Sunday, July 8, 2018

Saturday, July 7, 2018

Shakespeare on tyranny [feedly]

http://understandingsociety.blogspot.com/2018/06/shakespeare-on-tyranny.html

Stephen Greenblatt is a literary critic and historian whose insights into philosophy and the contemporary world are genuinely and consistently profound. His most recent book returns to his primary expertise, the corpus of Shakespeare's plays. But it is -- by intention or otherwise -- an important reflection on the presidency of Donald Trump as well. The book is Tyrant: Shakespeare on Politics, and it traces in fascinating detail the evolution and fates of tyrants through Shakespeare's plays. Richard III gets a great deal of attention, as do Lear and Macbeth. Greenblatt makes it clear that Shakespeare was interested both in the institutions of governance within which tyrants seized power, and the psychology of the tyrant. The parallels with the behavior and psychology of the current US President are striking.

Here is how Greenblatt frames his book.

"A king rules over willing subjects," wrote the influential sixteenth-century Scottish scholar George Buchanan, "a tyrant over unwilling." The institutions of a free society are designed to ward off those who would govern, as Buchanan put it, "not for their country but for themselves, who take account not of the public interest but of their own pleasure." Under what circumstances, Shakespeare asked himself, do such cherished institutions, seemingly deep-rooted and impregnable, suddenly prove fragile? Why do large numbers of people knowingly accept being lied to? How does a figure like Richard III or Macbeth ascend to the throne? (1)So who is the tyrant? What is his typical psychology?

Shakespeare's Richard III brilliantly develops the personality features of the aspiring tyrant already sketched in the Henry VI trilogy: the limitless self-regard, the lawbreaking, the pleasure in inflicting pain, the compulsive desire to dominate. He is pathologically narcissistic and supremely arrogant. He has a grotesque sense of entitlement, never doubting that he can do whatever he chooses. He loves to bark orders and to watch underlings scurry to carry them out. He expects absolute loyalty, but he is incapable of gratitude. The feelings of others mean nothing to him. He has no natural grace, no sense of shared humanity, no decency. He is not merely indifferent to the law; he hates it and takes pleasure in breaking it. He hates it because it gets in his way and because it stands for a notion of the public good that he holds in contempt. He divides the world into winners and losers. The winners arouse his regard insofar as he can use them for his own ends; the losers arouse only his scorn. The public good is something only losers like to talk about. What he likes to talk about is winning. (53)

One of Richard's uncanny skills—and, in Shakespeare's view, one of the tyrant's most characteristic qualities—is the ability to force his way into the minds of those around him, whether they wish him there or not. (64)Greenblatt has a lot to say about the enablers of the tyrant -- those who facilitate and those who silently consent.

Another group is composed of those who do not quite forget that Richard is a miserable piece of work but who nonetheless trust that everything will continue in a normal way. They persuade themselves that there will always be enough adults in the room, as it were, to ensure that promises will be kept, alliances honored, and core institutions respected. Richard is so obviously and grotesquely unqualified for the supreme position of power that they dismiss him from their minds. Their focus is always on someone else, until it is too late. They fail to realize quickly enough that what seemed impossible is actually happening. They have relied on a structure that proves unexpectedly fragile. (67)One of the topics that appears in Shakespeare's corpus is a class-based populism from the under-classes. Consider Jack Cade, the lying and violent foil to The Duke of York.

Cade himself, for all we know, may think that what he is so obviously making up as he goes along will actually come to pass. Drawing on an indifference to the truth, shamelessness, and hyperinflated self-confidence, the loudmouthed demagogue is entering a fantasyland—" When I am king, as king I will be"—and he invites his listeners to enter the same magical space with him. In that space, two and two do not have to equal four, and the most recent assertion need not remember the contradictory assertion that was made a few seconds earlier. (37)And what about the fascination tyrants have with secret alliances with hostile foreign powers?

Third, the political party determined to seize power at any cost makes secret contact with the country's traditional enemy. England's enmity with the nation across the Channel—constantly fanned by all the overheated patriotic talk of recovering its territories there, and fueled by all the treasure and blood spilled in the attempt to do so—suddenly vanishes. The Yorkists—who, in the person of Cade, had pretended to consider it an act of treason even to speak French—enter into a set of secret negotiations with France. Nominally, the negotiations aim to end hostilities between the two countries by arranging a dynastic marriage, but they actually spring, as Queen Margaret cynically observes, "from deceit, bred by necessity" (3 Henry VI 3.3.68).How does the tyrant rule? In a word, badly.

