http://ritholtz.com/2018/08/the-impact-of-higher-temperatures-on-economic-growth/

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Yves here. It's not hard to infer that I'm skeptical about what sound like one-idea remedies to complex problems. While Mondragon is a noteworthy exception, I wonder if many successful cooperatives have 150 people or fewer in them. The reason for fixating on that number is that various studies have found that is largest group you can have where everyone knows each other, and accordingly, an function without a formal hierarchy.

By Esteban Kelly,Executive Director of the US Federation of Worker Cooperatives. He is a founder and core trainer with AORTA, a worker co-op that supports organizations fighting for social justice and a solidarity economy through consulting. He has served on numerous boards including the Democracy At Work Institute and the National Cooperative Business Association (NCBA-CLUSA). Originally published atopenDemocracy

"When I heard about the green economy for the first time, a light bulb went off in my head. We can create businesses and jobs for ourselves." That's how co-op worker-owner Tim Hall explains his initial spark of inspiration. Eventually he joined together with other unemployed Boston residents to found CERO(Cooperative Energy, Recycling, and Organics), an award-winning food waste pickup and diversion service. The name is fitting, since "CERO"—which means "zero" in Spanish—seamlessly blends their zero-waste mission with a green jobs strategy of workforce development among low-skilled workers, especially immigrants and people of color.

Cooperatives provide a sustainable and accountable way of providing goods and services—and they can help to transform our economies before it is too late. They promise a tantalizing future of sustainable social enterprise, community control, worker self-management and workplace democracy that places economic decision-making back into the hands of workers and consumers. Could co-ops dislodge capitalism and loosen its chokehold on what feels like every facet of our lives, or will they themselves become co-opted?

At some point in the last 50 years capitalism corralled the power to define everything about how we think about economics. That's one of the benefits baked into being the dominant organizing force of the economy. But the bigger truth is that 'the economy' includes more than the profit-maximizing ethos of capitalism, just as 'democracy' isn't the property of Congress or parliament. In democratic societies (at least in theory) we have elected and accountable representatives for everything from parent-teacher associations and children's sports leagues to the general assemblies where members deliberate with each other in neighborhood associations and union halls.

The same is true for economics, where undemocratic, shareholder-controlled, profit-obsessed enterprises have come to be equated with the concept of business itself—and especially with commerce, money, mission and productivity. Cooperatives are for-profit businesses which operate in virtually every industry. They undergird global commerce, particularly in agriculture, energy, and local banking via credit unions, but instead of maximizing profits for their investors they are driven primarily by the interests of their members–– who may be producers on a farm, the residents of an apartment complex, the consumers of utilities and retail goods, or the workers in a factory. In co-ops the goal is to get a better price for farmers, more affordable housing for residents, higher-quality goods for consumers, and meaningful, healthy, fair-paying jobs for workers.

Is this inherently anti-capitalist? In a way, yes, because co-ops use capital to put people over profit, which inverts the profit-over-people logic of the current global economy. Worker cooperatives may be the most coherent alternative to capitalism as we know it because they put capital at the service of labor rather than the other way around. Some fall short of this ideal of course, and co-ops don't guarantee social justice by themselves (which is why we still need social movements), but the co-op model inherently prioritizes the good of the many over the benefit of the few.

Generally speaking, the cooperative economy is better described as 'a-capitalist' rather than 'anti-capitalist,' because it can prosper in both market economies and socialist economies like Cuba, which currently has about the same number of worker co-opsas the United States. But in its desperation to legitimize and stabilize itself, capitalism is eager to co-opt at least the superficial characteristics of the cooperative economy, much as it has co-opted sustainable business through greenwashingcampaigns over the last 20 years. Throughout the 20th century we have witnessed capitalism absorb cooperative elements into its structures in an attempt to reconstitute itself during its many crises.

At the same time, it's disappointing but necessary to point out that some of the world's largest cooperatives have managed to compete and survive against conventional businesses by mimicking the corporate cultures of late-capitalist firms. Who knew that American household brands like Land O'Lakesand Ocean Spraywere both cooperatives? And when was the last time you were invited to vote in a general membership meeting of your credit union?

