from Yves Smith, my favorite quasi-Trotskyite economist -- a compelling and dismal summary of the combined COVID and economic bad news.

Perhaps it was last week's continuation of bad unemployment figures combined with the recognition that PPP employment-maintenance requires were rolling off and more layoffs are likely. Maybe it was Delta saying it was cancelling half the flights it had planned to add in August. Maybe it's the severity of the coronavirus surges. Who knows what the trigger was, or whether it's just the accumulation of evidence, but big businessmen, who are required to project optimism, are more and more sending downbeat messages about where the economy is going.

It's becoming clear that understanding where the economy is going now depends on understanding where Covid-19 is going. The evidence from the lockdowns was that activity and spending fell before governments intervened. And the contraction was most pronounced in wealthy neighborhoods, even though the blow fell on the less-well-off who commuted in to work there. Those who have the luxury of being able to curtail their activities are largely doing so. Look at big cities. Large companies are overwhelmingly continuing work at home where they can. Business travel is dead; business hotels in NYC like the Four Seasons, the Grand Hyatt, and the Hilton on 6th Avenues are closed.

We though the initial recovery would peter out and turn into at best stagnation and more likely further decay, on the assumption of entire sectors not participating much if at all in a rebound (live entertainment, business travel, tourism, elective surgeries, restaurants) plus Covid-19 being likely to rebound in the fall. With Covid-19 infections rising in nearly all states, the situation is even worse than we'd anticipated.

Most of the issues we'll discuss below are familiar to reader, but there's value in putting them together and seeing where they lead. First to the disease, then to the economic implications.

Disease Progress

It's not news that the infection is spiraling out of control over much of the US. From the Washington Post:

Sunday marked the 41st straight day that the seven-day average for new daily coronavirus infections in the United States trended upward….

Here are some significant developments:

- Kentucky, Louisiana, Oregon and South Carolina all set new single-day records on Sunday, contributing to a nationwide tally of 64,650 new known cases. Idaho, Nebraska, Iowa and five other states have seen their seven-day average for daily new fatalities rise by more than 40 percent in the past week.

- More than 100 Florida hospitals have run out of ICU beds for adults.

More color from Gavyn Davies at the Financial Times:

Fulcrum economists have developed a new model which tracks the epidemic on a state-by-state basis, based on the now-familiar SIRD model used by the Imperial College Covid-19 response team and other researchers.

It suggests that the virus's effective reproduction number, known as R, is now above the critical level of 1 in all but five of the US's 50 states. Weighted by gross domestic product, this means that 95 per cent of the US economy is affected by a viral reproduction rate high enough to cause an exponential rise in the number of cases — unless something intervenes to prevent this. Other researchers have found similar results.

This spread of R levels above 1 is the broadest it has been since the epidemic started. In March, absolute levels of R were higher in the north east, when the reproduction rate exceeded 3 for several weeks and infection numbers doubled every few days.

This is bad enough, but the situation is made much worse with the widespread inability to get Covid-19 test results on a timely basis. The US has a duopoly in medical labs. Quest has said Covid-19 tests will have a reporting delay of 7 days. Labcorp has not been as specific but has 'fessed up to its turnaround time for Covid-19 tests now being 1-2 days longer.

This matters because delays this long neutralize what little disease containment the US had. Early studies found the median time from exposure to showing symptoms is a bit over 5 days. Peak viral shedding appears to occur shortly before or at symptom onset. From what I can tell, people who have tested positive do tell family members and co-workers and others close to them, and those people usually do self-quarantine as best they can. Too late test results means this informal contact tracing is useless.

Some are pointing to the much slower rise in death rates to argue that rising alarm is overdone. The worrywarts have the better case. First, as we saw in the initial surge, deaths are a lagging indicator. As infections continue to rise, the increase in deaths comes 2-4 weeks late. Second, it is true that the infections this time are hitting much younger people, and even though a higher proportion of hospitalizations now are of those under 50 than before, and they aren't requiring ventilators as often, higher survival rates aren't the full story. Covid-19 cases serious enough to require hospitalization regularly produce long-term damage to the lungs, heart, kidneys, and brain.

Even young adults are becoming more vulnerable. From UCSF:

Data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), not included in the UCSF study, indicates that while patients over 65 are significantly more likely to be hospitalized than younger people, the gap is narrowing. For the week ending April 18, there were 8.7 hospitalizations per 100,000 of the population for the 18-to-29 age bracket, compared with 128.3 per 100,000 of the population for patients over 65. By the week ending June 27, the figures were 34.7 and 306.7 respectively, representing a 299 percent increase in hospitalizations for young adults, versus a 139 percent increase in hospitalizations for older adults.

