https://equitablegrowth.org/the-coronavirus-recession-continues-to-threaten-low-wage-u-s-workers-due-to-stalled-jobs-recovery/

Today's U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Jobs Report demonstrates a stalled jobs recovery following the deep and rapid economic decline brought about by the coronavirus pandemic. The unemployment rate has decreased slightly to 6.7 percent, but still remains higher than the 3.5 percent unemployment rate in February prior to the start of the coronavirus recession.

The workers who have been hit the hardest continue to be Black workers (10.3 percent), and Latinx workers (8.4 percent). Women workers saw a decrease in unemployment (6.1 percent) that was accompanied by a slight decline in labor force participation (57.1 percent). These workers are also disproportionately low-wage workers as the service sector industries in which most of these workers are employed are among the hardest hit. To put this in context, when the deepest effects of the pandemic hit the economy in April, the unemployment rate reached a post-World War era high of 14.7 percent and the prime-age employment-to-population ratio plummeted to 69.7 percent—a 10 percentage point drop from the previous month.

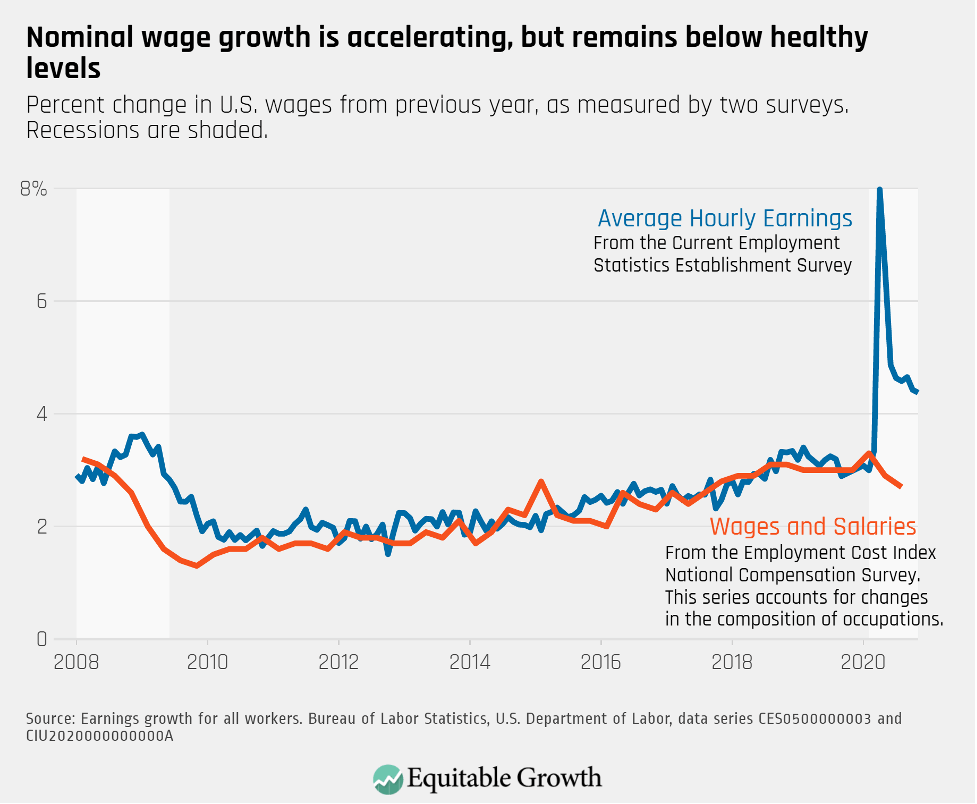

The same month, however, one important economic indicator pointed to another direction. Seemingly contradicting one of the main laws of economic theory, just as labor demand plummeted—when economists would expect wages to decline in tandem—average hourly earnings jumped 8 percent in April relative to the same month of 2019. This massive rate of growth is not even observed during booms: Using this same measure, average wage growth did not surpass 3.8 percent at any point during the 2009–2020 economic expansion. This month wage growth normalized somewhat, with an average worker in the private sector earning $29.58 $an hour, a 4.19 percent increase from the year before.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics provides a disclaimer in the Employment Situation Summary that "the large employment fluctuations over the past several months—especially in industries with lower-paid workers–complicate the analysis of recent trends in average hourly earnings." While higher-wage workers are more likely to be able to telecommute during the current public health crisis, low-wage workers are more likely to lose their jobs. The coronavirus recession has led to a unique contraction of the service sector, changing the composition of employment in the overall U.S. labor market.

As research by Peter Ganong at the University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy and Pascal Noel and Joe Vavra at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business shows, unemployment this year is greater for low-income workers. They estimate that workers' whose pre-job loss weekly earnings put them in the bottom 20 percent of earnings distribution were experiencing a jobless rate of 16 percent between April and July of 2020. Those in the top 20 percent of the income ladder, by contrast, were experiencing an unemployment rate below 4 percent.

As lower-income workers disproportionately lost their jobs, higher-earning workers were more likely to remain employed, which taken together mechanically increases average earnings. Similarly, research by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco shows that in these first months of the coronavirus recession, workers in the bottom quartile of the earnings distribution represented about 1 in 2 of all transitions out of employment.

When looking at other metrics of wage growth, another picture emerges. Accounting for changes in the composition of occupations by measuring wage and salary growth for a fixed set of jobs, the Employment Compensation Index of the National Compensation Survey shows that rather than accelerating, wage growth has slowed down. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

At the onset of the pandemic there was some expectations that the earnings of essential and front-line workers would rise. According to the hypothetical premise of "compensating wage differentials" in labor economics, employers need to make more attractive offers in order to convince workers to do risky or undesirable jobs. In the early months of the health and economic crises, there was some evidence that this would be the case. Companies such as Amazon.com Inc., Costco Wholesale Corp, and Walmart Inc. offered front-line and essential workers—cashiers, warehouse, and fast-food workers, for example—hazard pay, bonuses, and sick paid leave.

That is largely no longer the case. Many workers on the front lines and concerned about getting sick are no longer receiving extra compensation. According to a poll commissioned by the Economic Policy Institute, in mid-May only about 30 percent of respondents working outside from home were receiving some kind of hazard pay, even as more than 50 percent were concerned about contracting the coronavirus and falling ill from COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus. Throughout the late summer and fall, even as the health crisis continued to put workers at risk, many businesses cut those benefits.

As the public health crisis worsens, states are maintaining partial opening or strengthening so-called lockdowns to limit the surge of the pandemic. Economist Trevon Logan at The Ohio State University estimates that hour reductions during peak hours for bars after 10 p.m. as well as limited capacity requirements in restaurants and bars are translating into at least a 50 percent wage cut for many service workers.

It's important for economists and policymakers alike to consider where the U.S. labor market is today compared to prior to the pandemic. Back then, wage growth had finally started to ramp-up for the first time in years. As many states and cities increased their minimum wage and the labor market tightened, wage growth accelerated the most for the lowest earners, yet significant income inequality and differences in unemployment rates by race remained persistent. Now, after the coronavirus recession caused an unprecedented number of jobs lost and widespread pay cuts, elevated unemployment rates will likely exert downward pressure on wages as workers find fewer jobs options and grow increasingly desperate as unemployment benefits expire.

This is why it's essential to put forward policies that help maintain labor standards, including increasing earnings through minimum wage increases and ensuring workplace safety amid the pandemic so that an eventual recovery is robust and resilient, rather than further entrenching economic inequality. Recent research and today's Job Report further emphasizes the need to center economic policies around the well-being of the hardest hit workers to ensure they won't have to wait another 10 years for strong wage growth.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

No comments:

Post a Comment