The tyrant's triumph is based on lies and fraudulent promises braided around the violent elimination of rivals. The cunning strategy that brings him to the throne hardly constitutes a vision for the realm; nor has he assembled counselors who can help him formulate one. He can count—for the moment, at least—on the acquiescence of such suggestible officials as the London mayor and frightened clerks like the scribe. But the new ruler possesses neither administrative ability nor diplomatic skill, and no one in his entourage can supply what he manifestly lacks. His own mother despises him. His wife, Anne, fears and hates him. (84)Several things seem apparent, both from Greenblatt's reading of Shakespeare and from the recent American experience. One is that freedom and the rule of law are inextricably entangled. It is not an exaggeration to say that freedom simply is the situation of living in a society in which the rule of law is respected (and laws establish individual rights and impersonal procedures). When strongmen are able to use the organs of the state or their private henchmen to enact their personal will, the freedom and liberties of the whole of society are compromised.

Second, the rule of law is a normative commitment; but it is also an institutional reality. Institutions like the Constitution, the division of powers, the independence of the judiciary, and the codification of government ethics are preventive checks against arbitrary power by individuals with power. But as Greenblatt's examples show, the critical positions within the institutions of law and government are occupied by ordinary men and women. And when they are venal, timid, and bent to the will of the sovereign, they present no barrier against tyranny. This is why fidelity to the rule of law and the independence of the justice system is the most fundamental and irreplaceable ethical commitment we must demand of officials. Conversely, when an elected official demonstrates lack of commitment to the principles, we must be very anxious for the fate of our democracy.

Greenblatt's book is fascinating for the historical context it provides for Shakespeare's plays. But it is even more interesting for the critical light it sheds on our current politics. And it makes clear that the moral choices posed by politicians determined to undermine the institutions of democracy are perennial, whether in Shakespeare's time or our own.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Trade war and depression [feedly]

https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2018/07/06/trade-war-and-depression/

Today is a threshold date for the global economy. Trump's US administration starts imposing trade tariffs on $34bn of imports from China. And Beijing is set to target an equal amount in retaliation. Add that to the pile of tariffs and counter-tariffs growing across the Atlantic and North America, and the value of trade covered by the economic wars that Trump has launched will race through the $100bn mark by today.

And that's just the beginning. This escalating trade war could easily surge through the trillion-dollar mark, taking 1.5% of global GDP. It would be equivalent to a quarter or more of the US's $3.9tn total trade with the world last year and at least 6% of global merchandise trade (worth $17.5tn in 2017, according to the World Trade Organization).

The $34bn in Chinese imports being targeted by the Trump administration today are roughly equivalent in value to a month of imports from China. In this tranche, a 25% import tax will be applied on 818 products ranging from water boilers and lathes to industrial robots and electric cars. In return, Beijing charge a similar tariff on a list that includes soya beans, seafood and crude oil. Both countries have also issued further product lists that would take the total trade covered to $50bn on each side.

Angered by China's retaliation, Trump has ordered a further $200bn worth of imports to be targeted for a 10% tariff and threatened to go for another $200bn beyond that. To which Beijing has vowed its own response. US imports from China were worth $505bn last year while US exports to China reached a record $130bn. So a £450bn rise in tariffs will sweep across much of China's imports.

The Trump auto wars could be worth even more than $600bn. In a televised interview on Sunday the US president called his plan to impose tariffs on imported cars and parts in the name of US national security "the big one". And that is certainly how the EU and others see it. According to official data, the US imported $192bn in cars and light trucks in 2017 and a further $143bn in parts for a total of $335bn.

Then there's NAFTA. The US trades more with Canada and Mexico ($1.1tn) than it does with China, Japan, Germany and the UK combined. Trump is seeking to renegotiate it just as a leftist and nationalist President AMLO has been elected in Mexico. Trump seems to believe the auto tariffs will give him leverage over the EU and Japan in trade negotiations as well as over Canada and Mexico in the continuing talks over an updated North American Free Trade Agreement. Mr Trump is dialling up the pressure to force capitulation. For that reason, the US could impose 20% tariffs on some or all of those imports.

Then there is FART. Trump is planning a bill through Congress, called the Fair and Reciprocal Tariff Act, or FART for short. FART would allow Trump to abandon the World Trade Organization's tariff rules, granting him new authority to unilaterally change tariff agreements with certain countries; to abandon central WTO trade rules, namely the "most favoured nation" principle that keeps countries from setting different tariff rates for different countries outside of free trade agreements and "bound tariff rates," the tariff ceilings that each WTO member country has previously agreed to. In short, it would give Trump the authority to start a trade war without Congressional oversight, all while flouting the WTO's rules. It would mean the end of the WTO, in essence. Already, at least one prominent Trump backer, Trump's short-lived communications director Anthony Scaramucci, tweeted that FART "stinks." But the smell is getting worse.

