https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-12-15/how-america-s-inequality-machine-is-firing-the-dow-into-orbit

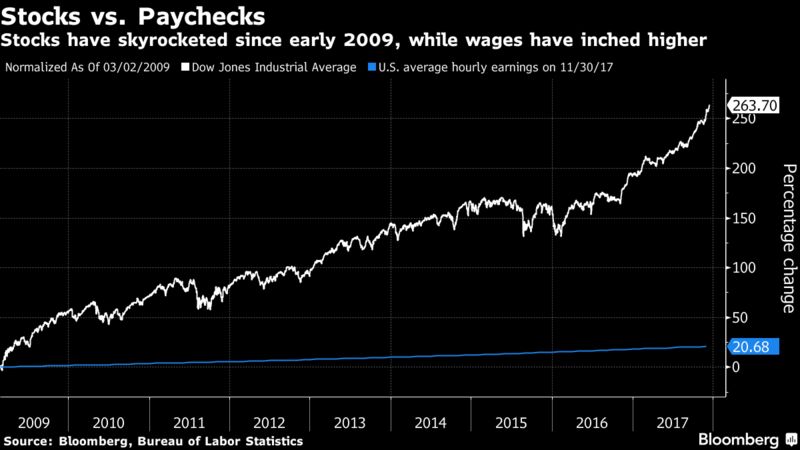

The Great Recession is a speck in the rear-view mirror for America's financial markets. They've advanced far beyond pre-crisis levels. In fact, Goldman Sachs says you can go back a century before 2008, and still not find a "bull market in everything" like today's.

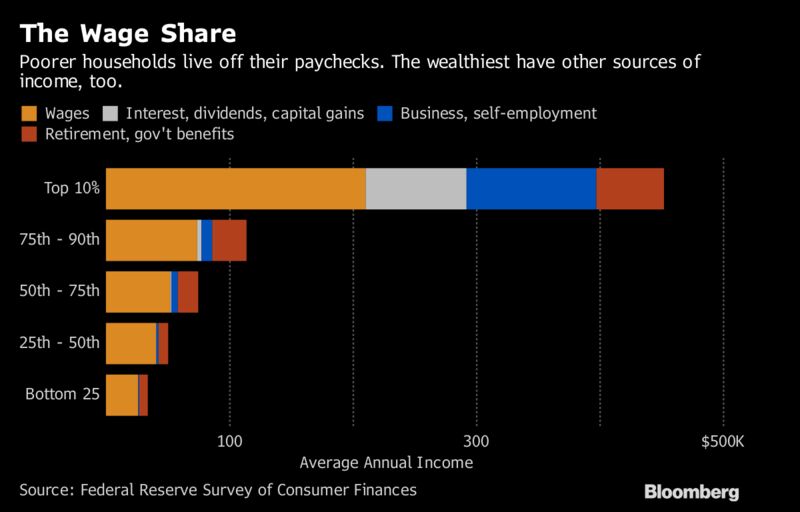

If the real economy had roared back the same way, Donald Trump might not be president. Instead, it's been a grind. While unemployment is near a two-decade low, wages have grown slowly by past standards. They're nowhere near keeping pace with the asset-price surge.

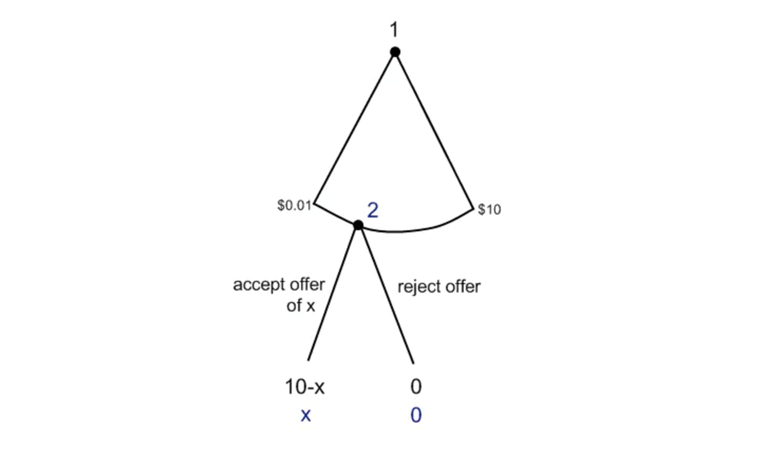

Elected on a promise of better jobs and pay, Trump is about to pull the most powerful lever any government has for firing up the economy: fiscal policy. By slashing taxes on corporate profits, its authors say, the Republican plan will unleash the animal spirits of American business -- and everyone will benefit.

