https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2019/04/embedded-internationalism-the-only-way-to-fight-the-global-oligarchy.html

Embedded Internationalism: The Only Way to Fight the Global Oligarchy

Yves here This post may seen a bit abstract, but it attempts to map out how to increase democratic accountability and counter the influence powerful private sector interests have over major international institutions. While another response has been to try to bolster national sovereignity, that can't go very far in a world where economies smaller than the US and China (or ones that are or have been forced to autarkies, like India, Russia, and Iran) operate through regional trade blocs.

The shortcoming of nationalism as a response to how the global wealthy have succeeded in using their ability to arbitrage markets to foment a race to the bottom in environmental, regulatory, and labor standards is that it often winds up being dominated by right wing interests that play upon xenophobia and by design don't address the problems of mobile capital and long supply chains. So "embedded internationalism" isn't quite a solution, it at least helps clarify the nature of the problem and where some approaches might lie.

By David Adler (@davidrkadler), a political researcher. Originally published at openDemocracy

Progressives must urgently develop a new vision for international institutions, or they will be reshaped in the image of our opponents.

This article is part of a series by openDemocracy and the Bretton Woods Project on the crisis of multilateralism. The views expressed are those of the author's only, and are not necessarily representative of either organisation.

A coup is underway at the World Bank, and no one is watching. On Friday, 5 April, the executive directors of the world's most powerful multilateral bank voted unanimously to appoint David Malpass — a staunch supporter of Donald Trump and fierce critic of "globalism" — as its new president.

The decision honoured the 'gentleman's agreement' that allows the US president to install an ally at the helm of the bank — despite a hard-fought campaign to allow for an open selection. The direction of the bank will now be set by a man who believes that multilateralism has "gone substantially too far" to obstruct the America First agenda.

But beyond the pages of the Financial Times, these proceedings have barely dented public discourse. Malpass will begin his five-year term without a single street protest or a single press statement by a major political party.

The silence is puzzling. The World Bank, like its partner the IMF, has huge costs. The United States alone contributes $155 billion of taxpayer money to the bank — more than double what it spends on food stamps each year. These institutions also have huge consequences. As the Bretton Woods Project has revealed, the World Bank and the IMF continue to demand austerity and drive privatization across the global south. The scale and scope of these institutions suggests that their management should invite serious public scrutiny.

But they do not — and this is not an accident. International institutions are intentionally insulated from democratic demands. A very generous reading would suggest that this is because international institutions must be protected from the vagaries of the electoral cycle. Their democratic deficit is, according to this view, a virtue. International institutions could never withstand grassroots intervention.

But this strategy has now — clearly and dramatically — backfired. By closing themselves off from public view, these institutions made themselves easy targets for political entrepreneurs seeking a scapegoat for their domestic crises. The European Union, the United Nations, NATO — international institutions have become the bogeymen of populist movements around the world. There are important reasons to revile these institutions, but they are rarely those cited by the blustering Brexiteers or MAGA chuds.

In other words, if democracy once appeared as the great danger to the integrity of international institutions, technocracy has revealed itself as their true existential threat.

It is time, then, to bring the politics back in — not only as a strategy for building a new internationalism, but also as a necessary defence against the alt-globalist agenda that is climbing its way to the very top of our international institutions, one quiet coup at a time.

II.

But what, exactly, does this mean? How should we make sense of the struggle to reclaim international institutions? And what are the strategies to get there?

To answer these questions, it is helpful to set out the terrain.

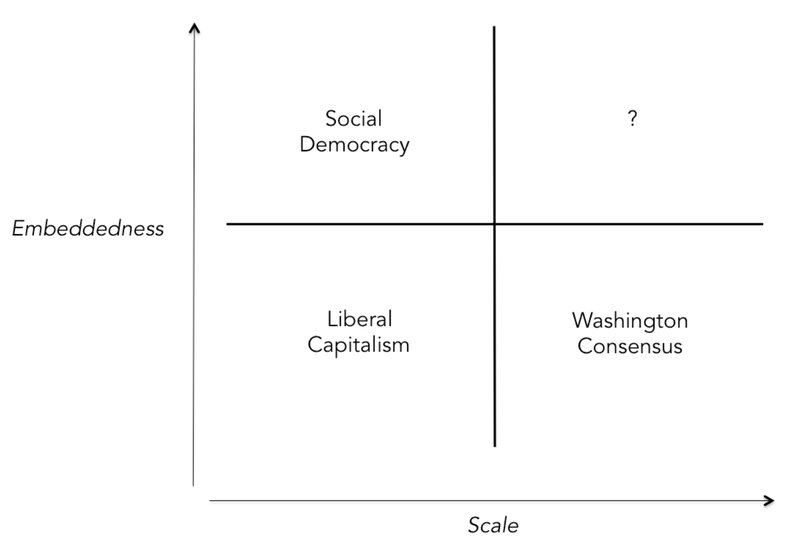

I map the political economy of this struggle across two axes. The first is embeddedness: the extent to which markets are anchored in society. At one end is laissez faire capitalism, a free market unconstrained by moral considerations and economic regulations. Everything here is a commodity, including human life and the earth itself. The axis therefore moves upward toward decommodification, enshrining protections that limit the exploitation of resources like labour and land.

