https://www.epi.org/blog/congress-has-failed-to-extend-additional-unemployment-benefits-as-millions-of-workers-across-the-country-file-new-ui-claims/

The U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) released the most recent unemployment insurance (UI) claims data last Thursday, showing that another 2.3 million people filed for UI benefits during the week ending July 18. Huge swaths of workers in every state are relying on UI for food, rent, and basic necessities. There are 14 million more unemployed workers than jobs. In the face of this economic crisis, Congress has let the extra $600 in weekly UI benefits expire, and now Senate Republicans are proposing reducing the increase to $200, which would cause such a huge drop in spending that it would cost 3.4 million jobs. These benefit cuts will directly harm the workers and their families who need these benefits to weather the pandemic and will cause further economic harm over the next year.

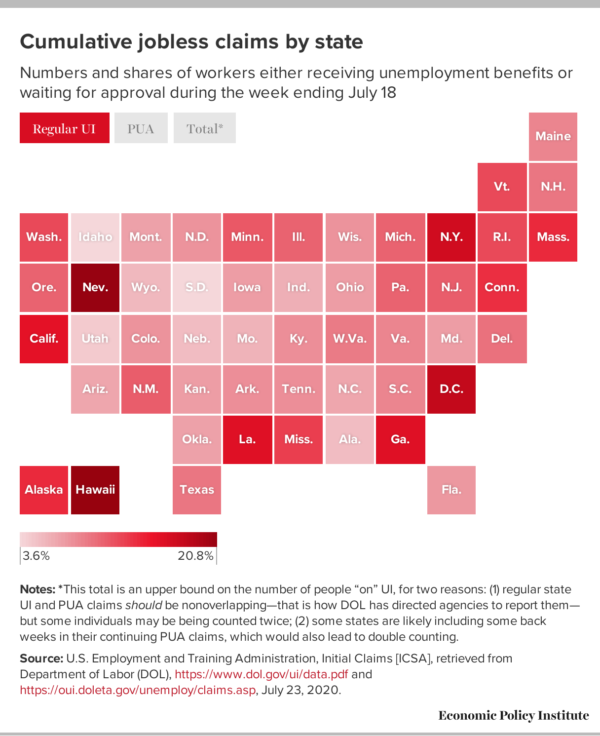

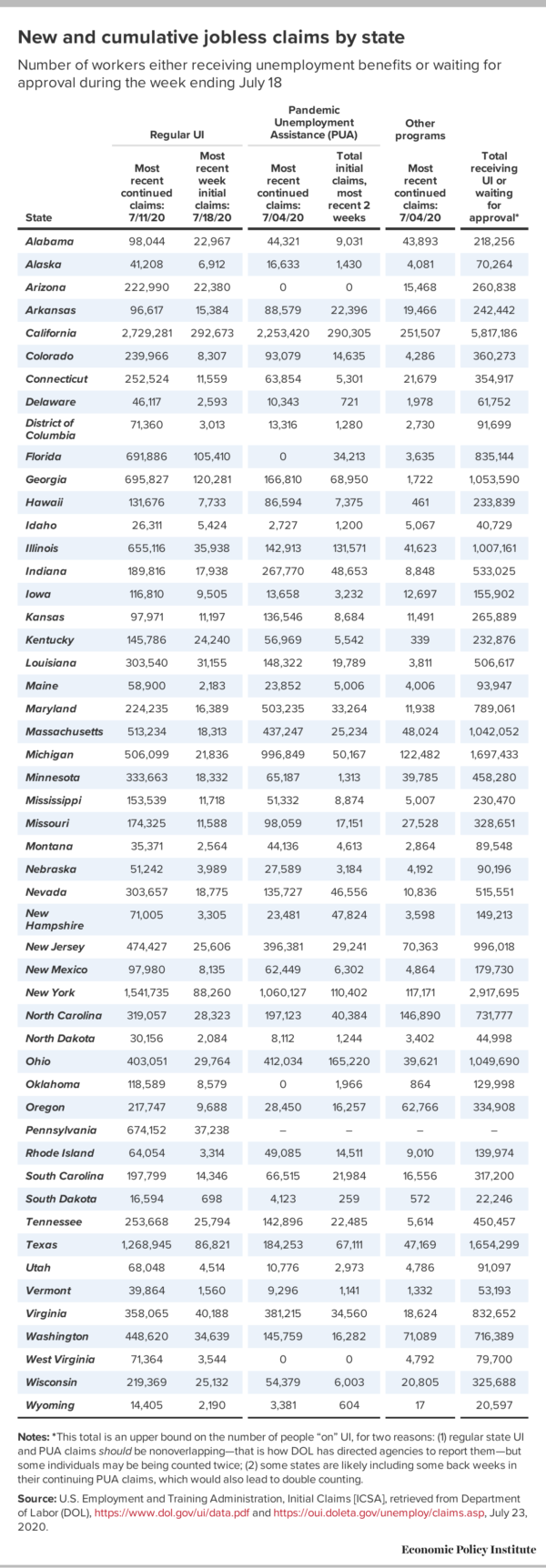

Figure A shows the share of workers in each state who either made it through at least the first round of state UI processing (these are known as "continued" claims) or filed initial UI claims in the following weeks. The map includes separate totals for regular UI and Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA), the new program for workers who aren't eligible for regular UI, such as gig workers.

