The Pandemic Treaty, Crypto, and Inequality

Dean Baker, via Patreon

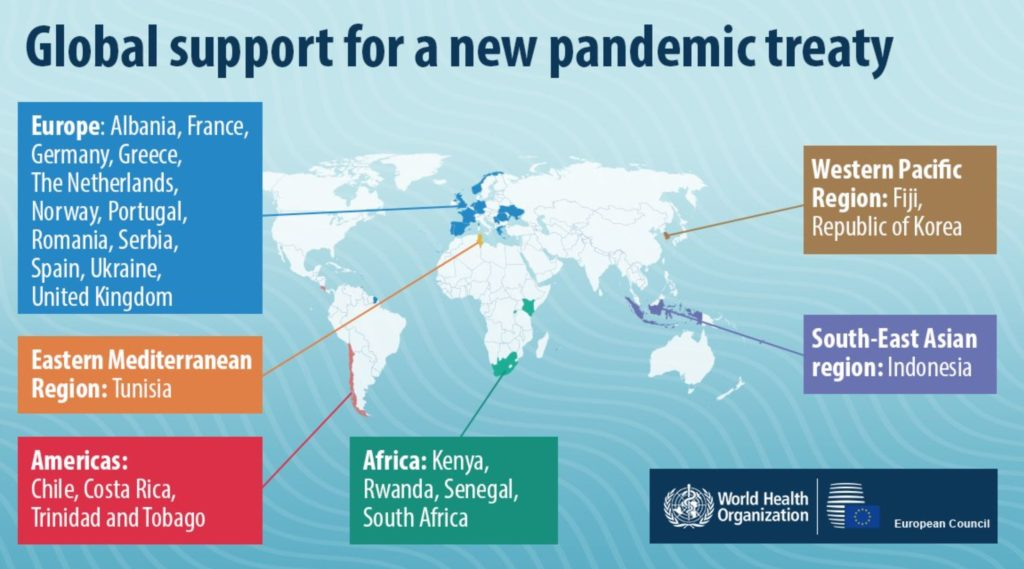

The World Health Organization is in the early phases of putting together an international agreement for dealing with pandemics. The goal is to ensure both that the world is prepared to fend off future pandemics by developing effective vaccines, tests, and treatments; and that these products are widely accessible, including in low-income countries that don’t have large amounts of money available for public health expenditures.

While the drafting of the agreement is still in its early phases, the shape of the main conflicts is already clear. The public health advocates, who want to ensure widespread access to these products, are trying to limit the extent to which patent monopolies and other protections price them out of the reach of developing countries. On the other side, the pharmaceutical industry wants these protections to be as long and as strong as possible, in order to maximize their profits. As Pfizer and Moderna know well, pandemics can be great for business.

The shape of this battle is hardly new. We saw the same story not just in the Covid pandemic, but also in the AIDS pandemic in the 1990s, when millions of people needlessly died in Sub-Saharan Africa because the U.S. and European pharmaceutical industry tried to block widespread distribution of AIDS drugs.

Although the battle lines are familiar, one disturbing feature is the continuing failure of those concerned about inequality to take part in this debate. In the United States, we have plenty of groups and individuals who will spend endless hours fighting over clauses in the tax code that may give a few hundred million dollars to the rich. This is generally a good fight, but it is hard to understand the lack of interest in the structuring of a pandemic treaty that could mean hundreds of billions of dollars going to the rich.

This is not fanciful speculation. After the U.S. government paid Moderna $450 million to develop its Covid vaccine, and then another $450 million for the Phase 3 clinical trials, it then let the company have intellectual property rights in the vaccine. The stock price then increased more than ten-fold, creating at least five Moderna billionaires.

The extent of government support for the Moderna vaccine is extraordinary, but the basic story of drug companies getting huge profits, and select employees getting very rich, as a result of government research and government-granted patent monopolies, is very much the norm. The United States will pay close to $525 billion for prescription drugs in 2022.[1]It would likely be paying less than $100 billion in a free market, without patent monopolies and other forms of protection. The difference of $425 billion is more than half the size of the defense budget, it comes to more than $3,000 per family. And, it makes a relatively small number of people very rich.

The issue of intellectual property claims in the context of a pandemic preparedness agreement will not directly overturn the whole structure of the pharmaceutical industry, but it is likely to involve a substantial chunk of money, if a future pandemic is similar to the Covid pandemic. It also could establish an alternative path for financing drug development.

If there was an agreement that publicly funded research would be freely shared across countries, and that anyone with the manufacturing capabilities could produce the drugs, vaccines, and tests that were produced by the research, it could establish the feasibility of a clear alternative to patent monopoly financed research. This could become a model for drug development more generally, which would jeopardize the huge fortunes being generated in the pharmaceutical industry.

