Contrary to what many of us were taught in Introduction to Economics courses in college and graduate school, markets are rarely perfectly competitive. In the case of the market for labor—a market that, it is worth noting, is fundamentally different from those where financial products or commodities are bought and sold—imperfect competition means that workers' pay is solely determined neither by their productivity nor by the forces of supply and demand.

In recent years, rising interest in the causes, consequences, and policy implications of imperfect competition has sparked a new wave of research on a framework known in economics as monopsony. Kate Bahn, the director of labor market policy and chief economist at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, defined monopsony in a briefing to congressional staffers last month: "Monopsony can be narrowly defined as any time there is one or few employers hiring workers, so they have considerable power to keep wages low since those workers do not have a lot of other options for jobs."

But monopsony power, Bahn noted, is present not just when there are only a few employers in a particular labor market. Barriers that limit workers' ability to move from job to job, incomplete or asymmetrical information about jobs, and discrimination are all factors that can give employers an upper hand when setting wages and, with it, the power to underpay workers.

Hosted by Equitable Growth on March 23, the briefing, part of a series dubbed "Econ 101," introduced Hill staffers to labor markets under monopsony. During the presentation, Bahn first discussed how the assumptions that underpin the view that markets are perfectly competitive are rarely met. She then described the basics of the monopsony model and covered some of the empirical evidence on how monopsony affects the U.S. workforce and economy. And to wrap up, Bahn discussed the public policies that can counteract employers' wage-setting power, boost competition, and deliver broadly shared economic growth.

The implications of monopsony for U.S. labor markets

So, what are the implications of monopsony for our understanding of how labor markets work? And what does imperfect competition mean for the design of effective and equitable economic policy?

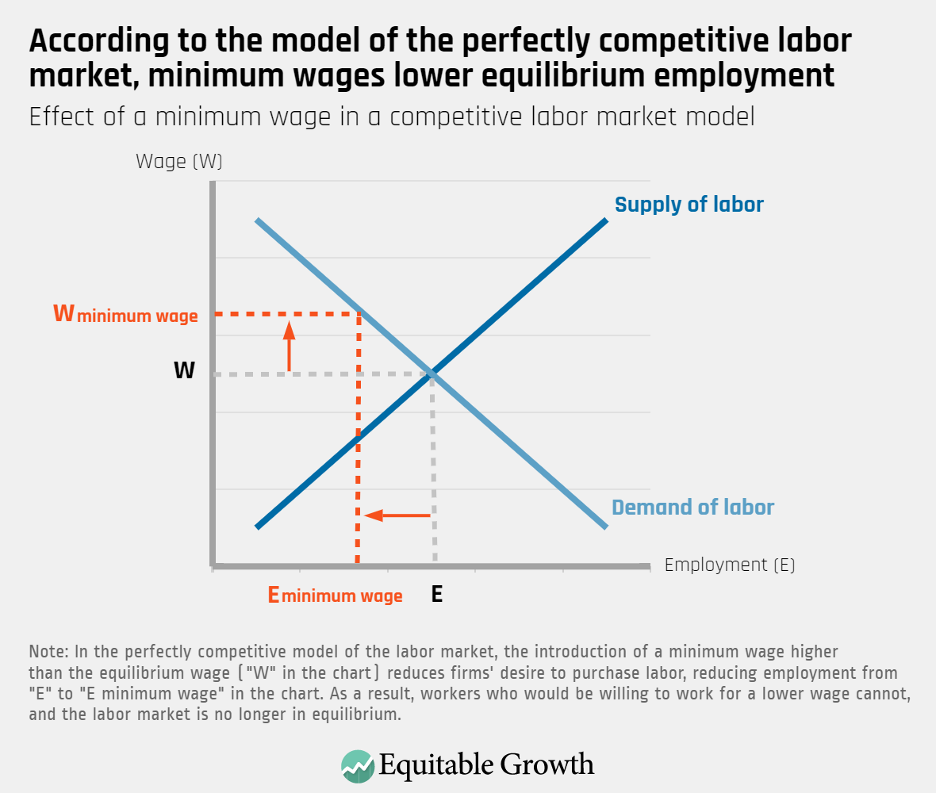

Consider the basic supply-and-demand model of the labor market. According to this framework, when governments enact a wage floor, they artificially set wages at a level that reduces firms' desire to hire workers. As demand moves away from equilibrium and up along the labor demand curve, people who would be willing to sell their labor at a "competitive" wage (the theoretical market rate) are unable to find work. In this hypothetical labor market, then, firms hire fewer workers than they want to, workers who would like to sell their labor cannot, and employment is lower than it would be under equilibrium. In economic terms, wage floors lead to socially inefficient outcomes. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Further, under this model of perfect competition, employers are "price-takers," meaning that they must accept the market wage and have no way of influencing it. The assumptions that underpin the perfectly competitive model of the labor market—for instance, that all market participants have perfect information, that all workers are able to seamlessly transition from job to job, and that wages are an accurate reflection of all workers' productivity—also imply that workers are very sensitive to wages. In other words, an employer only needs to pay one cent more than its competitors to have an unlimited supply of workers.

