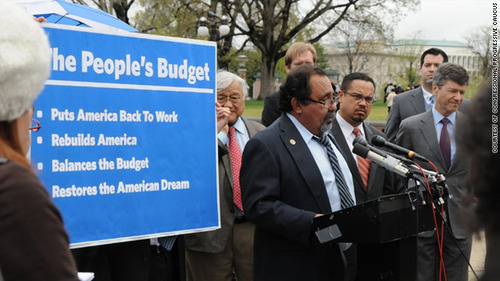

Congressional Progressive Caucus presenting its platform

"If you know the enemy and know yourself, your victory will not stand in doubt; if you know Heaven and know Earth, you may make your victory complete."

–Sun Tzu, The Art of War

By Carl Davidson

Keep On Keepin' On

Successful strategic thinking starts with gaining knowledge, particular gaining adequate knowledge of the big picture, of all the political and economic forces involved (Earth) and what they are thinking, about themselves and others, at any given time. (Heaven). It's not a one-shot deal. Since both Heaven and Earth are always changing, strategic thinking must always be kept up to date, reassessed and revised.

To make a political assessment of the forces commanded by the U.S. bourgeoisie and its subaltern allies and strata, it helps to make an examination of Congress, the White House and other Beltway institutions, as well as voting trends and others political and cultural among the masses. And to get an accurate estimation, we must often tear away, set aside or bracket misleading labels and frames, as well as assess varying economic resources and voting results. We want to illuminate an intentionally obfuscated landscape, like when a flash of lightning at night does away with shadows and renders the landscape in sharp relief.

The primary conventional wisdom we want to dissect here is that the U.S. has a two-party system. First, the nature of political parties in the US today is rather unique; they are not parties in any European parliamentary sense, where members are bound to a program or platform with some degree of discipline, and mass party organizations exist at the base. Second, the Republicans and the Democrats in the US are largely empty shells locally, consisting mainly of incumbents and staffers, and their retained lawyers, fundraisers and media consultants. There is some variation from state to state–state committeemen and women will pass resolutions and certify ballot status and positions, but there's not much of a mass character save for an occasional campaign rally. Third, at the Congressional level the two-party structure, to some degree, still allows for dividing the spoils of committee assignments, but even these are often warped by other considerations.

A few also like to argue that the US has only one party, a capitalist party, with two wings, the bad and the worse. But this is reductionist to a fault, and doesn't tell you much other than that we live in a capitalist society, which is rather trivial.

Some also hold out hope for a 'third party' that is noncapitalist. But given the 'winner take all' rules in most elections, along with the amount of money and resources required to mount credible campaigns, these are long shots, save for periods of crisis and upheaval, like the period just before the U.S Civil War, where the Whigs imploded, the Liberty Party had a role, and a new 'First Party' formed, the GOP. Another period worth a deeper look is 1944-48, when the rising forces of the Cold War and Southern racism led to a four-way race in 1948 between the Dixiecrats (Strom Thurmond), the Democrats (Harry Truman), the GOP (Thomas Dewey) and the Progressive Party (Henry Wallace).

Our Six-Party System

But today, we'll do better to get a more accurate picture of our adversaries if we set aside the labels of 'two-party system', 'Democrats' and 'Republicans' and the other nuances mentioned above. Instead, I'll offer an alternative working hypothesis, that we live under a six-party system with two labels, and that this will give us a closer and more realistic view of the relation and balance of forces with which we have to deal. But even here, it's important to note that we are discussing 'parties' as clusters of colluding and contending blocs of interests, economic views and social coalitions, not unified and disciplined ideological formations strictly bound to a platform. The six 'parties' described here below, however, do come closer to these kinds of constructs than the larger 'two labels' they operate under.

So who are they?

