https://equitablegrowth.org/kate-bahn-testimony-before-the-joint-economic-committee-on-monopsony-workers-and-corporate-power/

Kate Bahn

Washington Center for Equitable Growth

Testimony before the Joint Economic Committee,

Hearing on "A Second Gilded Age: How Concentrated Corporate Power Undermines Shared Prosperity"

July 14, 2021

Thank you Chair Beyer, Ranking Member Lee, and members of the Joint Economic Committee for inviting me to testify today. My name is Kate Bahn and I am the Director of Labor Market Policy and the interim Chief Economist at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. We seek to advance evidence-backed ideas and policies that promote strong, stable and broad-based growth. Core to this mission is understanding the ways in which inequality has distorted, subverted and obstructed economic growth in recent decades.

Mounting evidence, which I will review today, demonstrates how the rising concentration of corporate power has increased economic inequality and made the U.S. economy less efficient. Reversing the trends that have led to a "second gilded age" is critical to encouraging a resilient economic recovery following the pandemic-induced economic crisis of 2020 and encouraging a healthy, competitive economy for the future.

Introduction

The United States boasts one of the wealthiest economies in the world, but decades of increasing income inequality, job polarization, and stagnant wages for most Americans has plagued our labor market and demonstrated that a rising tide does not lift all boats. Furthermore, economic evidence demonstrates how inequality results in an inefficient allocation of talent and resources while increasing corporate concentration that enriches the few while holding back the entire economy from its potential. Understanding the causes and consequences of the concentration of corporate power will guide policymaking in order to ensure that the economic recovery in the next phase of the pandemic will be broadly shared and ensure a more resilient economy.

"Monopsony" is a key economic concept to understand in this discussion. Monopsony is the labor market equivalent of the better-known phenomenon of "monopoly," but instead of having only one producer of a good or service, there is effectively only one buyer of a good or service, such as only one employer hiring people's labor in a company town. Like in monopoly, this phenomenon is not limited to when a firm is strictly the only buyer of labor. Today I will explain the circumstances and effects of employers having significant monopsony power over the market and over workers.

When employers have outsized power in employment relationships, they are able to set wages for their workers, rather than wages being determined by competitive market forces. Given this monopsony power, employers undercut workers. This means paying them less than the value they contribute to production. One recent survey of all the economic research on monopsony finds that, on average across studies, employers have the power to keep wages over one-third less than they would be in a perfectly competitive market. Put another way, in a theoretical competitive market, if an employer cut wages then all workers would quit. But in reality, these estimates are the equivalent of a firm cutting wages by 5 percent yet only losing 10 percent to 20 percent of their workers, thus growing their profits without significantly impacting their business.

It is not only important for workers to earn a fair share so they can support themselves and their families, but also critical to ensure that our economy rebuilds to be stronger and more resilient. Prior to the current public health crisis and resulting recession, earnings inequality had been growing since at least the 1980s while the labor share of national income has been declining in same period. This is cause for concern as recent evidence suggests that the labor share of income has a positive impact on GDP growth in the long-run.

The unprecedented economic shock caused by the coronavirus pandemic revealed how economic inequality leads to a fragile economy, where those with the least are hit the hardest, amplifying recessions since lower-income workers typically spend more of their income in the economy. But the crisis also demonstrated how economic policy targeted toward workers and families can provide a foundation for growth. This is because workers are the economy, and pushing back against the concentration corporate power by providing resources to workers is the foundation for strong, stable and broadly shared growth.

The Causes of Monopsony

The concept of monopsony was initially developed by the early 20th century economist Joan Robinson, who examined how lack of competition led to unfair and inefficient economic outcomes. The prototypical example of monopsony is a company town, where there is one very dominant employer and workers have no choice but to accept low wages since they have no outside options. This is the most extreme case, but it is important to note that firms have monopsony power in any circumstance where workers aren't moving between jobs seamlessly in search of the highest wages they can get.

Firms can use monopsony power to lower workers' wages any time workers:

- Have few potential employers

- Face job mobility constraints

- Can only gather imperfect information about employers and jobs

- Have divergent preferences for job attributes

- Lack the ability to bargain over those offers

I will go through each of these factors in turn and demonstrate how labor markets are unique compared to other markets in dealing with competitive forces.