At last month's event, Bahn noted, however, that "if workers face frictions when trying to find a job—if workers do not know what jobs are available or face constraints in what kind of position they can take—then employers do not need to only pay one cent more than their competitors to have an unlimited flow of workers."

Indeed, researchers document that various obstacles when trying to land a position, the concentration of a few employers in any given labor market, and employee preferences about job characteristics besides wages make workers much less sensitive to pay than the perfectly competitive model proposes. "In the actual labor market, employers do not have to offer pay raises or cost of living adjustments tied to inflation if they do not have to compete for workers," Bahn told congressional staff.

In addition, empirical evidence shows that these noncompetitive forces affect U.S. labor market dynamics, with monopsony power giving employers the ability to pay wages below workers' productivity. For instance, a team of economists at the University of California, Los Angeles, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Burning Glass Technologies shows that more than 10 percent of the country's workforce is in labor markets where lack of outside options for their current jobs leads to employer concentration, depressing these workers' wages by at least 2 percent.

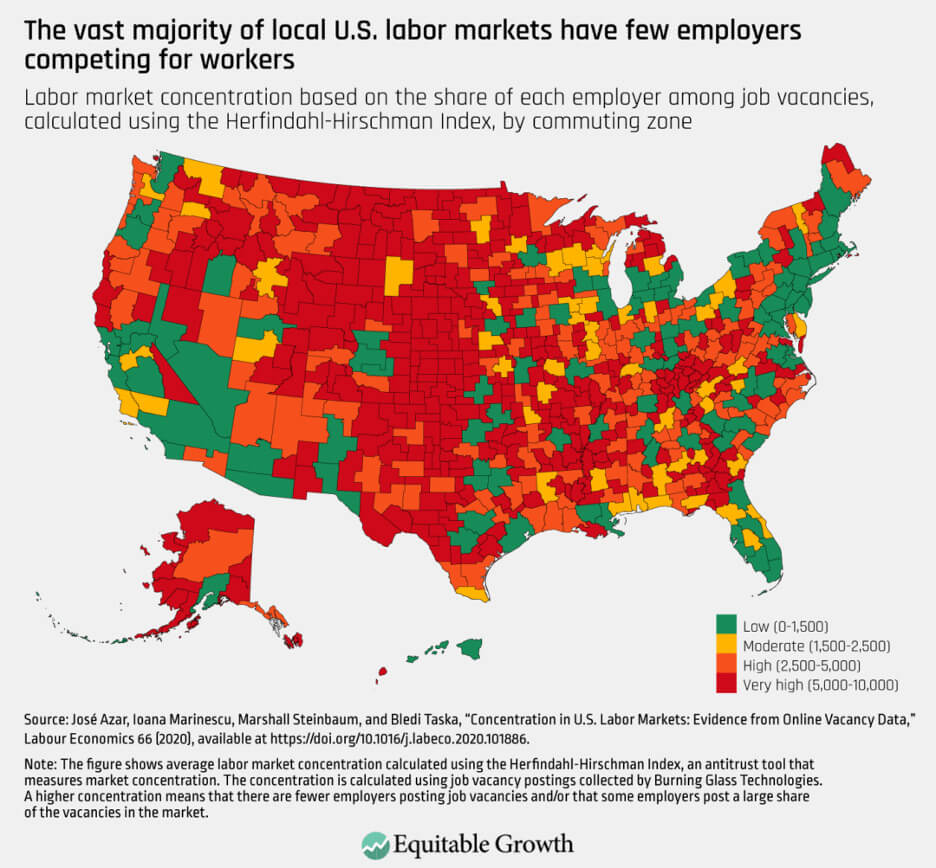

In other words, in parts of the country where relatively few employers are competing to hire, lack of competition pushes down average pay. Highly concentrated labor markets, another study finds, are especially pervasive in rural and less densely populated areas. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Other studies highlight how one big employer can influence marketwide wages. For instance, research by economist Ellora Derenoncourt (now at Princeton University) and Clemens Noelke and David Weil at Brandeis University shows that as Amazon.com Inc. set a $15 minimum wage in late 2018, other employers in the same commuting zone had to increase wages. Amazon and other big and powerful employers, the authors find, can therefore act as a wage-setters rather than price-takers, pushing wages up or dragging them down depending on what their particular corporate policy is at a given time.

A study examining how the opening of Walmart Supercenters affects local labor markets captures how one firm's monopsony power leads to worse labor market outcomes. The research finds that Supercenters lead to a decline in countywide employment and earnings as Walmart undercuts wages through low-road employment practices that spill over on other local workers and industries—a dynamic that was mitigated in the counties that experienced an increase in the minimum wage and that would not take place under perfect competition.

