https://equitablegrowth.org/the-rising-financialization-of-the-u-s-economy-harms-workers-and-their-families-threatening-a-strong-recovery/

If you are an analyst following Wall Street, things are looking pretty bright these days. The S&P 500—an index of 500 major publicly traded companies in the United States and a benchmark for gauging the health of the U.S. corporate sector—is up more than 80 percent since its low in March 2020 during the onset of the global pandemic.1 Companies in the index have added $50 trillion worth of value during the course of the lockdowns and recovery, a rally not seen since the post-Great Depression period 90 years ago.2

Meanwhile, how Main Street is faring is a bit more complicated. While the U.S. economy added a healthy 916,000 jobs in March 2021 and the unemployment rate fell to 6 percent, there are still 8.4 million fewer jobs than before the pandemic.3 And job gains during the incipient recovery are driven predominately by the strength of employment for White workers. Black men are still experiencing an unemployment rate of 9.6 percent—almost double that of White men—and Black women actually saw their unemployment rate slightly increase to 8.7 percent in March.4

What's more, this disparity comes at a time when Black women have already dropped out of the workforce at staggering rates. Their employment-to-population ratio dropped 6 percentage points since just before the pandemic, double the rate of White women's withdrawal from the workforce.5 Latina women face a similar set of challenges as Black women, with the unemployment rate for Latina women at 7.3 percent and the employment-to-population ratio also still far below pre-pandemic levels.6

By now, many policymakers have heard the story of the so-called K-shaped recovery.7 This describes how the fortunes of those at the top of the U.S. wealth and income ladders can be so disconnected from the experiences of U.S. workers and their families, especially those struggling the most in our economy. Even as U.S. policymakers' economic response to the coronavirus pandemic was relatively robust, compared to other countries,8 the gap between the rich and nonrich in the United States is still among the largest in the world.9

In short, even a strong rescue response can't make up for decades of disinvestment. So, what policy choices led to the growing divide between the wealthy and the rest of us? How did U.S. policymakers enable these inequitable economic outcomes?

On April 29, a hearing of the U.S. Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs explored that question, within their remit of banking and financial services: What are the mechanisms by which finance, enabled by public policy, made this the case?10 The hearing delved into the channels through which our financial markets have put the squeeze on U.S. workers, drawing on testimony from Trevon Logan, an Equitable Growth grantee and the Hazel C. Youngberg Trustees distinguished professor of economics at The Ohio State University; Heather McGhee, board chair of the advocacy group Color of Change and author of the new book The Sum of Us: How Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together; and Lisa Donner, executive director of Americans for Financial Reform, an organization focused on strengthening our financial system.11

This issue brief explores their testimony, alongside other evidence-based research and analysis. The brief details how the financialization of the U.S. economy over the past five decades contributed to income and wealth inequality, stifled economic growth, and exacerbated economic disparities by race and ethnicity. It then presents some policy ideas put forth by the witnesses at the hearing, including solutions to short-circuit financialization by investing in physical and care infrastructure, building worker power, ensuring strong regulation of our financial system, and improving fairness in our tax system.

How Wall Street harms U.S. workers and their families

Witnesses at the hearing on April 29 explored how Wall Street harms U.S. workers and their families through the phenomenon known as "financialization." Financialization refers to the process by which the financial sector—banks, private equity firms, hedge funds, stocks and derivatives exchanges, and other conduits through which money flows between those who have it and those who need it—takes up a larger and larger share of the U.S. economy, fails to allocate capital to its most productive uses, and increasingly results in the hoarding of economic, and thus political, power at the top of the income and wealth ladders.

Financialization also can refer to the increasing participation of nonfinancial businesses in financial activities. General Electric Company, for example, a company most people associate with manufacturing and innovation, earned 43 percent of its profits from financial activities as recently as 2014.12

As explored in the hearing, financialization can create downstream harm for U.S. workers and their families by undermining what Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-OH), chairman of the Senate Banking Committee, calls "the dignity of work." Sen. Brown borrowed the phrase invoked by Martin Luther King Jr. in defense of striking workers in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1968. The phrase means that all people's labor is compensated fairly, that employment is free from exploitation and coercion, and that work—whether inside or outside the home—is respected and met with dignity.