The Tea Party. So far, only the most far right group has been given the label 'party' in the mass media, even though it operates as a faction within the GOP. It generally represents anti-globalist nationalism with a prominence given to the 'Austrian School' economics of classical liberalism and, in some cases, the self-interest philosophy of Ayn Rand. It also merges with paleo-conservative traditionalists, which serves as a cover for defending white and male privilege and armed militia groups. It appeals to about 10-20 percent of the electorate, with greater support in the South and West. It is currently locked in a fierce factional struggle with the other wing of the GOP. While a minority in the House overall, they dominate the GOP House Caucus, and thus, as reported widely on 24-hour news cycles, they can and do block many bills from coming to the floor. Tea Party incumbents have been aided in gaining and retaining their seats by GOP-led redistricting on the level of the states they control, breaking up districts electing Democrats and forming new one with more homogenous rightwing majorities. This was begun by Paul Weyrich of the 'New Right' under Reagan, and continues to this day

The Republican Multinationalists. These are the neoliberal moneybags of the GOP (and the neoconservative subset termed 'The War Party' by Pat Buchanan and Ron Paul from the right)-the Bushes, Cheney, Karl Rove, the Koch brothers and others with fortunes rooted in petroleum, defense industries and other US businesses with global reach. Their neoliberal economics became hegemonic with Reagan's ascendancy via the anti-Black and anti-feminist 'Southern Strategy' alliance with the forces that later came to make up the Tea Party right. The Koch brother's money also helped form ALEC, the American Legislative Exchange Council, thus allowing business lobbyists to write uniform reactionary legislation, mainly on the state level, across the country. Despite statewide gains, the GOP label's current dilemma is that the Tea Party's more inane, backward and proto-fascist views on social and cultural issues is causing the GOP tickets to lose national elections, deadlock the Congress and strain the alliance. On the other hand, if the 'Country Club' Republicans dump the Tea Party, the GOP itself may implode

The Blue Dogs. This caucus in the Democratic Party is tied to 'Red State' mass voting bases-the military industrial workers, and the Southern and Appalachian regions. They are neo-Keynesian on military matters, but neoliberal on everything else. Their 'party' frequently sides with the GOP in Congressional voting. The Blue Dog Coalition has recently shrunk from 27 to 14 members, often having paved the way to self-defeat by backhandedly encouraging GOP victories in their districts by attacking Obama and other Democrats.

The 'Third Way' New Democrats. This 'party' of the center right is mainly the U.S. electoral arm of global and finance capital, with the Clintons and Rahm Emanuel as the better known public faces. Formed to break with 'economic populism' of the old FDR coalition, and assert a variety of globalist 'free trade' measures and the gutting of Glass-Steagall banking regulations, this new post-Reagan-Mondale grouping decided to put distance between itself and traditional labor allies. While neo-Keynesian on most matters, it also 'triangulates' with neoliberal positions. Started as the Democratic Leader Council and the 'New Democrat Coaltions. John Kerry is a member of the DLC but President Obama has claimed 'no direct connection,' even though the grouping lists Obama as one of its 'rising stars' The DLC/'New Democrats' essentially speaks for some of the more powerful elements of finance capital under the 'Democratic' label.. It is the dominant view among the Senate Democratic majority.

Old New Dealers. This 'party' is represented by unofficial wealthy Democratic groups like Americans Coming Together, plus the AFL-CIO's Committee on Political Education and others. They take a Keynesian approach to economic matters, and are often critical of finance capital and the trade deals promoted by the globalists. They are also wary of deep defense cuts that would cause layoffs among their membership base. They maintain, however, strong alliances with some civil rights, women's and environmental groups. Their main value to Democratic tickets is their independent get-out-the-vote operations, which can be decisive in many races. They also work closely with the Alliance for American Manufacturing, a business-based anti-free trade lobby that works with labor.

PDA/Congressional Progressive Caucus. While the largest single caucus in the House, the CPC 'party' is still relatively small, representing 80 out of 435 votes. Its policy views are Keynesian and, in some cases, social-democratic as well. Its recent 'Back-to-Work Budget' serves as an excellent economic platform for a popular front against finance capital. It also largely overlaps with the Hispanic and Black Caucuses, and is the most multinational 'Rainbow' grouping in the Congress. It also includes Senator Bernie Sanders, the sole socialist in Congress, who was an initial founder of the CPC. It has opposed the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, under the Progressive Democrats of America banners of 'Healthcare Not Warfare' and 'Windmills Not Weapons.' It has recently gained some direct union support from the militant National Nurses United and the Communications Workers of America. Many, but not all, CPC members are also members of Progressive Democrats of America, an independent PAC dubbed the 'Tom Hayden/ Dennis Kucinich' Democrats at the time of their founding in 2004. The Congressional Progressive Caucus is the closest political group the US has that would parallel some of the 'United Left' socialist and social democratic groups in European countries

What Does It All Mean?