What's more important than being 'pro- 'or 'anti-capitalist' is the recognition that cooperatives must figure heavily in any democratic, post-capitalist economy. This matters a great deal now, because while the contradictions and unsustainable nature of capitalism have become glaringly clear, many people struggle to articulate what will replace it. The exception is a rising consensus that cooperatives (along with small independent and family businesses) will replace the capitalist firm as the core non-governmental form of enterprise in the future. Cooperatives are an essential instrument of economic democracy.

But to succeed in this way, co-ops must stay true to the mission and guiding values. Employee-owned cooperatives force us to confront our own desire to do what it takes to live justly, sustainably, and in a participatory, people-centered way. They remove the excuse that the problem is the demands of the shareholder or the red-tape of government bureaucracy or the bullish will of a boss. When we have worker owned and controlled businesses, we must take responsibility for how well we pay ourselves, how connected our businesses are to the community and its needs, and how healthy our own workloads and quality of life truly are.

For as long as cooperatives fight to persist in a ravenous capitalist economy, these challenges will be greater, because a co-op's products and services must rival the quality and price point of deceitful capitalist enterprises which cut corners on safety and the environment, and steal wages from workers in order to maximize benefits for their shareholders. Cooperatives are put on trial time and again because people want to imbue them with some magical or mechanical power to resolve societal problems. In the current context (or perhaps any context) this is impossible, but they do have the potential to be healthy and restorative as in the case of CERO.

The lowest income people in Boston may be on the frontlines of environmental disaster in their city, but Hall and his colleagues have found a way for their communities to become protagonists in creating solutions. Cooperatives put folks like them at the center of the economy, which means that ordinary people can use the power of business to address their needs and guide how change happens, thus helping to fulfill the promise of a democratic economy—not just voting once or twice a year but coming together to solve problems every day. The real question is this: can we as people put our full weight behind a new economic paradigm that is inclusive, inter-dependent, anti-sexist, multi-racial, anti-imperialist and liberatory?

I've spent 20 years as an active member of many different types of cooperative in the US, including the intimate living spaces of over a dozen shared housing co-ops and handling the day-to-day business of two different worker-run cooperatives. What I can tell you is this: by themselves such co-ops aren't going to save us, nor are they going to transform society. But co-ops are an especially effective tool for change. They leverage innovations from the capitalist era of enterprise and turn them into a positive force within the broader spheres of human relationships, responsible resource consumption, and transparent governance and accountability— typically while staying rooted locally and showing concern for the community.

Deep transformation happens at the level of human beings, who then bring their reorientation to the structures in which they participate. Cooperatives are a vehicle to catalyze that change, but they only yoke together the people in the pilot's seat. What ultimately matters is the disposition of the pilots themselves. We are the ones that have to change.

However, what I've also seen during my decades in cooperative communities is that while co-ops might not transform people, the act of cooperation often does. Not overnight, and not evenly for everyone. But the more my co-workers and housemates participated in cooperative processes like facilities maintenance, financial planning, passing a health inspection or some other shared work or act of problem-solving, the more humility, trust, empathy, stewardship and solidarity we each expressed. The habits of hierarchical, capitalist behaviors receded like the tide as we practiced interdependence and cooperation.

What we need are more opportunities to practice, screw up and improve in this way. And with more practice, we can all develop the qualities required to work through conflict and manage operations sensibly and democratically. Cooperation is the key to a new economy.

This is the most hopeful take on American productivity growth relative stagnation I have seen. I thought it was coherent and might well be right 20 years ago. I think it is coherent and might possibly be right today. But is that just a vain hope?: Michael van Biema and Bruce Greenwald (1997): Managing Our Way to Higher Service-Sector Productivity: "What electricity, railroads, and gasoline power did for the U.S. economy between roughly 1850 and 1970, computer power is widely expected to do for today's information-based service economy...

