Overview

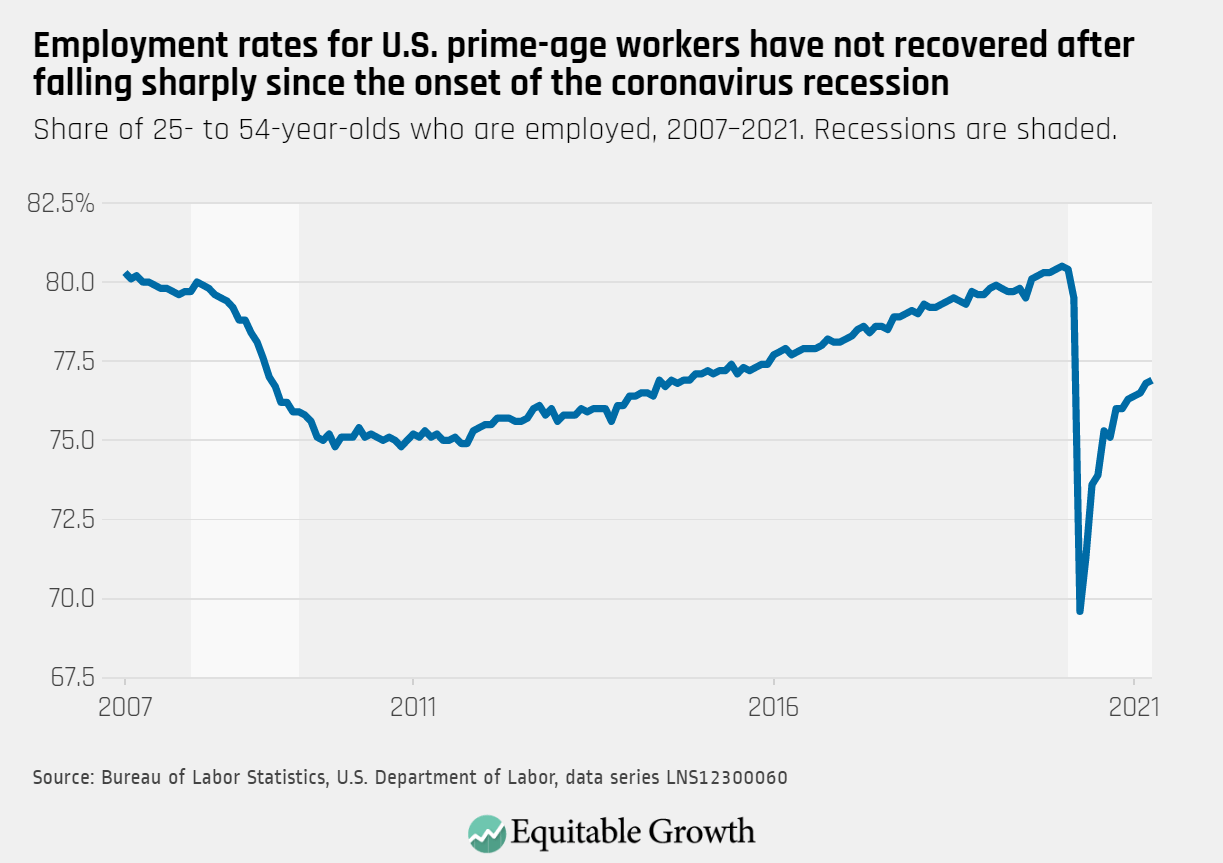

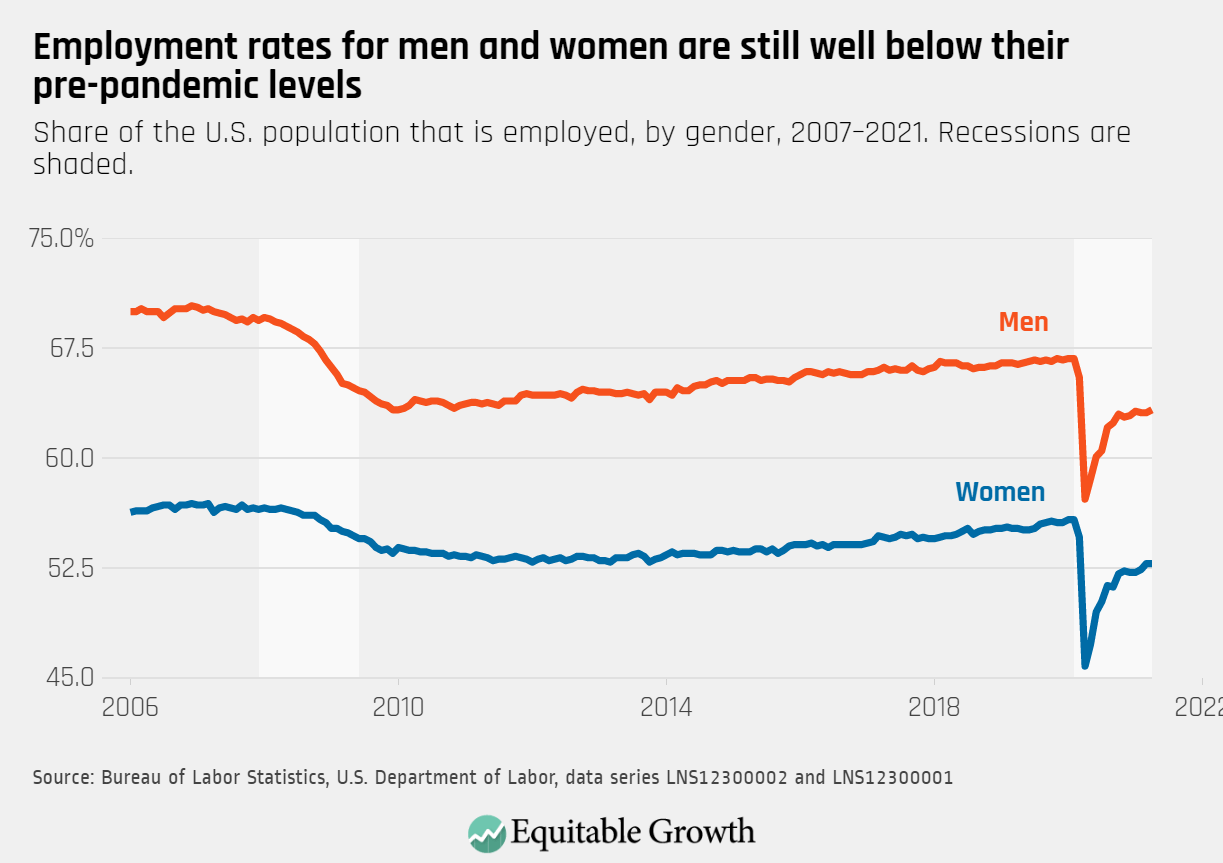

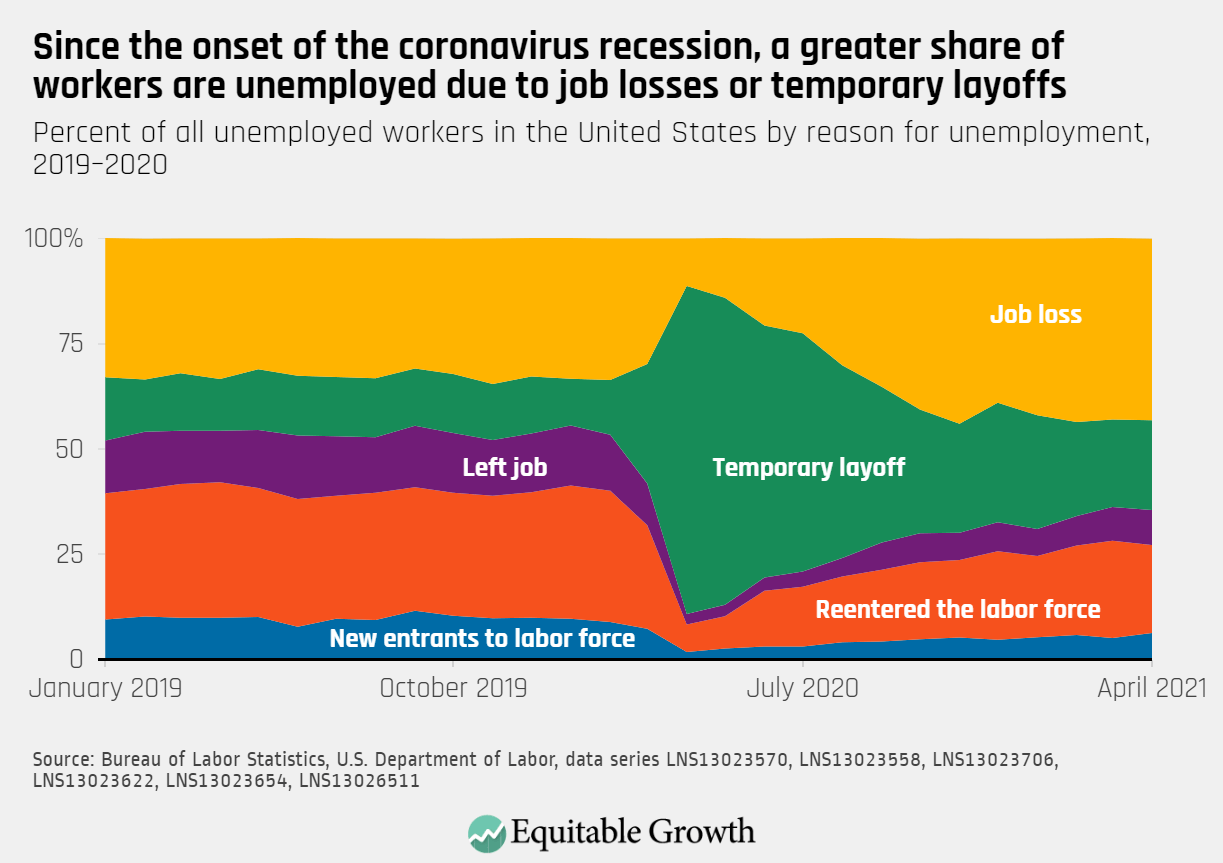

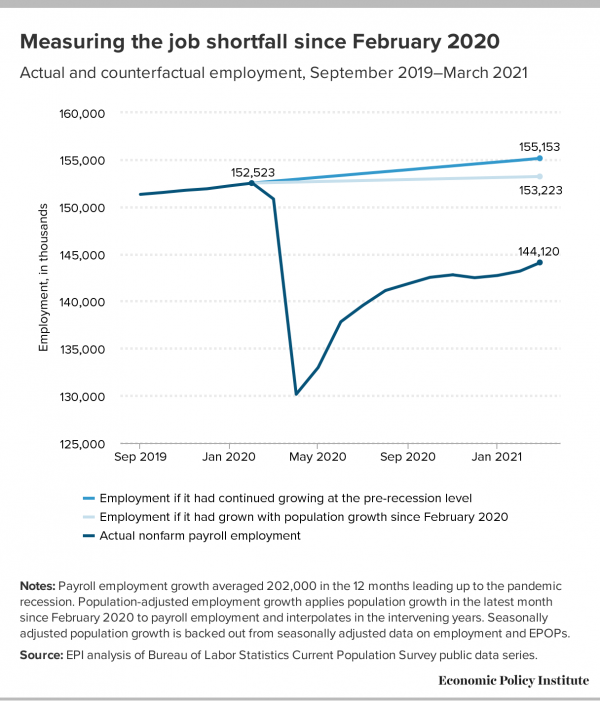

More than a year into the coronavirus recession, unemployment in the United States remains high, and there are 8.4 million fewer jobs than prior to the pandemic. As the U.S. economy begins to recover from the recession caused by this historic public health crisis, some of those who lost their jobs are experiencing what economists refer to as job displacement, where their prior positions no longer exist even as the economy recovers. These workers face unique circumstances when seeking to rejoin the labor force and to reestablish economic security for themselves and their families.

