Saturday, November 3, 2018

Progress Radio:The FACES and PERSONALITIES OF the NAME IN PROGRESS Radio Program

Blog: Progress Radio

Post: The FACES and PERSONALITIES OF the NAME IN PROGRESS Radio Program

Link: http://progress.enlightenradio.org/2018/11/the-faces-and-personalities-of-name-in.html

--

Powered by Blogger

https://www.blogger.com/

How the Economic Lives of the Middle Class Have Changed Since 2016, by the Numbers [feedly]

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/03/upshot/how-the-economic-lives-of-the-middle-class-have-changed-since-2016-by-the-numbers.html

Based on a simplified extrapolation, it works out to about $122 gained a month for a typical family — which for some would be wiped out by higher mortgage rates.

By Neil Irwin

Nov. 3, 2018

Groceries have not gotten much more expensive in the past two years, but carrying debt on a credit card has.CreditElise Amendola/Associated Press

The United States economy is the strongest it has been in ages. Growth has been robust, and the unemployment rate is at generational lows, as new data Friday affirmed.

Yet the Republican Party, which controls the White House and Congress, trails Democrats substantially in polling on which party is preferred.

It helps to look beyond the overall economic data to understand this disconnect. After all, you can't eat G.D.P., and good jobs numbers aren't the same as a place to live.

If you look instead at the actual financial lives of average middle-income families from 2016 — their incomes, spending, assets and debt — and how shifts since Election Day in 2016 would have been likely to affect them, you get a more mixed picture.

Wages haven't risen much. Inflation has been low, helping keep the price of most staple goods down, though with gasoline prices a costly exception. The tax cut has left more money in most middle-class families' pockets, but only a bit.

In terms of assets, the typical middle-income family has either zero or minimal holdings in the stock market, meaning the surge since November 2016 hasn't paid direct benefits. But a majority of households in this income bracket do carry some credit card debt, which has become more expensive amid rising interest rates.

And in terms of housing costs, rents haven't risen much — but a sharp rise in mortgage rates has made homes less affordable for anyone looking to buy.

Add it all up, and while the benefits of a surging economy, tax cuts and the rising stock market are real, they net out to a less favorable economic reality for a family in the middle of the income scale than the economic headlines might imply.

This math is oversimplified — it doesn't reflect how families may have changed their spending and saving patterns in the last two years, and conflates different definitions of middle income. But the back-of-the-envelope results are revealing:

If you take the benefits of higher wages and the lower taxes, subtracting higher costs for consumer goods and higher interest rates on credit card debt — it works out to a gain of $122 a month.

Slow wage growth, a boost from tax cuts, low inflation

A lower unemployment rate may benefit workers by making it easier for someone who loses a job to find a new one. But a defining feature of the expansion for years has been relatively tepid growth in wages.

The median pay for a full-time worker in the United States — now $893 a week — has risen enough since late 2016 to generate an extra $204 a month in pretax earnings for a household with a single earner, a 5.6 percent gain.

Subtract payroll taxes and federal income taxes on that raise, and that family is looking at $158 a month in additional earnings.

The tax cuts enacted at the start of 2018 should mean most middle-income Americans keep a bit more of their earnings. Analysis by the Tax Policy Center found that of the 91 percent of middle-income tax filers who received a tax cut, the reduction averages $910, or about $76 a month.

Wages may not be growing very fast for middle-income people, but the good news is that prices of most of the things they buy have been rising even more slowly.

The Consumer Price Index excluding housing costs is up only 3.2 percent since November 2016, adding about $101 to the monthly expenses of a family with spending patterns that match those of an average family in the middle 20 percent of the income distribution that year.

When you look at individual items that compose a large portion of family budgets, the relatively low inflation comes through.

Grocery prices — "food at home" in the Labor Department's terminology — are up only 1.1 percent in the nearly two years since November 2016, adding $3.33 to the monthly grocery bill for an average family in the middle 20 percent of income.

Outside of food, the pattern mostly recurs. Electricity bills are up 0.42 percent, a mere 50 cents a month of additional expense. Apparel is slightly less expensive than it was in November 2016, saving a middle-class family $1.22 a month. An 11 percent drop in the price of cellphone service saves that family $10.48 each month.

