https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2021/12/20/chile-copper-bottomed/

The victory of former student leader and activist Gabriel Boric in Chile's presidential election is the culmination of a sweeping change of mood and direction among Chilean voters. In a 56% turnout, the highest since voting was made voluntary, 35-year old Boric took 56% of the vote compared to ultra-right Antonio Kast's 44%.

Boric has pledged to stop mining projects that damage the environment, increase taxes on the rich, end private pension schemes and remove student debt. During his victory speech, Boric, who is part of a broad left-wing coalition that includes the Chilean Communist party, said he would oppose mining initiatives that "destroy" the environment. That included the contentious $2.5bn Dominga mining project that was approved this year.

Earlier this year, elections to Chile's Constituent Assembly resulted in a majority for the (disparate) left. The Assembly is supposedly rewriting the Constitution to replace the authoritarian structure of the Pinochet military regime after 40 years. But Chile's Congress (parliament) is split down the middle between right and left coalitions.

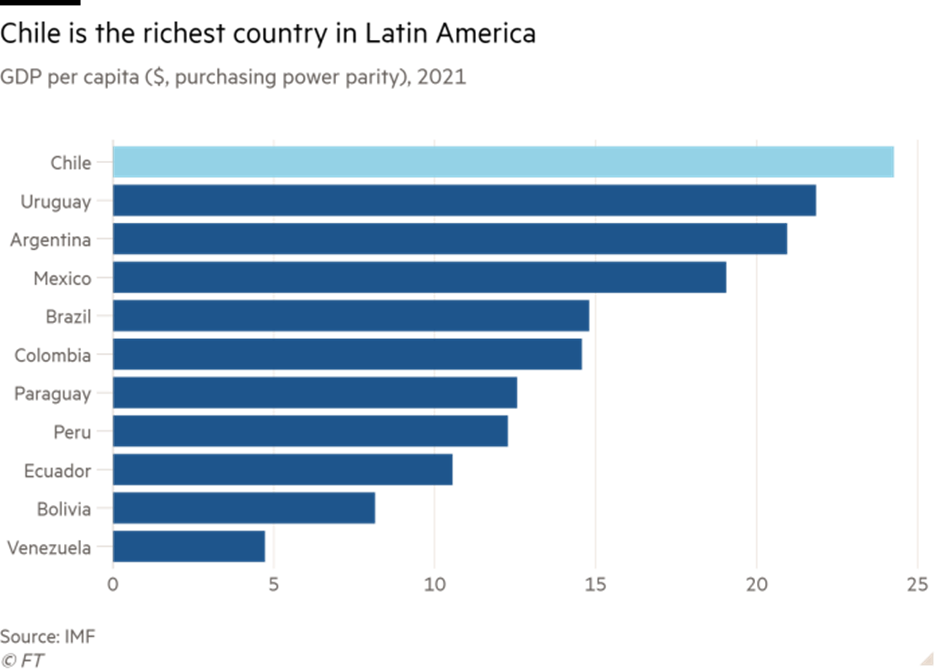

Chile is the richest country in Latin America as measured by GDP per head. But its 20m population makes it tiny compared to Mexico or Brazil, which have populations six to ten times larger and GDPs four to five times larger. Argentina and even Venezuela are much larger in population and GDP.

