I recently came across a paper by Ursina Schaede and Ville Mankki that contains a fascinating empirical finding with major implications for the way in which we think about meritocracy.

The paper examines the long run effects on students of a change in the manner in which their teachers were selected into a graduate program. Finland is well known for having an extremely effective school system, in part because primary teacher education has been "exclusively taught as a research-oriented, five year masters' degree at universities" since the 1970s. These programs are in very high demand among applicants, with acceptance rates of about 10 percent. The admissions process has a first stage based largely on scores on a high school matriculation exam, followed by a second stage involving interviews and the evaluation of live teaching. Candidates are ranked again at the end of the process, and those at the top are taken until capacity is filled.

For a number of years, acceptance into the second stage was based on a quota, ensuring that at least 40 percent of students making it through the first stage of evaluation were male. Although this did not place any constraint on second stage outcomes, it turned out that the entering classes (and hence several cohorts of trained teachers) did not differ much in gender composition from those making it through the first stage. The quota was abolished in 1989, leaving first stage outcomes unconstrained. The first post-quota cohort thus graduated in 1994.

The paper examines the causal effects of this change on the long run outcomes for students. Identification is facilitated by variations across municipalities in the age distribution of teachers at the time of quota removal, coupled with mandatory retirement at age 60. This means that students were differentially exposed to the newer post-quota cohorts, which had a different gender composition (fewer males) and a different distribution of scores on the matriculation exam (higher scores on average).

The authors find that students differentially exposed to the quota-constrained cohorts of teachers ended up with better educational attainment and labor force participation at age 25. In other words, removal of the quota led to a decline in student performance. While this finding is interesting in its own right, even more interesting are the mechanisms that the authors rule out, and the one that they eventually accept.

Could the effect be arising through a role model channel, with particular benefit for boys? No, the authors find "no evidence for boys' educational attainment being more affected from exposure to male quota teachers relative to girls," and none of their "main effects differ systematically or significantly by pupil gender."

Could it be that male and female teachers bring different benefits to the table, with the whole being greater than the sum of its parts? This would be a benefit from diversity. The authors cannot rule this out entirely (the estimates are too noisy) but they do find that "the benefits of adding an additional male teacher are similar in magnitude between places with few male teachers and places where the share of men among colleagues is already high."

What, then, do the authors think is driving their results? They argue that the evidence "is consistent with male quota teachers contributing positive qualities to the school environment that are not sufficiently captured by the selection criterion in absence of the quota."

It is important to be clear about this, because the finding can be so easily misunderstood. It is not that the quota teachers proved effective because they were male. It is that the distributions of important characteristics (unmeasured by scores) were not identical across male and female applicant pools. The quota was picking up individuals with these characteristics by proxy. It is the characteristics that mattered for students, not the gender of the teacher.

For example, male teachers in the data were "slightly more likely to come from rural areas and to live in their region and municipality of birth when compared to female teachers." So a quota that favored rural applicants or those who had not moved from their municipality of birth could have had similar effects. In fact, this helps explain the mechanism—if rural applicants have fewer resources on average, they will have higher ability conditional on any given score than applicants from more resource-rich urban environments.

In fact, it is extremely likely that even within a given applicant group (men or women), the conditional distribution of these other valuable characteristics is not independent of score. There may be a particular range of scores at which these other characteristics happen to be especially abundant. In this case a policy that optimizes benefits for students may not even be monotonic within group—some people with higher scores would be skipped over in favor of those with somewhat lower scores.

This possibility is discussed at length in a recent paper with Rohini Somanathan that I will present at a symposium at Yale next week. The event has been organized by Gerald Jaynes and Rohini Pande, and is open to all (with registration).

Of course, policies that are non-monotonic (within group) would give rise to incentive effects, and probably could not be sustained. But the conceptual point they raise is that the understanding of meritocracy in public discourse is terribly impoverished. If one were to design a truly meritocratic policy, it could well have features that resemble the pursuit of representation targets. Meritocratic policies will not, in general, involve the application of a common score threshold across all candidates.

I understand that Ursina is on the academic job market this year and that this is the paper she'll be presenting. I think that the work will be influential, and I wish her luck.

Subscribe to Imperfect Information

On economics, identity, justice, and discourse...

NEW DELHI – The World Inequality Report 2022, produced by the Paris-based World Inequality Lab, is a remarkable document for many reasons – starting with its demonstration of the immense power of patient collective research.