The big exception is gasoline; its price has been marching steadily higher since late 2016. The 23.5 percent run-up in the price of motor fuels adds $37.38 to the typical family's monthly expenses.

Fine time for renters, but higher rates hurt would-be buyers

When it comes to housing, it matters a lot whether you're renting and planning to continue renting; renting but seeking to buy a home; or already own one.

For renters who plan to stay renters, costs are rising modestly, just like overall inflation — 3 percent since November 2016, tacking an extra $26.54 onto monthly costs for the average renter.

ADVERTISEMENT

Homeowners typically have their monthly mortgage costs already set. Their wealth — the value of their home — has risen a bit in two years. The median sale price for a home in the United States was $214,000 in November 2016, according to data from Zillow, and the national appreciation rate since then implies such a house would now be worth $230,000.

Things are trickier for a renter looking to buy a home, because of rising mortgage rates. A side effect of the surging economy and deficit-increasing tax cuts has been higher rates, which means that even though home prices aren't up all that much in the last two years, the cost for a buyer needing credit is considerably higher.

The rate on a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage was 3.5 percent at election time two years ago, and is now 4.83 percent. Combined with the rise in the price of the median home, a middle-income American family looking to buy with 20 percent down would be looking at a monthly mortgage payment that is $196 a month higher now than in November 2016, wiping out gains from higher wages and lower taxes.

A market boom for a few, and higher interest rates for others

The Trump administration has pointed to the booming stock market as evidence of success: The Standard & Poor's 500 index has returned about 29 percent, including reinvested dividends, since November 2016.

But middle-income families typically have minimal direct exposure to the stock market. Their financial holdings tend to be modest at best, meaning that rising stock prices create only a small wealth increase.

Among middle-income families in 2016, only 52 percent held stocks either directly or indirectly, such as through a mutual fund. And of those 52 percent, median stock holdings were only $15,000. (That would be up to around $19,000 now if they left the money in an S.&P. 500 index fund since then without making further contributions.)

Stock investments are much more a feature of upper-income brackets. The same survey showed that 94.7 percent of families in the top 10 percent of income held stocks, with a median value of $363,400.

ADVERTISEMENT

Many middle-income Americans, 84.3 percent of them, do tend to hold some form of debt. And rising interest rates in the Trump economy — a consequence of strong economic growth and Federal Reserve actions meant to prevent the economy from overheating — are making that debt more costly.

In 2016, 53 percent of middle-income households had credit card debt, with an average debt balance of $4,400. The average rate on such debt has risen to 16.5 percent today from 13.6 percent in November 2016, implying an extra $10.50 a month in interest cost for a family carrying that balance.

In other words, debtors — and the average middle-class American fits that description — are paying a price for the surging economy even as they enjoy the benefits of higher pay and low inflation.

Given the limitations in the data on which these calculations are based, it's best to think of this analysis as an impressionistic painting rather than a high-resolution photograph of the economic lives of the middle class.

But it is a telling one, and helps explains the limits of a political message built on what seems to be a booming economy. It booms for some people more than others.

How we did the math

To develop this portrait, we started with two government surveys from 2016: the Labor Department's Consumer Expenditure Survey, which provides details of household spending patterns broken down by income bracket, and the Federal Reserve's Survey of Consumer Finances, which details assets and debt.

Then, we simply extrapolated forward to the fall of 2018. If those patterns among middle-class families held steady as they were buffeted by economywide forces, would they be better or worse off in the days before the midterms?

This is assuming that they had no radical changes to their financial lives like getting a lucrative new job or winning the lottery, and that their wages, costs and investment performances plugged along at average rates over the last 23 months.

Because of limitations in the data available for the recent past, we had to combine data sources that aren't really meant to be combined. We had to switch between different definitions of middle income, and we made some simplifying assumptions. (For example, we calculated how higher gasoline prices would increase people's spending without adjusting for how they might react to higher prices by driving less.)