...But there is increasing concern because improvements in productivity growth are continuing at low levels despite the expenditure of trillions of dollars on information technology. Whereas productivity grew at an annual rate of 3% in the two decades following World War II, it has grown at an annual rate of only about 1% since the beginning of the 1970s. Had the earlier level of productivity growth been sustained, the gross domestic product would now be approximately $11 trillion instead of about $6.5 trillion. That extra $4.5 trillion per year in economic output—which amounts to roughly an additional $18,000 for every man, woman, and child—would be having a profound impact on a wide range of social and economic problems.

What is preventing a productivity revival in the U.S. economy? Clearly, the manufacturing sector cannot be blamed.... Goods-producing activities (such as manufacturing and construction) employed only 19.1% of the labor force in 1992—down from 26.1% in 1979.... Service-producing activities, on the other hand, employed 70% of all U.S. workers in 1992—up from 62.2% in 1979. By 1994, 71.5% of U.S. workers performed service jobs—whether in manufacturing or service organizations—as managers and professionals, salespeople, or technical support staff. Although the service sector's size has grown in the past 20 years, its productivity growth has declined....

Why hasn't productivity grown as fast in the service sector as in the manufacturing sector? Several incomplete explanations have been offered and have resulted, in our view... blame in two places: the ineffectiveness of many U.S. business managers at improving productivity and the inherent complexity of the service sector itself. A management-based approach to improving the service sector's productivity offers hope for a rapid and significant turnaround of the sector's productivity growth rate.... The problem is not a lack of resources; rather, it is that service sector companies operate below their potential and increasingly fail to take advantage of the widely available skills, machines, and technologies. The main reason the service sector has not reached its total potential output is management. If managers were focused energetically and intelligently on putting the existing technologies, labor force, and capital stock to work, rapid productivity growth would follow. To be sure, the management challenges are more severe in the service sector than in the manufacturing sector. However, the high productivity levels attained by leading-edge service companies indicate that attention from management can result in vastly improved performance throughout the service economy...

#shouldreadWhy is the Anthropocene important? And what does our mass media's presentation of the Anthropocene tell us? Professor Emeritus Leslie Sklair shares his research.

There is an enormous amount of research on how 'climate change' and 'global warming' are being reported in the media all over the world. However, since beginning to study the Anthropocene (the geological concept intended to measure and name human impacts on the Earth System) it seems that while some academics, environmental professionals, and creative artists do engage actively with the Anthropocene, most educated and cultured elites do not. It is also becoming increasingly clear that most people in the world have either never heard of it or if they have, they have no clear idea about it. While climate change is important, it only tells part of the story of the threats to our planet and us.

Why is this important?

The simple answer is most scientists researching human impacts on the Earth System believe the Anthropocene presents credible existential threats to the survival of human life on the planet in the foreseeable future. In 2011, Nobel prize-winner Paul Crutzen (a leading populariser of the term) co-authored an article in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society which argued the ultimate drivers of the Anthropocene 'if they continue unabated through this century, may well threaten the viability of contemporary civilization and perhaps even the future existence of Homo sapiens'.

Researching how the Anthropocene is presented in mass media begins to answer my research questions – how likely is it that someone reading the daily news online will come across articles on the Anthropocene, and what will these articles tell them?

The project started in early 2017, and data has been collected from online searches of over 1,000 newspapers, magazines and other media websites from around 100 countries/regions from 2002 (the date of the first recorded articles) to the end of 2017. Media with paywalls and social media were excluded from the study.

The research has come up with some surprising results. Hundreds of Anthropocene articles are actually about events in the creative arts that incorporate Anthropocene references in their titles. When it comes to the science reporting, it is the so-called 'good Anthropocene' that dominates press coverage, kicking the existential threats to human existence into the long grass.

Three very broad messages (Anthropocene Narratives) have been identified from the media searches:

The first two narratives are often difficult to distinguish, and they have been characterised as versions of the 'good Anthropocene'- supported by a variety of think tanks and foundations, arguing that human ingenuity will minimise the risks posed by the Anthropocene in the various eco-systems that constitute the whole Earth System (climate, oceans, forests, soil, biodiversity, etc.). Relatively few articles advocate radical change to the status quo.