Any US tariffs are likely to be met with retaliation. EU officials have been working on a plan to target upwards of €10bn in US goods for retaliation if it goes ahead with tariffs on the $61bn in cars and parts it imported from the EU in 2017. But in the extreme scenario — of like-for-like, tit-for-tat tariffs — more than $650bn in global trade would be covered, with consequences for companies globally.

What is the likely impact on global growth from this trade war? Well, Paul Krugman, Keynesian economist, won the Nobel prize in economics for his work on international trade and recently he did a 'back of the envelope' calculation. Krugman reckons that "there's a pretty good case that an all-out trade war could mean tariffs in the 30-60% range; that this would lead to a very large reduction in trade, maybe 70%"! And the overall cost to the world economy would be about a 2-3% reduction in world GDP per year – in effect wiping out more than half of current global growth of about 3-4% a year (and the latter assumes that there is no new global recession).

Krugman reminds us that in the Great Depression of the 1930s, the trade war launched by the US with the Smoot-Hawley tariff, pushed tariffs up to 45%. "So both history and quantitative models suggest that a trade war would lead to quite high tariffs, with rates of more than 40% quite likely." Remember current global trade tariff rates are about 3-4% only.

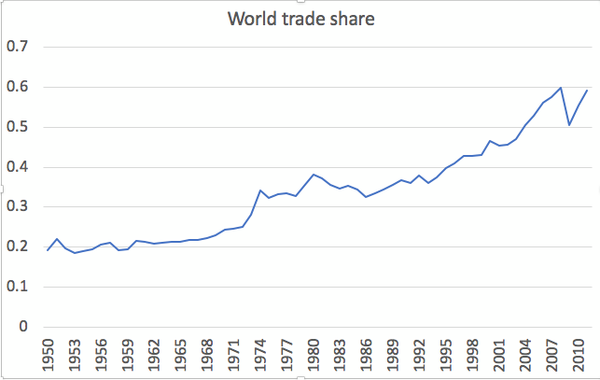

Already, world trade has been staggering from the impact of the Great Recession and the subsequent Long Depression. And world trade share (share of trade in global GDP) has stagnated at about 55% (see figure below). Indeed, the great era of globalisation is over. Now the trade war – another consequence of the Great Recession and the Long Depression since 2008 – could roll back the world trade share to 1950s levels, according to Krugman. "If Trump is really taking us into a trade war, the global economy is going to get a lot less global."

Given this, Krugman looked at the hit to US economic growth. He reckoned it could take 2% of GDP off real growth each year. As average growth is expected to be about 2% a year over the next five years (assuming no world slump), that would mean the US economy would stagnate. That is not as bad as the Great Recession, which knocked 6% of US real GDP growth, but it's bad enough to sustain a further leg of the current Long Depression.

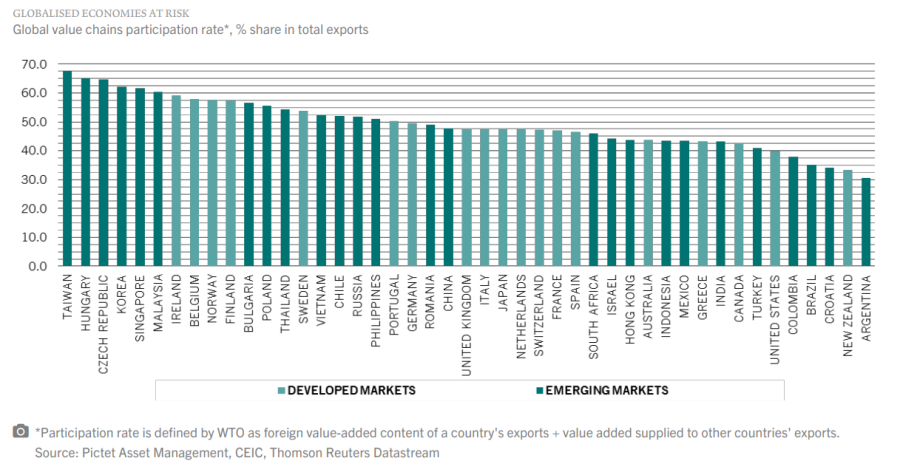

And other countries will be hit even harder. Several major economies rely on trade much more than the US and Europe for growth. In the league of global value chain for trade, Taiwan is top with nearly 70% of value-added coming from exports; and many Eastern European countries also have high export ratios. The US is only at 40% and indeed China is under 50%.