How financialization took hold over the past 50 years

Witnesses at the hearing identified the shift to "shareholder capitalism" over the past five decades as a key framework for understanding how financialization has been operationalized. Over the past half-century, corporate leaders, influenced by the free-market economists of the Chicago School, shifted the views of the majority of financiers from the need to support jobs and the communities in which they operate to a focus on the maximization of short-term shareholder value.13 In the words of Milton Friedman in 1970, the goal of corporate managers is to "conduct business in accordance with (shareholders') desires, which generally will be to make as much money as possible while conforming to the basic rules of the society, both those embodied in law and those embodied in ethical custom."14

The import of Friedman's statement is that considerations such as worker welfare, the economic health of communities, the environment, and U.S. competitiveness on the world stage were best left to policymakers and civil society leaders, with business leaders' only obligation being the maximization of profits. This philosophy formed the underpinnings of not just a change in managerial practices but also in business education.15

The problem with this narrowing of focus on the part of corporate leaders is that policymakers—the stewards of public welfare in this ecosystem—failed to keep up, as large businesses and finance entrenched the excesses of shareholder value to harm workers. In fact, as witnesses at the hearing documented, corporate leaders themselves use their outsized economic power to influence the policymaking process in their favor, for example, by eroding the worker protections and financial system regulations established after the Great Depression. This has created feedback loops where enhanced economic power begets more political power, with workers increasingly short-changed.

How financialization shapes the U.S. economy today

How does financialization manifest itself throughout the U.S. economy today and, especially, in how policymakers measure the success of the economy?

For one, the share of income accruing to workers continues to decline. The so-called labor share of income represents the percentage of U.S. Gross Domestic Product paid out in the form of wages, salaries, and benefits and can be contrasted with capital's share of income, which is the money made off of investments or the ownership of things. As economist Dean Baker at the Center for Economic and Policy Research points out, if the labor share of income were the same just before the pandemic as it was in 1979, the median worker's pay would be about 4.2 percent higher than it is now.16

Financialization can decrease the labor share of income in two ways: by increasing the amount of income derived from capital and then by decreasing the amount of income derived from labor. On the first point, while factors such as technological innovation and globalization can drive up the capital share of income, financialization also plays a role, as companies increasingly earn money through financial engineering rather than investment in people. According to one estimate, financialization may have contributed to more than half of the fall in the labor share of income.17

Moreover, financialization, enabled by the gutting of worker power discussed more below, can also decrease the labor share of income by increasing the pressure on short-term profit maximization, driven, in part, by decreasing labor costs. This phenomenon is exemplified by Wall Street analysts downgrading the stock of the restaurant chain Chipotle Mexican Grill Inc. because they concluded that management had exhausted their ability to reduce hours or cut wages of front-line workers.18

Financialization also widens the disparities between people who earn their money in the financial-services industry versus workers who earn it elsewhere. Economists Josh Bivens and Lawrence Mishel at the Economic Policy Institute documented how the overall pay of financial-sector workers relative to others in the economy has risen substantially over the past decade.19 While the ratio never exceeded 1.1 percent from 1952 to 1982, it began rising and reached 1.83 percent by the onset of the Great Recession of 2007–2009.20

Likewise, research by Thomas Philippon at New York University's Stern School of Business and Ariell Reshef at the Paris School of Economics shows a pay premium for finance workers even when multiple controls, such as education and employment risk, are used. The authors conclude that roughly 30 percent to 50 percent of the pay premium in finance is due to economic "rents," or policy failures that allow a market to exist out of equilibrium.21