A serious appreciation of the potential dangers of the Anthropocene will provide a useful gateway for relatively uninformed publics into a variety of issues that are ignored or misrepresented by the media. It is understandable that both the science and media establishments, and the business and political interests which underpin them, would tend to lean towards reassurance rather than desperation in portraying the perils of the Anthropocene.

However, this is a high-risk situation, probably not for anyone living at present, possibly not even for their grand-children or their great grand-children, but almost certainly for generations to come. Given the continuing failures of governments and international organizations to act decisively, this is a reality that the media and all citizens need to grasp – the issue of human survival is at stake.

An open source article summarising the project to date can be found here.

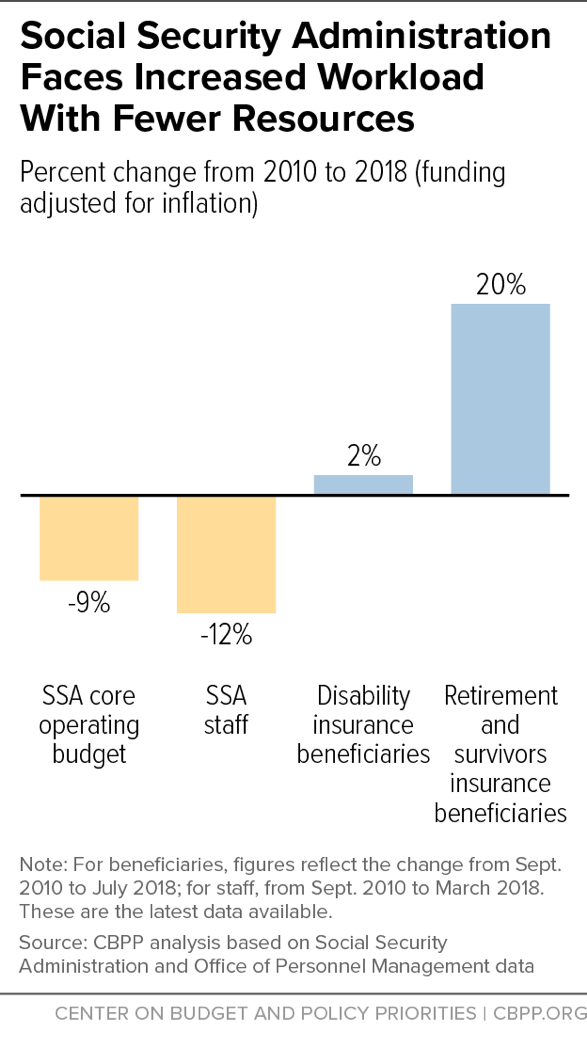

The Social Security Administration (SSA) faces a staffing shortage that hurts hard-working Americans trying to access their earned benefits, but a Senate-passed funding bill wouldn't help — and one that the House Appropriations Committee passed would only make things worse. The House bill would cut SSA's administrative budget by 2.5 percent compared to last year, and the Senate's version would provide a paltry 1 percent increase.

peculation is rising that Chinese President Xi Jinping – possibly accompanied by an honor guard of People's Liberation Army troops – will appear alongside local leader Kim Jong Un at a symbolically important parade in Pyongyang next month.

At a time when Washington has unleashed a trade war upon Beijing, while the denuclearization process agreed between Kim and US President Donald Trump in Singapore at their June summit appears to be stalled, the appearance of the Chinese leader – and elite PLA troops – would send a significant cross-Pacific message about Sino-North Korean amity.Chinese state newspapers including the Global Times and Reference News have run stories this week speculating on the size and significance of the big parade. Typically though, neither the Korean Central News Agency nor Korean Central Television – key media organs in one of the world's most opaque states – have dropped any hints about the upcoming muster of military might.

Posts hinting that President Xi will visit Pyongyang to review troops alongside Kim have not been pulled from social networking platforms by party censors since related rumors started to swirl last month. Nor has talk that Xi may dispatch PLA honor guards to goose-step shoulder-to-shoulder with their North Korean comrades.