Job displacement is generally understood as a form of job loss that stems from shifting economic and business conditions. For instance, workers can be displaced from their jobs due to a plant closure, a corporate downsizing, insufficient work, or the outsourcing of positions. Job displacement is generally outside of the control of individual workers, but it nonetheless can break down career ladders, dissolve valuable worker-employer relationships, and widen existing racial disparities in labor market outcomes because the research shows that workers of color, and especially Black workers, are most often first in line when job displacement occurs.

All of these consequences of job displacement lead to deep and persistent harmful effects for those who experience it and cause damage to the entire U.S. economy. This issue brief reviews the academic literature on job displacement and offers labor market policies that could help mitigate the negative effects of job displacement. We examine each of the following:

- The long-lasting effects of job displacement

- The especially severe labor market outcomes for workers who are displaced during recessions

- The higher likelihood of severe job displacement for workers of color, and particularly for Black workers

- The effects of job displacement rippling through the entire economy

We then close with several policy ideas that could prevent and mitigate the negative consequences of job displacement. Among these policies are ramping up Short-Time Compensation for workers who work for firms that reduce their hours without displacing them, extending Unemployment Insurance to enable displaced workers to find better job matches, and making it easier for workers to organize and join unions.

The consequences of job displacement are long-lasting

Since the early 1990s, researchers have used administrative data to track displaced workers' job market trajectories through time, finding that post-displacement earnings losses are substantial, experienced across a variety of economic sectors, and persist even after reemployment. Using Social Security records, for example, a team of economists analyzed the earnings and employment trajectories of men who were separated from their jobs as their employers underwent mass layoff events in the early 1980s. They find that those displaced workers experienced initial earnings losses of 30 percent, relative to workers who remained attached to their jobs in the same firms. After 15 to 20 years, the displaced workers continued to have earnings 20 percent below those of their nondisplaced counterparts.

Then, there is the more recent research by Marta Lachowska of the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, Alexandre Mas of Princeton University, and Stephen Woodbury of Michigan State University. They use linked employee-employer data from administrative records to examine how displacement between 2008 and 2010 affected workers' short- and long-term earnings. They find that in the first few months after the loss of long-tenure jobs, workers' earnings were nearly half of what they were prior to displacement. After 5 years, workers' earnings were, on average, still 15 percent below their pre-displacement earnings.

What is driving these earnings losses after job displacement? The team of economists finds that most of the decline in earnings can be attributed to the dissolution of valuable worker-employer relationships. For those displaced from a long-tenure position, the disintegration of good job-worker matches explains a greater chunk of the long-term earnings decline than other factors, such as lost seniority, the erosion of their so-called human capital, or the possibility of transitioning to a lower-paying employer.

In addition, the consequences of this form of involuntary job loss go beyond the loss of earnings. Evidence shows that workers who experience displacement go on to hold jobs with less occupational status, diminished job authority, and fewer employer-provided benefits than otherwise-similar workers who were not displaced.

Workers who are displaced during recessions face especially tough labor market outcomes