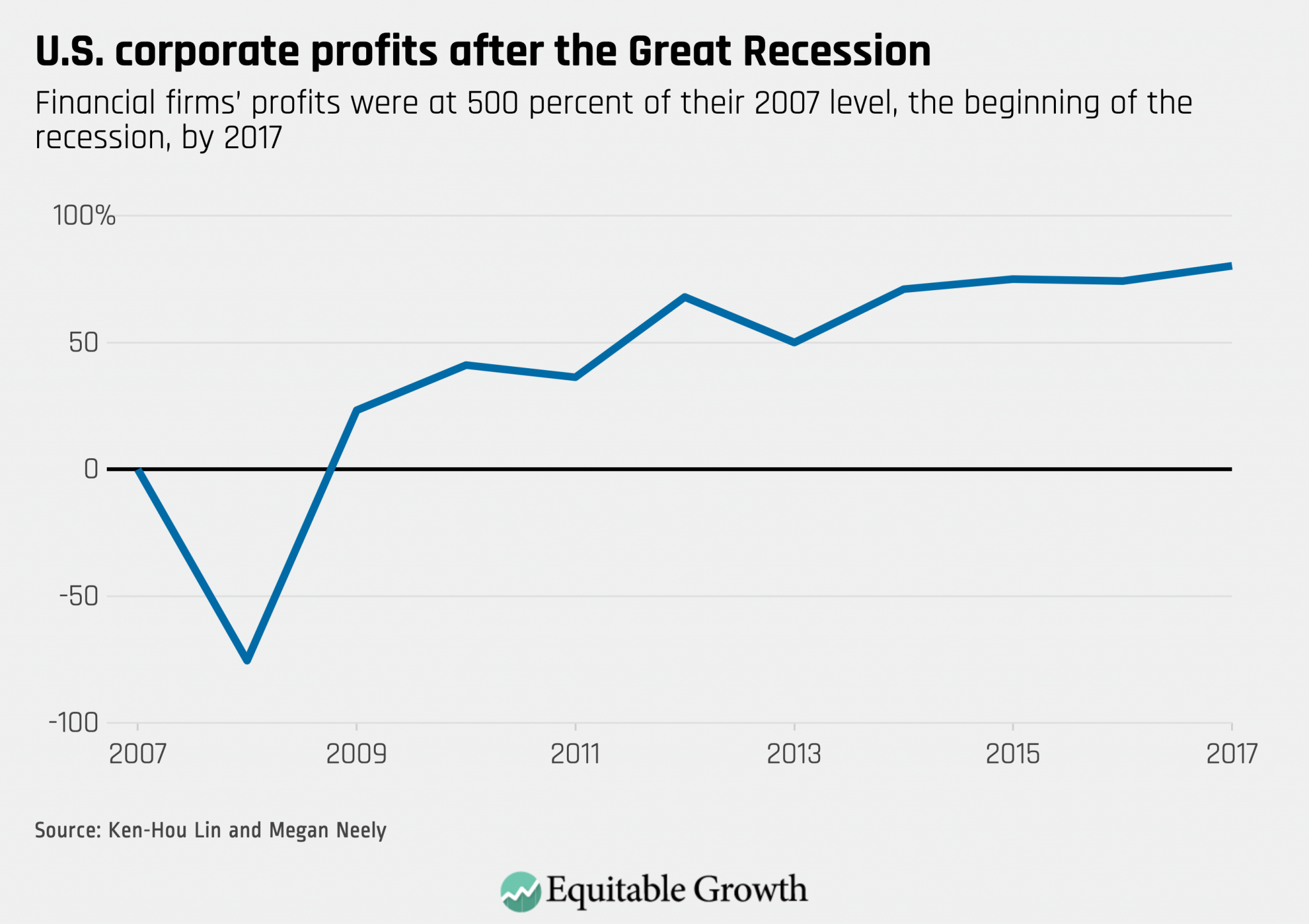

Further, the profits of financial firms comprise a greater share of all corporate profits and of total U.S. GDP. In her April 29 testimony before the Senate Banking Committee, Donner of Americans for Tax Reform presented U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis data to show that financial-sector profits and their share of GDP have skyrocketed since the 1970s.22 (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

And despite the growth of the finance industry, the costs of intermediation—the toll taken by financial-services firms to funnel money between savers and spenders—are about the same as they were a century ago.23

Finally, financialization can impede overall economic growth, dragging the entire global economy down. Researchers from the Bank for International Settlements surveyed international economies and found that financial booms can create "bloat" in the global economy that drags resources away from productive activities and into nonproductive trading and speculation.24 Further, according to Adair Turner, a former British banking regulator, only 15 percent of financial flows actually fund new projects and jobs in the global economy, with the rest going toward securitizing and speculating on existing assets.25

As pointed out by Color of Change's McGhee in her testimony, the subprime mortgage crisis of 2008 is the paradigmatic example of this phenomenon, with a relatively small number of toxic mortgage loans, sold disproportionately to Black and Latinx individuals and families, able to cause a global financial crisis due to the magnifying effect of financial derivatives.26

