https://equitablegrowth.org/the-evidence-behind-bidens-big-plans-for-rebuilding-infrastructure-reducing-poverty-and-combating-inequality/

During his first 100 days in office, President Joe Biden turned core elements of his Build Back Better campaign plan into concrete policy proposals for congressional consideration. Dubbed the American Jobs Plan and the American Families Plan, his two most recent proposals are designed to complement the temporary economic boosters included in the American Rescue Plan—legislation, passed by Congress and signed by the president in March, focused on addressing the coronavirus recession.

The American Jobs Plan and the American Families Plan, though, would go further than the American Rescue Plan. President Biden's two new plans would make large-scale, and in some cases permanent, investments in the nation's physical and human infrastructure, combating racial, income, and wealth inequality and restructuring large parts of the U.S. economy. As 225 leading economists explained in a letter to Congress earlier this month, these proposals, if designed correctly, could promote strong, stable, and broad-based economic growth. And indeed many of the big ideas included in the two new plans are backed by extensive academic evidence, much of which has been funded and featured by the Washington Center for Equitable Growth.

Let's walk through the major elements of the administration's new plans, which were outlined by the president in a joint address to Congress last night, alongside the underlying academic evidence, in turn.

American Jobs Plan

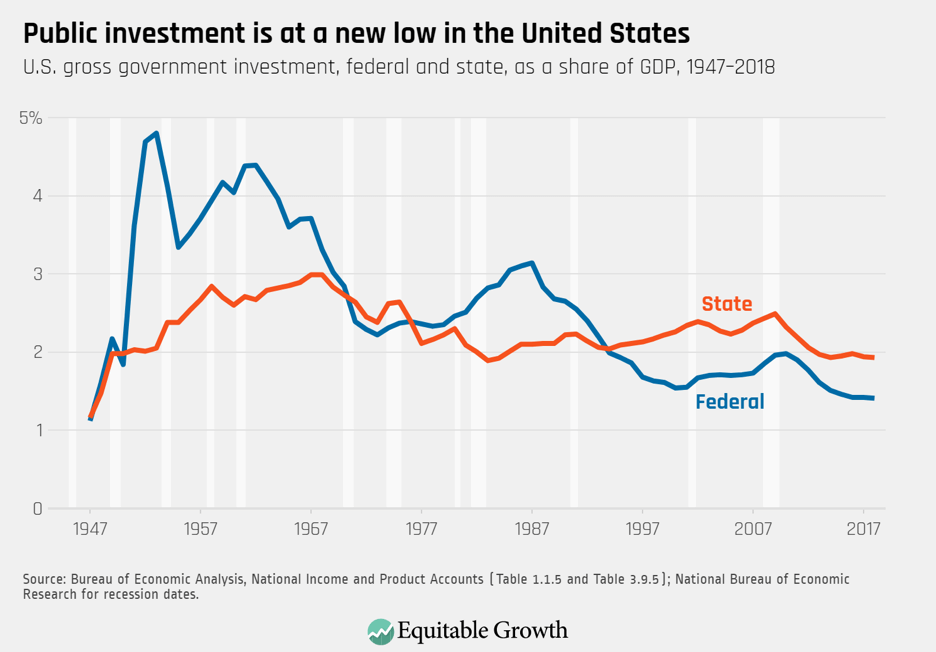

In total, this plan includes $2.3 trillion in public investments in physical and human infrastructure, science research and technological development, and climate change mitigation and environmental justice. It would begin to reverse the decades-long downward trend in government investment. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

We know from academic research that the decline in public investments has weakened growth and increased inequality. Specific policies in this plan to address these weaknesses include:

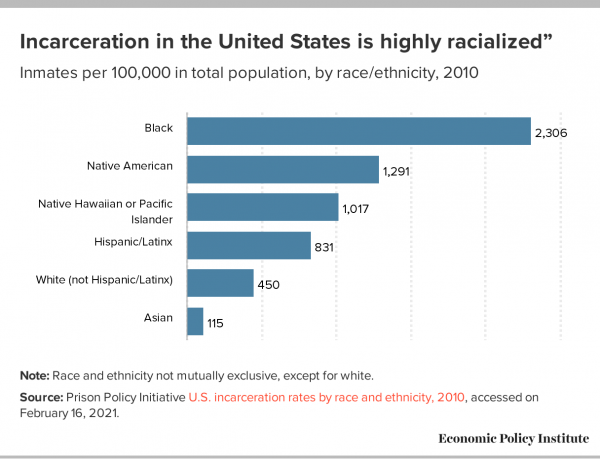

- Nearly $1 trillion for upgraded transportation infrastructure, including roads, rail, and bridges; improved water systems; expanded broadband; and enhanced electricity grids. Black, Latinx, and Indigenous communities suffer disproportionately from long commute times, unsafe drinking water, and unreliable broadband access, so these investments will begin to address our country's insidious racial inequities.