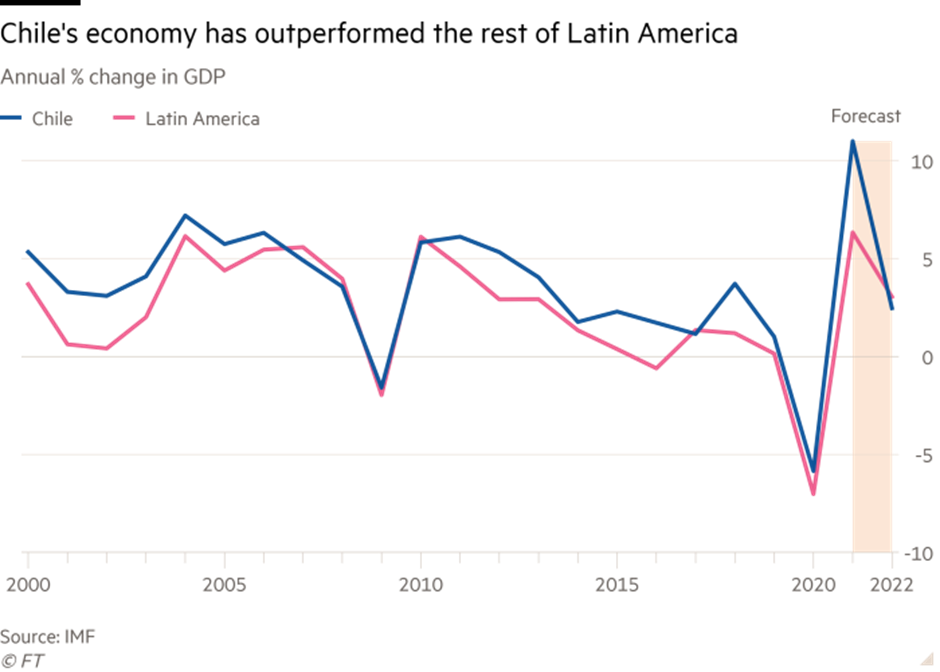

Nevertheless, Chile's real GDP growth rate has generally been slightly faster than the rest of Latin America and its governments have thus been relatively stable. Many mainstream economists and political theorists often use this to claim that Chile is a 'free market' capitalist economic success story and consider Chile as the "Switzerland of the Americas". Chile is a member of the OECD, the rich nations club, and in the (NAFTA-USMCA) trade bloc with Canada, Mexico and the US.

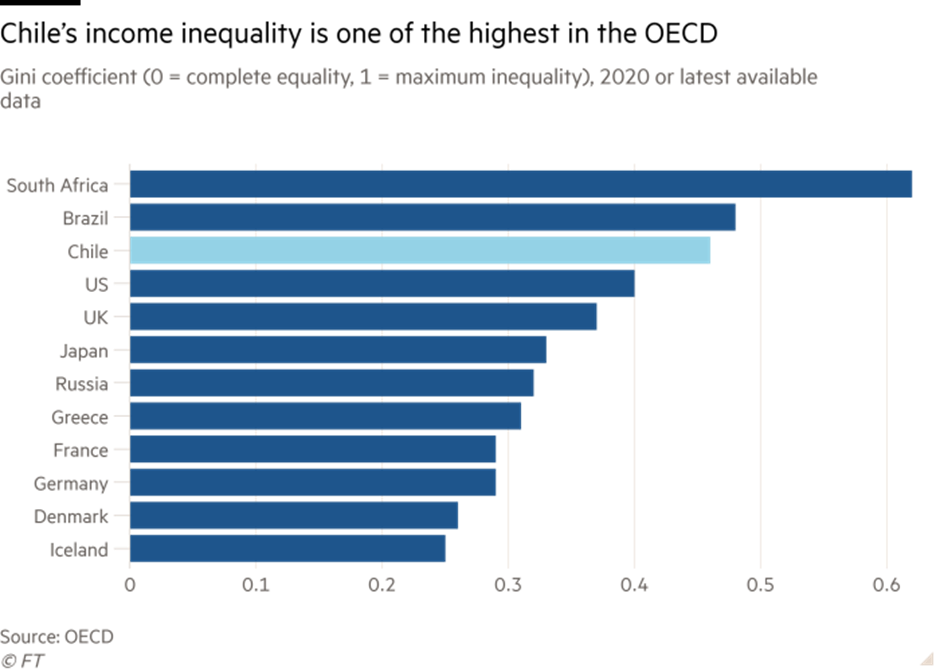

But this apparent success story is only relative in GDP growth compared to other Latin American economies. Moreover, such gains have mainly gone to the rich in Chile. Income inequality is among the worst in the OECD, only surpassed by Brazil and South Africa.

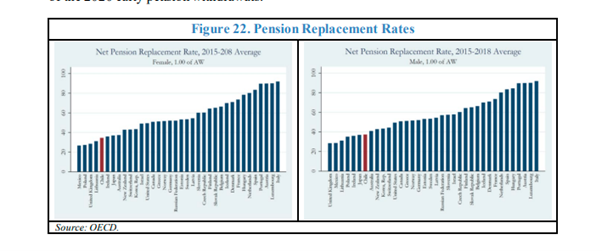

The income share of the bottom decile in Chile is one of the lowest in the world. Only a few countries, largely from Latin America, have lower income share accruing to the bottom decile of the distribution and this share has deteriorated in relative terms in the last 20 years. Social spending (as a share of GDP) in Chile appears higher than in Mexico and Peru. But public services have been reduced, forcing people to use private profit operations. In particular, pensions are dominated by private sector companies and most Chileans find their savings for retirement are just too meagre to fund a decent standard of living in old age.

