https://ritholtz.com/2019/06/amazon-bomb-may-31-1999/

Amazon.Bomb (May 31, 1999)

Looking Back at a Bearish Call on Amazon

Twenty years ago, how could Barron's or anyone else know what would become of an internet bookseller?

Bloomberg, May 31, 2019

So often, it is difficult to distinguish the things we think we know from those we have no idea about. An especially vivid illustration of this is a column published 20 years ago this weekend in Barron's about Amazon.com. "Amazon.bomb" reveals not only the state of the dot-com bubble and how far markets were off their leash in on May 31, 1999, but the eternal truth that it is impossible to see into the future.

At the time, Barron's, alarmed at how far company valuations had risen, was warning about market risks, especially in the technology sector. In this, the editors were early, but they would be proved correct.

The Amazon column, in many ways an excellent article, focused on one of the sector's highest flyers:

"But since early May, a lot of investors have been learning that a good story does not always make a good stock. From an April high of 221 1/4, Amazon shares have been sliced nearly in half, to 118 3/4, cutting the company's worth to about $19 billion and reducing Bezos' fortune to $7 billion. The stock could fall a lot further. Remember, adjusted for stock splits, these shares were worth just $3 apiece when they were first issued to the public two years ago. Several analyses, including two in this magazine, have indicated that the shares could be worth less than $10 apiece."

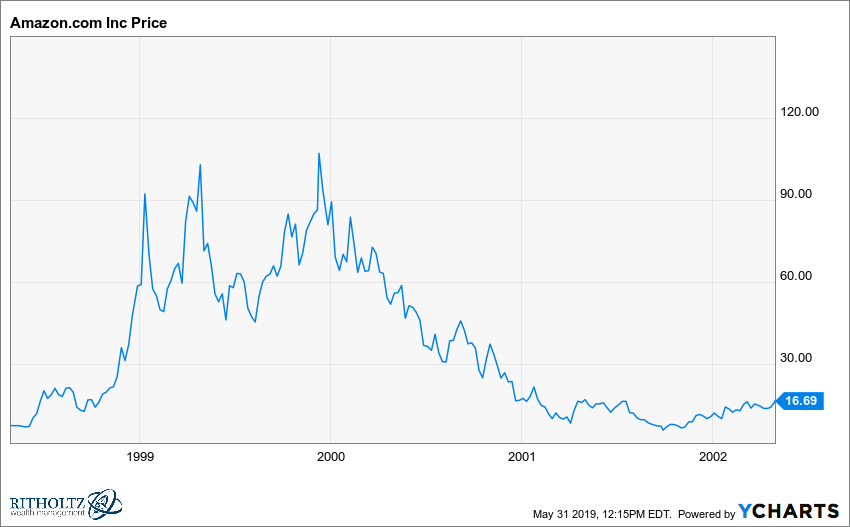

Let's unpack all the delicious history in this paragraph. For one thing, it contains a prescient warning of an impending collapse in the stock price (and the entire tech sector). If you took the discussion in the column to heart and sold Amazon, you did very well: Over the next few years, Amazon's stock would drop 95 percent, eventually falling to below $6 in 2001 from over $100:

Missing a 95% Collapse over the next 2 years

At the same time, it reminds us how differently things can look in the short term — when bearish can be the right trading call — than they do over the course of many years — when the preferred posture is bullish.

Consider Amazon's annual revenue: In 1998, the company posted a loss of $125 million on revenues of $610 million. From today's perspective, those numbers seem almost shockingly low. Amazon's daily revenues are now greater than the company's annual revenues were in 1998. Last year, the company sold $241.5 billion worth of goods and services — $ 661.6 million per day about $50 million more per day than the company sold in all of 1998. Even adjusted for inflation, 1998 revenues are less than $1 billion for the entire year.

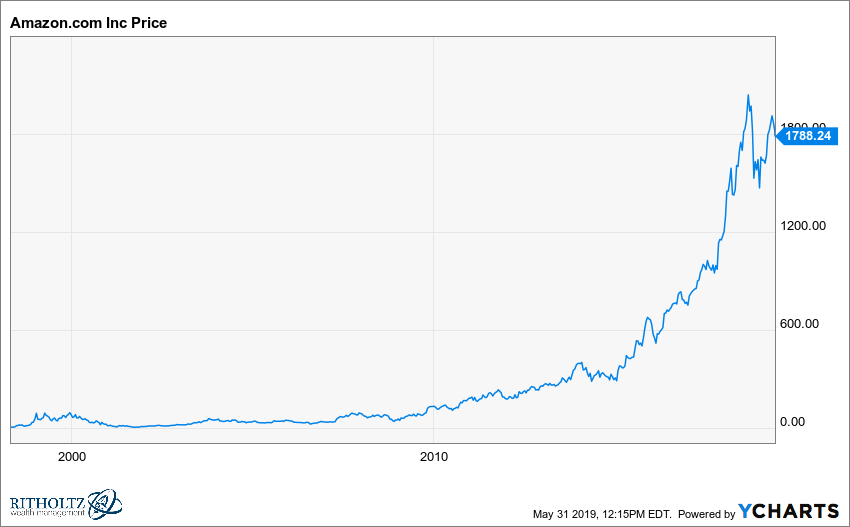

Look, too, at the market capitalization of Amazon prior to that 95 percent collapse. Anyone would love to travel back in time to buy Amazon at a mere $19 billion valuation and watch that multiply 47 times to $894.2 billion. My back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest Amazon has risen 4,606% since Barron's published its column, with an annualized average return of 21.1% — about quadruple what the S&P 500 returned over the same period.

Not too shabby.

But there is yet another historical lesson here. Anytime some company is said to be "the next Amazon" (or Apple or Microsoft), keep in mind that most people would be unable to withstand the sort of pain and wealth destruction that goes along with investing early, even if the ups and downs are temporary. Only if investors can withstand the subsequent drawdowns — in Amazon's case, 83% in 2000; 73% in 2001; 41% in 2004; 46% in 2006; 64% in 2008 — will they be amply rewarded.

The Subsequent 4,606% move

And while the reversals are happening, investors have no idea whether they will be temporary. In real time, it feels like nothing short of an unmitigated disaster. Oh, and if the stock is Enron or Lehman Brothers or any one of the thousands of companies that have gone bankrupt, then fear is justified. There's simply no way to know at the time whether or not $AMZN is going to turn out to be "Amazon", or whether the meek finance geek Jeff Bezos is going to become Bezos Prime.

Well considered as it was, the Barron's column got lots of fundamental things wrong: Authors would not end up selling their own books from their own websites. High-profile publishing houses would not take the market away from Amazon. My favorite quote in the column comes from retail consultant Kurt Barnard, who said: "Once Wal-Mart decides to go after Amazon, there's no contest. Wal-Mart has resources Amazon can't even dream about." Well, he was half right: It was no contest.

But in 1999, no one could predict that Amazon would expand far beyond books; create Kindle, Echo and other devices; build out a multi-billion-dollar cloud business; create original television and movie programming; develop Amazon Prime, which would penetrate 60% of U.S. households (with greater concentration among the wealthy); become the third most valuable company in the world, briefly touching a trillion-dollar market cap; and capture nearly half of all dollars spent online.

As William Goldman said about Hollywood: "Nobody knows anything." Something to keep in mind when considering the future of any company.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

No comments:

Post a Comment