Neil Irwin is a senior economics correspondent for The Upshot. He previously wrote for The Washington Post and is the author of "The Alchemists: Three Central Bankers and a World on Fire." @Neil_Irwin • Facebook -- via my feedly newsfeed

Economic Update - US "Sugar Arrangements” Industry [feedly]

https://economicupdate.podbean.com

Updates on latest foreign and US elections, the CEA document against socialism, growing inequality of billionaires' wealth, army represses report on costs and errors of Iraq war, and expose of Maine's subsidy for corporations by helping indebted students. Interview with Dr. Harriet Fraad on the US "Sugar Arrangements" industry.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Commentary: Trump Administration Rules on Health Waivers Weaken Pre-Existing Condition Protections [feedly]

https://www.cbpp.org/health/commentary-trump-administration-rules-on-health-waivers-weaken-pre-existing-condition

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Friday, November 2, 2018

Another strong jobs report yields critical insights [feedly]

http://jaredbernsteinblog.com/another-strong-jobs-report-yields-critical-insights/

The nation's payrolls added 250,000 jobs last month, the unemployment rate held steady at a 49-year low, the closely watched labor force participation rate increased, and year-over-year wage growth broke 3 percent for the first time since 2009. Given that inflation has been running a bit short of 2.5 percent, this means workers are finally seeing real gains in the buying power of their paychecks.

Wages were up 3.1 percent for all private sector workers and 3.2 percent for middle-wage workers, suggesting that the tight labor market is generating broad gains, not just helping those at the top of the earnings scale.

One slight caveat re wage growth is that in the previous October (2017), hourly pay in this series fell four cents in nominal terms, a rare event. Thus, the base off to which this October's wage gain is compared was unusually low. However, the moving-average figures below, which smooth out such monthly noise, show clear acceleration in the pace of wage gains. Also, averaging over the past three months shows hourly wages growing at a very strong 3.6 percent annual rate compared to the prior three months. This represents a clear acceleration over the prior two "quarters," when annualized growth was 2.6 and 3 percent, respectively.

In other words, the U.S. job market is tighter than it has been in decades and this dynamic is revealing at least two important insights. The first, which we knew, is that slack matters: the absence of full employment saps worker bargaining power and constrains wage growth. When we move toward full capacity in the job market, workers get back some of the clout they lacked, and employers must share more of the gains with them.

Second, and this most economists did not know, is that there was and still probably is more room-to-run in the labor market than conventional wisdom believed and thus more room for non-inflationary gains. The distributional implications of this critical insight cannot be overstated: full employment provides the biggest gains to the least advantaged, too many of whom have long been left behind in previous economic expansions.

Our monthly smoother, which averages over 3, 6, and 12-month windows to get a better look at the underlying trend of job growth, shows that trend job gains are north of 200,000, more than enough to push our already low unemployment rate down even further. Is this trend persists, and even if it fades some, it will likely take the jobless rate down to below 3.5 percent in coming months.

As noted, the tighter job market has delivered faster wage growth. The smooth trend in the next two figures show a slow staircase of wage gains, from around 2 percent in 2013, to 2.5 percent around 2016, to closing in on around 3 percent now. Contrast this staircase with the "elevator down" shortly after the recession. This pattern of sharp wage-growth losses and slow wage-growth gains is precisely why it is so important for policy makers to preserve and build on the gains generated by the close-to-full-capacity job market.

This admonition is especially the case when we consider how "anchored" price growth has been. The next figure shows that as the unemployment rate has fallen well below the Fed's estimate of the "natural rate"—the lowest rate they believe to be consistent with stable inflation—price growth remained at the Fed's 2 percent target. This anchored inflation dynamic has held even as wage growth has picked up.

Based on these relationships, I and others have suggested the Fed consider pausing in their interest-rate hiking campaign. This is a unique moment for a truly data-driven Fed to build on these critically important labor market gains that are finally—nine years into the expansion—deliver some potentially lasting gains to middle- and low-wage workers.