According to Pictet asset management, if a 10% tariff on US trade were fully passed onto the consumer, global inflation would rise by about 0.7%. This, in turn, could reduce corporate earnings by 2.5% and cut global stocks' price-to-earnings ratios by up to 15%. All of which means global equities could fall by some 15-20%. In effect, this would put world stock market price back by three years – indeed a crash.

Meanwhile, Asian governments, led by China, are continuing their drive to relax trading restrictions among themselves, while retaliating to Trump's trade war. Last week, the 16-nation Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, which includes China, Japan and India but not the US, met in Tokyo to try and complete a new trade pact that would include the 10 members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations as well as South Korea, Australia and New Zealand, and cover one third of the world's economy and almost half its population.

And of course, as I have argued previously, China is driving forward its belt and road global investment scheme across central Asia. So, although many Asian and Eastern European economies may suffer more than the US initially from a global trade war, longer term, trade pathways may alter to make them more Euro-Asia centric, to the detriment of the US and Latin America.

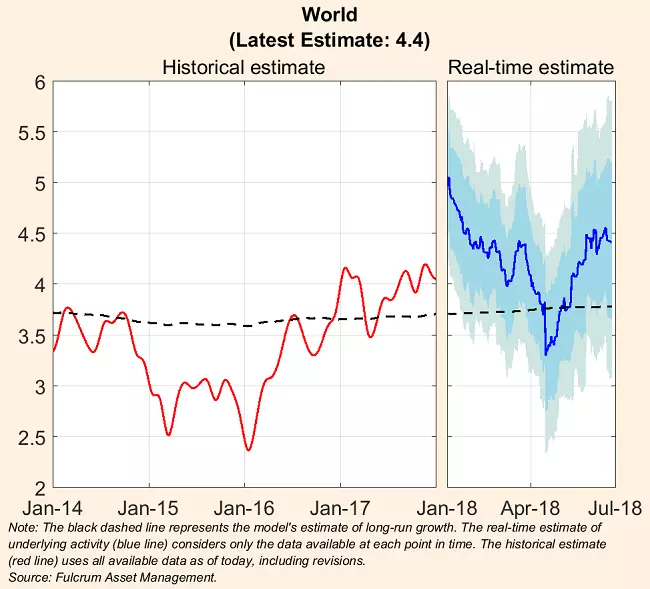

Global growth has been picking up in the last 12 months after a near-recession in 2015-16. Indeed, Gavyn Davies, FT economics blogger and former Goldman Sachs chief economist, reckoned that world growth was growing at 4.4%, about 0.6% above trend, and a full percentage point higher than a couple of months ago.

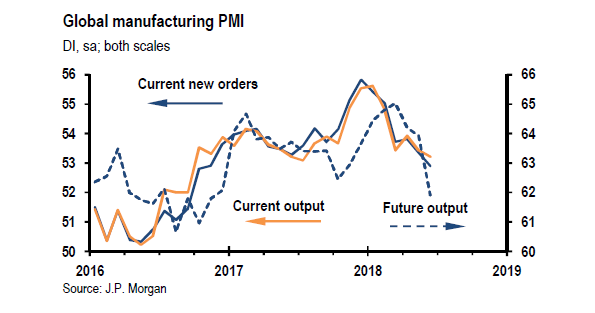

But the trade war will particularly hit the manufacturing and productive sectors of the major economies. And while global growth as a whole may have picked up recently, world manufacturing growth is looking frail. The global manufacturing PMI measures activity in manufacturing and anything over 50 means growth. So not looking so rosy.

Indeed, the US stock market has not bounced very much because, counteracting the one-off rise in corporate profits, has been the possibility of rising interest rates driving up the cost of borrowing and servicing existing debt and the potential hit from the coming trade war.

Hopes for a sharp rise in productive investment from the tax cuts appear dashed. Instead of more investment, there has been a three-fold increase ($150bn) is share buybacks. In Q1 alone, US corporations collectively repatriated $217bn of their international stashes, around 10% of the $2.1trn of greenbacks estimated to be currently offshore. But JPMorgan calculates only $2bn of the $81bn repatriated in Q1 by the top 15 companies was spent on productive investment.