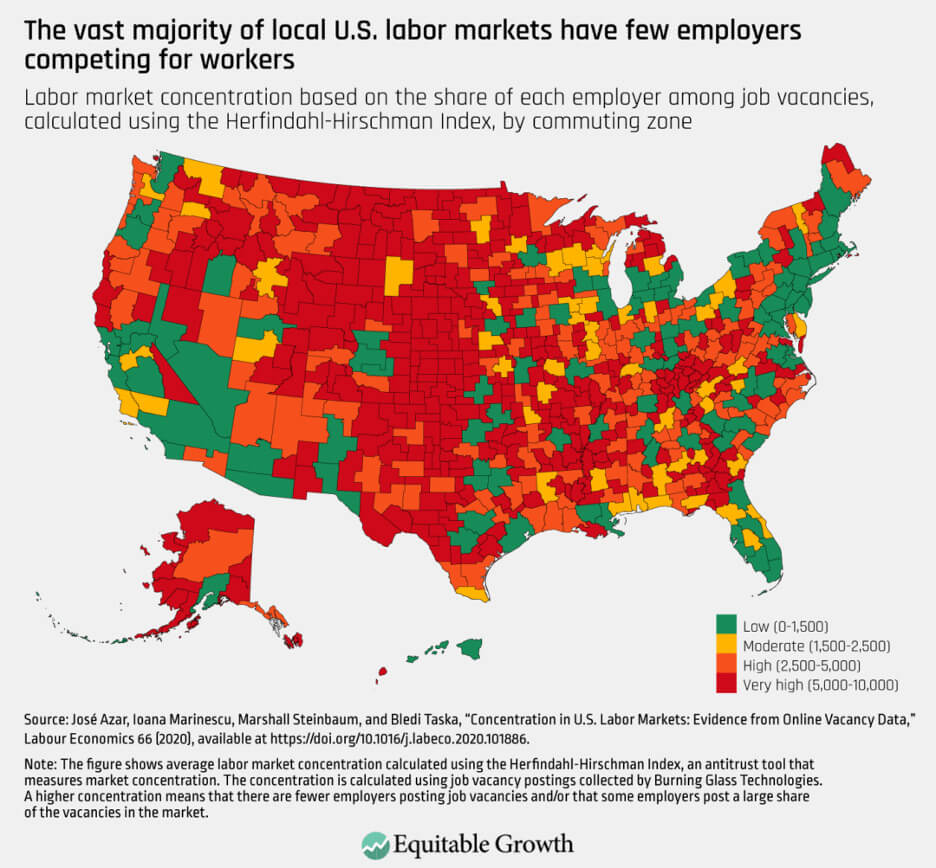

While concentrated labor markets are not the norm, they are pervasive across the United States, especially within certain sectors or locations. When markets are very concentrated, employers can give workers smaller yearly raises or make working conditions worse, knowing that their workers have nowhere to go to find a better job with better pay. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

A study published in the journal Labour Economics by economists Jose Azar, Ioana Marinescu, and Marshall Steinbaum finds that 60 percent of U.S. local labor markets are highly concentrated as defined by U.S. antitrust authorities' 2010 horizontal merger guidelines. This accounts for 20 percent of employment in the United States. Research by economists Gregor Schubert, Anna Stansbury, and Bledi Tsaka goes further by estimating workers' outside options, or the likelihood a worker is able to change into a different occupation or industry. This study finds that even with a more expansive definition of job opportunities more than 10 percent of the U.S. workforce is in local labor markets where pay is being suppressed by employer concentration by at least 2 percent, and a significant proportion of these workers facing few outside options are facing pay suppression of 5 percent or more. As study co-author Anna Stansbury noted, "for a typical full-time workers making $50,000 a year, a 2 percent pay reduction is equivalent to losing $1,000 per year and a 5 percent pay reduction is equivalent to losing $2,500 per year."

Certain sectors are now very concentrated, such as the healthcare industry. In a paper by the economists Elena Prager and Matt Schmitt, they find that hospital mergers led to negative wage growth among skilled workers such as nurses or pharmacy workers. Consolidation and outsized employer power, alongside other phenomenon such as the fissuring of the workplace, may have broader impacts on the structure of the U.S. labor market when it affects the overall structure of the labor market, including the hollowing out of middle class jobs that have historically been a pathway for upward mobility.