Things are almost certain to get worse on the disease front before they get better. Atlanta's and Houston's mayors are fighting with their state governors to reimpose restrictions. More and more cities and states are implementing mask requirements but enforcement is toothless, plus defiance and poor compliance are high. Even among my mothers' aides who are Certified Nursing Aide, about half wear their masks below their noses and pull them down when talking. If people with basic medical training who are around old people aren't masking up properly, how many are? When I am out, I see 20% to 25% with their masks below their noses or chins.

Even with church attendance down, some have retreated from in-person services due to reports of churches generating infection clusters. But nearly half are still holding services in person. The row over whether to reopen public schools is underway. Given the institutional inability to impose enough safety measures like student mask-wearing, plexiglass barriers around desks and lunchroom seats, and regular cleaning, most teachers and some parents are opposed. But there's enough ideological and business pressure to make it likely that schools will reopen in most jurisdictions, even if not in big cities. This is pretty sure to produce more infections in those ares.

University and college reopenings will provide another Covid-19 boost. Even with schools taking precautions, they have no control over what the kids do when outside class. Think they won't go to bars and coffee houses? Go to gyms? Get laid? So the students will frequent pubs and eateries and their staff, who are separately at risk by working in close quarters, are on the front line.

And some of the ones who are back on campus have returned because they are work-study, which will can put them in different settings than they are as students, again offering another transmission route.

In other words, if we don't see a strong change in sentiment by mid August towards aggressive clampdowns, the uptrend could start accelerating in September and October.

And there's no magic solution in sight. Vaccine? At least a year before one would even start being distributed. Dr. Fauci has been dialing down expectations about vaccine efficacy, saying he'd accept 70% to 75% but a level like that in combination with 1/3 of Americans now saying they won't get a Covid-19 vaccine even if it were cheap means the disease will still be with us for quite a while. And that's before getting to the question of how long vaccine or disease-conferred immunity will last.

Economic Impact

The foundations are rotting despite the stimulus-induced appearance of normalcy.1 Evictions are rising in areas with no freezes, the level isn't yet above the old normal. But more tenants are expected to come up short on payments for August than for July, so the level will continue to rise.

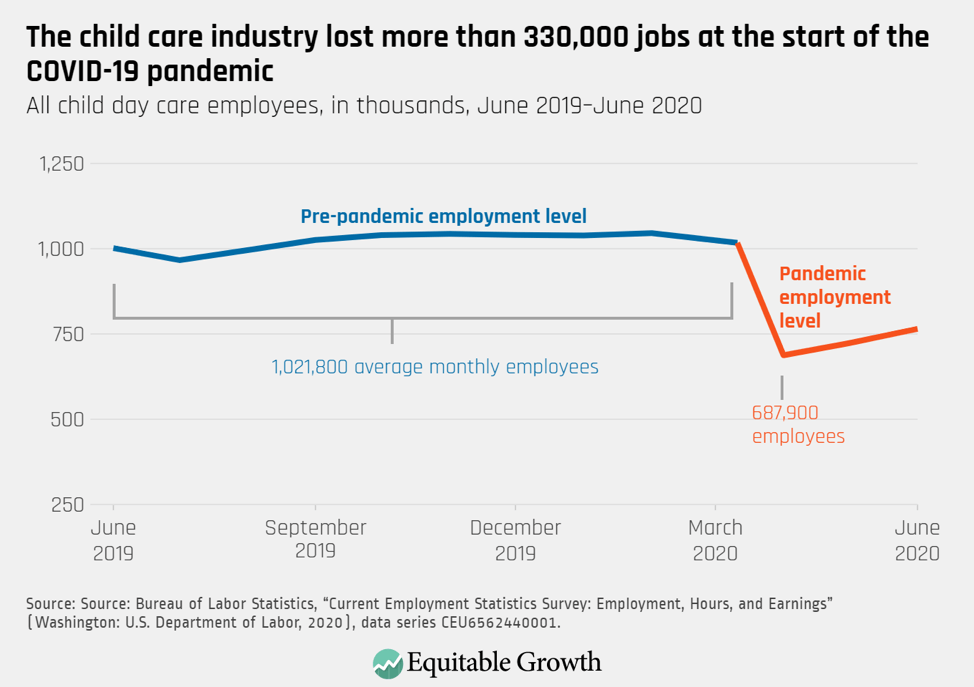

As we alluded to in our intro, the level of joblessness remains high, with hiring close to offset by new job losses. And this is before PPP-induced payroll retention rolls off in a big way. Many small businesses have been hanging on by their fingernails, and the longer Covid-19 is running at high enough levels for many people to curtail their activities, the more will go under.