World economic growth (and US growth may have peaked in Q2 2018 and now there is the prospect of an all-out trade war.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Why Mexican Farmers Are Hopeful About López Obrador’s Win [feedly]

http://triplecrisis.com/why-mexican-farmers-are-hopeful-about-lopez-obradors-win/

Timothy A. Wise

The victory of Andrés Manuel López Obrador and his Morena party in Sunday's Mexican elections has stunned international observers. The center-left insurgency received an estimated double the votes of its nearest rival in a multi-party presidential race, winning more than 50 percent of the vote, several important governorships including the first woman to run Mexico City, and an absolute majority in the House of Representatives and the Senate. However the final tally ends up, López Obrador has a resounding mandate for change.

Many observers have interpreted the results as a vote against rampant corruption; given the pervasive graft and influence-peddling in Mexico, López Obrador's clean, austere reputation was certainly a factor for voters. But economic factors also motivated many voters, especially farmers. The majority of Mexicans have been left behind in a failing strategy to hitch the country's fortunes to open trade with the United States under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

As one recent report summarized, "Poverty is worse than a quarter century ago, real wages are lower than in 1980, inequality is worsening, and Mexico ranks 18th of 20 Latin American countries in terms of income growth per person in 21st century." It is hard to imagine worse outcomes in a country with privileged and historic access to the largest capital and consumer markets in the world—the U.S.

Among those rejoicing now over López Obrador's victory are Mexico's farmers, who have been largely abandoned by the government while unregulated imports of below-cost maize, wheat, pork, and other agricultural goods flooded Mexican markets under NAFTA. (See my report.) After the agreement took effect in 1994, maize farmers endured a 400-percent increase in imports of U.S. maize priced 19-percent below its costs of production, resulting in a punishing 66-percent drop in producer prices. Producers of other farm goods faced similar pressures, forcing many to become migrant workers in the strawberry fields of multinational growers or migrate to the U.S. without documentation.

Many placed their faith in López Obrador after he endorsed the Plan de Ayala 2.0, a radical platform put forward in early 2018 by a revitalized farmers' movement. Echoing the platform, López Obrador on the campaign trail called for a return to self-sufficiency in maize and other basic food crops, a reduction in import dependence on the U.S., a shift away from chemical-intensive industrial agriculture and genetically modified crops toward more sustainable practices, and a decisive reorientation of government farm subsidies toward small and medium-scale producers. No wonder rural communities turned out in droves for Morena.

What Farmers Expect

A mobilized farmers' movement will expect and demand action on key planks in their platform to revitalize rural Mexico. Soon after López Obrador takes office on December 1, they expect quick action on several key issues:

- Food self-sufficiency. López Obrador has promised to have farm subsidies directed to small and medium-scale farmers (those with fewer than 50 acres), a radical shift from programs that have overwhelmingly favored large farms. He can make good on that promise by shifting ProAgro subsidy payments to those farmers and making credit and crop insurance available to them.

- Support prices for key crops. López Obrador has promised minimum support prices for key food crops, to give farmers stable and remunerative prices so they can invest in their farms and raise productivity. He can act immediately on that promise.

- Expanding public procurement. One proven way to support local farmers and provide healthier foods is to expand public purchases for schools and other public institutions.

- Redirecting funds to support native maize farmers. The MasAgro Program, a government-funded effort to increase small-scale maize and wheat production, is ineffective and seeks to replace native maize varieties with commercial seeds on some 12 million acres of maize land. That is at odds with López Obrador's pledge to support native maize and tortillas. Reforming MasAgro would be a good place to start.

- Investing in national seed research and production. López Obrador can address transnational monopolization of Mexican seed markets by restoring the nation's capacity to breed and produce its own seeds. Successive neoliberal governments have reduced support for INIFAP, the national agricultural research institute.

- Withdrawing Mexican government support for genetically modified (GM) maize. The current government has supported Monsanto and other seed companies in their campaign to grow GM maize in Mexico. Citizen groups and the courts have prevented the controversial move citing threats to Mexico's native maize varieties. (See my earlier article.) López Obrador can end the controversy by withdrawing government approval of the companies' permits.

Whither NAFTA?

In the campaign, López Obrador was careful, never threatening to pull out of NAFTA and vowing to continue negotiations to improve the current agreement. Since his election, he has vowed to stay the course on negotiations. That won't sit well with his farmer base. Massive, unregulated imports of cheap U.S. commodities, dumped on the Mexican market at prices below the costs of production, are incompatible with López Obrador's commitments to food self-sufficiency, food sovereignty, and investments in small farms and native crops. There are a number of measures he can take immediately:

- Slap retaliatory tariffs on maize and other key food crops. López Obrador can announce his intentions to include maize among the products on which Mexico retaliates after President Trump's unilateral duties on aluminum, steel, and perhaps cars. That would send a strong message that he stands with his maize farmers, and it would give producers relief from dumping-level prices while the government puts in place its full policies for food and agriculture.