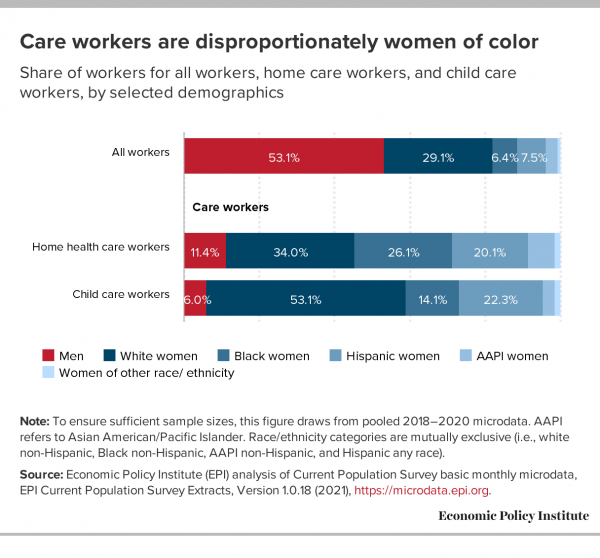

Research by sociologist Rachel Dwyer finds that job polarization in care work sectors such as healthcare, which is heavily concentrated, is a primary cause of overall job polarization in the United States, where there are fewer middle-income jobs and growing employment at the low end and the high end of the labor market. Downward pressure on wages in high-growth industries such as healthcare can impact employment opportunities for all Americans.

But as I noted, concentration is not the only source of monopsony power. Job mobility—the ability to easily move between jobs—also affects labor markets and, in turn, may give employers power to set wages below competitive levels. Job mobility can be limited by anticompetitive conduct, where employers intentionally limit the ability of their employees to find other jobs or employers collude with each other to set pay standards—even when there are technically many employers in a local labor market. Noncompete agreements, where workers sign away their right to go work for a direct competitor of their employer, have become pervasive, including among low-wage workers where there is arguably no justification to limit worker mobility due to the necessity to protect trade secrets.

Research by economists Evan Starr and Michael Lipsitz found that after the Oregon state ban on noncompete agreements in 2008 job mobility increased by 12 percent to 18 percent and wages grew 4.5 percent more in occupations with high noncompete usage compared to those with low noncompete usage. The Executive Order by the Biden Administration released on Friday, July 9, explicitly asked the Federal Trade Commission to ban or limit these agreements.

But other factors influence mobility between jobs, including transportation networks and personal constraints on commute time. The greater importance of a shorter commute time for women workers contributes to the gender wage gap since it limits women's job searches. Employer-provided healthcare discourages changing jobs, or what economists' call "job lock." Research by economists Adriana Kugler and Ammar Farooq found that more generous Medicaid eligibility reduced job lock and increased the likelihood that workers changed jobs into higher paying occupations. A variety of real-life factors affect how workers switch jobs, which in turn can affect how much power employers will have over setting wages.

Asymmetric information between employers and workers also influences how workers sort between jobs and puts downward pressure on wage offers. Workers often know little about the salary range at potential employers or even within their own firms. A "salary taboo" discourages workers from asking their colleagues their salary or disclosing their own. In contrast, employers know what all their employees are paid and often require applicants to disclose their current salaries or competing job offers, giving them much more information to work with.

In scenarios where a new salary transparency regime was instituted, such as one study of public-sector workers in California, workers were more likely to quit their jobs once they knew the pay scales within their workplaces, which, in effect, is a competitive market response to greater information. Likewise, employers may have imperfect information about the ability of job applicants, so wage offers to new employers may not be connected to workers' abilities.

And finally, heterogeneous worker preferences, where individual preferences for attributes of jobs are unique and varied, also gives employers the power to undercut wages. Workers are not fully compensated for the tradeoff between their preferences and the job offers employers make. Workers who are more likely to face hostile work environments, among them Black workers in primarily White occupations or women in male-dominated fields, may prefer workplaces that are more inclusive. Or parents who have primary responsibility for caretaking for their children may need more a predictable schedule or autonomy over their schedules. But research on so-called compensating wage differentials finds that workers are not fully compensated for these imperfect tradeoffs the make in their job choices.

How Monopsony Exacerbates Economic Disparities

The concentration of corporate power has dire consequences for workers who are already disadvantaged in the U.S. economy. Regional economic divergence between urban and rural areas is exacerbated when there are few job options for workers in less-populated parts of the country. Workers facing hiring discrimination will have fewer job offers, so they'll be forced to accept substandard opportunities. Outside life circumstances, such as being the primary caretaker for children in a family as women are more likely to be, may limit the scope of a worker's job search. And having an unstable fallback position, without personal wealth or adequate income supports, may reduce the ability of a worker to search for a job that is both the best fit and garners the highest possible wages. Employers are able to exploit these conditions by undercutting workers' wages without risking losing their labor supply, amplifying the negative consequences of rising corporate power.