Finally, a political note. In applauding this strong report a few days ahead of a uniquely important midterm, it is impossible (for me, at least) to discuss the current job market apart from its political implications. First, one reason for the very tight labor market is the tax cut and spending bills that were added to the deficit, which at 4 percent of GDP, is far higher than it should be at this stage of the recovery. This deficit spending is boosting the growth rate by perhaps a percentage point, which I (along with most other economists) believe will start to fade later next year.

In other words, the policy agenda of piling onto the budget deficit when the economy is already closing in on full employment has, to its credit, revealed more labor capacity than most economists and the Fed believed was available. But it is also robbing the U.S. Treasury of much needed revenue at a time when we're going to need more, not less, revenues to meet the fiscal challenges we face.

Moreover, Trump is clearly building on trends he inherited. His constant refrain that the job market was terrible before he got here is the fakest of fake news. And then there's the reckless trade policy, the hateful rhetoric with its murderous consequences, the chaotic dysfunction at the highest levels, and the never-ending stream of lies.

I like a full employment labor market as much—surely more—than anyone. But I guarantee you it's possible to achieve it without all the hate.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

US Payrolls Rise More Than Forecast as Wage Gains Hit 3.1% [feedly]

Every US Metal Producer Is Down for the Year, Despite Tariffs [feedly]

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-11-01/stock-losses-pile-up-at-u-s-metalmakers-trump-sought-to-protect

The largest U.S. aluminum and steel producers -- companies that were supposed to benefit from tariffs -- have all lost value this year.

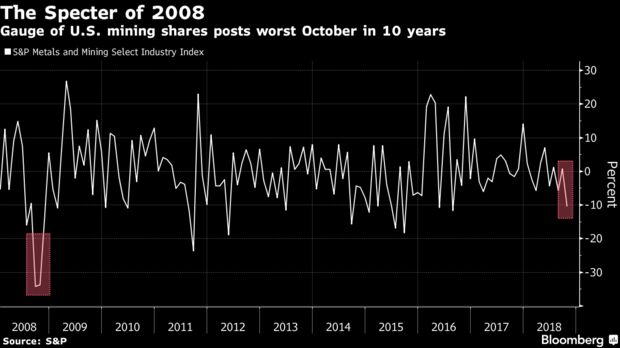

Shares of every major U.S. steel and aluminum producer are down for the year, while Century Aluminum Co. and Alcoa Corp., the country's two biggest aluminum makers, had the worst October since 2008. It was the biggest October drop since 2009 for U.S. Steel Corp., which reports quarterly earnings Thursday afternoon. The sell-off last month outpaced a broader market slump in the worst month for global equities in more than six years.

Companies in metals and mining have been hit especially hard amid concern that the rising trade frictions from the tariffs have helped crimp economic growth. That's eroded metal prices that initially surged when the U.S. announced the levies. The S&P Supercomposite Steel Index has slid 8 percent this year, and fell further behind stock-market gauges in October.

The S&P Metals and Mining Select Industry Index, which tracks 29 U.S. metal and mining companies including Alcoa, lost more than 10 percent last month on its biggest October sell-off since 2008. Chicago-based Century, TimkenSteel Corp. and AK Steel Holding Corp. were among the worst performers.

Caterpillar Inc., the top mining-equipment maker, posted its largest October drop in 10 years.

"The verdict the market has been rendering the past few weeks is this uneasiness and anxiety about the overarching macroeconomic picture, and there are increasing questions about the stress points emerging in the global economy," John Mothersole, an analyst for IHS in Washington, said in a telephone interview.

On Thursday, the S&P metals and mining gauge rose as much as 2.3 percent as U.S. equities rallied amid signs that the Trump administration will ease its trade war with China.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

West Virginia GDP -- a Streamlit Version

A survey of West Virginia GDP by industrial sectors for 2022, with commentary This is content on the main page.

-

John Case has sent you a link to a blog: Blog: Eastern Panhandle Independent Community (EPIC) Radio Post: Are You Crazy? Reall...

-

---- Mylan's EpiPen profit was 60% higher than what the CEO told Congress // L.A. Times - Business Lawmakers were skeptical last...

-

via Bloomberg -- excerpted from "Balance of Power" email from David Westin. Welcome to Balance of Power, bringing you the late...