The first axis could also be described by its more modern inverse, financialisation: the extent to which elements of society present themselves as opportunities for financial speculation. To disembed is to financialise. To re-embed is to definancialise.

The second axis is scale: the level at which political activity is organized, from the nationalto the global.

Figure 1: The Axes of Internationalism

The map tells the story of a century of political conflict.

In its first half, the primary conflict occurred along the axis of embeddedness at the national level. A Gilded Age of capitalism witnessed the emergence of a consolidated national bourgeoisie, which built new institutions — peak associations, political machines — to disembed the economy. New workers' movements then organized their own institutions at the national level — trade unions, political parties — in order to demand that governments combat inequality, provide decent jobs, and enshrine new rights to services like healthcare and goods like housing. Social democracy was born.

The latter half of the century activated the second axis. Having been tamed at the national level, capital went global, chasing opportunities in countries where the economy was far less constrained by embedding regulations. Of course, they did not encounter those countries in a natural state of disembeddedness. Rather, this process required the construction and mobilization of institutions that would clear the way for international investors.

The World Bank and the IMF, dangling the carrot of development resources, were refashioned to play this role. Promoting their 'Washington Consensus,' these institutions acted as vehicles for a global disembedding of the economy — both directly, in the cases of countries that agreed to the terms of structural adjustment; and indirectly, in the cases of countries who were forced to compete with them, applying pressure to undo the progress of the social democratic arrangement.

In other words, capital and labour have been caught in a game of cat and mouse across the quadrants of this map. Capital first scurried to enshrine its interests at the national level, then labour caught up and contested. Capital scurried to reconstruct the global economy in its image — but no social movement has emerged to contest it at that scale.

Indeed, in the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2008, new political movements tended to point toward more familiar quadrants of the map. Right-wing populists from Nigel Farage to Donald Trump heralded a new model of national neoliberalism: shifting back on the axis of scale while demanding a deeply disembedded economy — Singapore-on-Thames, or the Trump tax cuts. Their left-wing opponents similarly called to reassert the primacy of the nation, but with much stronger social protections. Globalization, both agreed, had gone too far.

But in calling to return to the nation, the new social democrats failed to learn the lessons of the past. Capital, now globalized, has the upper hand against individual nations that hope to contest it. It can slither between borders, and hide out in havens. The mouse is out of the bag — now we must train the cat to find it.

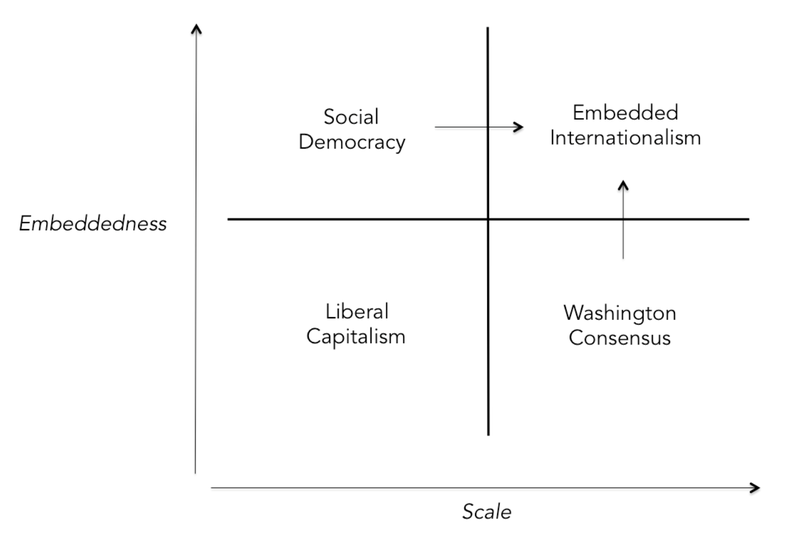

In other words, our task is to push into the missing quadrant — to re-embed the institutions that govern the global economy: an embedded internationalism.

Figure 2: Strategies for Embedded Internationalism

But how, exactly, do we get there?

The map provides some ideas. In particular, it suggests two lines of strategic attack that we must pursue simultaneously.

The first is contestation: igniting a transnational debate that links social movements around the world in a single conversation about our international institutions — scaling up along the x-axis. The last half-century of globalization has made our national debates increasingly alike in content, focused on transnational issues like trade and finance in a global economy. But they remain fragmented in form: few social movements or political parties coordinate their platforms across borders. Scaling up means integrating these national debates to match the scale of their issues.