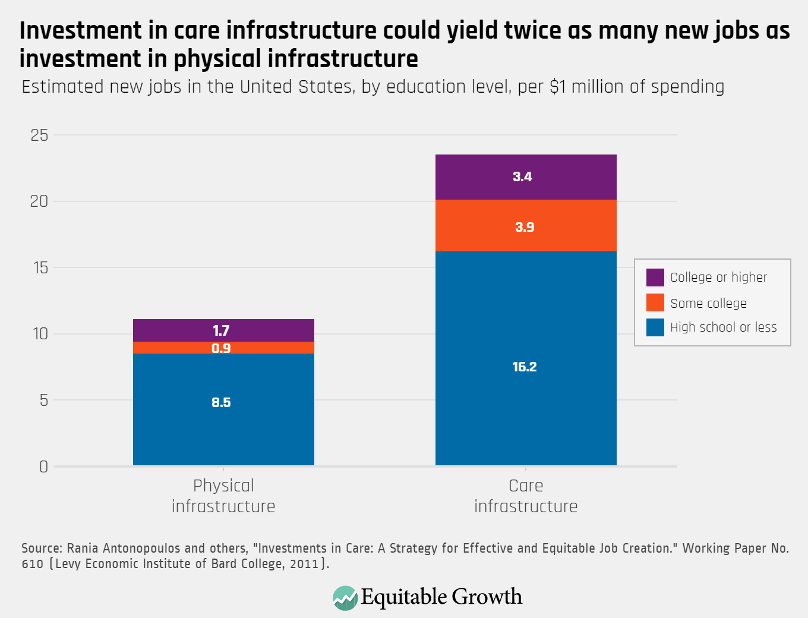

- A $450 billion investment in long-term care services and supports through Medicaid. As nearly 200 social scientists wrote in a recent letter to Congress, this investment will improve care for our aging population and invest in long-term care workers, who are today largely underpaid women of color. Improving job quality for care workers helps the workers themselves, prevents patient deaths by improving the quality of care, and is good for the U.S. economy. In fact, this type of investment in "care infrastructure" boasts the potential to create twice as many new jobs as investments in physical infrastructure alone. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

- The Protecting the Right to Organize, or PRO, Act, which would modernize decades-old labor laws to address the growing power imbalance between workers and businesses. It would make it easier for workers to organize and collectively bargain, thus ensuring that the millions of jobs created by the American Jobs Plan are high-quality positions that include fair pay, predictable schedules, and good benefits, among the other advantages of unionization.

- The American Jobs Plan also calls on large, profitable firms to pay more in corporate tax to help finance these investments. Though the federal government has the fiscal capacity needed to deficit-finance the growth-enhancing investments included in the American Jobs Plan—and research shows that previous concerns about deficits and debt are overblown—many U.S. corporations have prospered throughout the coronavirus recession and received large and economically wasteful tax cuts in 2017, so raising revenue from them is both fair and consistent with strong, stable, and broadly shared growth.

American Families Plan

The American Families Plan, released by the White House yesterday, is all about human capital investments and enhancing the nation's social infrastructure so that children are not raised in poverty, have access to high-quality pre-Kindergarten and child care, and families can better balance caregiving and work obligations. Specific policies in this $1.8 trillion plan include:

- Guaranteeing all workers access to paid family, medical, and sick leave. Today, only 20 percent of private-sector workers access paid family leave through their employers, and 44 percent of U.S. workers do not even qualify for unpaid leave through the Family and Medical Leave Act. This leaves many workers with the impossible choice of caring for loved ones or keeping their jobs. And caregiving responsibilities are a significant driver of women's exit from the labor force, which helps explain why the U.S. women's labor force participation rate was 56.1 percent in March 2021, a 33-year low. Women of color have been hit the hardest by the collision between caregiving responsibilities and the coronavirus pandemic.