This was one of the big issues in the election and led to the widespread protests against pro-capitalist policies in 2019 (before COVID) which has now culminated in Boric's election. The IMF found that 'replacement rates' (ie pensions relative to average working income) in Chile are very low relative to other OECD economies, and this deficiency is even more pronounced for females than for males.

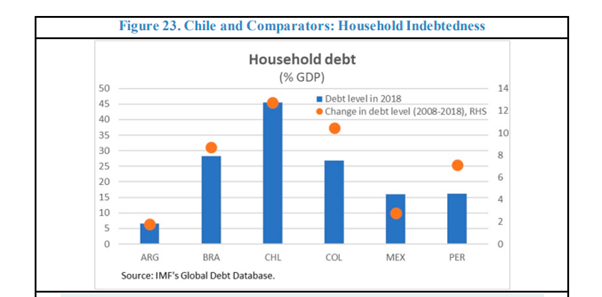

Amid high and rapidly increasing costs of living alongside limited income growth and low pensions, many households have accumulated considerable amounts of debt.

Taxes on the rich are very low, so that income redistribution is lower than almost all OECD peers and many other poor economies.

Chile's relative economic success has always been based on its copper and mineral exports. If copper and mineral prices are high and rising, Chile's economy does better and conversely – but of course, little of that 'trickles' down from the profits of multi-nationals to the average Chilean household.

There have been some Marxist analyses of the Chilean economy that show how the profitability of Chilean capital has been driven by the copper cycle. Diego Polanco in his study for the whole of 20th century noted that "capital accumulation is driven by profitability" and that "the profit rate is a crucial variable for economic growth." Polanco found that and collapse of profitability explained the crisis phases in the Chilean capitalist economy. "While Chile was a surplus labor economy, technical change had favorable contributions to the profit rate. However, once the process of urbanization advanced, Marx-Biased Technical Change took place, having a negative contribution to profitability." The neo-liberal period under Pinochet from the 1970s saw a rise in profitability enabling the regime to maintain its control for decades.