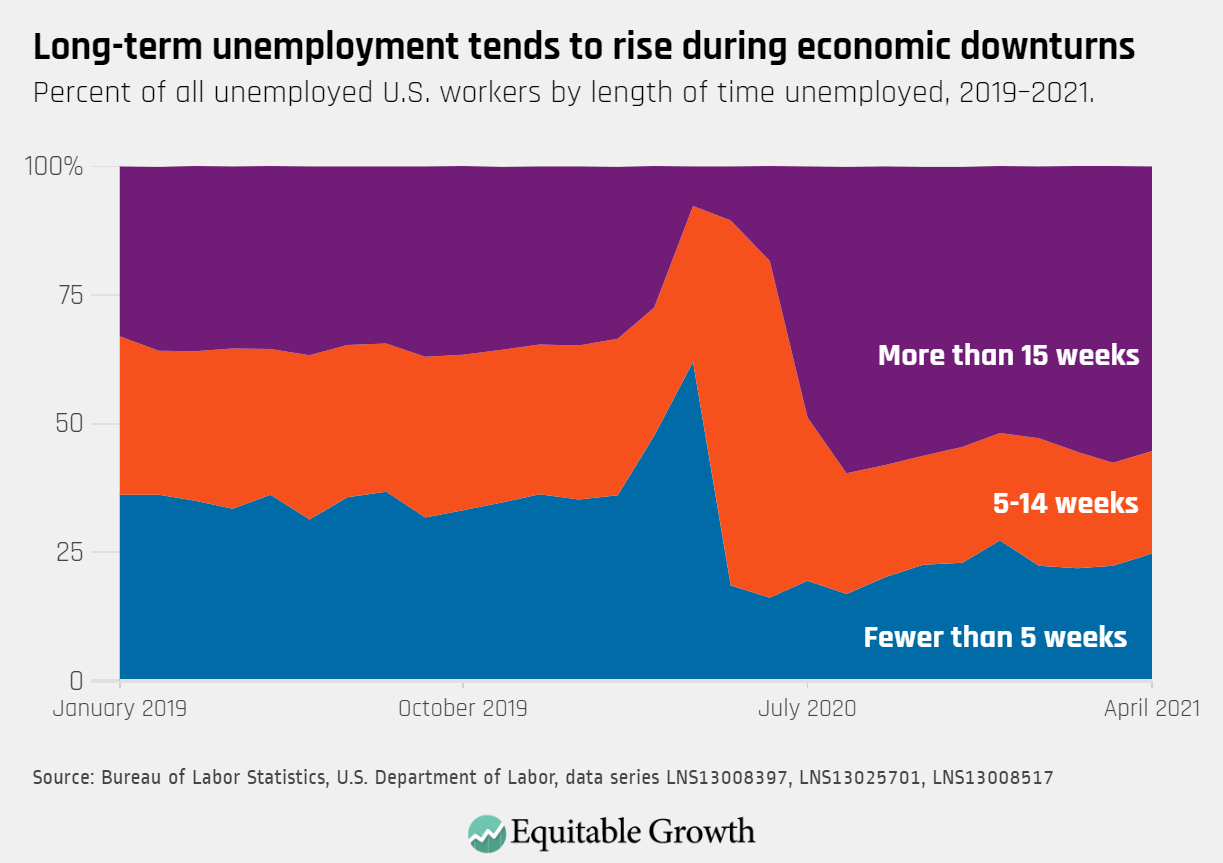

Recessions are especially bad times to lose a job. During economic downturns, employers tend to hire fewer workers, offer lower wages, and increase posted requirements for a given position. When unemployment rates are high, job-seekers have to compete with more workers, employment is harder to find, and workers are more likely to go through long spells of unemployment.

Consequently, researchers find that the negative consequences of job displacement are even more severe when experienced amid an economic slump. For instance, Steven Davis at the University of Chicago's Booth School of Business and Till von Wachter at the University of California, Los Angeles find that men who were displaced when the U.S. unemployment rate was higher than 8 percent experienced earnings losses twice as large as those who were displaced when the overall unemployment rate was lower than 6 percent.

Deeper economic contractions can therefore lead to even worse labor market outcomes for U.S. workers. When studying the Great Recession, for example, Henry Farber of Princeton University finds that the rate of job loss, the difficulty of finding new employment, and the probability of finding only part-time work were all higher in the 2007–2009 crisis than in the economic contractions of the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s. The labor market consequences of job loss, Farber finds, were unusually severe and long-lasting.