While Xi and Kim had never met before this year due to bilateral tensions sparked by Kim's execution of his uncle Jang Song-taek – who had strong connections in Beijing – and by China's support for international sanctions, they have met three times so far in 2018. The meetings proceeded as part of Kim's unprecedented diplomatic offensive, which has also seen him meet Trump once, and South Korean President Moon Jae-in twice.

The friendship between the two avowedly communist states may be in a process of rejuvenation, but is not new. China's intervention in the Korean War saved the North Korean state from extinction at the hands of US-led UN forces in October 1950.

In 1961, the two signed the Sino-North Korean Mutual Aid and Cooperation Friendship Treaty; its second article calls for mutual defense against external enemies. The treaty has been renewed twice and is up for renegotiation in 2021.

The general consensus is that the parade could be considerably larger than one held in February on the anniversary of the Korean People's Army.

Large cavalcades of troops, tanks and artillery on the ground and swarms of war-craft in the air are anticipated, after Kim reportedly ordered the military to put its best foot forward to shore up the morale of North Koreans and cast the image of an invincible army.

The Mirim Parade Training Ground in Pyongyang has been a hive of activity, as seen on satellite imagery taken earlier this month, with around 120 military vehicles in formations, including assault tanks, unmanned-aerial-vehicle launchers and six tarp-covered Scud-class transporter-erector-launchers, among others, captured practicing on the facility's roads.

A replica of Kim Il Sung Square, and an expended tent area believed to house and service troops were also visible in these images.

But the Global Times cited the Stimson Center, a Washington-based think tank, as saying that no launchers for intercontinental ballistic missiles were spotted so far.

Cui Zhiying, director of the Shanghai-based Tongji University Korean Peninsula Research Center, told the tabloid that the Hwasong-15 nuclear warhead-capable ICBMs – with a theoretical range covering almost all of the US – would not be showcased this time for the sake of the thaw in ties between Pyongyang and Washington.

However, those ties, over the last week, appear in danger of freezing over once more, following Trump's order to US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo not to travel to Pyongyang last Friday to attend negotiations. Trump cited a lack of progress in North Korea's denuclearization as the reason for his move.

Xi, assuming he does appear in Pyongyang, will not be the only high-profile visitor in September. Amid an apparent downturn in relations between Pyongyang and Washington, South Korean President Moon has also announced a summit with Kim in the North Korean capital next month.

While there, Moon's key mission will be an intermediary one. He hopes to reinvigorate the denuclearization process and bring Pyongyang and Washington back onto the same page, South Korean presidential officials say.

However, while the dates for Moon's trip have not yet been released, he is highly unlikely to visit on the 9th – the date when the communist state was founded in contravention to his own, US-backed state in 1948.

The 21st Century has not been a good one for most working people in the United States. In fact, for most of this century, real median household income has been below its starting value in January 2000.

The chart below shows real (inflation-adjusted) and nominal (or current dollar) median household income over this century. As we can see, the fall in real median household income over most of the first eight years was nothing compared to the hit median household income took over the next 8 years. This record is even more appalling when one considers that the US was officially in an economic expansion from November 2001 to December 2007, and then again from June 2009 to the present.

The next chart brings the pressures working families have faced this century into sharper relief. It shows the percentage change in real median household income, both monthly and using a three-month moving average, over time. It does this by dividing the value of each median income variable by its respective value at the beginning of 2000.

It has been a long, hard slog, but finally, in 2018, the average household is enjoying some real growth in income. Real median household income, as of March 2018, was 1.8 percent above its January 2000 level. The 3-month moving average was also 1.8 percent above its January 2000 benchmark.

While encouraging, recent gains have been far too small to compensate for the many preceding years of actual loss. Moreover, it remains to be seen how much longer this expansion will continue. As the New York Times reported,

Federal Reserve officials are beginning to worry about a possibility that seems remote to workers who still feel left behind: the danger of the economy's running too hot, destabilizing financial markets and setting off a rapid escalation in wages and prices that could force the central bank to slam the brakes on growth.

Translated, this means that if labor costs rise enough to eat into corporate profits, Federal Reserve officials will respond with interest rate hikes to slow down economic activity and weaken labor's bargaining power. And so goes the new century.