With this brief descriptive and analytical mapping of the upper crust of American politics, many things begin to fall in place. Romney, a very wealthy representative of the Multinational GOP group, defeated all the Tea Party candidates in the primaries, and consequently, could never convince the Tea Party he was one of them, simply because he wasn't. This led to a drop in GOP voter enthusiasm that couldn't even be overcome with 'dog whistle' appeals to racism and revanchism in the campaigns.

The Obama administration, on the other hand, at its core, represents an alliance between the DLC 'Third Way' and the Old New Dealers, while also pulling along the PDA/Congressional Progressive Caucus as energetic but critical secondary allies. The Blue Dogs found themselves out in the cold from the wider Obama coalition, and shrank accordingly. Barbara Lee of PDA and the CPC, moving from a minority of one on Afghanistan at the start of the invasion, finally got a majority of House Democrats to oppose and push Obama on the wars, but to little avail in any immediate sense, being thwarted by both the DLC and the Multinational GOP.

This 'big picture' also reveals much about the current budget debates, which are shown to be three-sided-the extreme austerity neoliberalism of the Tea Party Ryan budget, the 'austerity lite' budget of the DLC-dominated Senate Democrats, and the left Keynesian progressive 'Back to Work' budget of the Congressional Progressive Caucus. The 'Old New Dealers' were caught in the middle, with only 20 or so coming over on the Black Caucus version of the 'Back to Work' budget, which was still in the minority.

While all this shows why and how Obama was able to pull together a majority electoral coalition, it also reveals why he is still thwarted on pulling together an effective governing coalition. Likewise, it shows how the Tea Party, with only 10-20 percent of the electorate, is able to water down or completely bloc common-sense measures on gun control with 70-90 percent support among the general population.

Finally, the fact that there is only one avowed socialist in Congress tells us something about our own position in the overall balance of forces. Socialist candidates are only able to draw 2% to 5% of the votes in this period, save for Sanders, and we all know that Vermont has some unique features that made it possible, not that Sanders didn't do yeoman work in pulling together a progressive majority that elected him.

In summary, here are a few things to keep in mind. If you decide to intervene in electoral work to build independent working class grassroots organizations, you don't go 'inside the Democratic Party'. There's not much of an 'inside' there anymore. What you do instead is join or work with one of the two factions/'parties' that are left of center. Your aim is to make either of these stronger, preferably the PDA/Congressional Progressive Caucus. Then to shift the overall balance of forces, your task is to defeat the Tea Party, the Multinational GOP, and the Blue Dogs. At present, not a single piece of progressive legislation is going to get passed without driving a wedge between the two parties under the GOP label and weakening both of them.

We have to keep in mind, however, that 'shifting the balance of forces' is mainly an indirect and somewhat ephemeral gain. It does 'open up space', but for what? Progressive initiatives matter for sure, but much more is required strategically. We are interested in pushing the popular front vs. finance capital to its limits, and within that effort, developing a socialist bloc. If that comes to scale, the 'Democratic Party Tent' is likely to collapse and implode, given the sharper class contractions and other fault lines that lie within it, much as the Whigs did in the 19th Century. That demands an ability to regroup all the progressive forces into a new 'First Party' alliance able to contend for power

An old classic formula summing up the strategic thinking of the united front and popular front is appropriate here: 'Unite and develop the progressive forces, win over the middle forces, isolate and divide the backward forces, then crush our adversaries one by one.' In short, we have to have a policy and set of tactics for each one of these elements, as well as a strategy for dealing with them overall. Finally, a note of warning from the futurist Alvin Toffler: 'If you don't have a strategy, you're part of someone else's strategy.'

Harpers Ferry, WV