibly shift," he told me. To that end, in 2010 he administered a test to sailors at Naval Station Great Lakes—and when I traveled to Michigan State to find out more about his work, he invited me to give it a try.

In Hambrick's Expertise Lab, I sat before a screen divided into quadrants: One showed me a fuel gauge that I had to monitor; another displayed a set of letters I had to memorize; another gave me a set of numbers to add together; and the final one presented me with a red button to push whenever a high-pitched tone sounded. All four tasks contributed equally to my total score, which appeared at the center of the screen. Because there really is no such thing as multitasking—just a rapid switching of attention—I began to feel overstrained, put upon, and finally irked by the impossible set of concurrent demands. Shouldn't someone be giving me a hand here? This, Hambrick explained, meant I was hitting the limits of working memory—basically, raw processing power—which is an important aspect of "fluid intelligence" and peaks in your early 20s. This is distinct from "crystallized intelligence"—the accumulated facts and know-how on your hard drive—which peaks in your 50s. In a setting where the possession of know-how is trumped by the ability to acquire it quickly, as in Hambrick's game, fluid intelligence is paramount. (For more on fluid and crystallized intelligence, see "Your Professional Decline Is Coming (Much) Sooner Than You Think," by Arthur C. Brooks, on page 66.)

When the sailors at Naval Station Great Lakes took the test, they were thrown a curveball that I was not: In the middle of the test, the scoring system suddenly changed, so that one quadrant now accounted for 75 percent of the score. Some sailors, Hambrick told me, were quick to spot the change and refocus their attention accordingly. They tended to test high in fluid intelligence. Others noticed the change but continued to devote equal attention to all four tasks. Their scores fell. This group, Hambrick found, was high in "conscientiousness"—a trait that's normally an overwhelming predictor of positive job performance. We like conscientious people because they can be trusted to show up early, double-check the math, fill the gap in the presentation, and return your car gassed up even though the tank was nowhere near empty to begin with. What struck Hambrick as counterintuitive and interesting was that conscientiousness here seemed to correlate with poor performance.

Sailors on the Navy's new littoral combat ships must be able to carry out multiple jobs; the operative concept is "minimal manning." (Peter Bohler)

Hambrick wasn't the only one to observe this correlation. While Jeffery LePine, an Arizona State management professor and former Air Force officer, was doing Navy-funded research on decision making in the late 1990s, he used a computer game a lot like the one Hambrick administered. The tasks were explicitly military (for instance, assessing the "threat level" of 75 aircraft based on speed, altitude, range, etc.) but the curveball was similar: Unbeknownst to the participants, the scoring rules changed partway through the game. When this happened, he noticed that players who scored high on conscientiousness did worse. Instead of adapting to the new rules, they kept doing what they were doing, only more intently, and this impeded their performance. They were the victims of their own dogged persistence. "I think of it as the person literally going down with a sinking ship," LePine told me.

And he discovered another correlation in his test: The people who did best tended to score high on "openness to new experience"—a personality trait that is normally not a major job-performance predictor and that, in certain contexts, roughly translates to "distractibility." To borrow the management expert Peter Drucker's formulation, people with this trait are less focused on doing things right, and more likely to wonder whether they're doing the right things.

High in fluid intelligence, low in experience, not terribly conscientious, open to potential distraction—this is not the classic profile of a winning job candidate. But what if it is the profile of the winning job candidate of the future? If that's the case, some important implications would arise.

One concerns "grit"—a mind-set, much vaunted these days in educational and professional circles, that allows people to commit tenaciously to doing one thing well. Angela Duckworth, a University of Pennsylvania psychology professor, has written powerfully about the value of grit—putting your head down, blocking out distractions, committing over a course of many years to a chosen path. Her writing traces an intellectual lineage that can also be found in Malcolm Gladwell's Outliers, which explains extraordinary success as a function of endless, dedicated practice—10,000 hours or more. These ideas are inherently appealing; they suggest that dedication can be more important than raw talent, that the dogged and conscientious will be rewarded in the end.

In the stable environments Duckworth and Gladwell draw from (chess, tennis, piano, higher education), a rigid adherence to routine can no doubt serve you well. But in situations with rapidly changing rules and roles, a small but growing body of evidence now suggests that it can leave you ill-equipped.