In a word, we need to get international institutions back on the ballot, calling on progressive politicians to outline their own vision for institutions like the World Bank, IMF, ILO, and the UN.

The second is democratization: demanding reforms that shift power away from the technocrats and toward regular people — re-embedding along the y-axis. We might start by killing the 'gentleman's agreement' that allows the US and the EU to install their allies at the head of the World Bank and IMF, respectively. But we should also call to introduce democratic representation at the heart of these institutions, allowing countries to elect members of their governing council.

These may sound like pipedreams. But the perverse power structure of our international institutions means that a progressive president in the White House or prime minister at Number 10 could radically shift the momentum in favour of these proposals. After all, countries like the US and the UK hold key purse strings. If contestation can push their governments to table serious democratization reforms — to raise the voices of small countries around the world — these proposals will get a hearing.

Of course, not every institution can be salvaged in the process of re-embedding the global economy. Consider the International Finance Corporation (IFC), a wing of the World Bank Group that oversees private sector investment in developing countries. The IFC today acts as little more than an engine for financialisation, turning public wealth into financial products that can be traded across the financial sector. A bold agenda for global re-embedding would simply abolish the IFC full stop.

But new institutions can be proposed in its place. Progressives around the world are crying out to coordinate their demands and fight together to constrain the global oligarchy. All it takes is one progressive government with the courage — and the imagination — to propose new institutions to do so: worker ownership funds, green transition institutions, tax justice authorities. Even proposals that are introduced unilaterally will soon attract international participation. If the US builds it, in particular, they will certainly come.

Critics like Adam Tooze suggest that efforts to reclaim and transform the international institutional order are "quixotic," because the global economy is too fluid, too volatile to be ordered in this way.

But laissez faire was planned, and globalization was, too — and now David Malpass is preparing to remould them. Progressives should take a page from the playbook of their opponents and develop a plan to roll out new institutions for the re-embedding of the economy, rather than simply relying on ad-hoc interventions to roll back the mistakes of the past.

III.

On the eve of Trump's inauguration, the United States was poised to retreat from its role as the driver of global disembedding. The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) was dead. America First was alive. And virtually every international institution had earned the ire of the incoming president. "If the word 'isolationist' has any meaning, [Trump] qualifies as one," the FT reported.

But now we can see that the right-wing populist project is more dangerous than it first appeared. Far from rejecting international institutions — scaling back from the global level to the national one — Trump and his allies are mounting their take-over. The objection to the Washington Consensus, it turns out, was not that it did not serve their interests. It was that it did not serve them well enough. This is what David Malpass means when he says that multilateralism has gone "too far."

It is all too easy for progressives to dismiss international institutions as the machinery of global capital, and to focus where power appears closer at hand.

But we cannot afford to play peek-a-boo politics: just because we don't talk about the World Bank and the IMF doesn't mean that they are not still there. As the mess of Brexit has definitively demonstrated, power at the international level is a prerequisite for sovereignty much lower down, particularly in countries that lack the geopolitical weight to set the international agenda. We must therefore develop our own vision of international institutional change, or else they will be reshaped by our opponents.

The first steps of this strategy are now clear. We must contest globally, reminding people and parties around the world that international institutions are theirs for the taking. And we must demand democracy, reigniting our imagination about how to transform them.

But the prospects for such a transformation are far better than they may appear. The unanimous appointment of an anti-globalist like David Malpass at the helm of a hyper-globalizing institution like the World Bank should be an inspiration to all of us — that radical change may be around the corner.

13 COMMENTS

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Let's work out what's wrong with their half-baked neoliberal ideology and its underlying economics, neoclassical economics.

"Everything is getting better and better look at the stock market" the 1920's sucker that believed in free markets

"Stocks have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau." Irving Fisher 1929.

The 1920's neoclassical economist that believed in free markets knew this was a stable equilibrium.

Better shelve this for a few decades until everyone has forgotten.

Now everyone has forgotten we can use it for globalisation.

I don't know who the architects of globalisation were, but I do know they weren't very bright.

Just because people have forgotten what's wrong with neoclassical economics, it's still got all its old problems.

Running an economy on neoclassical economics.

The 1920s roared with debt based consumption and speculation until it all tipped over into the debt deflation of the Great Depression.

No one realised the problems that were building up in the economy as they used an economics that doesn't look at private debt, neoclassical economics.

What's the problem?

1) The belief in the markets gets everyone thinking you are creating real wealth by inflating asset prices.

2) Bank credit pours into inflating asset prices rather than creating real wealth (as measured by GDP) as no one is looking at the debt building up.

Let's have another go.

https://cdn.opendemocracy.net/neweconomics/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2017/04/Screen-Shot-2017-04-21-at-13.52.41.png

Whoops!

1929 and 2008 look so similar because they are; it's the same economics and thinking.

The global economy never stood a chance.