Financialization is supercharged by policy choices

Financialization isn't natural law or the logical outgrowth of improving technology or a changing economy. Instead, it is driven by policy choices motivated by Friedman's ethos taking hold among economists and policymakers alike. Tax policy, for example, encourages executive compensation structures that focus on short-term gains over long-term value creation by making performance-based equity awards tax-deductible for corporations.27 Compensation in the form of unrestricted stock can encourage CEOs to pursue juicing share prices over long-term value creation, particularly as 43 percent of CEOs admit to having a planning horizon of 3 years or less.28

The swirl of tax policy and shareholder supremacy also leads to an increasing number of firms using profits to enable capital distributions to stockholders in the form of dividends and share repurchases, rather than investment in longer-term growth. Research suggests that this short-term focus encourages companies to increasingly focus on financial engineering rather than slow and steady value creation. In fact, some research suggests that capital markets actually reward companies with the highest levels of share repurchases rather than the firms with the highest growth potential.29

These phenomena are further exacerbated by the tax deductibility of interest payments on debt. This leads to firms not only privileging capital distributions over investments in their own operations and future growth, but also to relying on debt to do so. Recent data suggest that about half of share buybacks are financed by debt.30 While the Tax Cut and Jobs Act of 2017 did limit some of the deductibility of interest on corporate debt payments, the windfall to firms from reduced tax bills was met with declining business investment and tepid wage growth, even before the onset of the pandemic and recession.31

Laggard antitrust enforcement is another reason why firms are able to exercise outsized control in their markets, harming workers and their families and decreasing innovation in the broader economy. Researchers hypothesize that lax antitrust enforcement allows firms to sidestep competitive market forces as firms no longer have to invent new technologies or improve services when their market position allows them to extract monopoly profits. Common ownership by institutional investors also can lead to businesses competing less vigorously against one another.32

When combined with the legislative and judicial erosion of worker power over recent decades, these firms can easily exercise outsized control over their workers. Ohio State economist Logan in his testimony points to the coercive control exercised by firms not only via low wages but by policies such as limiting bathroom breaks or social interaction with colleagues, requiring entry-level employees to sign nondisclosure agreements that foreclose on their ability to switch jobs, and using aggressive tactics to prevent collective bargaining.33 Workers of color are disproportionately represented in jobs governed by what Logan, in his testimony, calls "factory discipline," or the ability of managers to exercise de facto authoritarian control, underscoring the racialized harm caused by monopsonistic behavior.34

Financial deregulation also plays a role. Donner's testimony describes the process by which Wall Street eroded bank safety and soundness protections, defeated laws governing predatory mortgages, prevented measures to bring transparency to financial derivatives markets and weakened corporate accounting and governance rules in the lead-up to the Great Recession.35 In turn, financial crises inevitably harm vulnerable communities much more than they hurt the financial sector itself. While the Great Recession wiped out almost three-quarters of financial-sector profits, the sector had fully recovered by midway through 2009.36 (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Meanwhile, it took a decade for wages to recover to pre-Great Recession levels.37 As Heather McGhee points out in her testimony, communities of color are most likely to suffer earliest and harshest during financial bust periods—and in the 2008 crisis, were both the targets of predatory financial behavior and the last to recover from its effects.38

Finance itself is financialized

The banking sector itself perhaps provides the best case by which to illustrate the feedback loops caused by financialization. The largest U.S. banks benefitted from record revenue in trading in 2020 and early 2021, profiting from volatility across equities, fixed income, currencies, and commodities during the pandemic and the Fed's intervention in the markets.39 Meanwhile, loans to consumers and small businesses remained flat. Bank executives contend that weak loan demand is driving the lackluster lending volumes.40 Yet community banks have continued lending at nearly 2.5 times the rate of noncommunity banks.41

Other research evidence suggests that large bank concentration in a community can impede lending to the real economy. One study conducted during the policy response to the coronavirus pandemic finds that a small business merely being located in an area predominately served by megabanks lowered the chances of an eligible small business receiving a Paycheck Protection Program loan.42 The lack of connection between Wall Street profits and provision of credit in the real economy is particularly troubling, given the regulatory forbearance afforded to big banks by U.S. financial agencies during the pandemic recovery in the name of jumpstarting lending.43