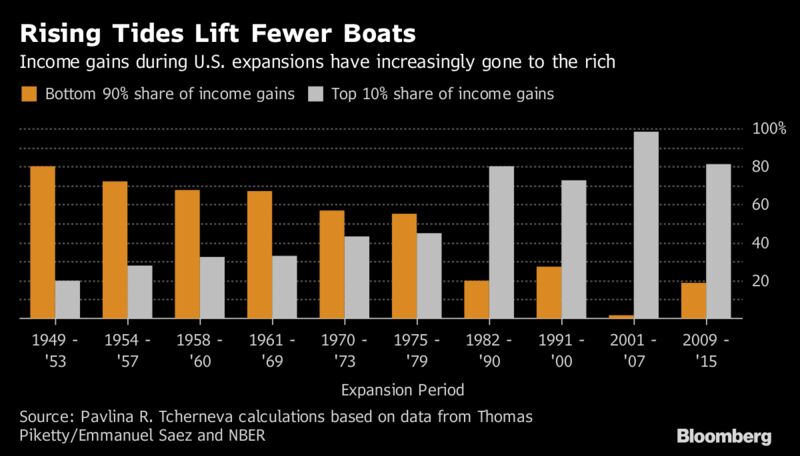

A rising tide does lift all boats -- but nowadays, in the U.S., not equally. Under both parties, recoveries have become increasingly lopsided. The current one has helped millions of people find work; it's also benefited asset-owners far more than people who trade their labor for a paycheck. Income distribution, already the most unequal in the developed world, is getting worse. And that's starting to influence everything from America's spending habits to its elections.

"The story of our time is polarization -- by party, by class and by income," said Mark Spindel, founder and chief investment officer at Potomac River Capital in Washington, and co-author of a 2017 book about the Federal Reserve. "I don't see anything in the tax bill to make that any better.''

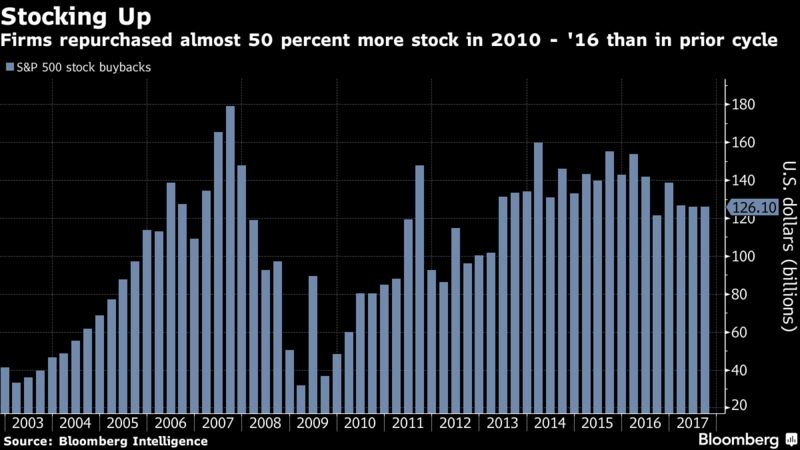

The Fed's post-2008 toolkit included massive purchases of financial assets, which supported a liftoff on the markets but took time to trickle through to the real economy. Trump's tax critics say his plan will have a similar effect, because companies will spend the windfall on share buybacks or dividends, instead of job-creating investments. Plenty of executives say that's exactly what they'll do.

Bank of America's most recent buyback program totals $18 billion. Chairman Brian Moynihan championed the tax proposal this month. "It's good for corporate America, and it's good for us," he said.

There was an echo there of one of the American business world's classic slogans. As applied to the Trump tax cuts, it's highly misleading, according to Nell Minow, vice chair of ValueEdge Advisors.

Good for U.S.?

This isn't a case of "what's good for General Motors is good for the U.S.," said Minow, who's dedicated her career to pushing corporations toward long-term investments in people and businesses. "In my list of the top 100 things companies should do for sustainable wealth creation, buybacks would be number 100."

Companies in the S&P 500 Index bought $3.5 trillion of their own stock between 2010 and 2016, almost 50 percent more than in the previous expansion. The pace has slowed in the last two years. The tax bill could kickstart it.

Buybacks have fueled the stock rally (there's disagreement about how big a part they played). And the rally's biggest benefits go to the richest. On Twitter last week, Trump invited his followers to check their swelling retirement accounts. Only about half the country's households have any such nest-egg.

Soaring markets helped the top 1 percent of Americans increase their slice of the national wealth to 39 percent in 2016, according to the Fed's Survey of Consumer Finances. The bottom 90 percent of families held a one-third share in 1989; that's now shrunk to less than one-quarter.

Republicans are gambling that they can run the economy so hot that companies will hire more workers, and eventually boost their wages. There's a strong argument that the private sector can train them better than government programs can.