Another contractionary force that is only staring to kick in are state and local government budget cuts. Absent a change of heart in DC leading to direct grants to states and cities, shortfalls in sales, income, hotel, and gas taxes are already biting. Real estate taxes on commercial properties will follow soon, since large property owners are experienced and aggressive at winning reappraisals when their rent rolls fall.

From the Wall Street Journal's downbeat lead story, U.S. Companies Lose Hope for Quick Rebound From Covid-19. Mind you, this is the perspective from large businesses who are in theory best positioned to ride out a severe downturn:

The fierce resurgence of Covid-19 cases and related business shutdowns are dashing hopes of a quick recovery, prompting businesses from airlines to restaurant chains to again shift their strategies and staffing or ramp up previous plans to do so. They are turning furloughs into permanent layoffs, de-emphasizing their core businesses and downsizing production indefinitely….

Executives who were bracing for a monthslong disruption are now thinking in terms of years. Their job has changed from riding it out to reinventing. Roles once thought core are now an extravagance. Strategies set in the spring are obsolete.

"It's going to be a different game," said Bill George, former CEO of medical-device company Medtronic PLC and a senior fellow at Harvard Business School. Mr. George said many companies now need to explore strategies they might have once deemed unthinkable, from hospital chains embracing a long-term shift to telemedicine to apparel makers figuring out how to market and sell their wares in an environment where many stores don't reopen.

The story described how Delta had cut way back on restoring some flights, along with distress at other carriers, with additional retrenchment anecdotes from Chipotle and Vox Media.

Gavyn Davies offered a supposed worst case scenario:

Fulcrum economists have modelled an alternative scenario where full lockdowns are eventually needed in states where the R is currently above 1.5, with partial lockdowns in states where R lies between 1.25 and 1.5, and no lockdowns elsewhere.

This would lead to a large drop in activity — in effect, a double dip — of about 7 percentage points through the whole economy while the lockdowns last. If the situation persisted for three months, it would knock almost 2 percentage points from this year's growth rate, compared to the latest consensus forecasts.

Even if some areas do go back to lockdowns, our pattern has been to quit too soon. Starting from a higher baseline of infection than before implies a longer period of restriction would be needed. So I am not confident that even a second period of lockdowns would get infections low enough that mask-wearing and contact tracing could keep Covid-19 at a sufficiently low level so that most "old normal" activities would resume and the rest of the world would let Americans visit them again.

The other open question is how much will be approved in the second round of stimulus. I'm not following this one closely given the Democratic Party to ask for little and fold easily. However, the extra $600 a week of unemployment benefits ends on July 26. There is a lot of Republican opposition to extending it since 5 out of 6 were making more than when they were employed, which allegedly made it hard for those businesses who wanted to rehire to get people on board.2 And Democrats also seem to accept the idea there should be fewer checks to individuals, say only to lower income households. Thus despite economic prospects worsening before our eyes, Congress seems stuck with the view of a couple of weeks ago, that the damage will continue for perhaps another quarter, and therefore a smaller stimulus is what the doctor ordered.

The problem is stimulus or no stimulus, absent a miracle treatment for Covid-19 very soon, the US is going to lose more productive capacity: restaurants, salons, hotels, theaters, symphonies, businesses near office buildings and commuter hubs, suppliers to airports and airlines. This is not "job loss" in the normal recession sense, where the main source of position and hours cuts is lowering production and reducing shifts, not permanently closures or shuttering locations.

Even though giving individuals subsidies to enable them to pay rent and keep food on the table is a critically important stopgap, it will shortly be nowhere enough. If positions are permanently destroyed, the answer is direct employment by government, either through block grants to cities and states or Federal programs.3 The US has a tremendous amount of deferred infrastructure maintenance and upgrades as a place to start. But the odds of this Congress and Administration going down this path are about zero. And I don't hold much hope for a Biden Administration having the gumption.

_____

1 Fortunately, I don't have to have it, but I still have not gotten my $1200. I really hate having to spend time chasing it down.

2 A testament to how many employers are either nor or barely paying a living wage.

3 Here is where some will start champing for a UBI. Please don't. Even in the old normal, a UBI high enough to provide enough to live on would be massively inflationary. With productive capacity shrinking, it would be even more so. A UBI at less than a living wage level winds up simply being a wage subsidy for big employers like Walmart and Amazon. Silicon Valley squillionaires who have been backing a UBI too often have let the toad hop out of their mouth: a UBI would allow people with jobs to quit them and work in their "incubators" for free, alleviating them of the need to pay a stipend

-- via my feedly newsfeed