Meanwhile, front-line bank workers themselves have been exposed to significant risk during the pandemic, protesting a lack of personal protective equipment and intense stress from having to coach customers in navigating an economic crisis.44 At the same time, bank workers' pay remains modest, with 75 percent of bank workers earning less than $15 an hour and about a third of bank workers relying on some form of public assistance to make ends meet.45 People of color are overrepresented in front-line bank positions such as tellers and underrepresented in senior management roles.46

Lisa Donner in her testimony also pointed to the private equity industry as being at the nexus of many of these phenomena.47 Emboldened by favorable tax treatment of their debt-driven business operations and a focus on short- to medium-term value creation, private equity funds buy up floundering companies, typically increase those companies' debt levels, and seek to minimize business costs—most notably, labor costs. Some private equity funds may bring management expertise or process improvements to the businesses they own, but some research also shows that private-equity-owned firms are more likely to default on loans related to large buyouts.48 They also are more likely to go bankrupt.49 And they are more likely to cut jobs and reduce wages than similarly situated firms with other ownership models.50

Over the past year, research also suggests that private-equity-owned businesses such as nursing homes have a higher incidence of death among residents.51 And private-equity-owned hospitals were quicker to cut practitioners' pay and benefits at the onset of the pandemic.52

Solutions to rising financialization

Witnesses at the April 29 hearing pointed to a number of policy solutions to these challenges. The $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan, enacted in March 2021, directed substantial aid to those suffering the most from the pandemic and the recession it created, with $1,400 direct payments, an expanded refundable Child Tax Credit, and strengthened Unemployment Insurance compensation and child care investments. All are likely to improve the lives of those affected and help grow the U.S. economy.

Further efforts proposed in the $2.3 trillion American Jobs Plan and $1.8 trillion American Families Plan can help entrench those investments so that structural changes in the economy will help workers and their families more sustainably as the economy recovers.53 These policy actions and proposals, if fully implemented, would help correct the disinvestment in public institutions that began in the 1970s—timed just as our legislative and judicial systems removed formal barriers to access for people of color and thus removed an important counterweight to the forces of financialization.

The Senate Banking Committee also heard testimony on April 29 about other policy changes that could combat the deleterious effects of financialization. Ohio State's Logan emphasized ways to empower workers by using antitrust enforcement to break up monopsonistic power and break the feedback loops created by financialization.54 Donner discussed how to rein in the outsized power at the very top of the U.S. wealth and income ladders by strengthening the rules and regulations governing Wall Street's rising control of the U.S. economy. Specifically, she wants policymakers to address concentration among banks, strengthen protections against predatory lending, and reform the tax code to end the favorable treatment afforded to income gained via investments rather than labor.55

All of the witnesses also discussed the need to enact policy that addresses the roots of systemic racism, which is deeply interlinked with the causes and consequences of financialization. As McGhee pointed out, the legacy of the racial wealth divide is maintained and exacerbated by financialization, which pulls income away from workers and their families and directs it to those already exceedingly wealthy. Those with the least savings—mostly families of color historically cut off from wealth-building opportunities—are left the furthest behind, with fewer and fewer opportunities to catch up.56

On this point, witnesses also provided a host of policy recommendations to address economic disparities by race and ethnicity. They recommended that policymakers should collect more and better data, disaggregated by race and ethnicity,57 to provide better measures of the U.S. economy. Another suggestion was to enact policies such as baby bonds so that children have assets to help enable wealth-building activities as they head into adulthood.58 A third proposal would be to support worker power to help level the playing field between wage-earners and increasingly powerful corporations.59 Another recommendation was to examine how minority-owned small businesses were left behind in previous rescue efforts, including in response to the coronavirus recession.60 And more broadly, they recommended protecting against financial deregulation, which increases the risk of predation and its economic fallout for Black and Latinx individuals and families.61

The roots of financialization run deep, and its causes stretch far beyond the U.S. banking and financial-services sector. But with a broad set of investments in workers and families, policymakers can reverse these harmful decades-long trends and build a framework for sustained and broadly shared prosperity.

The post The rising financialization of the U.S. economy harms workers and their families, threatening a strong recovery appeared first on Equitable Growth.

-- via my feedly newsfeed