The 21st Century has not been a good one for most working people in the United States. In fact, for most of this century, real median household income has been below its starting value in January 2000.

The chart below shows real (inflation-adjusted) and nominal (or current dollar) median household income over this century. As we can see, the fall in real median household income over most of the first eight years was nothing compared to the hit median household income took over the next 8 years. This record is even more appalling when one considers that the US was officially in an economic expansion from November 2001 to December 2007, and then again from June 2009 to the present.

The next chart brings the pressures working families have faced this century into sharper relief. It shows the percentage change in real median household income, both monthly and using a three-month moving average, over time. It does this by dividing the value of each median income variable by its respective value at the beginning of 2000.

It has been a long, hard slog, but finally, in 2018, the average household is enjoying some real growth in income. Real median household income, as of March 2018, was 1.8 percent above its January 2000 level. The 3-month moving average was also 1.8 percent above its January 2000 benchmark.

While encouraging, recent gains have been far too small to compensate for the many preceding years of actual loss. Moreover, it remains to be seen how much longer this expansion will continue. As the New York Times reported,

Federal Reserve officials are beginning to worry about a possibility that seems remote to workers who still feel left behind: the danger of the economy's running too hot, destabilizing financial markets and setting off a rapid escalation in wages and prices that could force the central bank to slam the brakes on growth.

Translated, this means that if labor costs rise enough to eat into corporate profits, Federal Reserve officials will respond with interest rate hikes to slow down economic activity and weaken labor's bargaining power. And so goes the new century.

Mark Weisbrot

The Nation, August 27, 2018

Every week, and often more than once a week, there is another article in the major media or in foreign policy publications about the demise of the post-World War II Anglo-American world order. These analyses typically single out the Transatlantic Alliance between the US and Europe ― two of the world's largest economies ― for special concern and anxiety as the underpinning of this world order. Not surprisingly, President Trump's wildly fluctuating comments on NATO (despite the fact that he is expanding it), his unprecedented rudeness to European leaders, and his friendliness with Putin at the Helsinki summit have all added to the angst.

The basic story behind this moaning and melancholy is that the leaders of America put together a "rules-based" system based on "open markets" and democracy (the two are sometimes seen as synonymous) that has fostered prosperity and relative stability. The United States was the only sizable industrial economy to emerge not only unscathed, but with its economy doubled in size, following World War II. While others might have taken advantage of this unrivaled power for their own gain, the story goes, America's beneficent rulers constructed a world order for the good of everyone. Trump is seen as a threat to its continued existence.

This assessment of the post-WWII world order leaves out some three million dead Vietnamese, and half a million dead in Indonesia who might question the beneficence of this system if it had not killed them. More recently, a million dead Iraqis, if they could be heard, might also raise objections about whether American dominance has been in the interests of all. And there are hundreds of millions of people in Latin America, Africa, and Asia who suffered for decades under US-backed dictatorships, as well as US-sponsored wars. Much of the violent dysfunctionality in these countries today is a direct result of these interventions, as well as continuing US influence.

In fact, as I write this now, the US military is directly involved in a war that has deliberately produced what the UN has called the worst humanitarian crisis in the world, in Yemen. It has pushed more than eight million people to the brink of starvation, created the worst outbreak of cholera in modern history, and killed thousands of civilians in bombing raids. The United States is providing midair refueling to the Saudi and UAE bombers, intelligence, targeting assistance, on-the-ground military personnel, and more ― constrainedonly by growing opposition in the US Congress.

But let us ignore these inconvenient truths for a moment, as almost all of these analyses do.

Let's look at the present situation. The Transatlantic Alliance is much stronger than most of these analysts recognize. This is mainly because it is not just an alliance of democratic governments with shared values, but also an alliance of the rich countries of the world ― their leaders, that is ― against the poor and middle-income countries of the world.

The rules of the World Trade Organization, to which 164 countries are bound, were written by US and European corporations. The WTO's most significant achievement since its creation in 1995 was to increase US-style patent protection throughout the world, leading to the deaths of millions of poor people who could not get access to essential medicines. After years of struggle, some of these rules were rewritten, but much damage remains. The WTO's rules on agriculture also greatly disadvantage developing countries and seek to prohibit governments from subsidizing domestic production for domestic consumption to feed people who are badly malnourished, e.g., in India. WTO rules also make it much more difficult for developing countries to employ the industrial policies that high-income countries like the US used to get where they are today.