The rise of monopsony across the United States has heightened economic challenges in particular in rural areas, depressing wages below what they would otherwise be. Labor markets in rural areas are much more likely to be concentrated, which may partially explain why urban labor markets have higher wages where competition for workers is higher. As researcher Zoe Willingham and economist Olugbenga Ajilore have written, this has amounted to the reemergence of the modern company town in many rural areas. One case in point: Research by economist Justin Wiltshire finds that Walmart Supercenters push down both earnings and employment across the counties where they were opened compared to counties where a Walmart Supercenter was proposed but blocked locally. Walmart is able to do this because in those counties it is the dominant employer of retail workers, giving it the power to set wage rates, compared to areas where there were many different retailers competing for workers.

My own research with economist Mark Stelzner examines how external conditions of structural racism and sexism give individual employers the ability to exploit workers along the lines of race, ethnicity, and gender. One such way is that the vast wealth divide between Black, Latinx, and White Americans makes it harder for Black and Latinx workers to search for jobs when taking time out of the labor force exposes them to a much greater financial risk. If Black and Latinx workers don't have the financial cushion to maintain job search periods without income or adequate income support such as Unemployment Insurance, then they are less likely to quit jobs that offer low wages or poor working conditions.

Women workers also face unique barriers, such as hostile working conditions including sexual harassment. Insufficient legal protections or workplace recourse can leave women neither able to combat the harassment nor leave their jobs without wealth to manage the search for a job with better conditions. The result is employers facing little risk of their workers quitting, giving them the power to undercut wages. And women workers face additional constraints to job mobility imposed by a disproportionate care burden within families. If a woman is the primary caretaker for children or other family members with care needs, then this will reduce the geographic scope of her job search and may limit acceptable job schedules. This results in women being less likely to move around for jobs within their occupation in search of the best pay they can receive.

The aggregate result of these individual family constraints are employers' ability to offer women lower wages. Research on teachers has found that women teachers are over-represented in lower paying school districts, which may be partially explained by women's lower ability to search around for the highest paying position. On top of this, within school districts pay differences between women and men are also significant, which demonstrates how lower bargaining power for women persists despite rigid pay structures.

Mainstream economic orthodoxy has argued that wages are set by competitive forces, so proactive policies to raise wages and increase worker power would limit the potential for economic growth that comes from competition. Yet the broad research indicates that the U.S. labor market is anything but competitive, including evidence that monopsonistic labor markets give employers the power to suppress wages by more than one-third. In fact, one insight from the monopsony framework developed by Joan Robinson in the early 20th century is that raising wages and increasing worker power actually encourages the outcomes that would exist in a competitive labor market, with greater earnings alongside higher employment levels.

How to Push Back on Corporate Power Through a Robust, Pro-Competition Policy Agenda

Reversing the trends that caused this "Second Gilded Age" starts with ensuring that the U.S. economy is competitive. Robust antitrust enforcement of existing laws against concentration and anticompetitive conduct is the first step toward ensuring that economic progress is shared between workers and employers. The Biden Administration is also starting to strengthen enforcement against anticompetitive conduct, including excessive use of non-compete agreements. But this can go further, including new laws that would codify, clarify, and strengthen antitrust law for labor markets. Without significant legal precedent for antitrust protections in labor markets, enforcers have little recourse to protect workers, but legislation can pave the way.

But antitrust actions alone are not sufficient when the sources of monopsony power also come from inherent, unique features of the U.S. labor market compared to other markets such as commodities. For this reason, another important way to address the concentration of corporate power is to build countervailing power for workers. In practice, proposed policies—such as the Protecting the Right to Organize Act that would expand the ability of unions to organize workers alongside institutions, including a more effective National Labor Relations Board, which upholds current U.S. labor organizing laws, with modern enforcement capabilities—would limit employers' ability to exploit workers along multiple axes. The need for more pro-labor policies is increasingly evident as employers' monopsony power mounts, given the inverse relationship between decreasing worker power as measured by union density and rising income inequality, partially due to an anti-labor policy and institutional environment since the 1970s, and as racial and gender wage disparities remain persistent and are likely to worsen due to differences in unemployment amid the coronavirus pandemic.