- Impose countervailing duties for U.S. dumping. Mexico can justify duties on U.S. crops dumped at below the cost of production. Maize has been coming into Mexico at 12-percent below production costs, justifying a commensurate tariff on imported maize.

- Regulate GM maize imports under the Cartagena Protocol. Mexico can more closely regulate imports of U.S. maize, which is almost all GM, by invoking the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety, which allows importers to require strict labeling and other control measures.

Of course, López Obrador can also call President Trump's bluff on ending NAFTA. The farmers' movement has called for Mexico to withdraw from the agreement unless there are meaningful improvements, and not the kind Trump wants. Mexico may well have less to lose from such a move than the U.S. Mexican farmers certainly wouldn't shed many tears if their new president could once again protect them from dumped U.S. exports.

For once, Mexican farmers have a lot to look forward to.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

More solid job gains, but no real wage growth [feedly]

http://jaredbernsteinblog.com/more-solid-job-gains-but-no-real-wage-growth/

In the latest solid report on the conditions in the US labor market, payrolls grew by 213,000 in June, and labor force participation ticked up two-tenths, as more people were pulled into the improving labor market. This led to a two-tenths tick-up in the unemployment rate to 4 percent (really, 30 basis points up, from 3.75% to 4.05%). Wage growth stayed at 2.7 percent, the same pace as last month, and the average since last December. It is also worth noting that inflation is now growing at about the same rate as wages, so, in one of the less impressive aspects of the current job market recovery, real hourly pay is flat.

As the economic expansion that began in June of 2009 enters its tenth year, the enduring recovery has moved the job market closer to full employment. However, the key message from this report, is that despite many economic estimates to the contrary, there still appears to be room-to-run. That is, various indicators suggest we're closing in on full employment, but not quite there yet. These indicators include:

–Average job gains of about 200,000 per month over the past year (see JB's official jobs-day smoother which averages monthly payroll gains over different intervals). The historical pattern is for the pace of job gains to slow more than it has when we're getting to full capacity in the labor market.

–Though wage growth has clearly ticked up a bit—it has moved from 2 percent, to 2.5, to now, 2.7 percent—it has not picked up as much as we'd expect at full employment. Our current low productivity growth regime is a constraining factor, and we're certainly hearing a lot from employers about labor shortages. But before we take that age-old complaint, we need to see more wage pressure. Employers almost always complain about labor shortages, yet the data suggests they've been quite reluctant to raise pay to get and keep the workers they need.

–The fact that the unemployment rate has long been below the rate most economists believe to be consistent with stable inflation means we should be seeing inflation growing much faster than has been the case. As noted, price growth has ticked up with wage growth, but the Fed's preferred price gauge is only now growing at their target level of 2 percent (note: unlike the deflator I applied to wages above, this gauge leaves out energy and food prices).

Turning back to the closely watched wage series, the two figures below show the annual growth rates in nominal private sector hourly pay and the pay for middle-wage workers (blue-collar manufacturing workers and non-managers in services). The six-month moving average in both cases reveal the recent acceleration as tightening job market has given wage earners more bargaining clout.

But as the next figure shows, inflation has ticked up as well (I forecasted the value for the June CPI as it isn't out yet), and is now growing at the same rate as the hourly pay of middle-wage workers.

The punchline is that real hourly pay is flat, which should not be the case as we enter year 10 of this expansion. A lot of working families are legitimately asking when they can expect to benefit from what is billed in the financial and political pages as a uniquely robust recovery.

Factory jobs got a nice bump, up 36,000 in June, and I saw no evidence in the report of industries in the tradeable sector as yet affected by rising trade tensions. However, as our trading partners retaliate with tariffs of their own, and as Trump's tariffs raise the costs of imports that go into to US production (e.g., car parts), employment in the trade-impacted sectors must be on the watchlist.

In sum, the US job-generation machine continues to post impressive numbers. In fact, these gains are consistent with a job market that has more room-to-run than many believe to be the case. But the wage story remains unsatisfying from the perspective of working families, especially when we look at real wage gains, or the buying power of paychecks. Since this is, of course, what matters most to people regarding living standards, we must recognize that the recovery, even in year 10, has yet to reach everyone.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

DeLong: America the Loser

Jul 4, 2018 J. BRADFORD DELONG

Donald Trump's unhinged recent attacks on the iconic motorcycle maker Harley-Davidson distill his larger assault on American democracy. Even if Democrats do manage to retake one or both houses of Congress this November, the damage that Trump and Republican leaders have done to the country's global standing cannot be repaired.

