https://www.peoplesworld.org/article/amazon-wont-let-us-leave-tornado-creates-modern-triangle-shirtwaist-factory/

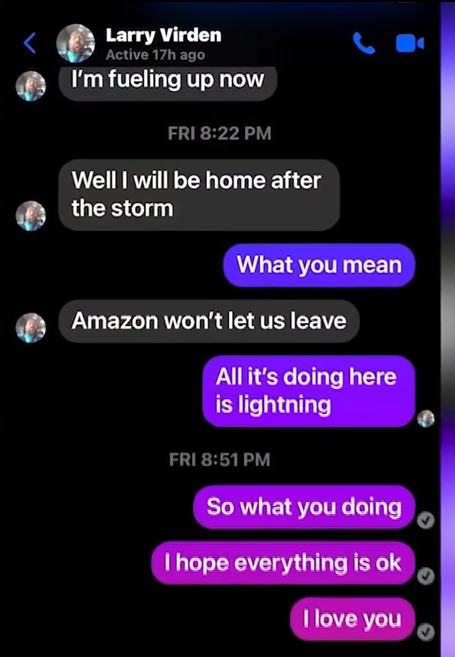

"Amazon won't let us leave." That was the last message 46-year-old Larry Virden sent his girlfriend on the evening of Dec. 10. A short time later, a tornado blasted through Edwardsville, Illinois, and shredded the Amazon fulfillment center warehouse where Virden worked. When the roof of the massive facility came crashing down, he and five co-workers were left dead. Cherie Jones, his partner of 13 years, is now in mourning and explaining to their four children why dad is never coming home.

According to Jones, Virden could have gotten back in time to shelter with his family—if only his employer hadn't ordered workers to stay at the facility. Amazon claims supervisors moved to get as many workers as possible to designated safe spots in the warehouse, but Virden's final text is a rallying cry against the willful anti-worker negligence of the retail behemoth.

Amazon wasn't the only corporation implicated in tornado-linked worker deaths that night, though. Eight more were killed at the Mayfield Consumer Products Company's candle factory in Mayfield, Ky. There, too, workers wanted to flee an approaching twister, but bosses reportedly told them they'd be fired if they left the plant. The damage in Mayfield was even more devastating than that in Edwardsville; all that's left of the candle factory is a pile of rubble.

The two sites—which are essentially crime scenes—invite comparisons to the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911. There, 146 garment workers—123 women and girls and 23 men, many of them Italian and Jewish immigrants—were killed when flames engulfed a high-rise clothing plant in New York City's Greenwich Village. Many were burned alive, others suffocated from the smoke, while dozens more desperately jumped or fell from windows.

The Triangle company had chained the doors of the factory closed, a common practice among bosses at the time in order to keep workers from taking breaks or leaving before managers said they could.

Immediately after the tragedy, socialist leader Rose Schneiderman told the members of the Women's Trade Union League: "I would be a traitor to those poor burned bodies if I came here to talk good fellowship…. Too much blood has been spilled…. It is up to the working people to save themselves. The only way they can do that is with a strong working-class movement."

A wave of worker organizing and agitation for workplace safety was sparked by the blaze. Survivors of the fire became major advocates for unions as the only way workers might collectively protect themselves from corporate greed. Fire eyewitness Frances Perkins took up the investigation for the state and was instrumental in putting safety front and center; later she would be the United States' first woman Secretary of Labor under FDR and said the Triangle fire was "the day the New Deal was born."

From the ashes arose the country's first laws mandating fire safety and improved building codes, regulations for working conditions, improved sanitary facilities, limiting of working hours for women and children, and official encouragement for collective bargaining. Everything from minimum wage laws to workers' compensation to the creation of OSHA can be traced back to the long reform drive that followed the disaster. Triangle became a turning point in the struggle to save workers from being literally killed for the sake of profits.

It was chains on doors that condemned people to death in the Triangle fire 110 years ago; orders from supervisors and threats of termination achieved the same outcome in Edwardsville and Mayfield this week. Now, just like then, corporations treat workers like they are disposable.

Amazon's disaster in Illinois is not unique; it is the latest episode in a long-running tragedy. One worker who spoke to People's World, recounting how Amazon kept its New York warehouses operating even during deadly flooding recently, said, "They legitimately don't care if we die. Their profits don't suffer." People's lives are being put on the line needlessly, but corporations and the billionaires who own and run them refuse to take responsibility.

The Amazon workers who are involved with the Amazon Labor Union are taking up the challenge of stopping things like this from happening again. For the employees in its fulfillment centers, Amazon dictates every aspect of their work life—pay, benefits, working conditions, safety measures, access to telephones. The workers have no power to negotiate any of these things, even though it's their labor power which rakes in the billions for Jeff Bezos and the company's other owners.

Amazon, the union says, consistently values its profits over the people who work there. The deaths of workers like Larry Virden in Edwardsville, who were ordered to stay at work even as a deadly storm approached, are proof of that.

Workers in Amazon—and at companies like Mayfield—need unions because a union is the only way that workers can collectively leverage their power to force change. Amazon and other corporations know this, which is why they spend so much effort trying to convince employees not to join up with the union and fire workers who try to organize. And bought-and-paid-for politicians in right-to-work states like Kentucky know it too, which is why they keep anti-union laws on the books.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

No comments:

Post a Comment