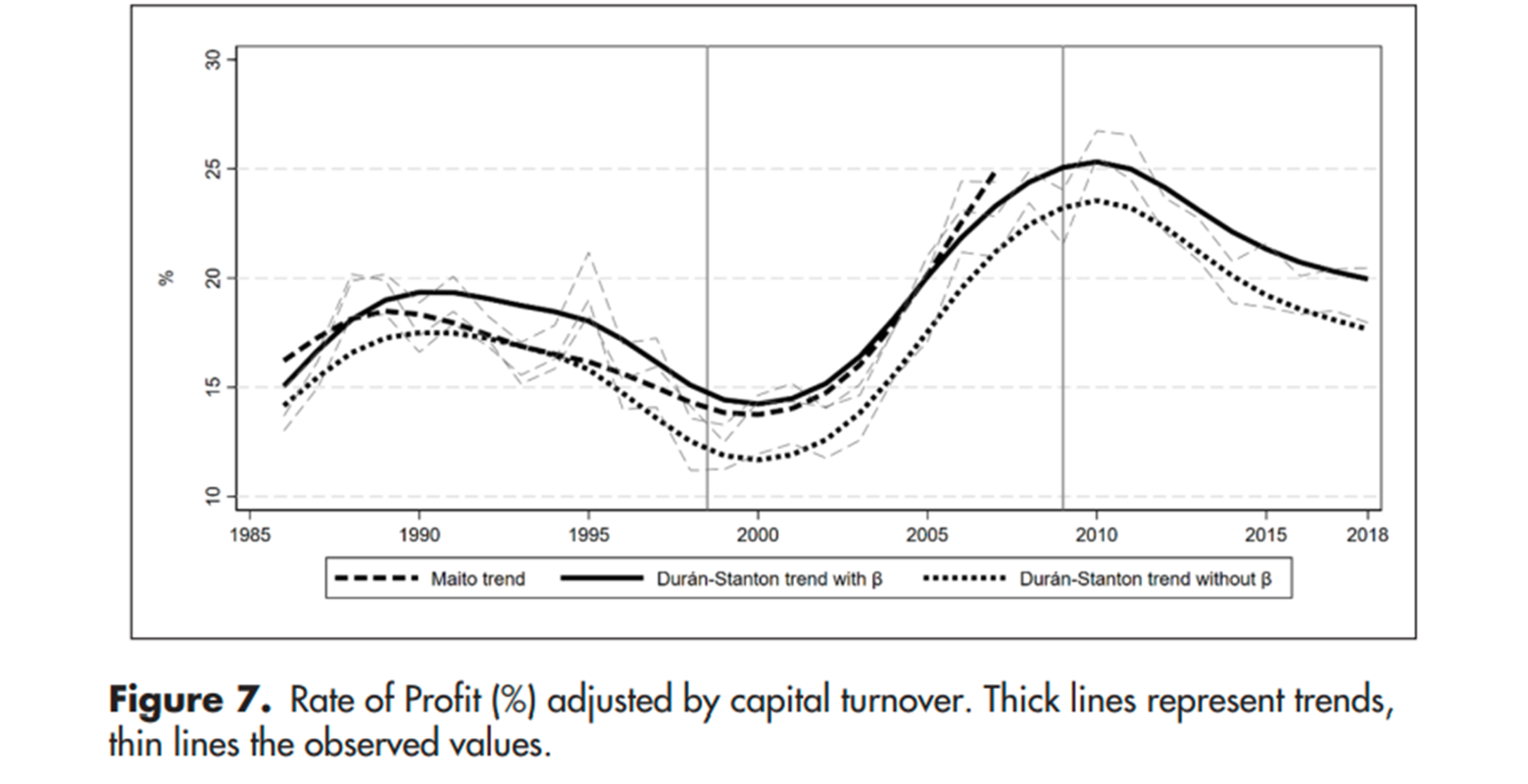

In a more recent study, Gonzalo Duran and Michael Stanton found that the rate of exploitation in Chile's economy rose or fell according to the movement of the copper price. Profitability fell during the 1990s as copper prices stayed low and Marx's law of profitability operated to lower the rate of profit. "In contrast, during the copper super-cycle period of 2004–2009, profits related to wages went up enormously due to the rise in copper prices, but new capital was still imported at low cost and wages were relatively constant. In other words, profits went up relatively to capital and wages and the ROP rose as a consequence."

However, with the end of the commodity price boom from 2010 across Latin America, there was relative economic stagnation and a fall in the ROP.