The map also includes an estimated "grand total," which includes other programs such as Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC) and Short-Time Compensation (STC). The vast majority of states are reporting that more than one in 10 workers are claiming UI. Thirteen states and the District of Columbia report that more than one in five of their pre-pandemic labor force is now claiming UI under any of these programs. The components of this total are listed in Table 1.1

Three states had more than 1 million workers either receiving regular UI benefits or waiting for their claim to be approved: California (3.0 million), New York (1.6 million), and Texas (1.4 million). Seven additional states had more than half a million workers receiving or awaiting benefits.

While the largest U.S. states unsurprisingly have the highest numbers of UI claimants, some smaller states have larger shares of the workforce filing for unemployment. Figure A also displays the numbers of workers in each state who are receiving or waiting for regular UI benefits as a share of the pre-pandemic labor force in February 2020. In six states and the District of Columbia, more than one in seven workers are receiving regular UI benefits or waiting on their claim to be approved: Hawaii (20.8%), Nevada (20.7%), the District of Columbia (17.9%), New York (17.1%), Louisiana (15.9%), Georgia (15.8%), and California (15.5%).

Eight states reported that more than one in ten workers are currently claiming PUA, underscoring the importance of extending benefits to those who would otherwise not have been eligible: Michigan (21.2%), Maryland (16.4%), Hawaii (14.0%), California (13.0%), New York (12.3%), Massachusetts (12.1%), Nevada (11.7%), and Rhode Island (11.4%). Pennsylvania reported that 3.8 million workers have claimed PUA, but that would constitute nearly 60% of the state's workforce, so this is almost definitely misreporting. Arizona did not report any continuing PUA claims for the week ending July 4, which is also likely misreporting since they had reported 2.3 million for the prior week.

As we look at the aggregate measures of economic harm, it is also important to remember that this recession is deepening racial inequalities. Black communities are suffering more from this pandemic—both physically and economically—as a result of, and in addition to, systemic racism and violence. Both Black and Hispanic workers are more likely than white workers to be worried about exposure to the coronavirus at work and bringing it home to their families. These communities, and Black women in particular, should be centered in policy solutions. Cutting off the $600 UI benefit will deepen existing racial inequalities, since Black and Hispanic workers have higher unemployment rates than white workers.

In addition to extending the additional weekly $600 benefit that they have allowed to expire, which will help workers in the immediate term and support millions of jobs, Congress should provide substantial aid to state and local governments. Without this aid, a prolonged depression is inevitable, especially if state and local governments make the same budget and employment cuts that slowed the recovery after the Great Recession. More than five million workers would likely lose their jobs by the end of 2021, harming women and Black workers in particular since they are disproportionately likely to work for state and local governments.

We should despair for the millions who have lost their jobs and for their families, and our top priority as a country should be protecting the health and safety of workers and our broader communities by paying workers to stay home when possible, whether that means working from home some or all of the time, using paid leave, or claiming UI benefits. When workers are providing absolutely essential services, they must have access to adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) and paid sick leave. The current spike in coronavirus cases across the country—and subsequent re-shuttering of certain businesses—show the devastating costs of reopening the economy prematurely.

Enjoyed this post? Sign up for the Economic Policy Institute's newsletter so you never miss our research and insights on ways to make the economy work better for everyone.

Notes

1. That total is really more of an upper bound, and you should exercise caution when interpreting it for three reasons: (1) It includes initial claims, which represent people who have not yet made it through the first round of processing; (2) Some individuals may be being counted twice. Regular state UI and PUA claims should not be overlapping—that is how DOL has directed state agencies to report them—but some states may be misreporting; (3) Some states are likely including some back weeks in their continuing PUA claims, which would also lead to double counting (the discussion around Figure 3 in this paper covers this issue well). Those limitations are the reason that we have so far hesitated to publish this estimate of total claims by state. DOL has worked to overcome misreporting issues and has had enough success that we are now comfortable enough to report the totals here. However, it is clear that there is still some misreporting. Unless otherwise noted, all numbers are as reported by DOL. In this post, I drop the reported PUA (and total) claims for Pennsylvania from the figure and table, since they reported more than 3 million PUA claims to DOL (more than half of their labor force!) despite their Office of Unemployment Compensation reporting that they have only received 1.5 million PUA claims.

-- via my feedly newsfeed