For this reason, there is potentially an enormous amount of money at stake, with large impacts on inequality, in how a pandemic preparedness agreement is structured. In short, there is plenty here that should warrant the interest of the individuals and organizations that focus on inequality; they should be paying attention.

Of course, this doesn’t take away from the fact that the main focus of a pandemic agreement should be on saving lives. But the delays in sharing technology in the Covid pandemic strongly suggest that the path of open source research and free market production will be best both from the standpoint of reducing inequality and saving lives.

The Crypto Meltdown: Just Tax Gambling

I’ve been following economic debates long enough to have seen lots of craziness. In the 1990s stock bubble, I heard PhD economists telling me that we could count on the stock market going up 10 percent a year, even when price-to-earnings ratios were already at record highs. In the 00s, we had financial experts saying that housing was a safe investment because, even if the price plummeted, you could always live in your home.

The crypto craze has both bubbles beat, as the price of absolutely nothing soared to incredible levels. Other than possibly facilitating illegal transactions (I’ve heard law enforcement experts claim that crypto can now be traced relatively easily), there is no remotely plausible use for crypto. In other words, its price is pure speculation. Bitcoin and other crypto currencies have no intrinsic value, therefore the price can very possibly fall to zero, once the promoters run out of suckers, or “the brave,” as Matt Damon calls them.

Anyhow, this one really should not be hard from a policy standpoint. Putting money in crypto is gambling, pure and simple. We don’t make it illegal for people to gamble. They can gamble in Las Vegas bet on sports events and elections, or play the lottery. We just tax gambling so the government can get a cut and we try to make sure that people understand what they are doing – that they are playing a game that is structured so that they will lose.

In this sense, taxing crypto trades seems like an ideal policy. It will be way to both get tax revenue and also to inform people that they are gambling, not investing. It looks like we presently have around $2 trillion a year in crypto trades. If we tax each trade at 1.0 percent rate (half paid by the buyer and half by the seller), that would raise $20 billion a year, or $200 billion over a ten-year budget window.

A tax of this size (still far lower than taxes on casino gambling or lotteries) would hugely reduce the volume of trading, so the government may end up collecting half this amount, or even less. But, by reducing the resources that are tied up in crypto trading, we will be freeing up resources for productive uses, even if the government is not collecting the money in taxes. Think of it as anti-inflation policy.

The good part of this story is that there really is no downside. When we tax things like food or gas, we make it more difficult for people to buy items that they need to get by. But who cares if it is more expensive for people to speculate with crypto?

The folks who run the crypto exchanges will be unhappy, as well as the celebrities who might get fewer dollars for their ads, but these people can instead try to channel their energy into something that is productive. People make money pushing heroin also, but no one feels bad about reducing opportunities in the heroin industry.

There also is a side benefit from a tax on crypto. It may get people to think more clearly about the financial sector generally. We need a financial sector to carry through transactions and to allocate capital, but we have seen the size of the financial sector explode (relative to the economy) in the last half century. This hugely bloated financial sector is an enormous drain of resources from the economy and a major source of inequality.

A tax on crypto can be a step towards implementing financial transactions taxes more generally. A tax on trades of stocks, bonds, and other assets would have to be far lower, since there would be an economic cost from eliminating these trades altogether. But we could have a tax of, say 0.1 percent on stock trades, which would just raise trading costs back to their 1990s levels. This would eliminate much short-term speculative trading, and could raise close to $100 billion a year.

We are very far from having the political support for a broad financial transactions tax, but perhaps the FTX meltdown can create enough anger to build momentum for a tax on crypto trades. It certainly seems like it’s worth a try.

Can Progressives Learn to be Opportunists?

The pandemic preparedness treaty and the crypto collapse might seem pretty far removed, but both present opportunities to crack down on major sources of waste and inequality in the economy. The right has been very clever in finding ways to undermine progressive structures and sources of power.

For example, they managed to destroy traditional defined benefit pensions by inserting an obscure provision in the tax code, which created 401(k) defined contribution retirement accounts. They hugely undermined manufacturing unions by pursuing fictious “free-trade” agreements, which subjected manufacturing workers to international competition, while protecting high-end professionals and increasing protections for patent and copyright monopolies.

The pandemic agreement provides a great opportunity to weaken patent monopolies and related protections, while increasing the prospect that billions of people in the developing world will be able to survive the next pandemic. The crypto meltdown provides a window through which people may see the enormous waste and corruption in the financial sector. It would be great if progressives could take advantage of these opportunities.

[1]This figure comes from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Income and Product Accounts, Table 2.4.5U Line 121. The calculation of the cost without patent monopolies can be found here.