BERKELEY – The Washington Post's Catherine Rampell recently recalledthat when US President Donald Trump held a session for Harley-Davidson executives and union representatives at the White House in February 2017, he thanked them "for building things in America." Trump went on to predict that the iconic American motorcycle company would expand under his watch. "I know your business is now doing very well," he observed, "and there's a lot of spirit right now in the country that you weren't having so much in the last number of months that you have right now."

What a difference a year makes. Harley-Davidson recently announced that it would move some of its operations to jurisdictions not subject to the European Union's retaliatory measures adopted in response to Trump's tariffs on imported steel and aluminum. Trump then took to Twitter to say that he was, "Surprised that Harley-Davidson, of all companies, would be the first to wave the White Flag." He then made a promise that he cannot keep: "… ultimately they will not pay tariffs selling into the EU."

Then, in a later tweet, Trump falsely stated that, "Early this year Harley-Davidson said they would move much of their plant operations in Kansas City to Thailand," and that "they were just using Tariffs/Trade War as an excuse." In fact, when the company announced the closure of its plant in Kansas City, Missouri, it said that it would move those operations to York, Pennsylvania. At any rate, Trump's point is nonsensical. If companies are acting in anticipation of his own announcement that he is launching a trade war, then his trade war is not just an excuse.

In yet another tweet, Trump turned to threats, warning that, "Harley must know that they won't be able to sell back into U.S. without paying a big tax!" But, again, this is nonsensical: the entire point of Harley-Davidson shifting some of its production to countries not subject to EU tariffs is to sell tariff-free motorcycles to Europeans.

In a final tweet, Trump decreed that, "A Harley-Davidson should never be built in another country – never!" He then went on to promise the destruction of the company, and thus the jobs of its workers: "If they move, watch, it will be the beginning of the end – they surrendered, they quit! The Aura will be gone and they will be taxed like never before!"

Needless to say, none of this is normal. Trump's statements are dripping with contempt for the rule of law. And none of them rises to the level of anything that could be called trade policy, let alone governance. It is as if we have returned to the days of Henry VIII, an impulsive, deranged monarch who was surrounded by a gaggle of plutocrats, lickspittles, and flatterers, all trying to advance their careers while keeping the ship of state afloat.

Trump is clearly incapable of executing the duties of his office in good faith. The US House of Representatives and Senate should have impeached him and removed him from office already – for violations of the US Constitution's emoluments clause, if nothing else. Barring that, Vice President Mike Pence should have long ago invoked the 25th Amendment, which provides for the removal of a president whom a majority of the cabinet has deemed "unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office."

And yet, neither Speaker of the House Paul Ryan nor Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell nor Pence has dared to do anything about Trump's assault on American democracy. Republicans are paralyzed by the fear that if they turn on Trump, who is now supported by roughly 90% of their party's base, they will all suffer at the polls in the midterm congressional election this November.

It is nice to think that the election will fix everything. But, at a minimum, the Democratic Party needs a six-percentage-point edge to retake the House of Representatives, owing to Republican gerrymandering of congressional districts. Democrats also have to overcome a gerrymandering effect in the Senate. Right now, the 49 senators who caucus with the Democrats represent 181 million people, whereas the 51 who caucus with the Republicans represent just 142 million people.1

Moreover, the US is notorious for its low voter turnout during midterm elections, which tends to hurt Democratic candidates' prospects. And Trump and congressional Republicans have been presiding over a relatively strong economy, which they inherited from former President Barack Obama, but are happy to claim as their own.

Finally, one must not discount the fear factor. Countless Americans routinely fall victim to social- and cable-media advertising campaigns that play to their worst instincts. You can rest assured that in this election cycle, as in the past, elderly white voters will be fed a steady diet of bombast about the threat posed by immigrants, people of color, Muslims, and other Trump-voter bugaboos (that is, when they aren't being sold fake diabetes cures and overpriced gold funds).

Regardless of what happens this November, it is already clear that the American century ended on November 8, 2016. On that day, the United States ceased to be the world's leading superpower – the flawed but ultimately well-meaning guarantor of peace, prosperity, and human rights around the world. America's days of Kindlebergian hegemony are now behind it. The credibility that has been lost to the Trumpists – abetted by Russia and the US Electoral College – can never be regained.