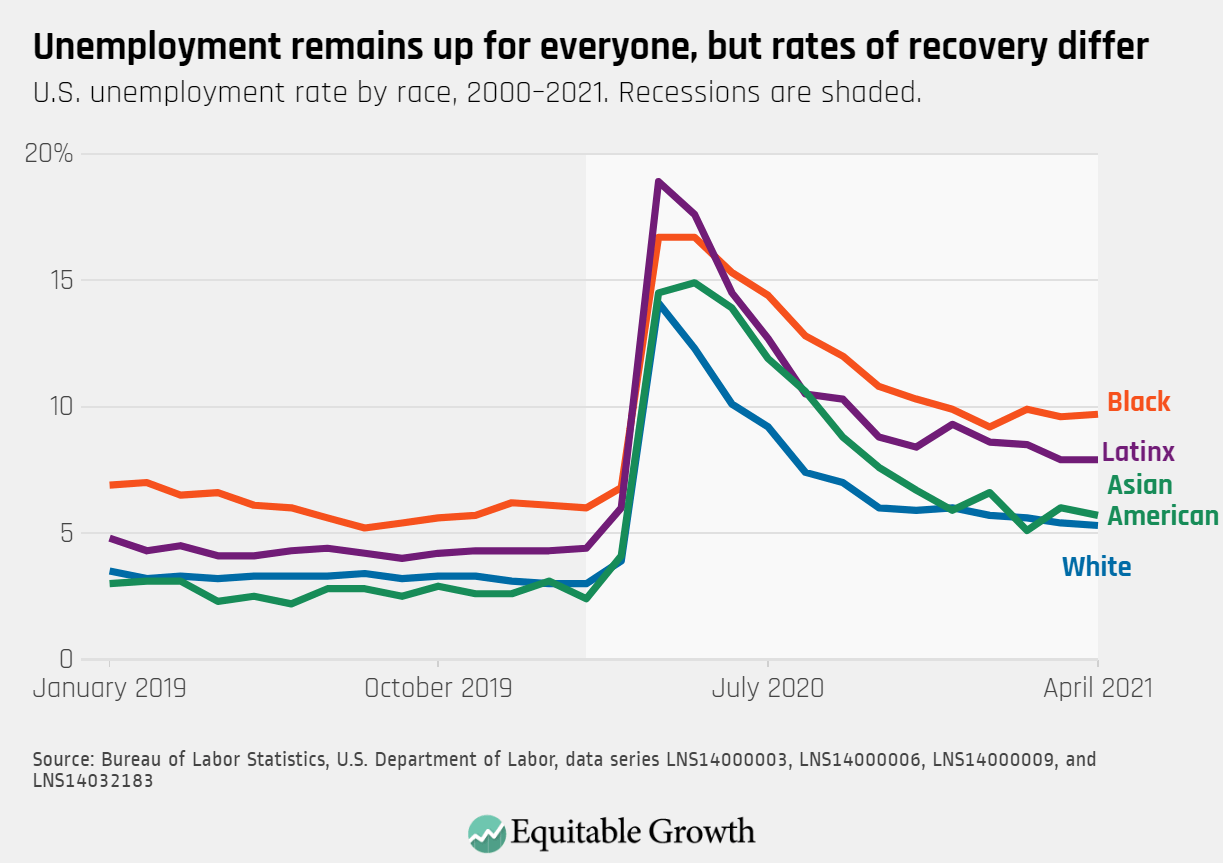

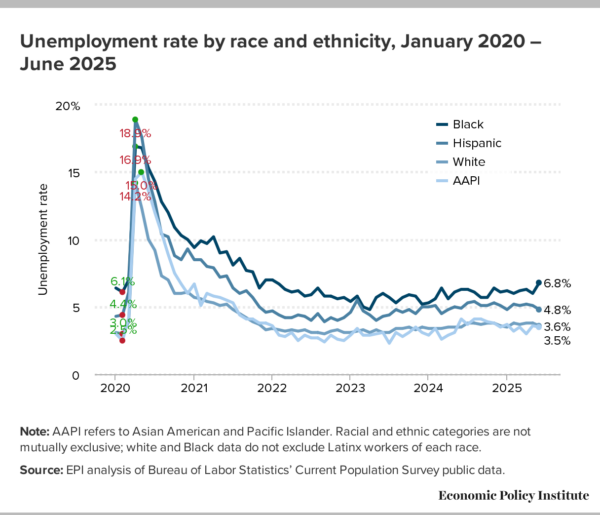

Workers of color, and Black workers in particular, are especially likely to experience displacement