3Add to Bookmarks

PreviousNext

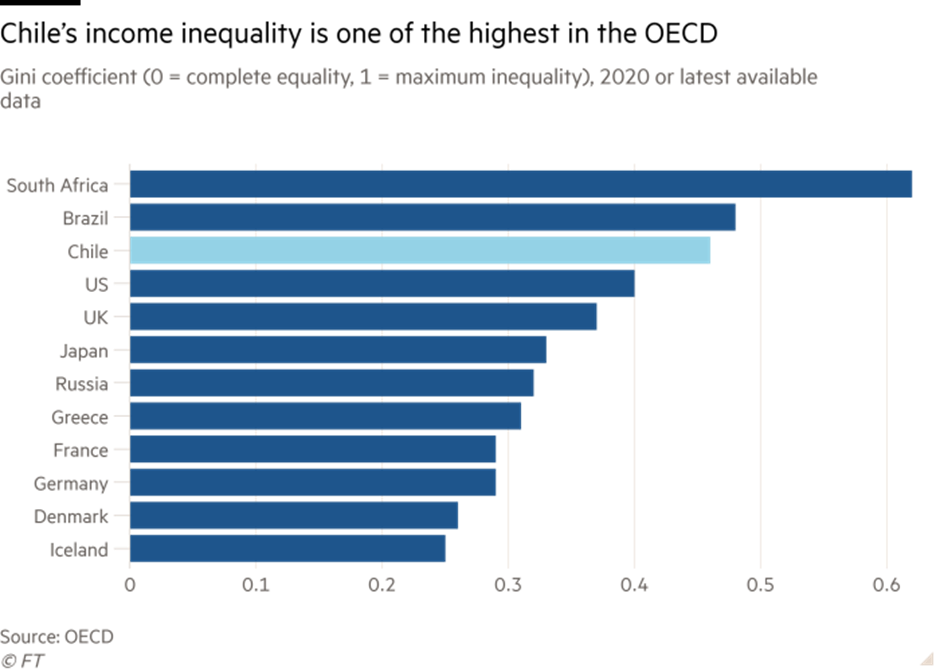

The report provides the latest estimates, based on careful aggregation of national data from a multitude of sources, of income and wealth inequality at the national, regional, and global level. It gives long-run time-series data for these indicators, allowing us to consider recent patterns in a broader historical context. And it expands on different dimensions of inequality in revealing new ways.

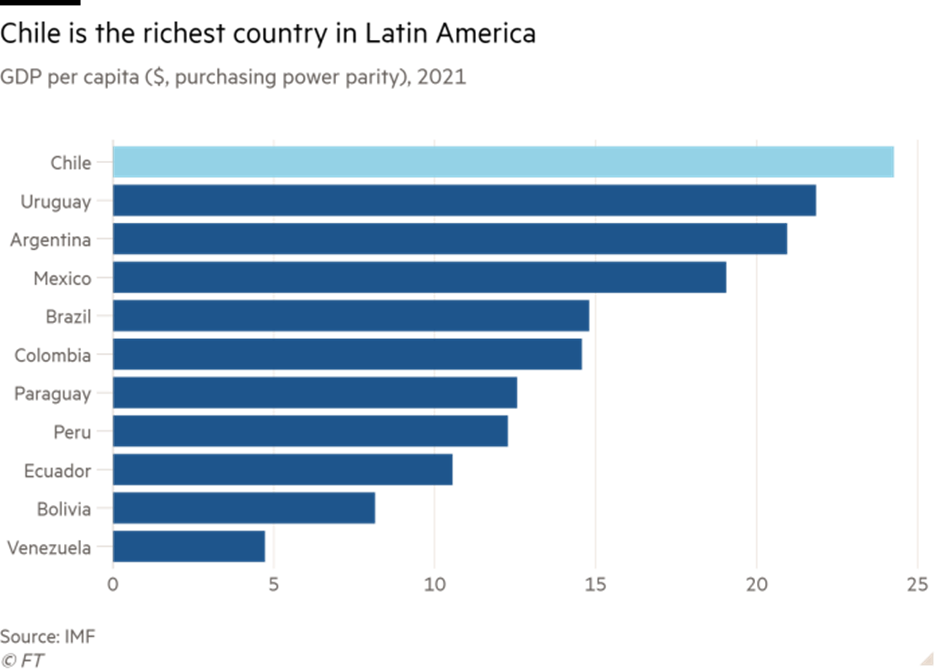

Any research enterprise as ambitious as this one will inevitably elicit quibbles about the datasets used, the assumptions required to generate particular series, and the ways in which some data gaps have been filled. My own minor criticism relates to the World Inequality Lab's use of purchasing power parity (PPP) exchange rates to determine and compare national incomes across countries.