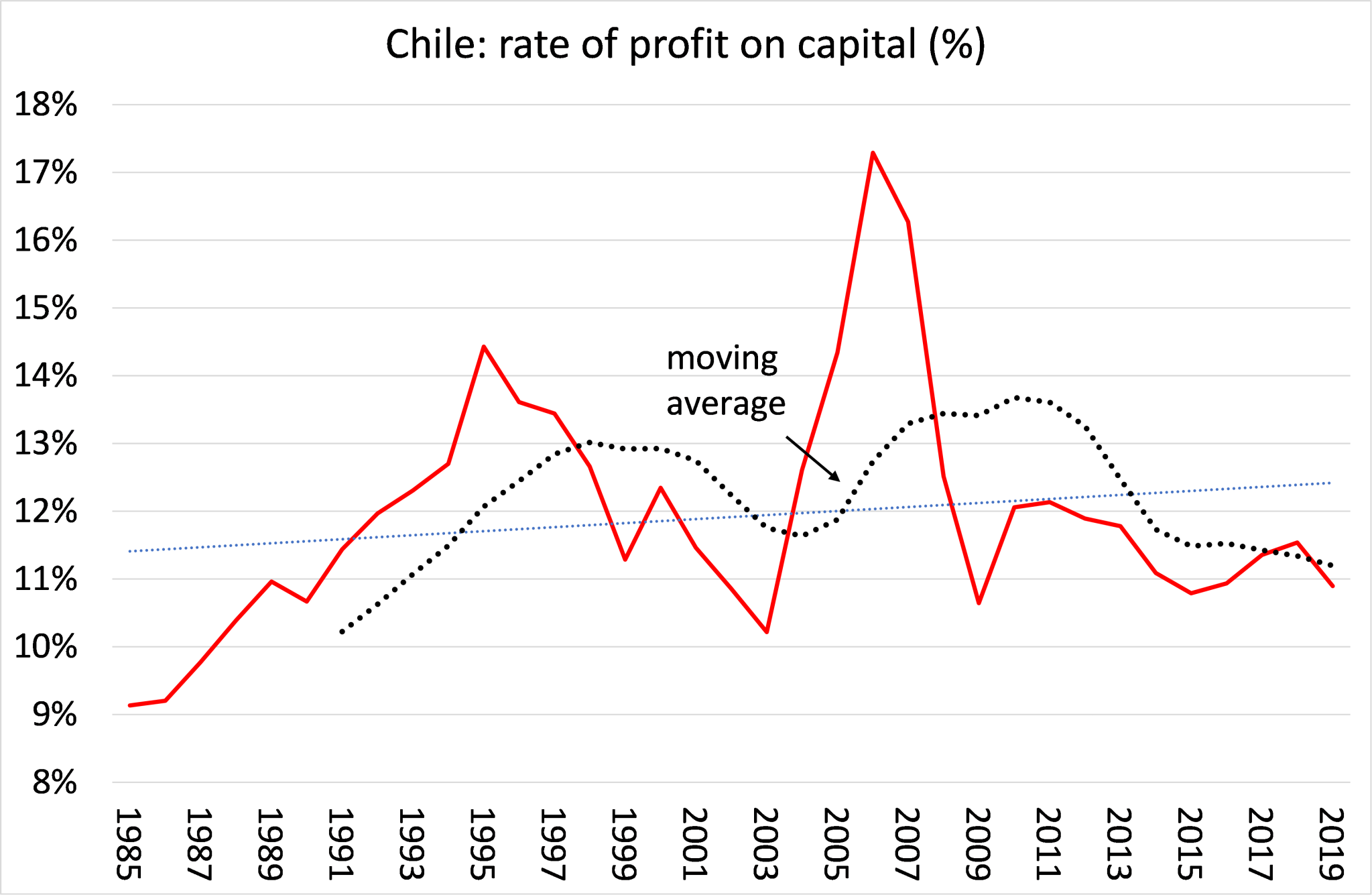

My own measure of Chile's profitability is based on the Penn World Tables IRR series. It delivers a similar trajectory for the profit rate: a drop in the rate from the mid-1990s; then a recovery in the commodity boom from 2003 to 2010, and then with the collapse of commodity prices from 2010, stagnation and decline in profitability.

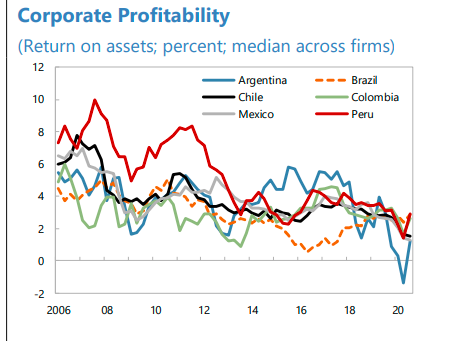

The IMF's own recent measure from 2006 confirms this general trajectory for all Latin American economies after about 2010.

The fall in profitability after 2010 led to slowing growth in GDP, investment, incomes and a further squeezing of public services prior to the COVID slump. With COVID and the health disaster, there was a collapse in the economy, with the main impact falling on those with the lowest incomes and worst jobs. The pro-capitalist forces have been forced into retreat politically.

The victory of Boric could open up a new chapter is Chile's political economy. Indeed, there are huge opportunities for the Chilean economy to increase investment and diversify the economy. The IMF finds that even under the previous regimes there has been some development in non-mineral and technology exports. This must be the way for Chile to go.

So will Boric revive the socialist experiment began by Salvador Allende in the early 1970s? So far, that seems unlikely, as Boric's program is moderate by those standards; with no plans to socialise the economy, but merely to try and redistribute the largesse appropriated by capital somewhat more evenly. The multi-nationals and the forces of the reactionary right-wing in the Chilean business sector, Congress and the media are gearing up for an incessant campaign of attack against the new President.

-- via my feedly newsfeed