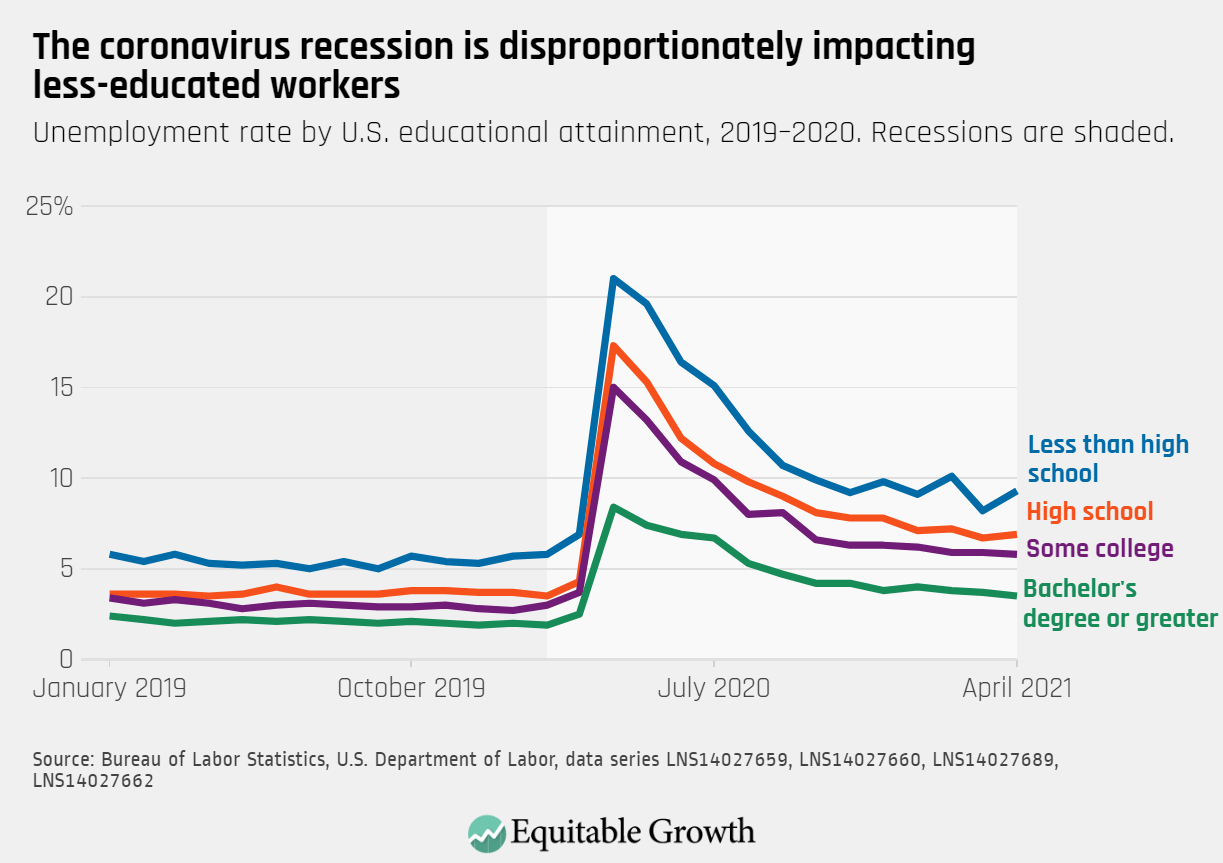

Research stretching back decades demonstrates that workers of color are more likely to experience job displacement than their White counterparts. There is evidence, for instance, that Black workers are the first to be fired as the U.S. economy contracts—a finding that holds even when accounting for characteristics such as education, occupation, and industry. This evidence underscores the importance of strengthening the enforcement of workplace anti-discrimination laws during economic downturns.

Alarmingly, the Black-White job displacement divide is more severe today than it was in the 1990s. Using data from the Displaced Worker Survey of the Current Population Survey, Elizabeth Wrigley-Field of the University of Minnesota and Nathan Seltzer of the University of Wisconsin-Madison analyze racial disparities in job displacement between 1981 and 2017. They find not only that Black workers were nearly always more likely to be displaced than their White counterparts, but also that sectors in which Black workers are overrepresented and which used to provide a higher degree of job security—especially jobs in the public sector—no longer do. The authors also find that these disparities exist when controlling for education level, meaning that being White reduces the likelihood of displacement as much as having a college degree.