The International Monetary Fund, an organization that has 189 member countries, is run by the United States and Europe. In fact, for most of the world outside of Europe, the US Treasury Department is in charge. The World Bank, which by custom since 1946 has to have a president who is American, is also controlled by the United States and its allies, and cooperates with the IMF in promoting and imposing economic policies that Washington favors. These policies are often not in the interest of developing countries, as one would expect from organizations that are not accountable to low- and middle-income countries, or to any electorate.

These are the institutions of global governance that exercise power in the world, other than the UN Security Council, where the Transatlantic Alliance must share veto power with Russia and China. The IMF, for most of the past half century, has been the mostimportant avenue of US influence over low- and middle-income countries. It has sat at the top of a creditors' cartel, where countries who did not agree to IMF conditions would not get loans from other multilateral lenders (e.g., the World Bank) and sometimes not even from the private sector. This cartel lost influence in most middle-income countries in the first decade of the twenty-first century, but it has been coming back some (e.g., in Argentina) and still maintains its creditors' cartel in poor countries.

European leaders are quite angry about the Trump administration's unilateral abrogation of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, the negotiated agreement with Iran that had put an end to the threat that it would develop nuclear weapons in the foreseeable future. Europe clearly has much more of a security risk from the Middle East, including Trump's threatened war with Iran; not to mention all the political problems that have been created by the refugee inflow that was primarily a result of US intervention there. But what did they do about it, after their anxious pleading with Trump failed to move him? Nothing, because these leaders ― not the people of Europe, who have been screwed royally since the Great Recession ― need their beloved partner in crime.

The US is the gendarme of the rich counties' global economic and political order. This is partly because the US did not suffer the destruction that Europe did in the world wars, and partly because Europeans have developed welfare states that do not allow for the fantastically wasteful military spending that maintains 800 US military bases across the globe.

But Washington's weapons of mass and ordinary destruction are by no means its whole arsenal. The "exorbitant privilege" of being able to print the world's most important currency, which makes up 60 percent of the world's reserves held by central banks, is another. When Lehman Brothers collapsed in 2008 and the world financial crisis hit, the Federal Reserve arranged currency swaps for its European partners to make sure that they didn't suffer any temporary international liquidity problems. On the other side of the divide, if you are outside Washington's good graces, the dollarized world financial system allows the US vastly more power than other countries would have to enforce sanctions against you (e.g., in the cases of Cuba, Venezuela, and Iran), without, or even against, the United Nations' approval.

Europe's elite are bound to the rulers of the United States by virtue of their common interest in maintaining their dominance of the world economy. This is despite the reality that their spoils do not trickle down to the citizenry of the United States or of Europe.

This Anglo-American dominance won't last forever. Eurasia, the world's largest land mass, which bred the colonial powers who conquered the world, continues to increase its economic integration despite the United States' best efforts to counter this world-historical trend with its attempted TPP and TTIP commercial agreements. China's economy is already 25 percent larger than that of the US on a purchasing power parity basis. (This is the measure most used by economists for international comparisons, since it takes into account price differences between countries.) In a decade, it's projected to be about twice as big as that of the US.

Over time, European countries, led by their corporations and financial institutions, will look more to the East and less to the West as the world becomes more multipolar and the US share of the world economy shrinks. But for the near future, the US and European elite need each other as the global hegemon tries to hang on to its unelected position. Trump can be as rude, crude, and ignorant as he pleases with his European allies, but it won't make them rebel against "the leader of the free world."

Mark Weisbrot is Co-Director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington, D.C., and the president of Just Foreign Policy. He is also the author of "Failed: What the 'Experts' Got Wrong About the Global Economy" (2015, Oxford University Press). You can subscribe to his columns here.

A survey of West Virginia GDP by industrial sectors for 2022, with commentary This is content on the main page.