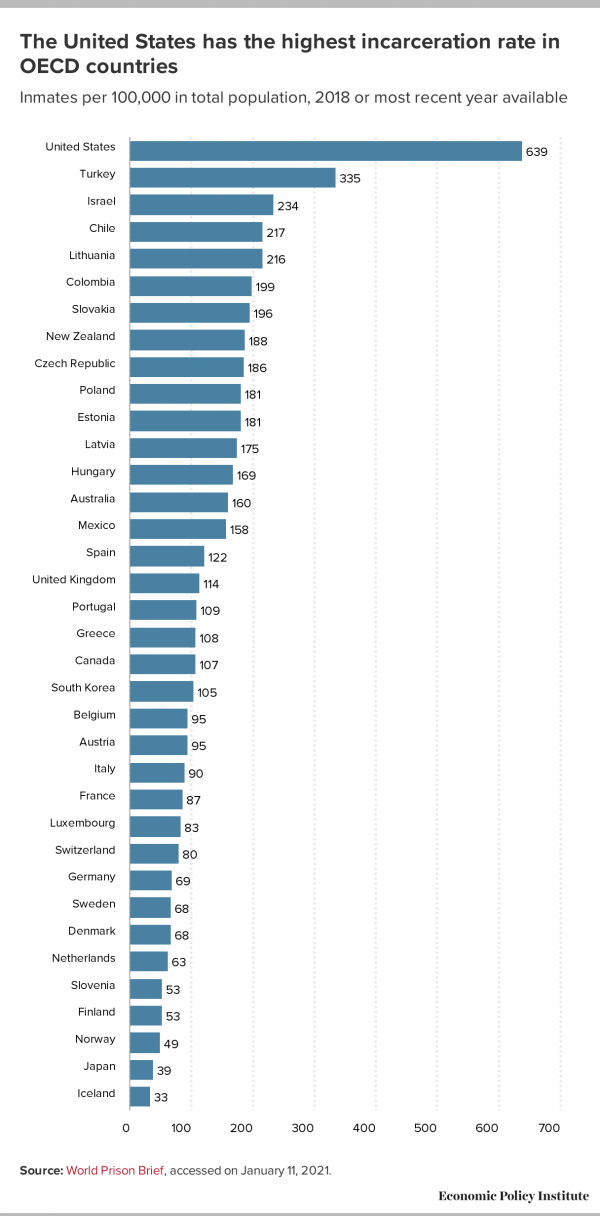

- Expanding access to high-quality child care options through a $225 billion investment and a permanent extension of the enhanced Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit. Research shows that parents' labor force participation increases when child care is more affordable and accessible. In one study, a $100 increase in the price of child care is associated with a 3.7 percentage point decrease in that neighborhood's labor force participation rate among women. Meanwhile, high-quality early care and education can lead to long-term improvements in a child's human capital. Children in high-quality programs demonstrate better education, economic, health, and social outcomes and fewer negative outcomes—such as deleterious involvement in the criminal justice system. These high-quality programs can help pay for themselves, generating up to a 13 percent return on investment per-child, per-year.