The effects of job displacement and mass layoffs can ripple through the entire U.S. economy

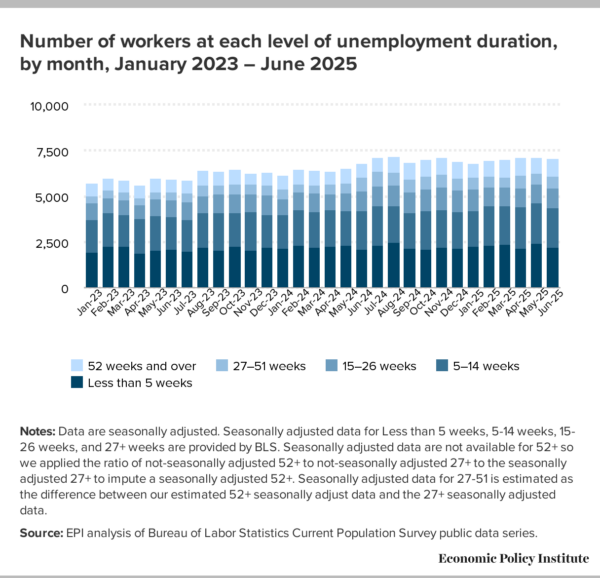

Job displacement hurts not only those who experience it, but could also harm the entire U.S. economy by causing recessions to last longer and be more severe. As noted above, workers who experience a displacement tend to have lower job-finding rates and are more likely to be unemployed for longer periods of time. Research shows, in turn, that high levels of long-term joblessness can suppress overall wage growth and lead to lower economywide employment levels.

In addition, the income volatility associated with job loss threatens the economic security of key consumers in the U.S. economy. The spending of workers who are historically more exposed to job displacement—workers of color, younger workers, and workers without a college degree—is also particularly sensitive to income shocks. As a result, the unequal exposure to displacement and income loss more generally can trigger a feedback loop where important consumers have to cut back their spending dramatically, reducing demand for goods and services and leading to further job losses.

Policies to prevent and mitigate the negative consequences of displacement

Job displacement is a hugely disruptive labor market outcome for U.S. workers. To protect them from negative consequences associated with displacement, policymakers should consider ramping up Short-Time Compensation—a program within the broader Unemployment Insurance system that helps workers avoid displacement by allowing employers to temporarily cut labor costs while keeping workers attached to their jobs. Under Short-Time Compensation, employers can reduce the number of hours of work for a group of workers who, in turn, receive prorated jobless benefits that replace a portion of their lost wages, allowing both workers and employers to withstand a temporary drop in business.

When job displacement happens, income-support programs, such as extended Unemployment Insurance, can give workers the time and economic security they need to find employment that is a good match for their skills and interests. Research by Adriana Kugler and Umberto Muratori at Georgetown University and Ammar Farooq at Uber Technologies Inc. shows that during the Great Recession of 2007–2009, workers who had access to Unemployment Insurance benefits for a greater number of weeks were more likely to experience upward occupational mobility and earn higher reemployment wages. These findings thus point to the need to make jobless benefits accessible for longer and to tie the duration of the Extended Benefits program to improved automatic triggers.

Expanding workers' abilities to organize and join unions may also help reduce some of the harms of job displacement. So-called reduction in force clauses in collective bargaining agreements can help mediate the level of job displacement, as well as provide other supports for workers when job loss is unavoidable, such as requiring employers to rehire the laid-off workers if and when business conditions improve. Proposals to enable wider unionization across the U.S. labor market will help workers on many fronts, including when they may be at risk for losing their jobs.

The central factor across these and other policies to mitigate the harms of job displacement is maintaining employees' attachments to their jobs when at all possible and supporting workers' incomes when job loss is unavoidable to improve their long-term earnings outcomes. Long-term restructuring of the U.S. economy is inevitable and ultimately fosters a robust economy, and ensuring workers are supported through these shifts is essential for ensuring broadly shared growth.

The post The consequences of job displacement for U.S. workers appeared first on Equitable Growth.

-- via my feedly newsfeed