Paul Bartone, a retired Army colonel, seemed to find as much when he studied West Point students and graduates. Traditional measures such as SAT scores and high-school class rank "predicted leader performance in the stable, highly regulated environment of West Point" itself. But once cadets got into actual command environments, which tend to be fluid and full of surprises, a different picture emerged. "Psychological hardiness"—a construct that includes, among other things, a willingness to explore "multiple possible response alternatives," a tendency to "see all experience as interesting and meaningful," and a strong sense of self-confidence—was a better predictor of leadership ability in officers after three years in the field. Thus, Bartone and his co-authors wrote, "traditional predictors [of performance] appear not to hold in the fast-paced and unpredictable operational environment in which military officers are working today."

The world of work is full of such surprises. And as the rules change, so do ideas about what makes a good worker. "Fluid, learning-intensive environments are going to require different traits than classical business environments," I was told by Frida Polli, a co-founder of an AI-powered hiring platform called Pymetrics. "And they're going to be things like ability to learn quickly from mistakes, use of trial and error, and comfort with ambiguity."

"We're starting to see a big shift," says Guy Halfteck, a people-analytics expert. "Employers are looking less at what you know and more and more at your hidden potential" to learn new things. His advice to employers? Stop hiring people based on their work experience. Because in these environments, expertise can become an obstacle. That was the finding of a 2015 study carried out by the Yale researchers Matthew Fisher and Frank Keil, titled "The Curse of Expertise." The more we invest in building and embellishing a system of knowledge, they found, the more averse we become to unbuilding it.

Jeffery LePine has observed this phenomenon in another part of his life. For years, he devoted himself to understanding cars, and amassed a collection of Pontiacs that he maintained himself. But new developments—fuel injection and the like—convinced him that at times he needed expert help. When one of his cars developed a leaky engine, he called in a mechanic whose first attempt to fix the problem was to replace the rear oil seal. The leak persisted, so the mechanic replaced the engine and gave it a new oil seal. Still no luck, so he replaced the whole thing again. Finally, the mechanic read the instructions that came with the oil seal—something a novice would have done at the outset—and learned that newer engines required an extra step. By not doing it, he'd been puncturing the seals and causing new leaks himself.

The Yale study nicely summed up the dynamic at play here: All too often experts, like the mechanic in LePine's garage, fail to inspect their knowledge structure for signs of decay. "It just didn't occur to him," LePine said, "that he was repeating the same mistake over and over."

Yet the limitations of curious, fluidly intelligent groups of generalists quickly become apparent in the real world. The devaluation of expertise opens up ample room for different sorts of mistakes—and sometimes creates a kind of helplessness.

Aboard littoral combat ships, the crew lacks the expertise to carry out some important tasks, and instead has to rely on civilian help. A malfunctioning crane on board one LCS, for example, meant that the crew had to summon an expert to solve the problem, and then had to wait four days for him to arrive.

There have been other incidents. Because of a design flaw, the LCS engines started to corrode not long after the fleet's launch, but for a long time nobody on board noticed, which led to costly delays and repairs. When a congressional oversight committee found out about the problem in 2011, it called the ships' crews to task. Who was in charge of checking the engines? The answer was … nobody. The engine rooms were unmanned by design. Meanwhile, the modular "plug and fight" configuration was not panning out as hoped. Converting a ship from sub-hunter to minesweeper or minesweeper to surface combatant, it turned out, was a logistical nightmare. Variants of all three "mission packages" had to be stocked at far-flung ports; an extra detachment of 20-plus sailors had to stand ready to embark with each. More to the point, in order to enable quick mastery by generalists, the technologies on each had to be user-friendly—which they were not. So in 2016 the concept of interchangeability was scuttled for a "one ship, one mission" approach, in which the extra 20-plus sailors became permanent crew members.

On it went. The crew of one LCS failed to oil the main engine gear (forcing the ship to limp home from Singapore for a $23 million repair). The crew of another put a seal in the wrong hole, flooding its engine with seawater. "Who was responsible for the training?" the late Senator John McCain asked angrily at a hearing. "Wasn't someone?"