J. Bradford DeLong is Professor of Economics at the University of California at Berkeley and a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research. He was Deputy Assistant US Treasury Secretary during the Clinton Administration, where he was heavily involved in budget and trade negotiations. His role in designing the bailout of Mexico during the 1994 peso crisis placed him at the forefront of Latin America's transformation into a region of open economies, and cemented his stature as a leading voice in economic-policy debates.

Harpers Ferry, WV

Krugman on the Job Guarantee

More on a Job Guarantee (Wonkish)

By Paul Krugman

Opinion Columnist

July 5, 2018

As I wrote the other day, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez may call herself a socialist and represent the left wing of the Democratic party, but her policy ideas are pretty reasonable. In fact, Medicare for All is totally reasonable; any arguments against it are essentially political rather than economic.

A federal jobs guarantee is more problematic, and a number of progressive economists with significant platforms have argued against it: Josh Bivens, Dean Baker, Larry Summers. (Yes, Larry Summers: whatever you think of his role in the Clinton and Obama administrations, he's a daring, unconventional thinker when not in office, with a strongly progressive lean.) And I myself don't think it's the best way to deal with the problem of low pay and inadequate employment; like Bivens and his colleagues at EPI, I'd go for a more targeted set of policies.

But I'm fine with candidates like AOC (can we start abbreviating?) proposing the jobs guarantee, for a couple of reasons. One is that realistically, a blanket jobs guarantee is unlikely to happen, so proposing one is more about highlighting the very real problems of wages and employment than about the specifics of a solution. Beyond that, some of the critiques are, I think, off base.

Here's the way some of the critiques seem to run: a large share of the U.S. work force – Baker says 25 percent, but it looks like around a third to me – makes less than $15 an hour. So offering these workers a higher wage would bring a huge rush into public employment, implying a very expensive program.

ADVERTISEMENT

What's wrong with this argument? The key point is that all those sub-$15 workers aren't just sitting around collecting paychecks: they're producing goods and (mostly) services that the public wants. The public will still want those services even if the government guarantees alternative employment, so the firms providing those services won't go away; they'll just have to raise wages enough to hold on to their employees, who would now have an alternative.

Now, that doesn't mean zero job loss. Employers might replace some workers with machines; they would have to raise prices, meaning that they would sell less; so private employment might go down.

But all this is true about increases in the minimum wage, too. And we have a lot of evidence on what minimum wage increases do, because we get a natural experiment every time a state raises its minimum wage but neighboring states don't. What this evidence shows is that minimum wage hikes have very little effect on employment.

So if we think of a job guarantee as a minimum wage hike backstopped by a public option for employment, we should notexpect a mass migration of workers from private to public jobs.

ADVERTISEMENT

OK, a couple of caveats. First, while we have a lot of evidence on minimum wage hikes, these have generally been modest, leaving wages well below the level of the proposed federal guarantee. And even the leftiest of economists would agree that a sufficiently high minimum wage – say, $30 an hour – would reduce employment. Is $15 an hour high enough to get us into job-destroying territory? In high-income regions, probably not. But in America's lagging, poorer regions there might be significant job losses.

Second, there are quite a few working-age adults who aren't in the labor force at all, and at least some of them aren't working because they see no job opportunities at all. A federal jobs guarantee might bring a substantial number of these non-working adults back into the work force. This would, of course, be a good thing from a social point of view – in fact, it's kind of the point of the whole program – but could mean having to find work and money for a lot of new public employees.

How many? At its peak in 2001 the prime-aged employment rate was almost 3 percentage points above its current level. If a job guarantee brought such employment back to its peak, that would mean 3 ½ million additional workers. So we could be talking about a lot of people.

So I don't want to minimize the potential problems with a job guarantee. But a wholesale migration from low-paid private to public employment isn't one of those problems.

And to repeat what I said Tuesday, whatever problems you may have with the specifics of AOC's proposals, they're far more sensible than, say, Larry Kudlow or Sam Brownback-style voodoo economics, which passes for mainstream economic thinking on the other side of the aisle.

Harpers Ferry, WV

West Virginia GDP -- a Streamlit Version

A survey of West Virginia GDP by industrial sectors for 2022, with commentary This is content on the main page.

-

John Case has sent you a link to a blog: Blog: Eastern Panhandle Independent Community (EPIC) Radio Post: Are You Crazy? Reall...

-

---- Mylan's EpiPen profit was 60% higher than what the CEO told Congress // L.A. Times - Business Lawmakers were skeptical last...

-

via Bloomberg -- excerpted from "Balance of Power" email from David Westin. Welcome to Balance of Power, bringing you the late...