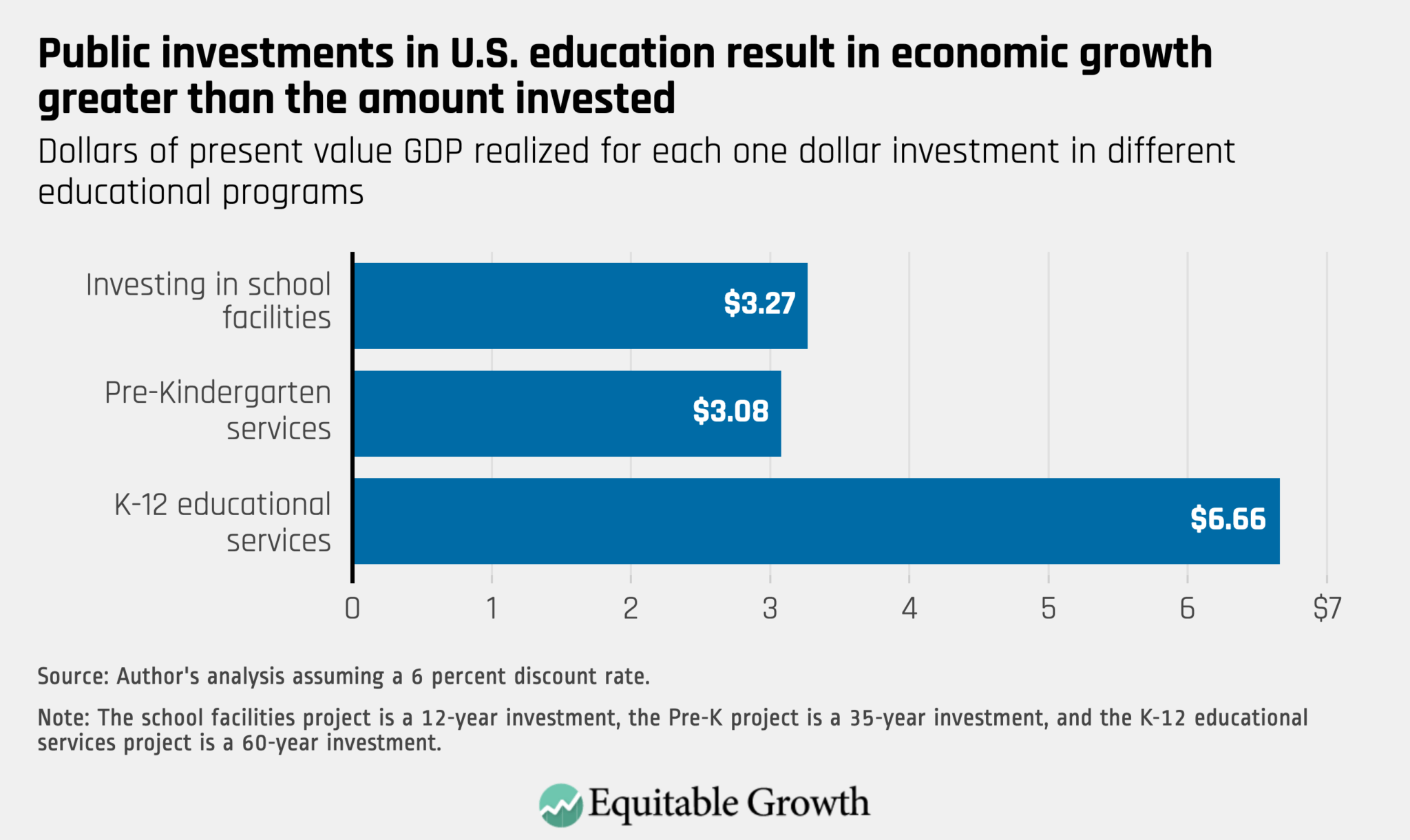

- $200 billion of investments in universal pre-kindergarten. Academic research finds that pre-K programs can spur growth, create jobs, and ultimately pay for themselves. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

- A four-year extension of the enhanced Child Tax Credit that was included in the American Rescue Plan enacted in March. Sometimes described as a "child allowance," the evidence shows that this policy would pay dividends not just for low- and middle-income families, but the economy as a whole.

- The use of automatic triggers, based on economic conditions, to extend the length and amount of Unemployment Insurance benefits, some of which are currently scheduled to expire in September. The plan does not outline a vision for revamping the Unemployment Insurance program writ large, but ensuring that program enhancements turn on and off based on objective economic indicators rather than arbitrary and politically-negotiated dates is a major step in the right direction.

- The United States has the fiscal space to finance these investments with deficits, but President Biden proposes to finance this package with taxes on the income and wealth of the richest Americans. The top 1 percent of income earners now enjoy the fruits of a historically outsized share of the nation's economic growth. The American Families Plan envisions raising the top income tax rate from 37 percent to 39.6 percent for individuals making more than $400,000 a year, equal to the top marginal rate in 1997 (and for much of the 1990s and between 2013 and 2017).

In the United States, wealth is even more inequitably distributed than income, so the American Families Plan wisely proposes to raise revenue by taxing the investment income from capital gains of Americans making more than $1 million per year. This would equalize the rates paid by people who earn income through work and those who earn it from investments. Raising revenue from the rich in this way could raise even more revenue than traditional estimates assume, especially because it proposes to end a loophole called "stepped-up basis," which allows some capital gains to never be taxed at all.

The proposal also includes new enforcement resources for the IRS, which will allow the federal agency to target tax evaders in the top 1 percent of income earners, who research shows hide 20 percent of their income from tax collectors.

Conclusion

The top fiscal policy priority for U.S. policymakers should be to make long-overdue public investments in physical and human infrastructure, which evidence shows will pay long-term dividends in the form of strong, stable, and broadly shared economic growth. These investments should be focused on the areas that are most holding back the U.S. economy—and that were so exposed by the coronavirus pandemic—namely combating racial discrimination and injustice, mitigating the effects of climate change, empowering workers, and expanding social insurance protections. The key elements of the American Jobs Plan and American Families Plan, as described by President Biden in his joint address to Congress last night, would represent a huge step toward those goals.

Attention now turns to Congress, which must work with the administration to fill in the details and craft legislation that can pass both chambers. Some concerns raised by some members of Congress, such as those around deficits and economic "overheating," are not well-founded and should not stand in the way of action. But there remain legitimate questions about which elements of the president's plans should be included or excised, and which policies that were left out by the president—such as instituting mark-to-market capital gains taxation, cancelling student loan debt, and improving the way we measure the economy—should be added back in by Congress.

In answering these questions, our hope is that policymakers follow the compilation of academic evidence that Equitable Growth and others have assembled and capitalize on this opportunity to make structural economic change that spurs strong, stable, and broad-based growth.

The post The evidence behind Biden's big plans for rebuilding infrastructure, reducing poverty, and combating inequality appeared first on Equitable Growth.

-- via my feedly newsfeed