A chastened naval command quietly ordered all LCSs to stand down for several months in 2016, sent their engineering crews back to school for requalification, and bulked up its high-tech courseware, which lets LCS trainees practice tasks on a highly detailed virtual ship. ("I'm going to show you the stern tube-shaft seal assembly," a virtual officer announces in one training video, by way of greeting.) Onboard routines were updated to include more oversight and double-checking. The ship passed its sea trials, but not with flying colors. "As equipment breaks, [sailors] are required to fix it without any training," a Defense Department Test and Evaluation employee told Congress. "Those are not my words. Those are the words of the sailors who were doing the best they could to try to accomplish the missions we gave them in testing." The intentionally small crew size made the ship ill-suited to forward combat, because not enough people were on board to stand watch.

These results were, perhaps, predictable given the Navy's initial, full-throttle approach to minimal manning—and are an object lesson on the dangers of embracing any radical concept without thinking hard enough about the downsides. Even if minimal manning works for a given business or institution, the ramifications for society may not be entirely salubrious. Grit and 10,000 hours of training are appealing in part because they reinforce American self-conceptions that have been present since the country's founding, ideas about equality of opportunity, about the value of knowledge, about the importance of hard work. And while no one would suggest that effort itself is being devalued today—hard work is just as important in the workplace that's emerging as in the one that's receding—a world in which mental agility and raw cognitive speed eclipse hard-won expertise is a world of greater exclusion: of older workers, slower learners, and the less socially adept. "This sounds absurd," retired Vice Admiral Pete Daly (now head of the U.S. Naval Institute) told me, "but if you keep going down this road, you end up with one really expensive ship with just a few people on it who are geniuses … That's not a future we want to see, because you need a large enough crew to conduct multiple tasks in combat."

But it's a future we may need to see. As the cost of computing continues to fall and artificial intelligence usurps more and more human competencies, the collapse of old jobs into new ones seems preferable to their total disappearance. (Look at the unmanned helicopter the Giffords can accommodate, and it's distressingly easy to picture a sailorless ship. Already, the DOD worries about the vulnerability of an LCS to "swarm boats"—basically, dozens of explosive-laden speedboats, unmanned and computer-coordinated.)

And while it seems fair to say that the Navy pushed the LCS forward too hard and too heedlessly, calling its minimal-manning project a failure would be premature. The viability of the aircraft carrier was not obvious to military planners in the 1920s, but then, through an extended process of on-site trial and error, engineers added catapults and arresting wires, and reconfigured flight decks, all of which turned an interesting idea into reality. The LCS is likewise the scene of everyday trial, error, and adjustment.

When large vessels stop to dock, for example, they have to be tied up with ropes that are too heavy to throw. So sailors on board throw out smaller ropes that are attached to the big ones, which their colleagues on land can then pull over. On traditional Navy ships, this is done from a ship's top deck—a sailor tosses the small rope over the side, and the rest is easy. This is how it's taught at the Navy's equivalent of boot camp, on a mock wooden ship near Lake Michigan. But on the LCS the ropes reside in the forward compartment, where getting a good side-arm throw out the porthole is next to impossible. One early solution—sending a boatswain's mate up top to make the toss—proved both awkward and complicated. But this is where having a crew attracted to novel problems is useful. At some point, a sailor had the idea of not throwing but launching the line through the porthole. This unknown soul started fiddling with materials at hand, and lo, the "slingshot" came into being: a rubber bungee cord knotted into an X around four carabiners that clip to the inside of a porthole and, when pulled back and then released, have enough strength to send a bundle of rope to a sailor waiting for it on land. A triumph of found materials, it's an indication, however small, of what a group of open-minded generalists can achieve: namely, inventing new patterns of working that turn a lack of expertise into an asset.

Peter Bohler

What does all this mean for those of us in the workforce, and those of us planning to enter it? It would be wrong to say that the 10,000-hours-of-deliberate-practice idea doesn't hold up at all. In some situations, it clearly does. Sports, musicianship, teaching—these are fields where the rules don't change much over time. In tennis, it pays to put in the hours mastering your serve, because you know you'll always be serving to a box 21 feet long and 13.5 feet wide, over a net strung 3.5 feet high. In medicine and law, the rules might change—but specialization will probably remain key. A spinal surgery will not be performed by a brilliant dermatologist. A criminal-defense team will not be headed by a tax attorney. And in tech, the demand for specialized skills will continue to reward expertise handsomely.