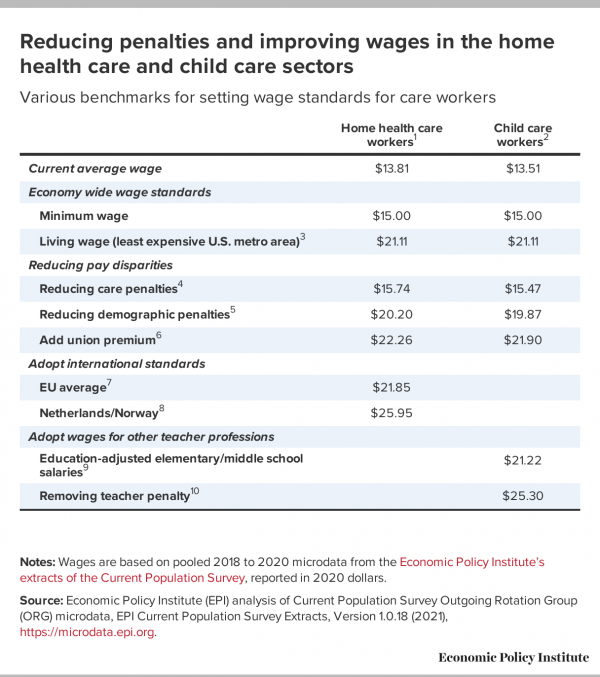

One feature of a monopsonistic labor market is that wages are artificially suppressed, so there is room to raise the floor with tools such as increasing the minimum wage and exploring the possibility of wage boards. Minimum wages have been shown to be a critical tool for reducing the wage divide between Black and White workers, and the falling real value of the minimum wage has exacerbated pay disparities. Increasing the statutory minimum wage would limit the ability of employers to exploit the conditions of structural racism. Going beyond this could include wage boards, which would raise wages within occupations or industries, such as has been done in Arizona, Colorado, California, New Jersey, and New York. In a monopsonistic labor market, raising wages with these tools replicates the labor market outcomes that would exist in a hypothetical perfectly competitive market.

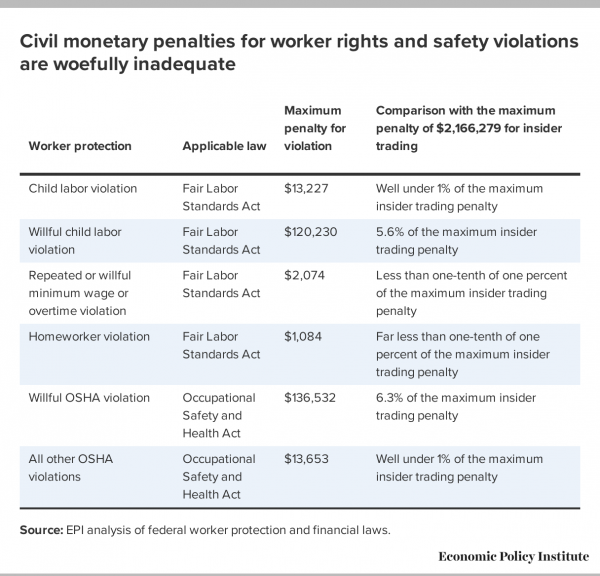

Finally, giving workers universal protections and the social infrastructure policies discussed in my testimony would provide a stable foundation for workers to search for quality jobs where they can be as productive as possible and earn the value they contribute to the economy and society. This includes effective anti-discrimination enforcement and workplace safety standards to ensure workers receive job offers and equitable pay and are not stuck working in hostile environments. This includes family economic security policies that help families manage care needs and engage in the labor market, such as paid family and medical leave, paid sick time, accessible and affordable childcare, and scheduling stability, giving workers more space to find the best fit for their employment. And this includes income supports that give workers an outside option so they can find better jobs. Unemployment insurance expansions and Medicaid expansions have both been shown to increase the likelihood that workers will match into higher paying jobs. Building the foundation of security for workers not only directly impacts their wellbeing but also provides the foundation for productivity growth through better job matches and stronger economic growth through increased incomes. Boosting workers' economic security is an effective tool for pushing back against the tide of concentrating corporate power.

The post Kate Bahn testimony before the Joint Economic Committee on monopsony, workers, and corporate power appeared first on Equitable Growth.

-- via my feedly newsfeed