'Benefits Everybody'

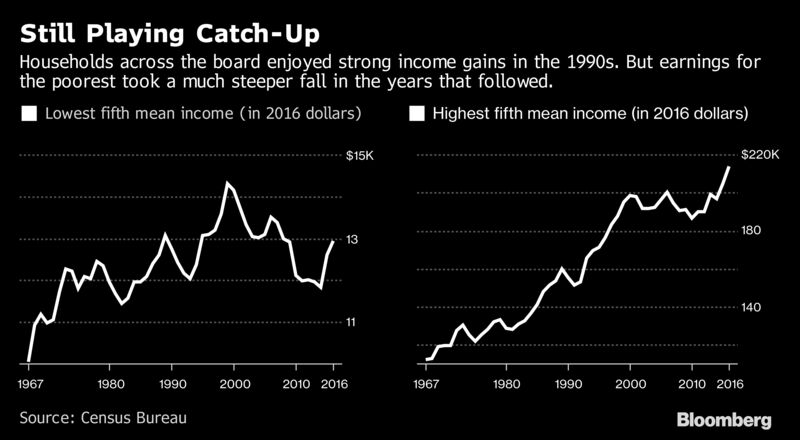

"The more growth we have, the more that benefits everybody," said Ike Brannon, a former Bush administration Treasury official who's now president of Capital Policy Analytics, a consulting firm. "It forces businesses to train people at the fringes." He points to the late 1990s, when growth averaged more than 4 percent and the poorest one-fifth of households saw substantial income gains.

Looming in the background then was a technology-stocks bubble. It burst in March 2000, plunging the economy into recession. What happened next is telling -- it illustrates the perverse asymmetry of bubbles. In the following three years, those poorest households saw their incomes fall more than twice as much as their richest counterparts.

The pattern was repeated after the even bigger housing crash of late 2007. Today, even after an increase of more than 9 percent over two years, incomes at the bottom are short of pre-crisis peaks, while higher earners have comfortably surpassed them.

Companies flush with cash are using it to buy more customers via mergers, or reward capital through dividends, according William Spriggs, chief economist at the AFL-CIO, the country's biggest labor union group. But American workers won't put up with any more business cycles that yield them few gains, he says. "This is the last time they can get away with it, because the backlash is going to be huge."

In the end, the trend toward inequality amounts to capitalist suicide, Spriggs argues. Companies need demand, which requires rising wages so that workers can afford goods and services. "Businesses can't create themselves, they respond to general growth in income," he said. "Inequality chokes off business development."

Support for that kind of argument is surfacing in unlikely quarters.

The International Monetary Fund used to be so entwined with American government thinking that its preferred market-friendly recipe was known as the Washington Consensus. Now, the Fund is cautiously backing redistributive measures -- falling foulof the Trump administration in the process.

In October, the IMF said rich countries can share their prosperity more evenly, without sacrificing growth, by shifting more of the tax burden onto high earners. It warned that "excessive inequality can erode social cohesion, lead to political polarization, and ultimately lower economic growth."

'Broken System'

The U.S. is already experiencing some of those strains.

During last year's election campaign, both major parties effectively broke in half. In both cases, an outsider candidate scored unexpected wins by running against the party establishment, and railing at an economic system they said was rigged against ordinary Americans.

Self-described socialist Bernie Sanders surprised pundits by mounting a serious challenge in the Democratic contest. Trump won his party's nomination and the presidency. He told voters he had experience on the buy-side of American politics, having paid for favors from both parties, and so was well-placed to fix a "broken system" dominated by corporate lobbyists.

Now, Trump is about to hand corporations -- which are already making high profits by historical standards -- a giant tax cut. The bill "addresses problems we don't have, and makes existing problems worse," said Alan Krueger, an economics professor at Princeton University. "Especially the deficit, inequality, health care, and infrastructure investment."

President Donald Trump promised everyday Americans a "giant tax cut for Christmas" in a speech at the White House.

If the tax changes end up helping markets most, they'll be widening a gap noted last month by JPMorgan Chase's chief investment strategist, Jan Loeys. There's not much sign of "economic overheating," which happens when companies start spending more on wages and other inputs, Loeys argued. "Financial overheating, in contrast, is well advanced," he wrote. "It merits monitoring a lot more closely for signs of bubble-trouble."

Even Trump's Treasury has flagged the danger. Last week, the Office of Financial Research made its annual report to Congress on the vulnerabilities of the financial system. It was sanguine about most of them, from inflation and bank solvency to debt levels.

But the agency, which color-codes its assessments, did see one major threat -- from market risk. That gauge is at red alert.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Our current political moment

Our current political moment