But in many fields, the path to success isn't so clear. The rules keep changing, which means that highly focused practice has a much lower return. Zachary Hambrick and his co-authors showed as much in a 2014 meta-analysis. In uncertain environments, Hambrick told me, "specialization is no longer the coin of the realm."

So where does this leave us?

It leaves us with lifelong learning, an unavoidably familiar phrase that, before I began this story, sounded tame to me—a motivational reminder that it's never too late to learn Spanish or enroll in nighttime pottery classes. But when Guillermo Miranda, IBM's former chief learning officer, used the term in describing to me how employees take advantage of the company's automated career counselor, Myca, it started to sound like something new. "You can talk to the chatbot," Miranda said, "and say, 'Hey, Myca, how do I get a promotion?' "

Myca isn't programmed to push any fixed career track. It isn't dumb enough to try to predict the future—much less plan for it. "There is no master plan," Miranda said. Myca just crunches data, notices correlations, and offers suggestions: Take a course on blockchain. Learn quantum computing. "Look, Jennifer!" it might say. "Three people like you just got promoted because they got these badges."

Even as I reported this story, I found myself the target of career suggestions. "You need to be a video guy, an audio guy!" the Silicon Valley talent adviser John Sullivan told me, alluding to the demise of print media. I found it fascinating and slightly odd that Sullivan would so readily imagine that I would abandon writing—my life's pursuit since high school—for a new line of work. More than that, though, I found the prospect of starting over just plain exhausting. Building a professional identity takes a lot of resources—money, time, energy. After it's built, we expect to reap gains from our investment, and—let's be honest—even do a bit of coasting. Are we equipped to continually return to apprentice mode? Will this burn us out? And will the collective work that results be as good as what came before?

A junior officer steers the ship back into port; on the Giffords, even a routine transit back to base is a chance to learn something new. (Peter Bohler)

Those are questions for the long haul. In 20 years, we'll know a lot more about the costs and benefits of minimal manning and lifelong learning. But nobody on the Giffords was pondering that after the crew finished its unloading job. They had to get back to base. So 26 crew members crammed into a briefing room, where they talked tides, collision avoidance, and sea lanes, which would be crawling with pleasure craft this time of day. "If action becomes necessary," said the captain, Shawn Cowan, "take action early."

The ship's bridge was quiet on the way home. As we sailed, I thought back to an encounter I'd had earlier in the day with two engineer's mates. I'd found them in a quiet corner of the cargo bay, testing water samples pulled from the ship's engines for signs of corrosion. We struck up a conversation, and they explained to me that their responsibilities also included maintaining the ship's gas turbines, diesel engines, water jets, and various pumps—for oil, fuel, drinking water. I told them that sounded like a lot. They agreed, but then one of them added that doing so many things was just the way things go in "this LCS business." Not only that, he added, but he was learning so much that he might soon earn a promotion that would put him up on the bridge, in charge of the whole propulsion system.

Everybody I met on the Giffords seemed to share that mentality. They regarded every minute on board—even during a routine transit back to port in San Diego Harbor—as a chance to learn something new. Which is why, near the end of our trip, as we approached the Coronado Bridge, Captain Cowan gave the helm to a junior officer and asked her to steer us under the bridge and into port. The officer looked intently at the nozzles of the ship's four water jets, took in the sight of the approaching bridge, and said, "Very well, Captain."

Then she adjusted her course.

This article appears in the July 2019 print edition with the headline "The End of Expertise."

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Sadly, many of these older workers have had little choice but to accept low-paid, physically demanding work at some of America's richest companies (e.g., Walmart and Amazon) who are delighted to take advantage of their desperation.

Sadly, many of these older workers have had little choice but to accept low-paid, physically demanding work at some of America's richest companies (e.g., Walmart and Amazon) who are delighted to take advantage of their desperation.