As I have argued elsewhere, while PPP exchange rates appear to control for cross-country differences in price levels and living standards, they are ridden with conceptual, methodological, and empirical problems. For starters, PPP exchange rates assume that the structure of each country's economy is similar to that of the benchmark country (the United States) and changes in the same way over time. When applied to developing economies, this assumption is especially weak.

Moreover, the convoluted weighting procedure for goods can result in the inclusion of unrepresentative, high-priced products that are rarely consumed in some countries. For example, Angus Deaton has noted how packaged cornflakes may be available in poor countries but are bought by only a relatively small minority of rich people. Expenditure weights from national accounts do not reflect the consumption patterns of people who are poor by global standards.

There is a further, and possibly even more troubling, conceptual issue. High-PPP countries – that is, those where the actual purchasing power of the local currency is deemed to be much higher than its nominal value – are typically low-income economies with low average wages. PPP is high precisely because a significant section of the workforce receives very low remuneration, which means that goods and services are available more cheaply than in countries where the majority of workers receive higher wages. The widespread incidence of unpaid labor in many poor households in low-income countries further amplifies the effect. So, it is clear that the local currency's greater purchasing power reflects conditions of indigence and low or no remuneration for what could even be the majority of workers.

PPP-modified GDP data may therefore miss the point. By regarding greater purchasing power of a given monetary income as an advantage, rather than a reflection of the greater absolute poverty of the majority of an economy's workers, PPP estimates effectively overstate poorer countries' incomes compared to those of rich economies.

For all these reasons, relying on PPP exchange rates in cross-country income comparisons – including for poverty and inequality measures – is extremely problematic. There is a strong case for sticking to market exchange rates in measuring cross-country inequality, which would likely reveal much greater disparities than those evident in the World Inequality Report.1

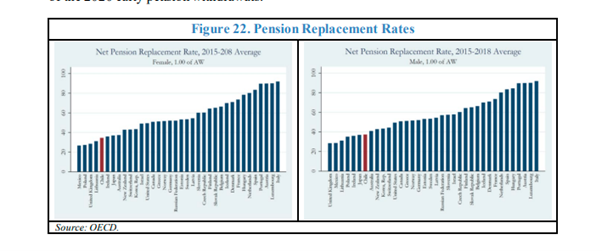

This objection notwithstanding, the report adds much to our understanding of inequality, especially through two new measures. The first is the female share of labor income, which is a useful indicator of gender inequality. Globally, this share has remained largely unchanged over the past three decades, at one-third, and has been as low as 10-15% in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) and below 20% in Asia excluding China. This indicator captures not just labor-market imbalances, but also, implicitly, the greater proportion of unpaid work performed by women within households and communities, which reduces their access to paid work and affects their remuneration in paid employment.

The second innovative measure examines inequality in carbon-dioxide emissions by assessing contributions by income category across countries. The important finding here is that, while inequalities in emissions across regions are high and persistent, such disparities exist not only between rich and poor countries, but within them. There are high emitters among the rich in low- and middle-income countries, and relatively low emitters among the poor in high-income countries.

For example, the richest 10% of people in the MENA region emit 33.6 tons of CO2 per person per year, compared to less than ten tons among the bottom half of the income distribution in North America. (The bottom 50% in Sub-Saharan Africa emit one-twentieth of the North American amount, or 0.5 tons per capita per year.)1

Globally, the richest 10% of the population is responsible for more than half of all CO2 emissions. This point is especially important because, as the report notes, environmental policies like carbon taxes hit the poor the hardest, but this group is rarely if ever compensated for such measures. The new indicator enables a much richer consideration of what socially just climate policies should look like, both within and across countries.

Predictably, the report is strong on appropriate redistributive policies, especially the potential for increased taxation of wealth and corporate profits. There is also scope for looking more closely at "predistribution," or the range of regulatory regimes and legal codes that have enabled today's excessive concentration of wealth and income in the first place.

The primary cause of "predistributive" inequality is, in a word, privatization: of finance, the natural commons, the knowledge commons (through intellectual-property rights), and public services and amenities. One could add to that states' tendency – glaringly obvious since the 2008 global financial crisis – to protect large-scale private capital, while allowing it to wreak havoc on ordinary citizens.

The reality captured by the World Inequality Report reflects human choices, which means that it can be changed by making other choices. That is why the report is much more than a valuable compendium of useful data and analysis. It is a guide to action.