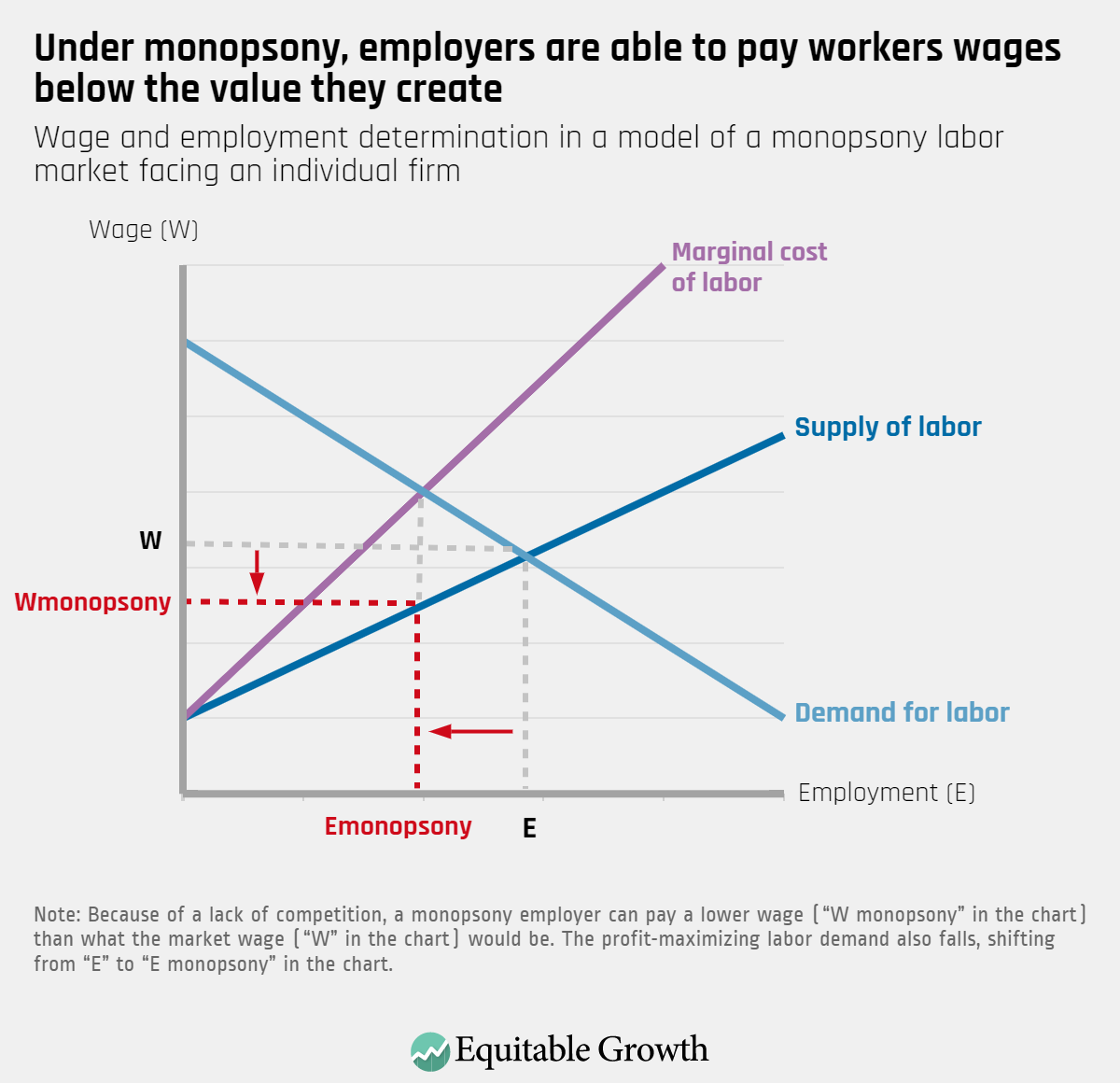

So, how does our model of the labor market change when we assume imperfect competition? Under monopsony, the labor demand curve and labor supply curve intersect at both a lower wage and at a lower employment level than would be achieved under equilibrium. This results in socially inefficient outcomes, where the lost wages due to underpayment are kept as firms' profits, with workers making less than the value they contribute. Contrary to the perfectly competitive model of the labor market, in this model, higher wages also lead to greater equilibrium employment. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

In contrast to Figure 3 above, in a competitive labor market, if a firm tried to pay only "W monopsony" wages, then workers would go to other firms willing to pay a higher wage.

How policymakers can protect workers from monopsony power in the U.S. labor market

There are two broad areas of public policies that can counteract these forces and create greater balance between the power of employers and the power of workers: pro-competition policies and pro-worker policies.

To boost competition in labor markets, policymakers can start by banning noncompete agreements—contracts that limit workers' ability to move from job to job and that affect a large share of low-wage workers. Public policy also should support workers' bargaining power by raising the federal minimum wage, expanding the right to organize and join a labor union, and enforcing labor standards to prevent violations, such as wage theft and employment discrimination.

Together, these policies will boost wages and increase job quality, increase competition and productivity, and drive broad-based economic growth.

To learn more about how monopsony affects the U.S. labor market, see the presentation slides from the March 23 congressional briefing here. For a write-up of a previous "Econ 101" briefing, on the effects of federal tax changes, see here.

The post Understanding the economics of monopsony: How labor markets work under imperfect competition appeared first on Equitable Growth.